© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

The Menace of the Derelict

A tragic sight and a peril to other craft, abandoned sailing ships caused such havoc in the shipping lanes that special measures were taken to rid the sea of them

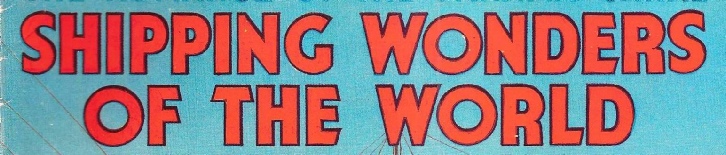

TOWING A DISABLED SHIP INTO PORT. A photograph of the US coastguard cutter Seneca at the work of ridding her territory of abandoned vessels. The Seneca was built in 1908 specially for the purpose of hunting down derelicts. A single-

FEW sailors of to-

The number of modern steamers lost at sea nowadays is negligible compared with the number of the old sailing ships that were lost. Further, steel hulls and heavy machinery almost invariably take steamers straight down to the bottom, and their crews seldom have difficulty in opening the sea cocks if it is necessary to hasten the end. But with the wooden sailing ships it was different. Although the crews who had to abandon them were always expected to take the precaution of setting them on fire, this precaution was not always successful, and the derelicts sometimes drifted for years.

An abandoned sailing ship, floating practically flush with the water and loaded with timber until she was a solid lump, difficult to pick up in the daytime and, of course, unlighted at night, was one of the greatest dangers of the sea. She was regarded with much more dread than the iceberg, for she was just as dangerous to hit and, unlike the iceberg, offered no warning of “blink”, smell or temperature.

The most celebrated of all derelicts is, of course, the Marie Celeste, which was discovered abandoned in the late ‘seventies, Her story has become one of the great mysteries of the sea. Resembling the story of the Marie Celeste in many details is that of the brig Resolven. In 1884 this little vessel, which had sailed to collect stockfish from the fishing schooners on the Grand Banks, was found deserted by a boarding party from HMS Mallard. The sidelights were still burning and there was a fire in the galley. In the cabin there was a bag of gold coin ready to pay the fishermen for their catch.

What had happened to the crew nobody ever knew. There was no question that she had been abandoned in a hurry, but what was the reason and what had become of her boat? The fire in the galley made it obvious that the crew had only just gone, yet the Mallard found no signs of them, although she cruised round for hours in search, nor did she see anything which could explain their hurried departure.

Even more strange was the experience of the American sailing vessel Ellen Austin. In 1881 she found a derelict-

A well-

As the schooner almost certainly went straight to the bottom, she did not worry the other navigators on the Western Ocean, as the derelicts did -

In 1895 there was the instance of the lumber-

The Alma Cummings was reported frequently and was boarded by a boat’s crew from steamers on five occasions, with the idea of destroying her by fire. All they did, however, was to burn her down to the water’s edge, so that she gave even less warning to lookout men. Warships of more than one navy were ordered to seek her out and destroy her. But those were before the days of wireless telegraphy, and the naval men had to wait until the ship which sighted her reached port before they could obtain any information of her latest position. So they were never able to carry out their task; in fact, the warships instructed to destroy her appear to have been the only ships in the Atlantic which never caught sight of her. Then one day she quietly grounded on the coast of Panama, and within a short time her hull, fittings and wooden cargo had been looted by the Panaman Indians of the neighbour-

Even longer was the drift of the American schooner Fannie E. Wolsten, lost in 1891, which took four years to make a voyage estimated at nearly 10,000 miles. She was abandoned at the edge of the Gulf Stream, which immediately carried her along. When she became the nightmare of the Atlantic there were many sailors who raised the question as to whether the abandonment had not been premature. She was reported scores of times, and .there was a great sigh of relief when she was seen close to the edge of the Sargasso Sea, drifting steadily towards that wilderness, where she would presumably be safe for everybody.

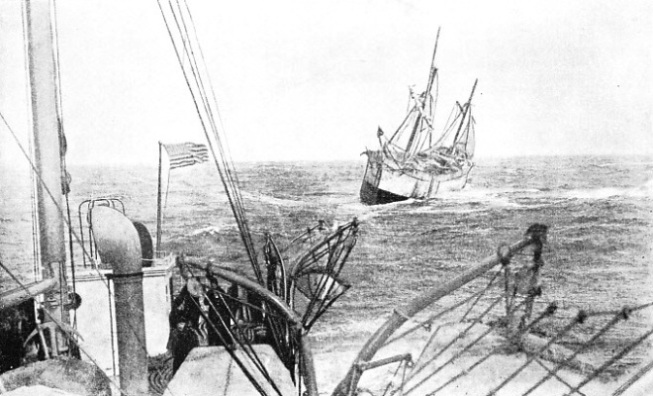

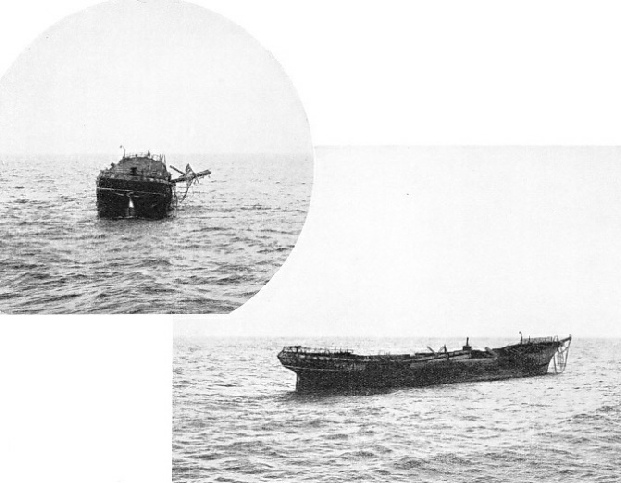

ABANDONED IN THE NORTH SEA. The sailing ship Manicia (ex-

According to the popular but erroneous belief, the Sargasso Sea, which extends across the Atlantic from the latitude of Florida, half-

For two years the Fannie E. Wolsten was forgotten, or, at least, had become nothing more than a legend, when suddenly she reappeared right in the track of coastal shipping off the New Jersey coast. All the old panic was revived, but it did not last for long; she disappeared for ever within a day’s sail of where she had been abandoned.

