© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Mariehamn’s Grain Fleet

On the counters of most of the large sailing ships of the world appears the name of Mariehamn, a tiny port set in the Aland Islands of the Baltic Sea. Every year its famous vessels bring cargoes of wheat from Australia to England

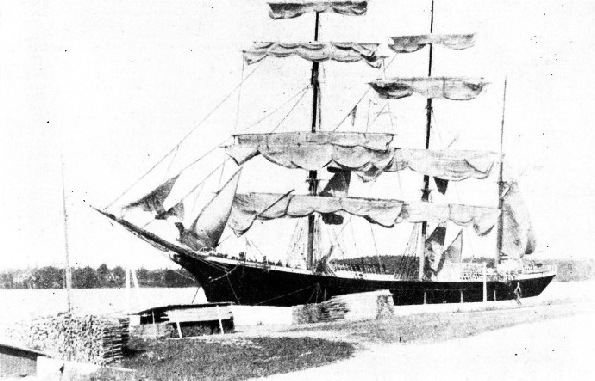

WALLAROO PIER in Spencer Gulf, South Australia, where Mariehamn grain ships take their golden cargo of grain aboard. In the centre of this photograph are the Invercauld and the Mashona. These ships were built in 1891. The Mashona, a four-

EVERY year, in early summer, the end of the so-

A real spirit of rivalry does exist between ship and ship, and individual performances are the subject of keen discussion among the sailing fraternity, but to regard this annual sailing from Australia as a speed contest is incorrect. The participants are unequally matched in tonnage and in rig, and there is no common starting point or time. No two vessels contend with precisely similar conditions of weather, nor do they always maintain identical courses.

The majority come home by Cape Horn, the old “Sailor’s Way” of the racing wool clippers, but every captain is at liberty to choose the longer and quieter alternative of a passage round the Cape of Good Hope. The choice is often decided by the prevailing conditions in the Australian Bight, and a prudent ship-

Neither the Panama Canal nor the Suez Canal is of much help to the sailing ship from Australia. The canal dues are high, and the adjacent climatic areas are unsuited to the heavy-

MOORED TO THE PINES and to ring-

Sixteen thousand miles of lonely sea lie between South Australia and England, for the sailing vessel does not use the same direct routes as the steamer, to which, by comparison, wind and weather are of little account. The wind-

Grain is an almost imperishable cargo. It carries well and is little affected by the hundred days’ passage of the average sailing ship from Australia to Great Britain. No seasonable markets are lost by the extra weeks of transit. The free warehousing afforded by the vessel may operate in her favour. It generally happens that her cargo is sold and resold several times while she is at sea, and the margins of a rising grain market may make even the slowest sailing-

This carriage of grain from Australia to Europe offers regular employment to the big sailing ship. Sail chartering is entirely in the hands of one London firm, and the cargoes go to British buyers and the ships to British ports. An occasional cargo may be sold to Continental buyers, depending on the state of their markets.

The square-

Captain Gustaf Erikson of Finland is largely responsible for the continued existence of the famous grain fleet of sailing ships, except for the Parma and the two Swedish vessels Abraham Rydberg and C. B. Pedersen. The two German ships Padua and Priwall, for a time in the Australian grain fleet, have now reverted to the Chilean nitrate trade.

Erikson went to sea as a cabin boy at the age of ten, was successively cook, bo’sun and mate, and, when nineteen, the skipper of a little wooden Baltic sailing vessel. From 1902 to 1913 he was a master-

The shipping slump after the war of 1914-

Underwriters have paid no loss on any cargo in an Erikson ship between 1918 and 1936. Of his two total losses in that period, one ship, the Hougomont, was in ballast; in the other instance, that of the Melbourne, the monetary loss was reimbursed by the colliding steamer, as the steamer had been at fault.

Year by year this epic fight to keep sail upon the seas becomes more bitter. It has been estimated that in wages, food, charges and general upkeep, it costs to-

With grain freights at, say, twenty-

For many years coal, nitrate, timber, guano and such cargoes have become the perquisite of the steamer, yet sail can still obtain a grain charter.

For many years coal, nitrate, timber, guano and such cargoes have become the perquisite of the steamer, yet sail can still obtain a grain charter.

A long, shallow arm of the South Pacific Ocean penetrates 200 miles into the interior of South Australia. Spencer Gulf, as this arm is called, provides a direct outlet for the great South Australian wheat belt in conditions that are as favourable to the sailing vessel as to the steamship.

