© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Sailing Round the Horn

A vivid first-

CAPE HORN, where the Atlantic and Pacific meet, has always been a terror to seamen sailing round it. It is situated at the southern extremity of South America, on a Chilean island in the Tierra del Fuego Archipelago. The Dutch navigator Schouten discovered the cape in 1616 and named it after his birthplace Hoorn, in Holland. Cape Horn consists of steep black rocks rising to a height of 1,390 feet.

THERE are still a number of men left who, in the first few years of the present century, made the passage in sail round the Horn — the last of a generation to do so. I do not count the few sailing ships built after the war of 1914-

The barque in which I served my time was of a well-

Our Old Man was a weather-

Never have I seen so much remorse and bitterness in a man. Life was simply not worth living for him, and as we neared the Horn, and the cold began to bite into even us youngsters, I used to watch old Cassey in his thin, worn oilskins, borrowed from somebody, as he crept round the decks, a pitiable picture.

Then there was Brown, a magnificent young seaman, the leader of the starboard watch, and Ohlsen, a Swede, who led the port watch. There were six of us apprentices in the half deck, and long before we had sighted the Falklands in a flurry of snow, we were alarmed by the yarns that the old sailors used to pitch us about the terrors and rigours of the Horn.

It was, certainly cold. We had bent on a new suit of Number One canvas and had taken the precaution of overhauling all the running gear.

We soon ran into bad weather but, instead of letting the watch on deck huddle under the fo’c’sle head, or under the break of the poop, the Old Man made us clean brightwork on the poop with sand and water. It was the coldest job I have ever had to do.

What made us feel the cold so much was the lack of sufficient hot food. As the days grew shorter and the temperature lower, the bad weather increased, and soon we were shipping it green over the weather bulwarks. Unfortunately, the after part of the iron deck-

Nothing can exceed the squalid misery of those days. Our half-

These six bunks were our cells in which we lay when off watch, shivering with wet and cold while the water slopped and gurgled beneath us. Unfortunately, my bunk was six inches too short and I could never straighten my knees.

To be frozen is sheer misery; to be sleepy and yet be unable to sleep because one is on watch is sheer misery too. But to be both frozen and sleepy is indescribable. I do not think any one can realize what a miserable time it was, and the only comparison I can think of is the winter in the trenches on the Western front during the war of 1914-

The Worst Cry of All

There a man had a good chance of being killed, while we ran the risk of being drowned or swept overboard; but anybody who has spent a winter in the trenches in France will have a good idea of a long passage round the Horn in winter time in a square-

We six apprentices were all growing lads, and the one thing needful was food. But she was a Scots “barkey” and there was never enough for our ravenous appetites, sharpened by wind and wet. When, in addition, it became impossible to get any hot food or drink owing to the galley being out of action, even some of the tough nuts in the fo’c’sle began to lose the smile off their faces.

The struggle with Cape Stiff — as the Cape is known to the old sailingship man — found us ill-

always seemed to come at midnight: “All hands reef the foresail”. Then the watch on deck, already stiff and frozen, would wait its chance until the watch below, also waiting its chance, jumped out of the fo’c’sle door and made for the fore rigging. Up we would go, wearily climbing aloft, to spread ourselves out along the yard, our feet on the foot-

This Number One canvas was wet through, icy and as hard as iron. Our frozen fingers could never get hold of it. The wind blew our oilskin coats over heads; the lee yard arm surged swayed close down to the foaming below which seemed to be leaping up at us. Occasionally an extra gust would belly out the canvas, tearing it from our feeble grasp so that we had to begin all over again.

Our able seamen — and superb tradesmen they were — received three pounds a month or fifteen shillings a week for this super-

Sometimes, after two hours or so on the yard, the Old Man, gloomily watching our efforts from the poop, would bellow through his megaphone to the second mate to leave it and bring the men down. Sometimes, if he thought he would lose a sail unless we got it safe under the gaskets, he would just leave us there, hour after hour, until we had no more fight left in us. Even if we did manage to save his-

That is where the meanest tramp had the advantage over us. In a tramp steamer there was always a fire somewhere, even if you had to go to the furnaces for it, but in that old iron tub. a mere floating warehouse, there was no heat at all except in the cabin, and no apprentice or A.B. dare show his nose in there.