One more instance worth recording was that of the barque Florence E. Edgett, bound from Nova Scotia to Buenos Aires with lumber and having a crew of ten, in addition to the captain’s young wife, who proved herself a heroine. The barque was dismasted in a hurricane. Her deckload and the greater part of her bulwarks were swept away, a serious leak developed in the hull, and practically all the provisions were spoiled.

Crystal Ships

Although the accident occurred quite close to a busy trade lane, where plenty of ships were to be expected, no possible help was even sighted for twenty-

During the month in which they were on board their wrecked ship and during the further eleven days in the boat, they did not sight a single ship or vessel of any description. As soon, however, as the Florence E. Edgett had been abandoned to her own resources, she was sighted almost daily by some vessel or another and bade fair to become a terror until the currents gradually worked her into the Sargasso Sea.

Apart from the Sargasso Sea -

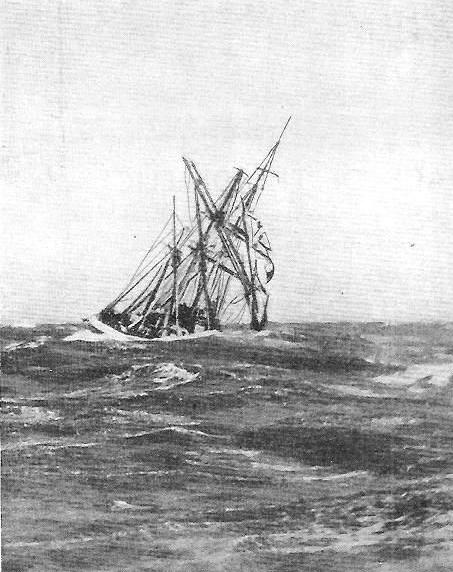

A DERELICT BARQUE, the Edward L. Maybury photographed in the North Atlantic in 1905. Many such abandoned vessels drifted for months without foundering, and it is estimated that one derelict travelled nearly 10,000 miles in four years.

The examples that have been quoted are only the most interesting or conspicuous from a long list. In the early ‘nineties the position became really alarming. In 1893 it was announced that in the preceding three years there had been no fewer than 103 casualties to British ships through striking derelicts or floating wreckage, sixteen collisions at least being definitely and unmistakably due to abandoned vessels. In the previous ten years twenty-

The year 1893 was a terribly severe winter on the Atlantic, and the following year saw a petition signed by no fewer than 830 sea captains asking that definite measures should be taken against the derelict danger, and that a proper naval search should be made of the whole Atlantic. The Admiralty and Board of Trade appointed a joint committee, but its report was not encouraging to the petitioners.

Even when the most suitable and best-

Finally orders were given that the ram was to be used as a last resource; but the USS Atalanta in 1895 and HMS Melampus in 1899 nearly destroyed themselves when ramming, and had to limp home for dockyard attention. The USS Katahdin, especially designed as a ram on lines that were decidedly unconventional, was far more useful for this purpose, but unfortunately she was so slow that by the time a report had been received and she had waddled out to the place indicated, the derelict had generally drifted another 100 miles or so.

In 1896, in consequence of the previous agitation, the Derelict Vessels (Report) Act was passed by the British Parliament, providing a fine of £5 for the failure to report a derelict at the first opportunity.

The Americans also continued to show great activity in clearing the trade lanes. In 1908 the US Coast Guard Force built one of the finest cruisers on its list, the Seneca, especially for this purpose.

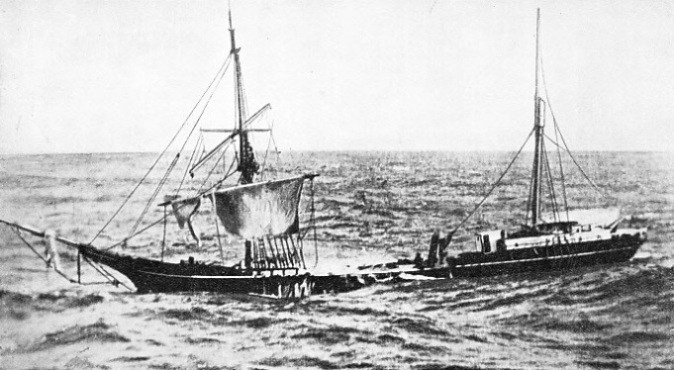

BURNT OUT. A barque, the Lysglint ex Pesca ex Blytheswood, drifting in mid-

A well-

In 1914 the Safety Convention Act was passed after the Titanic disaster. Although the Act was mostly concerned with icebergs, establishing the International Ice Patrol under the US Coast Guard, it covered derelicts as well and bound masters to report their presence by wireless if their ships were so fitted; if not, to pass the message through the first ship they encountered.

The timber trade under sail being now dead, the derelict danger has been greatly decreased if not abolished.

You can read more on “The Glory is Departed”, “The Last Days of Sail” and

“The Shipbreaking Industry” on this website.