© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

In the Sailing Ship’s Forecastle

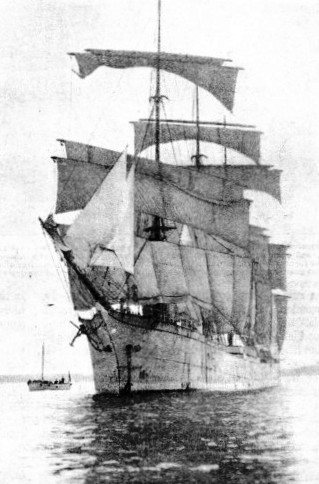

The “shell-

GOING ALOFT. However uncomfortable the forecastle may appear to the landsman, it is a welcome refuge to the forecastle-

MANY landsmen have wondered -

When a man is living in one place for months, or perhaps for years, his environment has a large influence both on his health and on his mentality, and the old “shell-

The question of health was generally neglected, although it was obvious that the healthy seaman could work better than the one who was ailing. Eating in the most uncomfortable conditions meant hurried food, and that had its effect on even such a hardy individual as the sailor. In British ships few of the forecastles had tables. There were some exceptions where proper mess-

The man who was shanghaied (drugged and shipped) into the forecastle of a sailing ship, as so many were, had little chance of obtaining even these amenities from the crimp who had sent him to sea. His discomfort was increased accordingly, except for the charity of his mess-

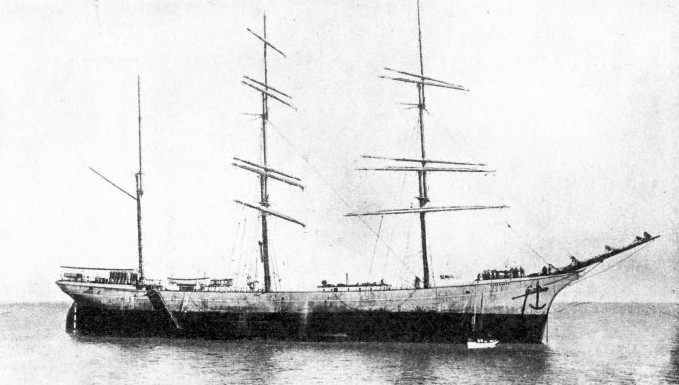

THE LAWHILL, a modern sailing ship, in which the forecastle-

The sea chest of the old sailor was such a feature in most forecastles, British as well as foreign, that it is worth describing. Sometimes it was quite elaborate, made of cedar wood and bound in brass. It was generally possible to get a really good sea chest for twenty shillings. Often the ship’s carpenter invested in a supply of wood when the ship was at one of the timber ports; he made the wood into chests on the way home. These he sold at a good price to his messmates or seamen ashore. Both men and boys took great pride in their chests, and spent much time in decorating them.

The inside of the lid carried pictures of ships and geometrical designs, not, perhaps, of artistic merit, but neatly done and entailing considerable work; the handles were decorated with really beautiful rope work and the shackles with fancy knots. They provided excellent practice for the first voyager in one of the primary jobs of sailorizing. In French ships there was generally a lace-

Sleeping Accommodation

In later days the kit bag came into favour. For a long time the mates maintained that the old “reliables” had sea chests, while the youngsters and scallywags had bags, as they were much handier for deserting. Their increased convenience and better stowage, however, brought them into general use, and the sailorizing instinct of the men found an outlet in fancy rope designs worked into the bases.

The men worked so hard that sleep generally came by sheer exhaustion, and the sleeping accommodation received but little attention. In the old days the men were accommodated in hammocks, Navy fashion. In some of the old North Atlantic timber droghers (timber carriers) the after bulkhead of the forecastle was unshipped to make room for the ends of the logs in the deck cargo. In these vessels the hammocks, one for every two men, were generally spread on the ends of the logs.

American ships introduced bunks -

Sometimes the two watches, port and starboard, chose their bunks on the same system, to save disturbing a sleeping messmate when a man from the watch on deck went down into the forecastle to get anything. All prearrangement, however, went by the board when leaky decks made the upper bunks untenable, and each seaman had to “double-

The sailor’s usual mattress was the traditional “donkey’s breakfast” stuffed with straw: such a mattress could be bought for a shilling or eighteenpence in any of the seaport towns, and it was nearly always too narrow for a bunk of standard width. Because it was difficult to remain on when the ship was rolling it was often called a “razor strop”. British seamen generally provided themselves with two dark-

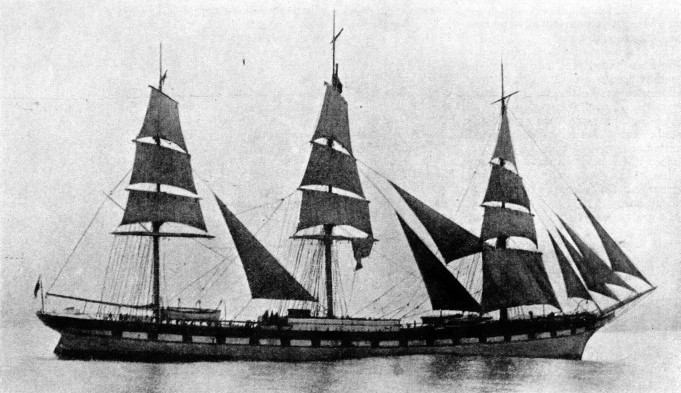

THE INVERNESS, a modern three-

With such gear it was generally necessary for the men to sleep in all, or in most, of their clothes. Under the Laws of Oleron, framed about 1190, it was a serious offence to undress during a voyage. Many Continental seamen, however, preferred to undress for sleep, and the French favoured a flannel night shirt of astonishing thickness, and nine times out of ten of a vivid red colour. The modern sailing-

