© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Life in the East Indiamen

Famous though the vessels were, surprisingly little comfort could be obtained on a voyage to India or China in an East Indiaman, despite the exceptionally high prices paid for a passage

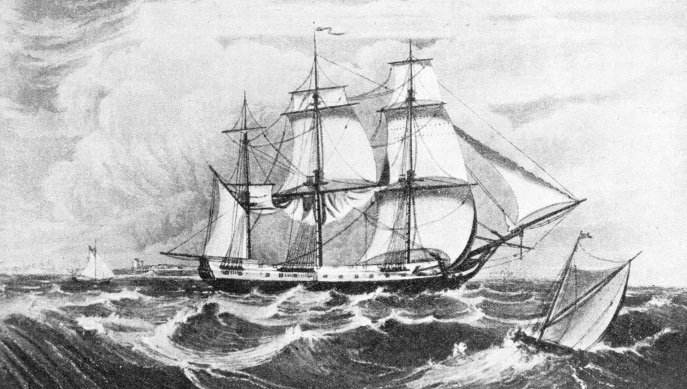

BUILT IN 1790 at Deptford, on the River Thames, the True Briton was one of the famous vessels of the East India Company. She was of 1,209 tons by her builder’s measurement. Losses to East Indiamen were appallingly heavy and the True Briton did not have a long life. On a voyage to Bombay and China in 1809 she disappeared at sea without a trace.

IN Joseph Sedley, Collector, of Boggley Wollah, Thackeray drew a type of person who had become notorious as a nabob. The word implied contempt, and related especially to English merchants who had made fortunes in India and returned to spend them in their own country.

The nabob and many other persons of romantic interest were essentially the products of the famous old East India Company, the most powerful body of its kind that ever existed. “John Company” was incorporated in 1600. In 1858 it ceased to exist, the government of India having passed to the Crown. During those two and a half centuries the Company had almost incredible power and prosperity in India and China. It had its own army and fleet, and to be in the upper ranks of its service was to be assured of a fortune quickly made, though great risks to health and life had to be taken. The ships of the Company, known as East Indiamen, had and have a special fascination, for they were a combination of trader, passenger carrier and man-

In one round voyage he could reckon on making from £3,000 to £5,000, but sometimes the total return was £10,000 or even more. One commander made £30,000 on the round voyage from London to India and China and back. The other officers shared proportionately in a voyage. Even with these amazing profits some of the commanders and other officers were not satisfied and they smuggled and traded illicitly to make further gain. At her zenith the Indiaman was a wonderful creation. One of the finest of the ships was the Earl of Balcarres, of 1,417 tons.

In addition to the commander himself, the crew included six mates, a surgeon and an assistant, six midshipmen, purser, boatswain, gunner, carpenter, sailmaker, master-

Life in the Indiamen was such that no one could look forward to it with pleasure. Even to the most fortunate traveller there were the serious drawbacks of limited space, monotonous voyaging, and the ever-

Passengers of lesser importance were cramped to a degree that is hard to realize, and soldiers, women and children were simply herded together. Many of the cabins were makeshift affairs with canvas sides that could be quickly removed in an emergency, as when fighting an enemy. Then the whole of the decks would be cleared for action.

Indiamen, coveted prizes to national enemies and pirates and other sea wolves, voyaged in convoys in times of danger. They were equal to men-

Hall was in one of the men-

Foretaste of Modern Luxury

The Indiamen were “huge China ships” which in a calm drifted about “ore like logs of wood than anything else.” The unfortunate bad sailers were hourly execrated in every note of the gamut, Hall added, and sometimes the progress of “one haystack of a vessel” was so slow that a fast-

Bad though things were in the daytime they were worse at night, when Indiamen grew to resemble phantom ships, scarcely moving. All lights were out and strict silence was ordered, these precautions being designed to hide a ship or fleet, from an enemy’s attention. Lights at best were feeble, being only oil lamps or candles, but risks were not taken unnecessarily.