The effect of this exposure and lack of hot food began to show itself. One of the men went sick with salt-

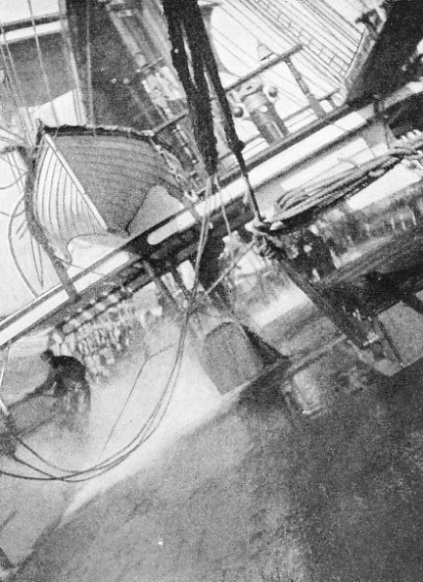

A HEAVY ROLL during a squall when rounding Cape Horn. This photograph, taken in the Garthsnaid, one of the last of the famous British sailing ships, shows in a remarkable way the angle to which a vessel may roll in a heavy sea.

The rest of us must have looked miserable creatures that night. We had been nearly three weeks in this condition, beating against a southwesterly gale that seemed to have no end. Sea after sea would come roaring up, rearing its ugly head as it swept down on us. It was not safe to be on the main deck, so that the watch on deck spent its time on the poop, where we lashed ourselves to the lee rail with the braces.

Against the sky our goose-

Daylight came about nine, and occasionally we could catch a glimpse of a pale watery sun which rose above the horizon after ten o’clock and set before three.

Then, suddenly, one morning the whisper ran round the ship: Cassey was dead. The Rajah, as they called him, had put up a good fight, hut cold and exposure working on his enfeebled frame had laid him low. The sail-

The mate had called out to me to hoist the ensign on the gaff halyards at half mast, but the skipper stopped him, He didn’t want his flag blown to ribbons in that gale, he said.

Then, as we stood there, keeping our feet with difficulty, I suddenly caught sight of a big steamer about a mile away. She was coming down before the wind at a great pace, lifting and plunging into the following sea, the wind blowing her smoke far ahead of her.

“A Pleasant Voyage!”

Suddenly a string of bunting was run up on her foremast and the Old Man called to me to run into the cabin and get the signal book. He shouted down to me through the companionway: “It’s T C Z.” He had been looking through his telescope.

I hastily ran my finger down the three-

“It means a pleasant voyage, sir!”

The irony of the signal was lost on me, but as I watched my chance and came out at the break of the poop on to the deck, I caught my last glimpse of old Cassey.

Either the death of the Rajah, or the sight of that great big comfortable steamer going the right way, or the two events combined, served to cast a gloom over the ship. Furthermore, there were not now enough men on deck to handle the ship properly. We had only five men in each watch, and these, with three apprentices and the mate, made up a total of nine hands in each watch to man a fairly big barque in the worst of weather.

Of these nine hands one was required at the wheel and sometimes two; another man was on the lookout forward, though it always seemed to me absurd to waste an able-

