© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Last Days of Sail

The twentieth century, with its remarkable scientific progress, its desire for speed and its overpowering economic forces, is now seeing the inevitable disappearance of the large sailing vessel.

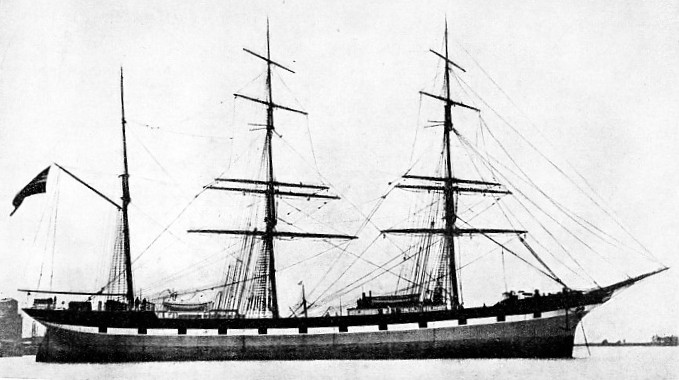

THE LAST BIG NORWEGIAN SAILING SHIP was the Pehr Ugland, a barque of 1,3’6 tons gross, built in 1891. She was 230 ft. 8 in. long, with a beam of 36 ft. 6 in. This photograph shows her at Mobile, Alabama, U.S.A., re-

ONE of the most striking, and to many people one of the saddest, features in the history of the sea since the war of 1914-

In 1914 the British Empire had 1,135 sailing vessels of more than 100 tons gross, the United States 1,386, France 523, Germany 269, Norway 516, Russia 512. Denmark 249 and Sweden 372. In addition almost every other maritime country in the world had its fair proportion.

Among the biggest sailing ship owners Bordes in France had forty-

The owners of sailing ship tonnage in the early days of the war, if they were lucky enough to be able to keep it out of the danger area, earned big freights; but the sailing ship was an easy victim for the German submarine and large numbers of them were sunk. On the other hand, many old-

So, in the tail end of the boom that immediately followed the Armistice, there was big money in sail and there was even talk of building new vessels. At that time the British flag was still worn by such well-

Sailing conditions in Sweden, Denmark and the other northern countries were similar. It was only under the Finnish flag, among the Aland Islands, that there were already signs of a complete reversal of what was happening in other countries. Captain Gustav Erikson had laid the foundation of his fleet of sailing ships which was to become the Mariehamn Grain Fleet.

Captain Erikson was born at Lemmland, a village near Mariehamn, in the Aland Islands, in 1872. He came from stock that had followed the sea for many generations. He himself started his sea career at the age of ten, and at nineteen years of age he was in command of the North Sea trader Adele. Most of his early days were spent in the North Sea timber trade, a hard life but one which produced first-

In 1913 he “swallowed the anchor” and set up as a shipowner, his first vessel being the composite barque Tjeremai, a vessel of 1,011 tons gross, built in 1883. Erikson had little money at his disposal but he possessed great ability, experience and pluck. He kept expenses down by personally buying her stores and fixing her freights, and he even cut the Tjeremai’s sails himself. His second ship came in 1914, the German iron four-

Farther south, the gigantic French fleet of sailing ships, extravagantly built and run under the forcing of the subsidy laws, was doomed by their repeal. As soon as freights began to drop the ships were laid up in their dozens, mostly in the Canal de la Martiniere, and sold off to the scrappers as opportunity offered. Captain Erikson shrewdly bought a good deal of their gear.

Two of the biggest German sailing-

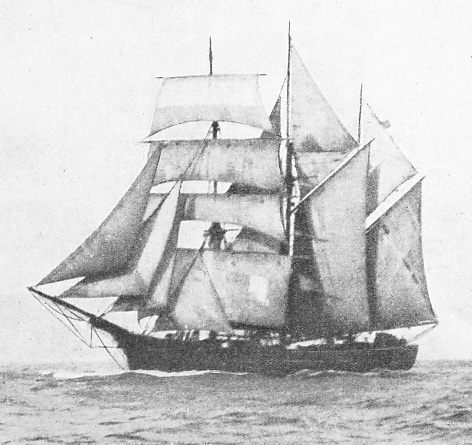

THE LAST BRITISH BARQUENTINE surviving in 1936 was the Waterwitch. Built in 1871 at Poole, Dorset, she has a gross tonnage of 207, a length of 112 feet and a beam of 25 ft. 9 in. She is used in the coasting trade, and many Trinity House pilots have qualified for their sail training in her.