Food in the Indiamen was abundant but hard to keep in a fresh state. The principal meal of the day, dinner, was not later than 2pm, and it was made to last as long as possible. There was never lack of spirits and wine, both of which would have been at times gladly exchanged for drinkable water. Scurvy was a great enemy and accounted for many lives.

In 1815 Captain Hall accompanied a convoy of homeward-

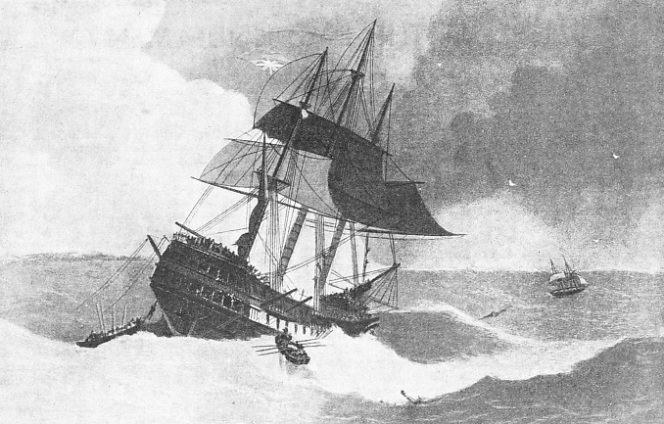

A MEMORABLE DISASTER TO AN EAST INDIAMAN. The story of the burning of the Kent, 1,350 tons, in the Bay of Biscay, is fully described in the chapter “Menace of Fire at Sea”. The Kent was in dire straits when the brig Cambria came to her assistance. With great difficulty and at great risk the majority of the Kent’s people were rescued, although more than eighty perished.

The centre of all this hospitality and joviality was the most famous feature in the Indiamen -

The losses of Indiamen through fire, foe and shipwreck were appallingly heavy. Memorable were the disasters. The Abergavenny, for instance, was lost off Portland Bill in February 1805, and more than 300 of her people perished. The Halsewell, too, was wrecked in January 1786 on the Dorsetshire coast, and 386 were lost, including more than seventy lascars.

As a contrast to Hall’s pleasant picture is the story of a mutiny in an Indiaman at a time when these ships had reached their greatest development and it might have been supposed that their crews had got beyond tyranny and wrongdoing. But the brutal spirit of Bligh of the Bounty survived and the lash was still as freely given as on board a man-

During the voyage the captain, Joseph Dudman, was dissatisfied with the conduct of these seamen. His version was that, words having passed between officers and the prisoners, he heard one of the men, named Larry, say something which made him rebuke that seaman. Larry was ordered to be silent, but refused, whereupon the captain stopped his grog. The insolence continuing, he put Larry in irons. Upon this the other prisoners demanded his release and refused to allow a court of inquiry to be held upon him.

The captain in cross-

“Riotous Assembly and Assault”

The captain had also caused three men to be flogged for breaking into a Chinaman’s house and stealing liquor from it. The Chinaman came on board and picked out the men. The captain did not ask them for a defence, “being satisfied that they could have offered none”. He took the Chinaman’s unsupported word as proof of the men’s guilt.

What the jury thought of the “mutiny” was shown by their verdict -

Such happenings as this showed the worthlessness of some of the Company’s regulations. Commanders were strictly enjoined to be humane and attentive to their men. Divine service was insisted upon as a regular practice, yet on the day the poor lad was lost overboard the log recorded that the weather was so bad that divine service could not be performed. Such worship was a mere travesty of religion.

