© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Gravesend - Gateway to London

Situated on the Kentish shore of the River Thames opposite Tilbury, Gravesend is one of the main bases of river and Channel pilots, of Customs and immigration officers and of the Port of London Sanitary Authority

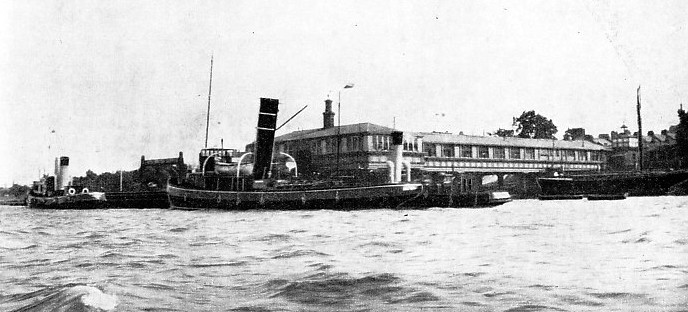

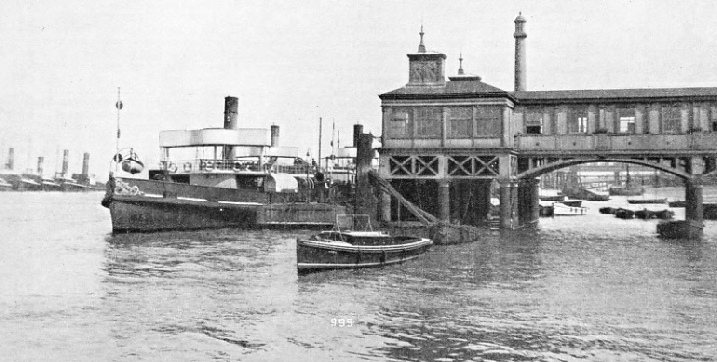

ROYAL TERRACE PIER at Gravesend, on the River Thames. The building at the end houses the two sections of the Trinity House Pilot Service. The river pilots have the section whose windows face downstream, so that they can watch for the incoming ships which they are to take over from the sea pilots. The Channel pilots have the section facing upstream.

IN every port there is one point of particular interest, generally close to the entrance where the whole of the shipping and traffic is to be seen from a convenient spot. In the Port of London this point is Gravesend, in Kent. Every ship entering or leaving the port has to pass it except the spirit tankers, which are not allowed above Mucking, lower down the river. Gravesend is the true gateway, with its little promenade named after General Gordon — a great figure in the town — and the Royal Terrace Pier. All the time the keepers of the gate are busy with their respective tasks, so that there is always some activity in the Reach to catch the eye of the interested observer.

It has been so from time immemorial. When the capital lived in terror of Viking raids Gravesend was one of the keys of the defence. Permanent works were erected there, although the width of the river prevented their being particularly successful, with the weapons then in use, in checking the long ships. The name of Gravesend shows its importance in Saxon days. It had nothing to do with burying people, as the local legends would have it, but it was the headquarters of the Graave — a title which is still to be found in Germany as Graf (“Count”) — who was particularly charged with the defence of London.

At a later date the Reach, and particularly the town, were fortified by King Henry VIII when he was wondering how the Pope would reply to his defiance. In those days Gravesend was still regarded as the gateway in peace as well as in war. The town was the end of the Long Ferry from London, which was used by every wise traveller in preference to the dangerous roads over the heaths and commons.

When there was an Ambassador to be met, a visiting Sovereign to be received, or a Royal bride to be welcomed into the country, it was almost invariably at Gravesend that the ceremony took place. Sometimes it would be graced by Royalty, but more often the Lord Mayor of London, in the beautiful State Barge of the Corporation, with an escort of barges, nearly as elaborate, owned by private individuals and by the great City Companies, would meet the visitor’s ship at Gravesend and, after due ceremony, would proceed up to London in a brilliant and generally noisy procession. But all this is past. At an early date Gravesend was made the gateway for customs purposes. There were many lonely stretches of the river on the way to London where goods could be slipped ashore and carried into the capital by back ways before the ship’s cargo was checked.

It was a great advantage to the King to have his valuation made as far downstream as possible. By the time the ship had reached the capital so many of his loving subjects had taken advantage of their rights of perquisite that the cargo would have been appreciably lightened. All ships leaving the river had to get their clearance at Gravesend.