When all German merchant ships of 1,600 tons gross and over, and half of those between 1,000 and 1,600 tons, had to be surrendered in reparation for the submarine campaign, the Allies were principally interested in the steamers which could carry their cargoes with the minimum of delay. It was some time before the sailing ships, fine vessels as most of them were, could be made ready to be handed over. By that time the slump had set in and few buyers could be found to run these ships.

Some of them went to the scrappers, some back to Germany, and Captain Erikson got some good bargains. When most buyers were frightened away by the thought that the Panama Canal had ruined the nitrate trade to the west coast of South America, he saw opportunities for sailing ships and he was more willing to work hard for small returns than most modern shipowners.

Sailing ships were ousted by the excessive production of steam and motor tonnage at the end of the war, much more than was needed for the ordinary volume of commerce without the post-

In the 1920 slump the dice were still further loaded against the sailing ship by changed conditions. Cargo liners, running on regular berth at a high speed, were capturing the business of the tramp, and for a long time past the tramping trade had been the only hope of sail. Consignees would no longer submit to having their goods held up for long periods at sea. They wanted to get them and turn over their money as quickly as they could.

The nitrate trade from the west coast of South America before 1914 had been the main stand-

Other difficulties were concerned with manning and gear. It is surprisingly difficult to get a good sailing ship crew together nowadays, except for training purposes. On one of the last voyages of the Garthpool, the last big square-

As the number of sailing ships has decreased, so it is no longer worth the while of ship repairers to carry a heavy stock of spars, sails and all the other gear required for repairs. Thus when one of the survivors is in difficulties the cost of repairs is prohibitive, and it is generally necessary to bring the spares and gear from long distances.

Uncovered Risks

Underwriters are nervous of writing sailing ship risks with this heavy cost of particular average. So few of them have any experience of that side of the business that they are virtually bound to lose money. Most of the surviving sailing ships, therefore, ply uninsured, or at the most insured inside limited waters when the pilot is on board. When more than a certain amount of damage is sustained aloft it means that the ship is allowed to go altogether.

The owners of sailing tonnage, who were business men, have seldom had any alternative to laying up or scrapping their ships when freights were low or when there was heavy damage to be repaired. It was the same all over the world, and all countries were affected. In some there might be particular trades which justified the expenditure of a good deal of money on repairs, in others there were owners sufficiently enthusiastic to keep their ships at sea at a heavy loss. It was a gesture for which ship lovers are grateful, but it was not business.

A great effort was made to revive sail by means of auxiliaries (see the chapter “Auxiliary Sailing Vessels”). The scheme has cropped up periodically for three-

MANY FAMOUS SAILING SHIPS still flew the British flag after the war of 1914-

In highly competitive trades the economic factor cannot be neglected, and the auxiliary is at a big disadvantage. The sailing ship’s great asset is her economy, for she gets free power from the wind; but every feature has to be as efficient as possible if she is to

compete with the steamer. Dragging the propeller through the water, even when every precaution is taken to reduce the resistance, spoils the ship’s sailing qualities.

If the auxiliary is given too much power it reduces her economy in first cost, overhead and running expenses. If she is given too little power, “just enough to kick her over a calm”, as is generally quoted, the chances are that sooner or later her people will ask too much of the engine and that it will break down, necessitating a big outlay for repairs. In any circumstances, if the motor is to be run satisfactorily, there must be an engine-

Despite these disadvantages, the circumstances were so unusual after the war that a large number of auxiliary engines were fitted into existing sailing vessels and a certain number of new auxiliaries built. Where the ship had already lived most of her life, the fitting of auxiliaries was often justified, but technically there was milch more interest in the newly-

By far the most striking were the six auxiliaries built for the Vinnen Company under the German flag. The biggest was the Magdalene Vinnen, a four-

Historic Last Voyage

The Christel Vinnen was converted into a full-

The British owners found the idea of auxiliaries unattractive for sea-

Of the famous fleet of John Stewart only the William Mitchell survived and she was a different ship from what she had been in her prime. There was no lack of apprentices, for, although sail training was no longer insisted upon by the Board of Trade, there were many youngsters who desired it. It was in finding forecastle hands and cargoes that she had the difficulty, and for some years she carried timber, wheat, guano or anything else that offered. On her last voyage she left Tocopilla, Chile, on August 30, 1927, and arrived at Ostend, Belgium, on November 25. She was then sold for breaking up and her owners were lucky to get as much as £2,100 for her. That was the last voyage ever made by a British full-

BUILT in 1880, the Fanny Crossfield is one of the last British sailing coastal craft. A wooden three-

The Garthpool, a steel four-

All this time Gustav Erikson’s fleet was steadily growing. He was a thoroughly practical sailor with a good eye for a ship and a careful business man who could weigh up the chances of any vessel that took his fancy. He had also strength of will to check his natural enthusiasm for the tall ships that he loved so well. One by one, generally at a small price, he collected just the ships that he wanted and some famous names appeared in his fleet. It is typical of the man that when a ship which had borne a name with great credit had been renamed by subsequent owners she was always given back her original name at the first chance.