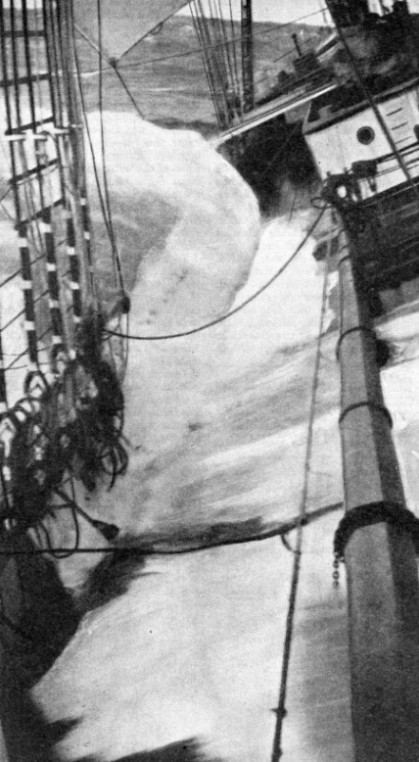

This allowed much water to come straight through into the forecastle, only a small portion being diverted by the breakwater built across the deck. When the ships were out of soundings the anchors were unshackled and made fast on the forecastle head, the cables were drawn inboard and the hawse-

In some ships -

To live in any top-

Generally the deckhouse forecastle was far more comfortable and far more popular with the men, although for many years it was comparatively rare in British ships. Numerous foreign ships had it as a matter of course and in addition provided separate forecastles for each watch, with a comfortable mess-

SHIPPING A HEAVY SEA. One of the principal disadvantages of the deckhouse forecastle -

A development of the deckhouse forecastle was the “Liverpool House” or “midship house”, stretching across the full width of the ship. It gave better accommodation, and was only occasionally flooded, but it had disadvantages. It was much in the way when the ship was being worked, for there was no direct path through it. The crew had to climb up and down ladders when going fore and aft. As a rule entrance was from the upper deck only, with small ports at the sides, making it difficult to ventilate in the tropics. All deckhouse forecastles except the Liverpool house were exposed to the risk of having the sides stove in by heavy seas; in unusually bad weather some of them were swept overboard bodily with the seamen inside.

One of the greatest -

D espite such conditions, a seaman who said he was ill was regarded with even more suspicion by his mates in the forecastle than he was by the afterguard, who were brought up in the belief that no seaman was ever sick, only lazy. Castor oil was considered the remedy for all ills. Strangely enough the hands nearly always developed coughs and colds as soon as the ship was in port when the hard conditions had somewhat relaxed. Numbers of the men died of pneumonia, and in their old age the great majority suffered agonies from rheumatism. It is surprising more did not die on board, for in most ships men were told, “If you are sick, ten minutes is enough for you to die; if you are still alive by that time, turn to and work.”

espite such conditions, a seaman who said he was ill was regarded with even more suspicion by his mates in the forecastle than he was by the afterguard, who were brought up in the belief that no seaman was ever sick, only lazy. Castor oil was considered the remedy for all ills. Strangely enough the hands nearly always developed coughs and colds as soon as the ship was in port when the hard conditions had somewhat relaxed. Numbers of the men died of pneumonia, and in their old age the great majority suffered agonies from rheumatism. It is surprising more did not die on board, for in most ships men were told, “If you are sick, ten minutes is enough for you to die; if you are still alive by that time, turn to and work.”

SAFETY PRECAUTIONS. Dry clothing is a luxury denied the forecastle-

The possibility of sailors catching a chill when they went on watch was generally used as an excuse for not providing adequate heating facilities in the forecastle. A small bogey stove was all the heating apparatus that was generally found; but sometimes even this was omitted. Improvised bogeys were easily made with a paint drum and a little piping, but they were apt to be extravagant in fuel, and fuel was difficult to get. Even their small heat was a great comfort off the Horn; but, while such a stove dried the place to a certain extent, it put the forecastle in a state of continuous fog. It woke up the bugs, normally inconspicuous in those waters, and the back wind from the sails always prevented it from drawing properly. The argument as to whose job it was to clear the ashes, if there happened to be no boy, to whom the work went automatically, often led to so much bad feeling that the stove was thrown overboard to restore harmony.

The men’s quarters were lighted as badly as they were heated. For natural light there was the scuttle, closed in bad weather to prevent heavy water from coming down; there were sidelights frequently, but occasionally only bullseyes in the deck. Artificial lighting in many forecastles was provided by a “slush lamp”, generally a preserved meat tin filled with fat from the galley, begged or stolen from the cook. The wick was made from the shredded canvas of discarded sails. The name “slush lamp” persisted after colza oil had been substituted for the galley fat, and paraffin for colza.

