© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Training in Sail To-day

Those who desire it can still be trained for the sea in sailing ships, and there are a number of special ships in which voyages of instruction can be made. For certain appointments, both British and foreign, such experience in a sailing ship is compulsory

WITHIN recent years the question of training in sail or steam has become controversial, and it is sometimes difficult to approach it without raising ill-

WITHIN recent years the question of training in sail or steam has become controversial, and it is sometimes difficult to approach it without raising ill-

THE CRISTOFORO COLOMBO, which was built for the Italian navy in 1928, is one of the best-

The subject is far too technical and involved for its pros and cons to be discussed within the limits of a short chapter, but the facilities which are offered for sail training to-

Experience in sailing vessels is still insisted upon in certain services. At home there are sections of the pilotage service, especially the sea and Channel sides of the London district, for which the applicant must have had sail training. In Germany the aspirant for a mate’s ticket must have spent fifty months before the mast, of which twenty must have been in sail. Scandinavian countries also demand a period of that experience before they will grant a young officer his certificate. There are many navies, also, which favour a spell in sail. But, as the commercial sailing ship has been driven off the seas almost entirely, the greater part of all this sail training has to be obtained in special vessels, of which there are a number now at work.

Under the British flag there is at the time of writing only one ship left which qualifies as a square-

Under the Finnish flag, Captain Gustav Erikson has the biggest sailing fleet left, employed partly in the Australian grain trade, partly in bringing short timber from the Baltic to the British Isles, and partly in miscellaneous tramping service. He finds that so many youngsters are anxious to grasp one of the few opportunities of sail experience that his ships are manned almost entirely by boys and young men. Those who are anxious to serve an apprenticeship in his ship are willing to pay a considerable premium.

Under the German flag the firm of F. Laeisz of Hamburg, which formerly owned some of the finest sailing ships in the world in its Flying “P” Line of nitrate carriers, now possesses only two sailing vessels, the Padua (3,064 tons), and Priwall (3,185 tons). After having been relegated to the South Australian grain trade for a time, these two survivors are now returning to their original nitrate business. Similarly, the firm of F. A. Vinnen, which formerly vied with the Flying “P” Line for the premier place among German sailing-

Under other flags there are a certain number of old barques, schooners, brigantines and other sailing vessels, but their number is decreasing annually. Even the Grand Banks schooner fleet, so famous as a nursery for fine seamen, is declining rapidly, as the ships lost are not replaced.

Most of the sail training in former days was done in the course of commercial voyages. Nowadays the sailing ship has practically no chance of earning her living, except in one or two odd trades whose services happen to suit her well. The war of 1914-

Before the war several of the big lines had their own sail-

At the present time, therefore, with the exception of the few sailing ships already mentioned, the only chance of a merchant seaman obtaining sail experience is with the official and semi-

Continental Training Methods

Sir William Garthwaite, the owner of the Garthpool, the last big ocean-

On the Continent they are more fortunate. There are numerous sail training organizations, of which the best known is, perhaps, the Deutscher Schulschiff Verein. This was founded in 1900 by a number of leading German shipowners and merchants, particularly those from Hamburg and Bremen. It received support from practically the whole of the German Empire, and a large part of its success was due to the enthusiasm of its patron, the Hereditary Grand Duke of Oldenburg, after whose family most of its early ships were named.

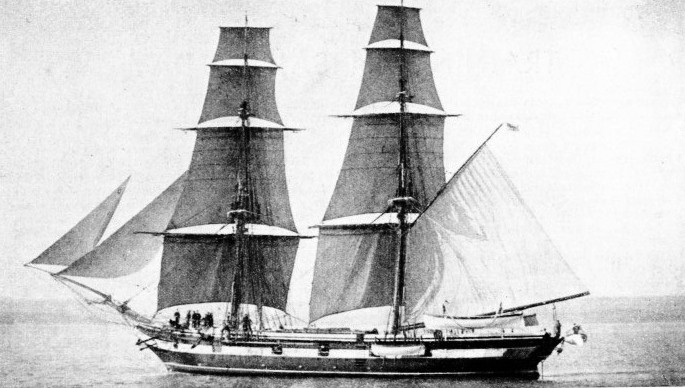

H.M.S. MARTIN, 508 tons displacement, was used as a training brig until many innovations were introduced early in the twentieth century by the late Lord Fisher. These innovations included the establishment of Osborne and Dartmouth Naval Colleges and the training together of executive officers, engineers and marines up to the rank of lieutenant. For a number of years after the general adoption of the steam engine, officers and seamen of the Royal Navy continued to undergo sail training. There are many who advocate the revival of this practice.