The sailing ships Lawhill, Herzogin Cecilie, Olivebank, Killoran and many other well-

It is difficult to imagine any other man producing such remarkable results as Captain Erikson has done since 1918, but it has only been by unremitting hard work and constant personal attention to the tiniest detail. So few opportunities of sail training now exist that he has no difficulty in finding his crews of youngsters who are keen on taking their chance, and fine crews they are. The cost of insurance is prohibitive, and he has had to decide to take his chance of loss. Occasionally one of his big ships may come to grief, and the only thing to do is to write her off, and, if possible, salve her gear and adapt it for the other ships of the fleet.

All the time he and the other surviving sailing ship owners have to tackle the difficulty of finding business. The South Australian grain trade is the mainstay of the big sailing ship to-

In 1921 there were thirty-

Even Erikson cannot be seeing much profit after his expenses are paid. The outward ballast passage has to be paid for, and it is generally reckoned unofficially that it costs a pound a ton without any allowance for depreciation.

Out and Home in Ballast

The rates in this business vary considerably; sometimes they are over thirty shillings, but more often between that figure and a pound. Sometimes they are less, and in 1930 the Penang, rather than accept thirteen shillings a ton, the best that was offered, came home in ballast as she had gone out, her year’s work being purely for the benefit of the hands that she was training. How long this business will last in the present trend of trade cannot be foretold, but nobody is ever likely to build another big sailing ship. The last days of sail, therefore, appear to be numbered by the lives of the present fleet.

The quebracho or logwood business was another trade which employed a number of sailing ships for many years, dating back to the middle of the sixteenth century at least. In 1918 Dufour Brothers, of Genoa, began to run a fine sailing ship fleet, one of the last left under the Italian flag, on this trade. After they had given up, the three Danish barques Germaine, Claudia and Suzanne, remaining under the Danish flag according to the will of their owner, carried large quantities of logwood to France. Until she was broken up in 1935 the Italian barque Letizia, their last sea-

The Baltic timber trade formerly employed a large number of square-

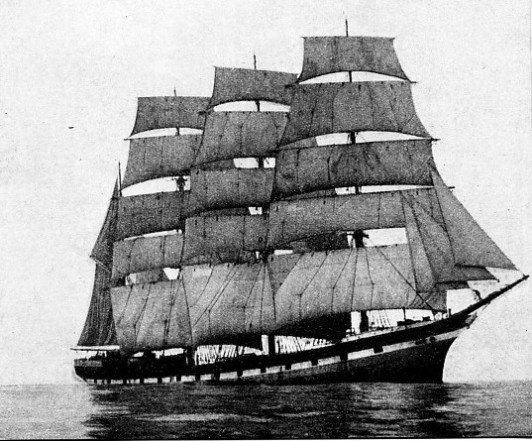

UNDER FULL SAIL. The steel four-

The majority run to the River Thames, where they are always known as the “onkers”. This name has puzzled students for many years, although it was apparently founded on nothing more than the windmill pumps that these ships used to carry. Their monotonous sound, “onk-

The various trades that formerly existed for the American sailing ships — up and down the coast, from the eastern seaboard to the Atlantic Islands and from the western seaboard to Hawaii — have also disappeared rapidly, although they employed a large number of vessels, mostly the multi-

These ships included some well-

The New England States still contribute a number of schooners, nowadays mostly with auxiliary engines, to the Grand Banks fisheries and those nearer inshore. These schooners for some years past have been built on yacht lines and are engaged on the fisheries only. On the other side of the border similar vessels not only fish but many of them also carry their catch of cod, salted down, to the Catholic countries of Southern Europe. They return with cargoes of salt for the next year’s catch.

Grand Banks Fishery

Such cargoes are hard on tiny vessels — many of them under 100 tons — battling their way against the “Brave West Winds”. Every year, unfortunately, sees the number of this gallant fleet reduced by foundering.