When all plain sail was set, we carried twenty-

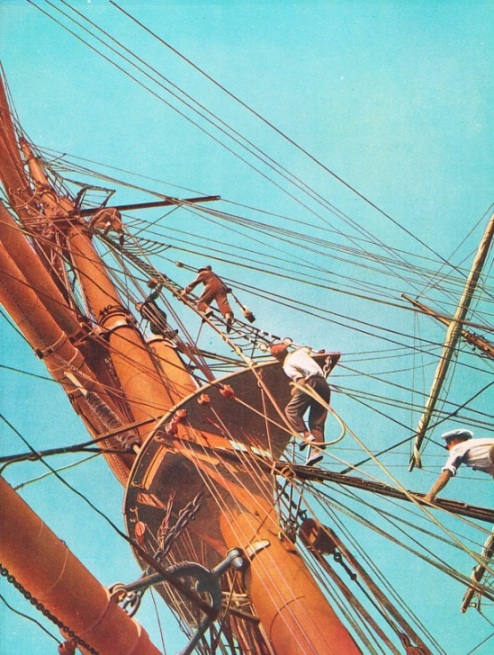

GOING ALOFT on board the Archibald Russell, one of the famous square-

To turn out at midnight in wet oilskins after little or no sleep in a wet bunk, and to go up on to the poop and take over the wheel was no joke. There was some sort of a weather cloth abaft of the wheel, designed to keep some of the icy wind off the man at the wheel. I believe, also, that its purpose was to prevent the helmsman from looking over his shoulder and seeing the big seas coming up astern. A watch at the wheel was an anxious and harrowing time. The utmost care was required.

In daylight you could see what you were doing, but on a pitch dark nigh-

I remember one night which was pitch dark. A heavy squall was coming down on us from the weather side. The mate, who was standing alongside of me, was evidently anxious. “Keep her well up”, he warned me, and to the best of my ability I kept her well up. The flapping of the sail must have wakened the Old Man, who was asleep down in his cabin.

Down came the squall with the suddenness of a thunderclap, and up came the Old Man. His white whiskers appeared in the gloom of the companionway. I had my eye fixed on that weather leech, keeping the ship well up to the wind, a rather risky situation, since, with a slight shift in the wind or a slight error on my part, she would have been caught all aback.

Although a moment earlier he had been asleep in his bunk, the Old Man sized up the situation instantly. He was a wonderful seaman. By instinct, he saw that the mate had given me the wrong order — to keep her up to it. Better to let her have the full benefit of the wind, even if she was lying half a point or so off her course.

“Let her have it!” he called out, and I let her have it. I eased her off a point, the sails filled, and away she went snoring through the water, roaring through the inky darkness with the lee bulwarks in a smother of foam.

Cape Stiff’s Second Victim

She was no flier, this good barque of Aberdeen, but that night, with the wind on her quarter, she tore along at a good 14 knots. The speed was afterwards certified to by the mate who brought up one of the apprentices with him to heave the log.

It looked as though the worst were over, but old Cape Stiff was not done with us yet. He meant to have one more victim, and that the smallest and youngest of us — the junior apprentice, whom we all knew as “Tommy”. With the coming of a fair wind, the Old Man ordered the top-

Nobody knows what happened, but there is no doubt that Tommy, while on the lee side of the yard, missed his grasp and fell. He had his oilskins and seaboots on. The sea was running high, and there was no question of getting out a boat. Some minutes, too, elapsed before anybody realized what had happened.

The ship was brought to, but by that time she must have been a mile or more past the spot where the youngster had gone overboard. The Old Man was in a terrible predicament. He made a show of searching, but he, and we, knew that there was nothing to be done.

A little later the barque was put on her course again, and off we went. With daylight, the murk overhead cleared away and a pale, watery sun appeared low on the horizon. The wind drew aft, and away we went. Later in the day the cook got into the galley and we had our first hot drink and meal.

When we arrived in port some weeks later there was nothing to be done except to lash up and hand Tommy’s sea-

DECKS AWASH IN A SQUALL, a view forward from the mainmast of the Invercauld. This photograph shows the type of weather which constantly besets a sailing ship when rounding the Horn. The sea is scarcely ever calm in this region. The Invercauld and her sister ship the Inversnaid were vessels of about 1,300 tons gross, with a length of 233 feet.

You can read more on “Handling the Sailing Ship”, “In the Sailing Ships Forecastle” and “Rigs of Sailing Ships” on this website.