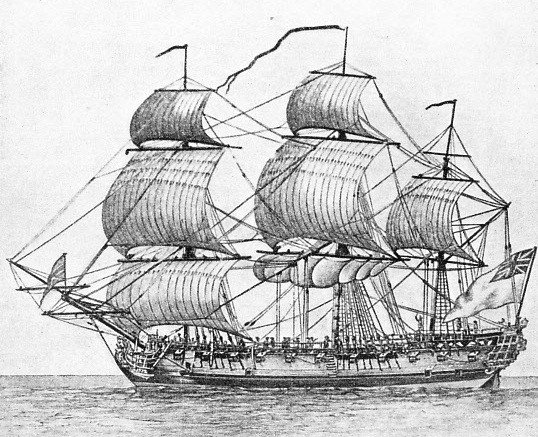

AN EAST INDIAMAN of the type described in this chapter was the Falmouth, launched at Blackwall, on the River Thames, in 1752. She took two years to build. Her length on the keel was 108 ft 9-

In the Indiamen there was neither privacy nor freedom of movement. In a crowded ship there might be and often were months of misery and suffering. An enormous crew, passengers, troops, women and children -

Neither the author’s nor the ship’s name is given, but the vessel was of the usual type for an Indiaman of the period, a famous example being the Falmouth, launched at Blackwall in 1752, after two years had been spent in her construction. She was 108 ft 9-

On July 30, 1746, the author of the narrative joined the ship at Gravesend and was “agreeably entertained” to see a great number of persons on board and the vast preparations and quantities of provisions necessary for so long a voyage. Next day several young people joined, under engagement in the Company’s service for at least five years.

Gravesend was left on August 2, and six days later the ship anchored off Portsmouth. On August 10 treasure was taken on board from Portsmouth and a horse was shipped. More fresh provisions were taken and then the ship made the best of her way to Plymouth, anchoring on August 29 in Cawsand Bay. Not caring to break in upon their stores they sent the longboat ashore for fresh water. They were also supplied with plenty of bread and fish in small boats, which were rowed by “a parcel of the stoutest and most masculine women I ever saw”.

Drastic Treatment for Scurvy

Two days after having left the anchorage, the people on board, including a number of soldiers, were put on an allowance of 5 lb of biscuit a week. On August 26, when there was a “very swelling sea”, each man was limited to two quarts of beer daily. The Indiaman had left with a convoy, and this she parted from on August 27, making her way to St. Helena, where she was to deliver stores.

As the island was reached numbers of birds flocked to the ship and some of them built their nests in the haybags which were carried on the gunwales for use by the horse. The hot weather made it necessary to use the water with the greatest economy, and even then it was little enough to quench thirst. An awning was put over the quarterdeck, to keep off the scorching heat of the sun.

Signs of the horrible and dreaded scurvy were shown by several of the young people on board, and they were ordered to take more exercise, which was then considered the best remedy for that ailment.

Excitement arose from many petty thefts by the soldiers. Daily one or two of them were tied to the shrouds and flogged, but the thefts continued, for, the officer declared, “these wretches who go as soldiers in the Company’s service are for the most part the scum of the three kingdoms, and generally go to India to screen themselves from justice at home”. The soldiers were lazy and inactive, and complained of scurvy, a complaint which was treated drastically and promptly. The men, to prevent infection, were brought up on deck, put into a large vessel of hot water and vigorously brushed with scrubbing-

CHARTERED TO THE EAST INDIA COMPANY, the Macqueen remained in this service for about thirteen years. Nearly all the East Indiamen were chartered to the Company and their owners were known as the ships’ “husbands”. The Macqueen, a vessel of 1,333 tons, was built at Rochester, Kent, in 1821. Her owner was John Campbell, of London.

A week before Christmas the cooper was employed to rebuild the water casks, which for the sake of room had been knocked into staves as soon as they were empty. Many casks of salted pork, which was found to be too rotten to eat, were thrown overboard. It was with delight indeed, therefore, that on Christmas Eve, three months from the start of the voyage, St. Helena was reached, giving a longed-

On Christmas Day twenty-

Since they had left England the ship’s people had lived on salt provisions, some of which were “stinking and almost rotten”, so that fresh beef and plenty of greens made most acceptable and necessary refreshment to all on board. The biscuit had turned mouldy, and on New Year’s Day it was sent ashore, where the ship’s baker baked it over again. Nor was the horse forgotten. A boat was sent ashore to bring a supply of new hay for him.