The Association’s first ship was the Grossherzogin Elisabeth, specially built for training. She is still in existence, although she is now permanently moored close to the Nautical School at Finkenwarder. The sea-

The handicap under which the Association works is that the fees which have to be charged prevent the signing on of any boy who is not lucky enough to possess well-

In Norway, where the Viking tradition is still strong, there are local organizations at Oslo, Bergen and other ports. These organizations train men for the Norwegian Navy -

The Oslo Training Ship Institution has for years employed the Statsraad Erichsen, a very smart little brig, of only 119 tons gross, smaller even than the Joseph Conrad, and built in 1859. At the time of writing the institution awaits the delivery of a much finer ship, 200 feet long, having auxiliary diesel engines. She is to give deep sea instruction to 100 cadets. At Bergen there is a much bigger vessel, the Statsraad Lehmkuhl, an auxiliary barque of over 1,700 tons, which was built in 1914 as the German training ship Grossherzog Friedrich August.

The finest-

When the World’s Exhibition was held at Chicago in 1933 it was Sorlandet that was chosen to represent Norway. In Sweden the Abraham Rydberg Foundation is the most important organization for training. Mr. Abraham Rydberg was a Stockholm merchant and shipowner who died in 1845. He left a large part of his fortune, including waste land (now valuable property in the heart of the City of Stockholm) to form a nautical school in the city and to give young Swedes the opportunity of a really first-

On the Australian Run

Mr. Rydberg’s foundation was a wise charity of great national importance, but it was not until about five years after this death that all the legal tangle had been unravelled and the present foundation was put on its feet with a Royal Charter. There is now a certain amount of Government control, but the work has always been carried out with such enthusiasm that there is little need of it. The foundation began work with a little brig, the Carl Johan, which was so small that her cruises were severely restricted. She was replaced by a bigger full-

In 1929 the institute bought the four-

Her crew consists of five officers, seven stewards and forty cadets between sixteen and twenty years of age, some of whom have already been to sea in steamers. The time on board consists of one voyage of from nine to eleven months, although a few cadets are permitted to stay for a second cruise. They pay a premium of about £40 a year. Although her work is somewhat hampered by laws and regulations, the ship contrives to turn out magnificent youngsters who are fully appreciated by Swedish shipowners.

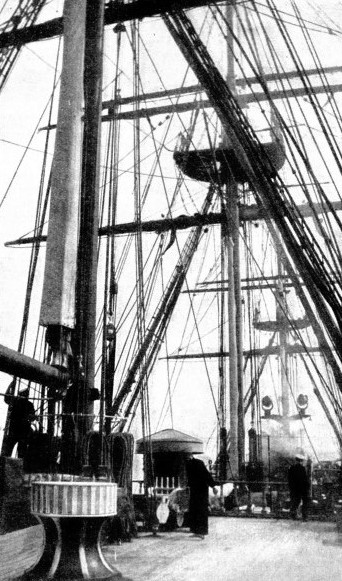

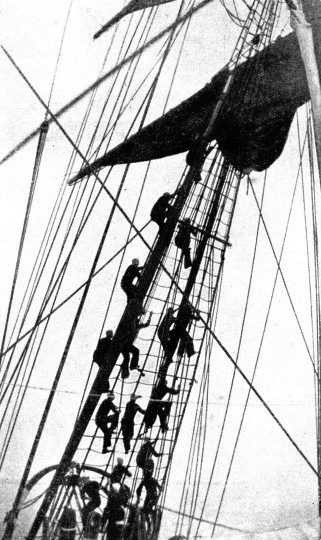

THE FORE-

In addition, a large number of Swedish lads are trained in the trading ship C. B. Pedersen, built as the Italian Emanuele Accame in 1891. She takes part in the movement of South Australian grain each year, but plans her voyage for the benefit of her cadets, often being towed through the Panama Canal, so that she does not take part, in the “race”. This ship has had a varied career and has borne a number of names. Now, however, she seems to have settled down thoroughly to her training and trading service, and it would appear that her adventurous days are over.

In Denmark, another country in which the Viking tradition is strong, the work is carried out by the Danmark, a magnificent auxiliary full-

The Danmark carries out ocean voyages, but the Georg Stage, whose gross tonnage is only 298, generally limits her cruises to the Baltic and North Sea. She has accommodation for about eighty boys of from fourteen to sixteen years old.

Several of the Northern European countries have agreements with Captain Gustav Erikson to train their cadets in his ships, but the Polish Government runs the Dar Pomorza for the benefit of the merchant service rather than for the Navy. She now has an auxiliary engine. The vessel was built as the Prinzess Eitel Friedrich in Hamburg in 1909 and has a gross tonnage of 1,620. Some time after the war of 1914-

Belgian Training Ships

In Belgium, sail training is carried out under the control of the Government by a smart three-