FROM THE LONDON RIVER the Loch Linnhe sailed on her last voyage in 1933. She was considered too small (1,346 tons gross) for the Australian grain trade and was returning to Mariehamn in ballast. As she approached her home port on November 5, she went out of her course and was driven ashore. No lives were lost, but she broke up beyond hope of salvage. The Loch Linnhe was an iron vessel built at Glasgow in 1876.

Scattered along the shores of Spencer Gulf are many small outports, consisting perhaps of a general-

At most of these little ports the vessels load at the quayside, but at Port Victoria and at Port Broughton the cargo is loaded from lighters into the sailing ships. They lie at anchor out in the quiet roadstead a mile or two off shore, swinging at their cables in the blazing midsummer sunshine of an Australian Christmastide, the height of the golden harvest of the South.

By rail, lorry or wagon team, the grain comes to the jetties from the great country farms. It is transported by local ketches and schooners to the waiting ship where the stevedores, using the ship’s own tackle, stow it, bag by bag, into the capacious holds.

Before an inshore berth can be reached, the big sailer must be lightened of the ballast that she has carried all the way from Finland. Lucky are the crews of the few ships that are wholly or in part ballasted by water, for the discharge overside of 1,500 tons of stone, gravel or rubble is a long and back breaking task. The gravel has to be loaded into baskets in the stifling heat of the lower holds, and then hoisted up and swung outboard by block and tackle to be discharged.

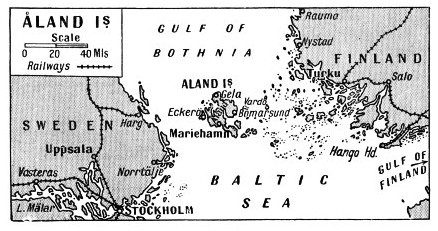

The Aland islands are situated in the Baltic Sea between Finland and Sweden. There are more than 6,009 islands in the group. Mariehamn, the home port of Erikson’s grain fleet, is the capital of the islands which form part of Finland.

The high overheads, wage bills, port charges and demurrage of the steamship make rapid loading an economic essential. She must berth alongside the giant elevator or the travelling cranes of a modern port. Her golden cargo must pour in through several hatches simultaneously. The one month or occasionally more spent in the primitive loading of the sailing ship in the Spencer Gulf would spell ruin to the steamer.

Many years ago the barren coast of South Australia which borders the Great Bight received from the seamen-

One day, in May 1932, a 3,000-

Seventeen days earlier, when nearly at the end of her long outward ballast voyage from Europe, she had been caught in one of the fierce and sudden gales that have earned for the Australian Bight its unenviable reputation among seamen.

When the gale had abated and the dangerous confusion of fallen spars and gear had been cut away, the Hougomont looked a sorry derelict For more than 500 miles she crawled under jury rig, a pitiful travesty of her former beauty, until she made what was to be her last landfall. She fell in with a solitary steamer during the passage and received an immediate offer of towage. This was refused by the signal: “All well, no assistance required”.

A FOUR-

It was a remarkable piece of seamanship, rarely matched in these days of steam and wireless. A dismasted, uninsured sailing ship to-

Even towards the close of the nineteenth century the great seaports of the world always presented the lovely pageant of a great company of tall ships berthed together. Circular Quay at Sydney, the San Francisco waterside, the docks of Liverpool, the roadsteads of Chile, London River -

The fortunes of modern deep-

Aland is a sea-

When, in 1917, after the Russian Revolution, Finland became an independent republic, both she and Sweden laid claim to Aland. A referendum proved favourable to a Swedish union, for in language, manners and customs the islanders were far more Swedish than Finnish. Sweden, however, relinquished her claim, and by its first settlement of a major territorial dispute, the League of Nations in 1921 gave Aland to Finland.

