© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

The Menace of Fire at Sea

One of the most dreaded of all the dangers to which a ship at sea may be subjected is fire. Gradually, however, the imposition of stricter regulations and the application of many protective and preventive devices have almost eliminated the risk of a serious fire in a modern vessel

A PASSENGER STEAMER ABLAZE in the English Channel, with a fire-

THE chief dread of every old-

There are many reasons for this improvement, which is of comparatively recent date. Firstly, the original risk of an outbreak has been greatly reduced. Secondly, the means of detecting an outbreak at once, and the organization to tackle it without delay, have been almost perfected. Thirdly, modern ships have been designed and built to isolate an outbreak to a remarkable degree. Fourthly, there are innumerable appliances to overcome any outbreak that might occur; and fifthly, wireless telegraphy can almost invariably call help without delay.

The better and more expensive the ship, the better she is equipped on all counts, and there is therefore infinitely less danger of fire in a passenger liner than there is in a cargo vessel. When a disaster has occurred within the last few years the subsequent judicial probing of the circumstances has almost invariably proved that one or more factors of safety have been neglected and that somebody is to blame.

Things were much different in the old days, and a wooden sailing ship, carrying an inflammable cargo and a large number of passengers, was open to terrible possibilities. There are many instances of such ships being burned at sea, and still more of their disappearing without a trace, although fire may well have been the reason. The disaster to the East Indiaman Kent, in 1825, is well remembered, perhaps because there were many survivors to tell the full story, in spite of the death roll of over eighty.

The Kent, of 1,350 tons, was on her maiden voyage. She was one of the finest ships in the service of the East India Company, and her crew of 148 was as fine as could be found afloat, run on naval discipline without the harshness of naval methods. In addition, she had nearly 500 passengers, consisting principally of the officers and men of the 31st Regiment of Foot, with the proportion of wives and children who went with the regiment on foreign service.

A full gale began to blow, and finally Captain Cobb had everything possible struck aloft and lay hove-

He was able to report, and the first concern of Captain Cobb and the senior military officers was to prevent any rumour of the disaster spreading to the women and children. The big, well-

to prevent any air getting in. Wet hammocks were used for beating the flames out, and a chain of buckets reinforced the pumps.

Despite all these efforts, the thin wisp of light-

The only way to overcome that outbreak was to admit large quantities of water, and this was done so hurriedly that some soldiers in the sick bay, a woman and several children, who were berthed low down in the ship, were drowned before they could be got away, and the sickening fumes suffocated several others. The fire was checked — for the moment, at least — but the ship was in danger of foundering through the water that had been admitted. The sea was still running high, and the motion of the ship had changed to sickening lurches. The hours of the Kent were numbered and, as with most ships of her day, she was not equipped with nearly enough boats to accommodate all her people.

Suddenly the lookout reported a sail on the lee bow and a small brig was made out, snugged down but still making heavy weather of the gale. Guns and rockets were fired but the brig seemed to take no notice. Suddenly she altered course, set all the canvas possible and came round alongside the Kent. The brig was the Cambria, Captain Cook, bound for Vera Cruz. In the howling of the gale the rockets and the signal guns had not been heard, but a good lookout had sighted the clouds of black smoke which was coming through the hatches again.

Powder and Loaded Guns

First of all the women and children were got away, not without the gravest risk of the boat getting entangled in the wreckage which was slamming alongside. It was a perilous run to the Cambria, which lay some distance off for reasons of elementary prudence. For one thing the Kent’s magazines contained a large quantity of powder, and for another the guns were loaded and would certainly go off in succession as the heat reached them.

Under the fourth mate of the Kent the boat made the passage in safety and all the women and children were thus safely transferred from the Kent to the Cambria. The sea was steadily rising. Many were drowned, but the work of rescue went on steadily. Rafts were built and the soldiers followed their womenfolk to safety. Finally the Kent took her last plunge, blazing from stem to stern, when nearly every one of her passengers and crew was out of her.

Such is a historical instance of the dangers of fire at sea in the days of wooden sailing ships. These disasters were all the more catastrophic because the precautionary measures taken were elementary and inadequate.

Prevention is proverbially better than cure and the average shipowner, knowing that nothing is worse for his reputation with passengers and shippers than a disaster, is wisely willing to pay a good deal of attention to the first necessity of eliminating, or at least greatly reducing, the risk of an outbreak of fire.

These measures are considered in the original designing of the ship and go on through her construction and her loading and running on every voyage. They may be expensive, and the cost of the precautions against fire may appear startling to the layman, but the outlay is well worth while.