“Milking” Oil

When there was a proper lamp some captains objected to it on the score that it endangered-

Getting extra supplies of oil and replacing broken glasses were among the constant problems of the forecastle. It was usually necessary to call in the assistance of one of the apprentices whose job it was to rouse the officer of the watch. He generally slept soundly. Before he was properly awake there was the opportunity of “milking” his lamp of the greater part of its oil, while the pieces of broken lamp glass were always carefully preserved to be scattered on the deck of the officer’s cabin, his own unbroken glass being extracted and taken away forward. Foreign ships were better supplied with illuminants than British.

In some trades, notably the China trade, ordinary lamp oil was often difficult to get, and coco-

The ventilation of the crew’s quarters did not present so many problems to the owner, for the sailing ship man hated fresh air in any circumstances -

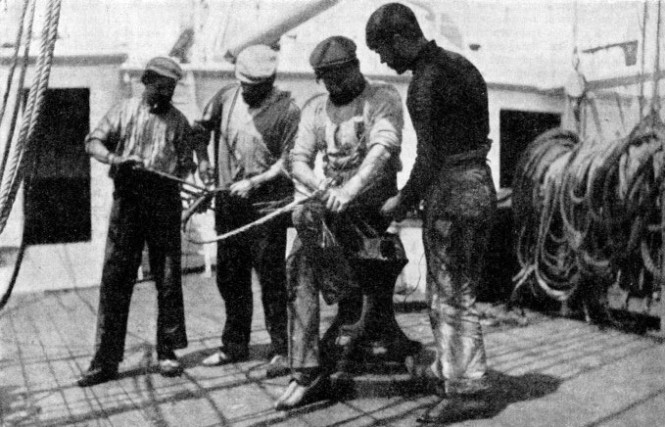

WEAR AND TEAR ON THE RIGGING AND SAILS necessitate continuous overhaul and repair. This is one of the pleasanter tasks of the,crew but it calls for all the seaman’s manual dexterity. In all weathers there is a continuous strain on the rigging, and the many-

Another cause of infinite discomfort in the forecastles of the old sailing ship was vermin. Some cargoes and some trades were worse than others. Coal cargoes, which occupied so many sailing ships, brought thousands of fleas on board, for no apparent reason, as did also the wool cargoes from Australia. In hot weather the fleas came up the ventilators in hundreds and when the hatches were taken oil all hands were scratching. The bone trade from the River Plate to the Mediterranean was a particularly unpleasant one; fragments of meat were generally adhering to the bones when they were shipped and bred maggots that penetrated everywhere, not only into the living quarters but even into the harness cask and bread barge.

Weevils were expected in the hard biscuits, “Liverpool pantiles”, and the like, which were dignified with the name of bread; they were easily knocked out by rapping the edge of the biscuit sharply on the table. Compared with bugs, the cockroaches that infested nearly all sailing ships were regarded almost as domestic pets by the men; they were comparatively harmless and were generally called “domestic animals”, or “fresh meat” if they found their way into the food. They even appeared on board a brand new steel ship, although it was a puzzle how they got there.

There is an old fable that cockroaches and bugs will not live together, but any old “shell-

Dangerous Cleanliness

Some careful captains had the forecastle completely turned out every Saturday morning and painted with creosote, but as a rule that was only a partial cure. The old sailor maintained that the only thing to kill bugs was paraffin. A common device was to allow the paraffin to run down the seams of the woodwork. It was then set alight. One or two hands stood by ready to beat out the flames if the safety of the ship was threatened. As every shipmaster was by hard experience nervous of fire, this method of exterminating “livestock” was disliked officially,but it was generally employed. The usual official method of fumigation was to bring a chain up to red heat and dip it into a bucket of tar in the forecastle, making the quarters chronically uncomfortable, for men as well as for vermin. This practice was the cause of many disastrous fires, for a bucket is easily capsized in a violently pitching ship.

Although cockroaches, bugs and the like were regarded with complacency in practically every forecastle, the seaman who was personally verminous committed an unforgivable crime, and his messmates undertook to cure him.

Rats were so prevalent in the old sailing ships that the proverb about rats leaving a sinking ship became worldwide. Probably the reason was that the unseaworthy ship gave plenty of notice of the approaching disaster. In moderation these vermin provided diversion, since rat hunts made a break in the monotony of the voyage.

The forecastles themselves were generally kept clean by the men’s own desire; if the afterguard did not give the men the opportunity as a job of ship’s work, the forecastles would be scrubbed out during the Saturday morning watch below.

Nowadays, of course, the numerous inspectors of the various Port Sanitary Authorities take the greatest pains to ensure that the seamen’s accommodation shall be kept clean.

FORECASTLE ACCOMMODATION was provided amidships in the Speke. Built at Milford Haven in 1891, she was one of the largest British three-

You can read more on “The Last of the Giants”, “Romance of the Racing Clippers” and

“Speed Under Sail” on this website.