To warn the Customs that a ship was coming downstream, the sentry on the ramparts of the fort would discharge his musket, the unfortunate shipmaster being charged an exorbitant sum to pay for the powder. Hotels sprang up in the town to accommodate the passengers of the stately East Indiamen, anchored in the Reach waiting for a fair wind. These passengers refused to embark until the last moment, and the ships’ pursers meanwhile topped up the supply of provisions, not forgetting the asparagus for which the town was famous. At a later date the sailing emigrant ships would also be detained for long periods off the town, and all the early entries in the baptismal register of the quaint little Sailors’ Church on the shore of Bawley Bay are concerned with the passengers of these ships. Finally, there were the crimps to supply seamen in place of those who had deserted with their month’s advance.

Gravesend is as important a gateway as ever it was. Its keepers are as busy as, and far more efficient than, their more picturesque forbears. They are all occupied keeping in steady movement the traffic of the busiest port in the world — an essential consideration in view of its enormous volume — and they do that with a complete absence of fuss and often no uniform.

The incoming ship in particular demands much attention so that no time or money shall be wasted, and Gravesend is situated in the most convenient spot to give her this attention. Unless she belongs to one of the classes which have been specially exempted, the incoming vessel has taken a pilot either off Dungeness (Kent) or at the Sunk Lightship off Harwich (Essex). By the time the pilot has brought her safely up to Gravesend he has already done a hard day’s work. So off the Royal Terrace Pier, which is owned by the Trinity House pilots themselves and not by Trinity House, he hands over his charge to the river pilot, who takes her on to the entrance of the dock to which she is bound, or alongside the wharf where she is to discharge her cargo.

Precisely the same routine holds when the ship is leaving the port. Her river pilot brings her down as far as Gravesend, where he disembarks in the pilot launch, or in the attendant tug if it happens to be more convenient, and hands over to the Channel pilot, who takes her through the dangers of the estuary. If she is bound north, he generally leaves her off the Sunk Lightship. There he transfers into the cruising cutter and waits for a ship bound back to Gravesend. Ships going to the southward discharge their pilots to the shore, generally by motor boat, and the pilots then find their way back to Gravesend by train or by road.

The incoming ship also receives immediate attention from the Customs service, whether her people desire it or not. There was some sort of a Customs organization at Gravesend long before it was contemplated at most other ports, but for many years it was housed in a local tavern. It was not until Tudor days that Gravesend had to give place to the Custom House in London, where all the principal business was transacted; Gravesend, however, still had plenty to do. At the end of the eighteenth century the present fine Custom House was built, overlooking the river at the eastern end of the town.

In those days the building was not only a Customs office but also more or less a barracks for a large staff of various grades. Its principal business was to take precautions against the surreptitious landing of goods, so that as soon as a ship arrived at Gravesend from abroad a Customs officer, with his hammock and bedding, boarded her and remained on board until she was leaving the river.

Unhurried Efficiency

Nowadays everything is changed. By far the greater part of the Customs officer’s activities are centred round the operations of discharging the ship, for most items in her manifest will be subject to duty in some form or another. The officers are therefore more or less concentrated on the discharging quays and in the docks, where they examine with an expert eye everything coming out of the ship.

But there are other branches of the Customs work. One is concerned with the passenger trade. As soon as a ship with passengers on board gets alongside the stage at Tilbury, on the Essex side of the river, there are a number of officers from the Gravesend station waiting to examine their baggage. The quietly efficient manner in which they perform this task, creating no fuss but letting through little that is of any importance, is the admiration of every observer of Customs procedure in some other countries.

But there are other branches of the Customs work. One is concerned with the passenger trade. As soon as a ship with passengers on board gets alongside the stage at Tilbury, on the Essex side of the river, there are a number of officers from the Gravesend station waiting to examine their baggage. The quietly efficient manner in which they perform this task, creating no fuss but letting through little that is of any importance, is the admiration of every observer of Customs procedure in some other countries.

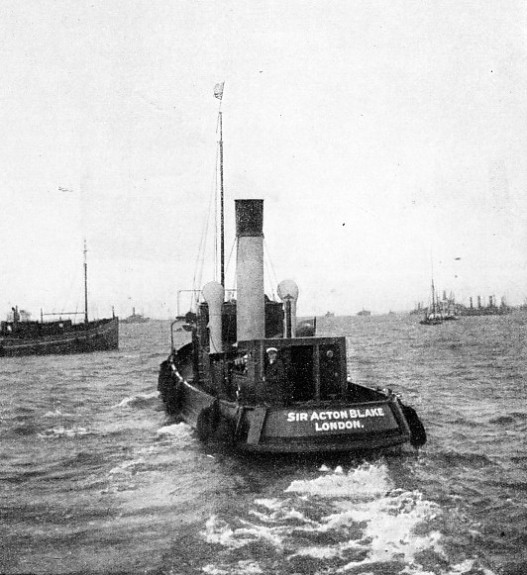

A GRAVESEND PILOT LAUNCH putting off from the Pilot Station. The pilot, who is standing on the after deck of the Sir Acton Blake, is being taken to an outgoing steamer to conduct her clear of the shoals in the Estuary.