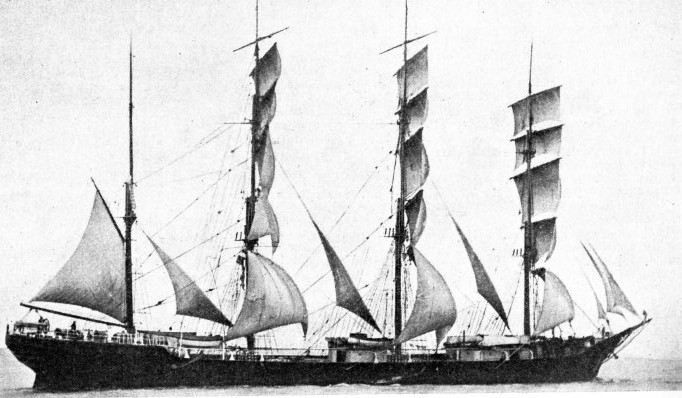

THE SWEDISH TRADING SHIP C. B. PEDERSEN was formerly the Italian Emanuele Accame. She was built in 1891, and after an adventurous career now takes part in the annual movement of South Australian grain. Her gross tonnage is 2,142. She is one of the few sailing ships to pass at times through the Panama Canal, since her voyages to and from Australia are sometimes varied to give the cadets whom she carries the widest possible experience.

The Americans have an interesting mercantile training organization. The Navy lends to the governments of the various States suitable material for training young seamen, and the States make their own arrangements. The object is to train citizens of the State free of charge; fees are demanded of outsiders. It has been found that unfortunately a large number of youngsters sign on to see the world and have no intention of following the sea as a profession. For many years the Navy lent the various States sloops dating from the ’sixties and ’seventies. These had auxiliary steam engines, but did the greater part of their cruising under sail.

When these ships first visited Britain, British sailors were full of enthusiasm for them. They pointed out how the young American cadet could gain experience in handling a steamer, which he probably would do for the greater part of his life, while the British apprentice was forced to learn his trade in sail. Latterly the American cadet has been envied for getting much sail experience, while the British apprentice, in default of any sailing ships under the flag, has been forced to content himself with steam. Of recent years the supply of these sloops has been running out and some of the States have already been forced to use full-

But perhaps the most interesting system of mercantile sail training in the world is that of the Japanese, who maintain four magnificent vessels specially built for the purpose. Two of them are new and have been built within the last few years; these are the Nippon Maru and the Kaiwo Maru, with auxiliary diesel power. The other two, the Taisei Maru and the Shintoku Maru are older. The newer ships have a displacement of over 4,000 tons and carry seventeen officers and forty-

In naval circles opinion on sail training is as divided as it is in mercantile marine groups. For many years the Royal Navy kept to sail training both for its young officers and for its seamen, and the sight of such old ships as the Volage in the Training Squadron was not easily forgotten. For the boys’ out-

Some of the other navies, however, believe in sail training. The Swedes have the Af Chapman, built in 1888 as the British trading vessel Dunboyne. Although she is getting near the end of her days she still carries out some long cruises. She is backed by the smaller three-

Poland has a little auxiliary three-

In S outh America all the principal navies maintained sail training ships at one time. The Brazilians had the Banjamin Constant, now replaced by the Almirante Saldanha, built in England in 1933, a four-

outh America all the principal navies maintained sail training ships at one time. The Brazilians had the Banjamin Constant, now replaced by the Almirante Saldanha, built in England in 1933, a four-

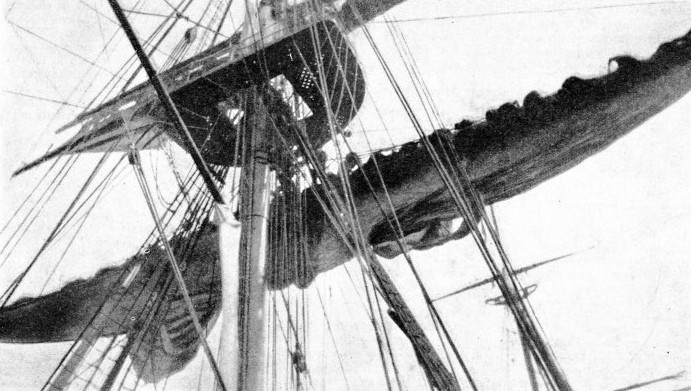

“ALOFT AND FURL IT”. This is the order for which cadets wait when they are told off to furl a sail. As soon as the order is given a race up the rigging begins, as each cadet is eager to reach the place of honour -

The Portuguese train their youngsters in the Sagres, built as the German trading vessel Rickmer Rickmers in 1896 and converted between 1924 and 1927. The Yugoslav Navy has the Jardan, the building of which was begun in Germany on reparations account and finished against ordinary payments when reparation payments lapsed. The Spanish own the Galatea, an auxiliary barque, built in 1896 as the British Glenlee, and the four-

But by far the most interesting of the naval sail training ships are the Cristoforo Colombo and Amerigo Vespucci, which were built for the Italian Navy in 1928 and 1931 respectively. Although they have the most up-

You can read more on “Auxiliary Sailing Vessels”, “In the Sailing Ship’s Forecastle” and

“The Last of the Giants” on this website.