After a stay of twenty days the ship left St. Helena for Batavia and China. Eleven weeks later land was again seen, “and our water stinking, we rejoiced at the prospect of getting fresh provisions”.

In the Straits of Sundra, Java, the weather was fair and sultry on April 7. In the night, however, after a violent rainstorm, the heat instantly changed to a chilling cold, a condition of things which was intolerable, as the people wore only shirts, trousers and shoes.

Letters Placed in Bottles

The pinnace was sent shore and returned with a bottle which had been found on a conspicuous branch of a tree at Java Head. The bottle contained letters giving an account of the taking of Madras by the French. This custom of placing letters in bottles at places where Europeans were likely to call was so common that every vessel putting in looked for and expected to find letters.

A Malay-

In Batavia Roads there were unexpected developments. The Indiaman found nine Dutch ships, several Chinese junks and the Company’s ship Dragon, all at anchor. They heard that a squadron of French men-

The voyage to Banjar, which was to have been signalized by the presentation of the horse to the Sultan was now abandoned.

There was still a great deal of sailing and trading to be done before the Indiaman left the China Seas for home. There was much heavy weather and consequent hardship, and as the weeks slowly passed scurvy broke out. There were many deaths on board, and it was an undermanned and enfeebled Indiaman which finally reached England, having covered a distance considerably exceeding the circumference of the world.

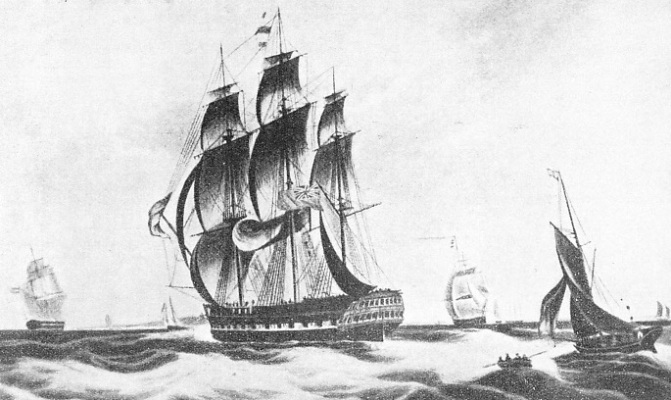

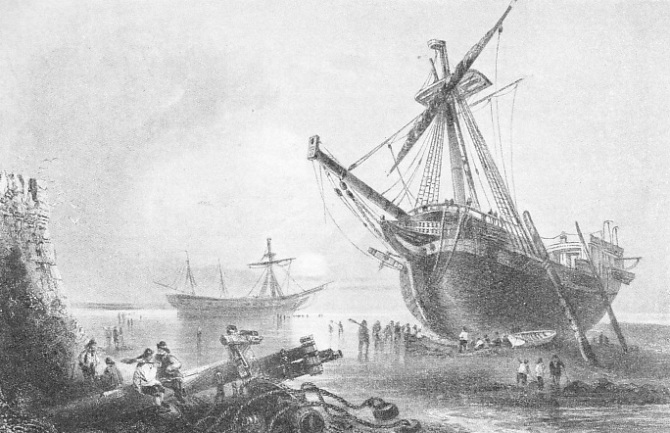

ASHORE NEAR MARGATE, KENT. This illustration of the Westminster and the Claudine appeared in Sharpe’s London Magazine of 1847. The vessels were East Indiamen of the largest class. To escape loss in a gale, the pilot drove them ashore “at the most favourable place”. Both vessels were got off and resumed their stations in the India trade.

You can read more on “The Glory is Departed”, “Handling the Sailing Ship” and “The Menace of Fire at Sea” on this website.