As smuggling is regarded as such good fun by many people, and is deeply ingrained into the character of some who are otherwise strictly honest, the officers on this duty have to be wide awake.

They make a surprising number of captures, concentrating their attention on the things that matter most, especially concerning duties which are imposed to provide employment rather than to raise revenue, and with checking any unhealthy idea that the department is easily hoodwinked. But, as with every other official connected with the port, they aim at keeping the wheels running steadily and at delaying the legitimate business of the port, including the boat trains, as little as possible.

Perhaps the most romantic part of the Customs service is the rummaging. The rummage crews, normally consisting of one preventive officer and three assistant preventive officers, board a ship at any convenient point, but generally at Gravesend, where the captain receives from the launch his various papers. In exceptionally big or specially suspect ships a “massed rummage”, with two or three crews, is sometimes ordered, but even the ordinary four men can do wonders.

Considering how complex is the interior arrangement of a modern ship, it is remarkable that, on the passage between Gravesend and the docks, four men can disinter small deposits of contraband from all sorts of ingenious hiding-

Closely allied to the Customs is the work of the Immigration Department, or Aliens Service. This important section of the Home Office works with a special division of Scotland Yard. Before the war of 1914-

Hurried measures were therefore taken to raise a proper force of immigration officers, and volunteers were accepted from Civil Servants among the various departments. These officers settled down to their work immediately and laid a solid foundation on which the service has since been built up. After the Armistice the whole department was put on a peace-

The immigration officers wear no uniform, but they board incoming ships and quietly get through the business of examining hundreds of passports and checking the identity of the seamen, with extraordinary speed and efficiency. They never forget that passports can be forged, the concessions to excursion passengers from the Continent can be abused and criminals and other undesirables can slip into the country disguised as foreign seamen whose movements, while their ship is in the Port of London, are restricted as little as possible.

The immigration officers wear no uniform, but they board incoming ships and quietly get through the business of examining hundreds of passports and checking the identity of the seamen, with extraordinary speed and efficiency. They never forget that passports can be forged, the concessions to excursion passengers from the Continent can be abused and criminals and other undesirables can slip into the country disguised as foreign seamen whose movements, while their ship is in the Port of London, are restricted as little as possible.

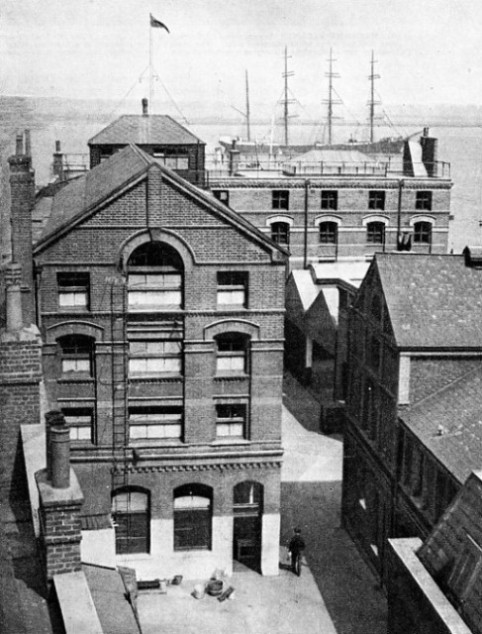

GRAVESEND SEA SCHOOL offers training to boys who wish to become seamen in the Mercantile Marine. Boys enter between the ages of sixteen and eighteen. In the background is the Olivebank, a steel four-

The Port Sanitary Authority is also centred largely on Gravesend. This service is particularly interesting because it is the last hold on the river to be retained by the Corporation of the City of London. The Corporation became absolute from London to the sea when Richard I was so short of money for his Crusade that he would sell any right for ready cash. For centuries it did its work well, but when the port began to develop so rapidly it soon grew out of the Corporation’s control and section after section had to be allowed to pass under other authority.

The health of the port and of the capital remains the Corporation’s particular care. Here is another service which does splendid work without the general public being aware of its existence. At Denton, at the east end of Gravesend, there is a big isolation hospital on the river bank for the accommodation of those who have contracted or are suspected of infectious disease. Here also bedding, clothing and other property which has been in contact with infection are scientifically treated. Off the Gordon Promenade there is moored the hulk Hygeia, the fourth of that name at the present time, where a doctor who is a specialist in his work is always on duty, with a motor launch alongside ready to take him to any ship which requires his services.