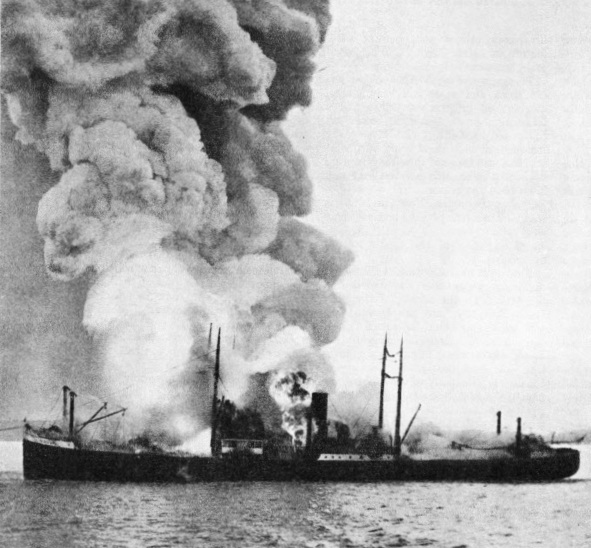

BLAZING FROM STEM TO STERN. A fierce fire was caused by the combustion of the cargo of saltpetre in the Ares at Lisbon, Portugal, in April 1931. Built at Zaandam, Holland, in 1921, the Ares was a vessel of 3,981 tons gross. She had a length of 340 feet, a beam of 48 feet and a depth of 28 ft. 6 in.

One of the most important factors is the ability to control heat. Heat is sure to be generated in the boiler-

Coal, whether it is in the bunkers or carried as cargo, is particularly susceptible to spontaneous combustion, especially certain grades such as those which are shipped in the Baltic ports. The state of this coal has to be carefully examined when it is shipped, and the greatest care has to be taken when it is on board. Fresh bunker coal shot on top of old is another frequent cause of trouble.

Hay, fodder and jute are all liable to spontaneous combustion if they are shipped wet, and special precautions have to be taken with nitrates, certain chemical products, sulphur, matches and a hundred other things. Many cargoes which are liable to spontaneous combustion are carried on deck only, so that they can be carefully watched all through the voyage.

The use of fireproof material in the first place is a prime preventive factor, and despite the demand for elaborate decoration there are few owners who will consent to anything inflammable being worked into the structure of the ship. Steel and chemically treated wood, even for the furniture, have replaced the ordinary wood which fed so many fires in the old days.

Everybody has to co-

Emigrants’ Carelessness

In the old days when thousands of ignorant emigrants were packed into a sailing ship, their recklessness with regard to the fire risk was astounding. Orders for the elimination of the danger were always made and notices pasted up, but half the emigrants could not read and the other half did just as they thought fit. There is no doubt that this was the cause of many fine ships being lost without a trace.

In the fire in the Ocean Monarch in 1848, although nearly half the ship’s company was saved, the death roll was 178, and the disaster occurred off the coast of North Wales, where help might have been expected.

The Ocean Monarch was one of the magnificent clipper-

Before they left the Mersey, the captain had warned his passengers carefully against smoking below decks, where every available inch was packed with emigrants, their straw-

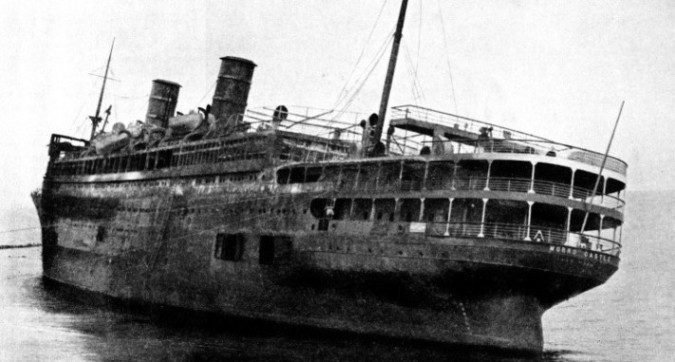

GUTTED BY FIRE AND BEACHED at Asbury Park, New Jersey. The Morro Castle was the victim of a tragic fire in September 1934. She was a turbo-

Water was pumped through the scuttle and through holes cut in the deck, but the fire-

Help was soon forthcoming, but the panic cost many lives, although a number of people were saved by various vessels, conspicuous among which was the yacht Queen of the Ocean, returning from Beaumaris (Anglesey) Regatta. Had it not been for the attitude of the passengers, their resentment of discipline, their stupid lack of the most elementary thought and their panic in face of danger, the Ocean Monarch disaster would never have occurred.

With the modern habit of smoking everywhere and at all times, the fire risk is always present and has to be guarded against. It was a simpler matter in the days of the old rigged warships when fire was the greatest terror. Smoking was then strictly prohibited between decks and the only place in which it could be indulged legally was on the forecastle head, where the smokers had to gather round a huge tub of water over which they had to keep the bowls of their pipes. A Royal Marine with fixed bayonet was there to make sure that the regulation was obeyed.

Because of the tankers’ special cargo the regulations to-

Automatic Sprinklers

Such are the principal precautions taken against an outbreak of fire occurring at all, but if it does, the next thing is to detect it at once. Celerity is the very essence of fire-

Some ships are fitted with air ducts which extract the air from every enclosed part of the ship and discharge it in the chart room under the nose of the officer on watch. Considering the size of a modern ship it is wonderful how accurate this means can be. Many a stowaway has found a search-

Another method is by the use of selenium cell sensivity. Certain electric alarms are actuated by a rise in temperature, but great care has to be taken that they are not set off by the heat outside the ship when she is passing through the Red Sea or some such particularly hot area.