The Grand Banks fishery is of great antiquity, dating back to the early sixteenth century. It attracts sailing vessels not only from the United States and British North America, but also from France and Portugal. In 1914 there were no fewer than 317 sailing vessels in the French Grand Banks and Newfoundland fleet. In 1930 the number was sixty-

The fleet still leaves the Breton ports every spring with its old-

There is considerable international competition in the Grand Banks fleets and, at intervals since 1922, the International Schooner Race between American and British North American schooners has attracted great attention. One of the champion schooners in this race, the Nova Scotian Bluenose, crossed the Atlantic for King George’s Silver Jubilee Review in 1935 and was greatly admired.

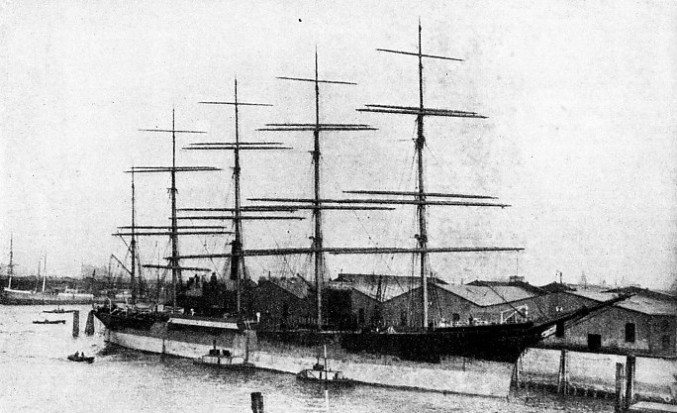

FATED TO BECOME A TOTAL LOSS, the Potosi was a five-

Allied to the Grand Bankers, the sailing vessels of the Greenland fishery are also rapidly disappearing. Before 1914 there were numbers of them, mostly ketches and schooners of modest tonnage, going out to the fishing grounds every year. The modern trawler, with her economical engines and big radius of action, has ruined their business and only a few of them remain. Those that do, however, are fine little vessels with a particularly high standard of seamanship.

The local trades in various parts of the Indian Ocean still support a number of sailing vessels. Some of these are of local type, but one or two barques have survived until recently. The last under the British flag was the iron barque Diego, a 400-

Until the war of 1914-

Among those still to be seen are the Brooklands, of 1859; the Emily Warbrick, of 1872; the Jane Banks, of 1878, the Irish Minstrel, of 1879; the Fanny Crossfield, and others. Perhaps the best known of all is the Waterwitch, the last surviving British barquentine. She satisfies the requirements of Trinity House for square-

Revival of Sail Training

All these surviving sailing vessels, large and small, are carefully studied by a considerable band of enthusiasts and a number of people desire to travel in them as passengers. In Erikson’s fleet there are several ships with excellent passenger accommodation, especially those which were originally built as training ships rather than for trading. They generally have a few passengers at a daily rate, as it is regarded as impossible to quote a fare for the voyage because of the uncertainty of its duration.

Since the British ocean-

Apart from purely naval sail training ships, the Abraham Rydberg and C. B. Pedersen train future Swedish officers. The Sorlandet, a full-

The Danes have the magnificent auxiliary Danmark built in 1932 for the Government after the Kobenhavn, which was run by private enterprise, had disappeared at sea with all hands. They also have the Georg Stage, another auxiliary. Poland has the Dar Pomorza, and Finland the Suomen Joumen, which offer training for the Navy as well as for the Merchant Service. Russia still owns the steel four-

Of the German sail-

There are still a few old sailing vessels laid up in various odd corners of the world, but most of them have been idle for a long time with their gear rapidly deteriorating. It is not likely that they will ever be recommissioned to stave off the inevitable day when the beautiful sailing ship, for trading purposes, is a thing of the past and only a memory to those who suffered many hardships and discomforts but loved her just the same.

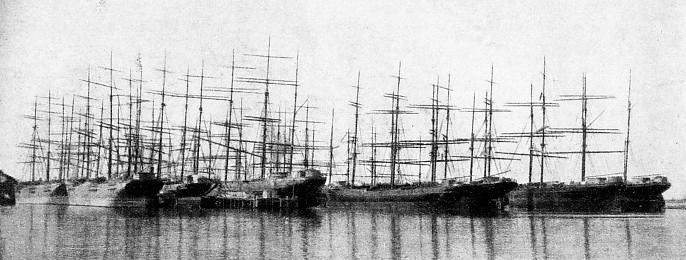

THE ALASKAN PACKERS FLEET in 1922 consisted of twenty-

Click here to see the photogravure supplement to this article.

You can read more on “Auxiliary Sailing Vessels”, “Romantic Sailing Coasters” and

“Training in Sail To-