There are Viking graves at Godby in Aland, and the Viking blood would still seem to flow in Aland veins. The situation of the islands attracts men to the service of the sea. Few communities to-

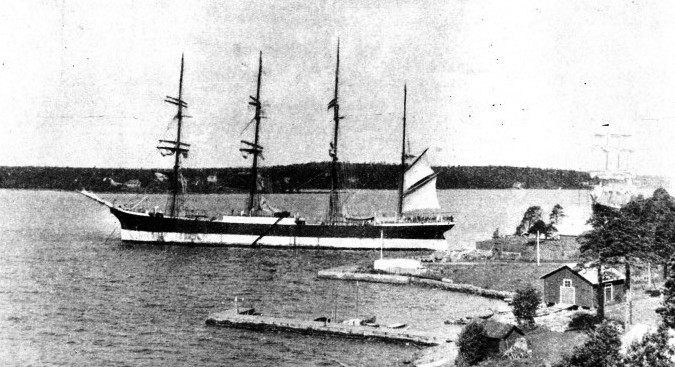

THE ALAND ISLANDS of the Baltic Sea afford shelter for ships of the Mariehamn grain fleet, which may often be seen at anchor or moored there. This photograph, taken in 1934, shows the steel four-

To-

Mariehamn Harbour is most spacious, and resembles the shape of an hour-

Little Use for Tugs

It happens but rarely that the whole of Erikson’s fleet reaches Mariehamn in any one autumn. One or two vessels may have been fortunate enough to sail again at once for South Africa or Australia with one of the few cargoes of timber now on offer from Sweden or Finland. An occasional vessel still gets a cargo of guano from one of the Seychelles Islands to New Zealand. Others too tardy in their arrival in England may sail straight out to Australia again after they have discharged their grain, and for two years not see home. In early September the rest will leave the Baltic outward bound.

There are few roads, and fewer motorcars in this northern archipelago. Here are farms in which every field is a separate islet. There are a school for sea-

The few pilots of Mariehamn, all themselves ex-

AFTER THE VOYAGE FROM AUSTRALIA the Penang dries her sails at Mariehamn. The photograph above shows the Penang from a more distant position. She is a steel barque of 2,019 tons gross. Built at Bremerhaven in 1905, she is 265 ft. 8 in. long, with a beam of 40 ft. 3 in. and a depth of 24 ft. 4 in.

About half-

Suddenly, with all the fickleness of a doldrums squall, the wind veered round to the north of east and, strengthened to half a gale, accompanied by such blinding rain that all trace of land was blotted out. The pilot roared out the order to put the ship about, the mate’s whistle shrilled out its triple call for “All hands on deck”, an extra man was sent to the lee wheel, and within a few minutes the Penang was sweeping round in a wide arc. In due course she stood out again to the safety of the open sea.

The next few dismal hours were spent tacking backward and forward away to the south of Mariehamn. There was a heavy, lowering night sky, with driving rain and a strong north-

So close in did she sail that night that next morning she was warped to the quay by hawsers at bow and stem, led to her own capstans.

Erikson’s Grain Fleet

Registered at the little port of Mariehamn and owned by Captain Erikson are some of the biggest sailing ships in the world. The Penang, 2,019 tons gross, was built at Bremerhaven in 1905. Her length is 265 ft. 8 in., her beam 40 ft. 3 in. and her depth 24 ft. 4 in. The steel four-

Slightly larger than the Pamir is the Lawhill, 2,816 tons gross. She was built at Dundee, Scotland, in 1892. Her length is 317 ft. 5 in., her beam 45 feet and her depth 25 feet. The Grace Harwar was also built in Scotland, but three years earlier and at Port Glasgow. She had a gross tonnage of 1,816, a length of 266 ft. 8 in. and a beam of 39 feet. She was broken up at Charlestown, Fifeshire, in the summer of 1935.

One of the later additions to Erikson’s fleet is the L’Avenir, 2,776 tons gross. She was built in 1908 at Bremerhaven. She has a length of 278 ft. 3 in. The gross tonnage of the Viking, another of Erikson’s fleet, is 2,670, but her length is 293 ft. 10 in. She has a beam of 45 ft. 11 in. and a depth of 23 ft. 10 in.

In 1935, the steel four-

The pride of Erikson’s grain fleet was the famous Herzogin Cecilie. Her history is told in the chapter beginning on page 127. She was one of the largest sailing ships afloat, with a gross tonnage of 3,111. Her mainmast was nearly 200 feet high and she set 46,000 square feet of sail area. Built at Bremerhaven in 1902, she had an overall length of 335 feet and a beam of 46 feet. In April 1936 this great ship went ashore in a dense fog between Salcombe and Hope Cove, in Devonshire.

SUMMER IN MARIEHAMN HARBOUR sees many of Erikson’s grain fleet at home between their annual voyages to Australia for wheat. This photograph, taken in August 1935, shows in the foreground the steel four-

Click here to view the photogravure supplement to this article.

You can read more on “The Herzogin Cecilie”, “In the Sailing Ship’s Forecastle” and

“Speed Under Sail” on this website.