Recently there has been a much greater tendency for passenger steamers to adopt the sprinkler system. This consists of a number of sprinkler points, distributed throughout the ship, which are not only sensitive to a rise in temperature, but which cause a discharge of a spray of water the moment the heat reaches a certain temperature. This is generally sufficient to quell the beginning of a fire. Immediately a sprinkler comes into action an alarm is automatically sounded on the bridge and an indicator shows in which particular section of the ship the fire has broken out.

Recently there has been a much greater tendency for passenger steamers to adopt the sprinkler system. This consists of a number of sprinkler points, distributed throughout the ship, which are not only sensitive to a rise in temperature, but which cause a discharge of a spray of water the moment the heat reaches a certain temperature. This is generally sufficient to quell the beginning of a fire. Immediately a sprinkler comes into action an alarm is automatically sounded on the bridge and an indicator shows in which particular section of the ship the fire has broken out.

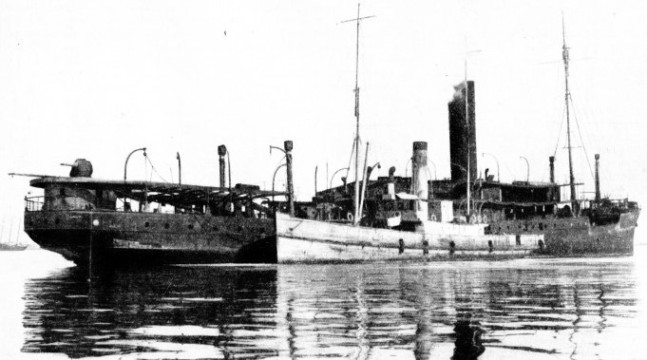

SMOKE POURING FROM THE ILL-

No matter how well the ship is equipped, the wise master insists on a constant patrol, generally by the Master at Arms and one or two picked reliable ratings. It is a matter of great debate whether a regular fire brigade is an advantage. Within recent years some liners have engaged one, with no other duty than the detection and suppression of fire. As a fire is of rare occurrence such a special brigade is liable to suffer from boredom in the long run and its vigilance may decrease, while quartermasters and seamen taking their turn when it happens to be their watch are always comparatively fresh at the game. Sailors brought up from their youth to tackle any emergency that may arise, always make first-

One of the most unfortunate instances of negligence concerning protection from fire occurred off Hell Gate, in New York Harbour, on June 15, 1904. The General Slocum, a popular excursion steamer of 1,013 tons gross, was crowded with passengers when fire broke out in the saloon. There was an immediate panic and the upper deck fell in. The captain managed to beach the vessel, but not before 959 lives had been lost. The scandal was that none of the fire-

The modern ship is carefully designed to isolate any fire that should occur. Below decks the holds are divided by bulkheads which are fireproof as well as watertight, while as far as possible the hatch covers dividing the ’tween decks and holds are made fire-

Alleyways between the passengers’ cabins can easily act as draught tunnels through which the flames are fanned. Nowadays, therefore, the alleyways are carefully broken up, although the method is inconspicuous to the passenger and generally passes unnoticed. Turns in the alleyways and blocks of cabins put athwartships help in this, and fireproof doors, hinged back but ready for instant use, are numerous in the modern passenger ship.

Importance of Wireless

It is necessary not merely to detect and localize an outbreak. It has also to be overcome as quickly as possible and the fire-

Dotted all round the ship are rolled-

Finally, even the worst fire at sea no longer carries the terror of loneliness, for wireless calls for assistance are sent out at once and most countries insist on due precautions being taken to . enable messages to be dispatched no matter where the fire may be. The wireless has rarely failed to bring help to a burning ship in recent years.

Perhaps the greatest safeguard of all is cleanliness, for the risk of a big fire in a ship which is kept really clean everywhere is infinitesimal. There is less liability of an outbreak occurring and infinitely less liability of its spreading to dangerous proportions. The passengers who are apt to sympathize with the sailors because they are constantly kept busy cleaning every part of the ship should remember that this is a great factor in their own safety. They are wise, therefore, to travel in the ships of a company which has the reputation for cleanliness and whose officers are keen enough to insist on maintaining it in all circumstances.

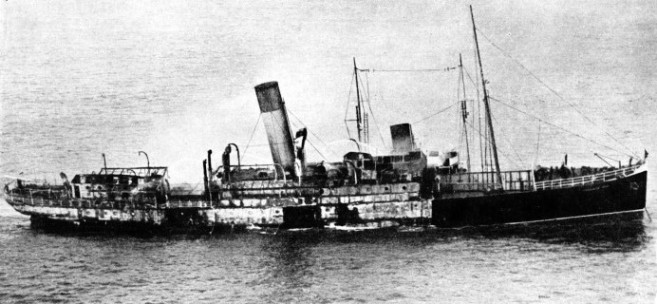

SALVAGE AFTER THE FIRE. The Ophir was a Rotterdam Lloyd liner of 4,726 tons gross, built at Flushing in 1904. During the war of 1914-

You can read more on “Heroism and Disaster at Sea”, “The Menace of the Derelict” and “The Modern Ship’s Wireless” on this website.