The service under the control of the Corporation goes back to the beginning of quarantine, which takes its name from the primitive idea of isolating the ship and everybody in her, including the pilot, for forty (from the Italian quaranta) days. Apart from that quarantine, about the only thing that was done when a ship was suspected — generally on good authority — of bringing plague into the country was to take her downstream and scuttle her with all her cargo on board, naturally raising a shoal of sand round the wreck. Considering how the plagues which periodically descended on the country — the Black Death, the Great Plague and many others — were undoubtedly imported by shipping, we can scarcely blame the authorities of those days for panic legislation.

With the co-

War Against Plague Carriers

Every one of these ships is boarded by the doctor, who, by long practice, can detect what he is looking for in a moment although his examination appears to the outsider to be casual. Those suffering from or suspected of infectious disease are sent ashore, and precautions are taken according to the risk. The doctors must not only be experts in detection but must also be wily enough to circumvent the inevitable efforts of the Asiatic to conceal any illness from which he may be suffering. Until the doctor is satisfied the Customs will not grant pratique (licence to communicate with the shore) and nobody may leave the ship.

The detection of plague is only one of the doctor’s duties; he thinks just as much of prevention. He and his staff are therefore in control of the campaign for the suppression of rats on shipboard by the use of poison gas or other means. The “deratisation process”, as it is officially named, is a regular one and the body of every rat killed in that way, or caught at sea, is carefully examined to see whether it is a plague carrier. Other vermin are similarly dealt with.

Working with the doctors are a number of sanitary inspectors, certificated master mariners who know the sea thoroughly and who have also passed stiff examinations in sanitary work. They not only assist the doctors in various ways, but they also inspect the ships to see that they are kept in a sanitary condition. In maritime law this covers a great deal. Lack of ventilation, lack of heating, broken portholes, leaky decks and a hundred other things may make a ship insanitary and may produce a demand from the Port of London Sanitary Authority that matters must be rectified. Its officials also keep a sharp look-

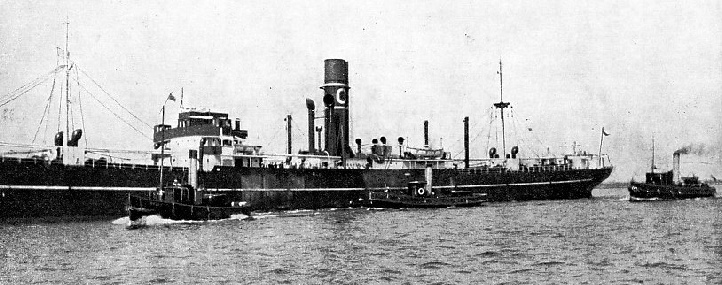

AN INCOMING STEAMER changes pilots off Gravesend. The cutter on the left has just put the river pilot on board the Goolistan 5,851 tons gross, and has taken off the Channel pilot. The launch going alongside is a Customs vessel handing the captain the necessary papers; the second one on the right is carrying a rummage crew. The Goolistan is a tramp steamer owned by the Hindustan Steam Shipping Co., Ltd.

The Port of London Authority, which controls the Thames from Teddington Lock to beyond the Nore (see the chapter “London’s Link With The Sea”), has its headquarters in Trinity Square, close to the Tower of London, but the headquarters of the Lower River district are at Gravesend. Here are a harbourmaster, his assistants and the various departments for the control and improvement of the river. Many of the essential services, ensuring the safety and rapid transit of shipping, are based on Gravesend.

First there is the Harbour Service, with the Harbourmaster and his assistants, as well as several inspectors, constantly patrolling the river to make sure that the fairway is kept clear, that there is no abuse of the facilities, and that no vessel helps herself to an advantage to the detriment of the other users of the port. The whole district is regularly patrolled and everything likely to influence shipping is carefully noted and rectified.

Working in co-

First-

Gravesend is also the home of one important section of the tug services of London, those which handle the big ships and help them in and out of dock. In the old days the main business of the Gravesend tugs was to go down Channel seeking for sailing ships to tow to London and to help them out to sea again. Now that sailing ships have almost disappeared, the increasing size of steamers makes it necessary to employ tugs — one, two or three as the size of the vessel and the difficulty of the job may dictate. Between tides there are generally numbers of these powerful tugs, ranging from 750 to 1,100 indicated horse-

Watermen work from Gravesend in motor boats, or in pulling wherries whose design has remained unaltered for many years. They land the pilots from incoming ships, offer helmsmen who are experienced in every turn of the river, handle passengers to and from ships in the stream, obtain provisions or anything that is wanted in the town, maintain communication with the agents and owners, carry off mooring ropes, and do a thousand and one jobs which crop up in a busy port.

Finally, Gravesend is a first-

TILBURY-

You can read more on “His Majesty’s Customs Service”, “London’s Link With The Sea” and

“Pilots and Their Work” on this website.