© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

German Shipping

Crippled as Germany was by the war of 1914-

SEA TRANSPORT OF THE NATIONS -

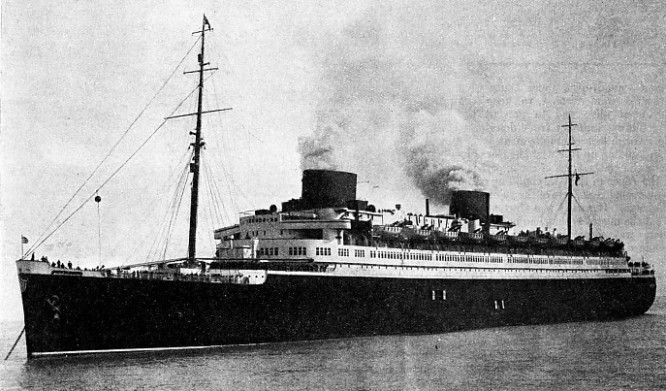

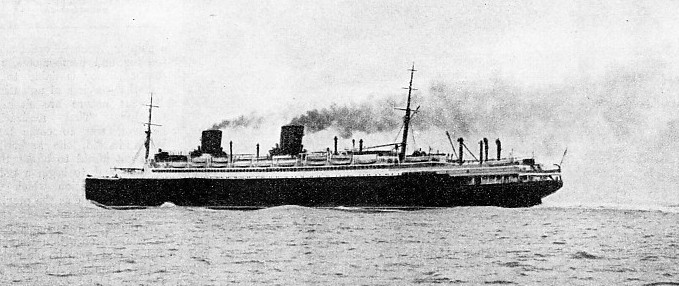

ON THE TRANSATLANTIC SERVICE, the Europa is one of the crack liners of the North German Lloyd. Her sister snip, the Bremen, wrested from the Cunard liner Mauretania the Blue Riband of the Atlantic, which she had held for twenty years. With a gross tonnage of 49,746, the Europa has a length of 888 ft. 2 in. between perpendiculars, a beam of 101 ft. 8 in. and a depth of 79 ft. 5 in. to the strength deck. Built at Bremen in 1928, the Europa differs only slightly from the Bremen of 51,656 tons gross.

THE German mercantile marine is remarkable not only for its success under an extreme measure of State control, but also for the manner in which it has revived since the war of 1914-

In 1936 German shipping climbed back to 5·8 per cent of a much larger total in the world. When so many ships are still laid up, it is even more remarkable that the German mercantile marine can claim to be one of the most up-

Under the Treaty of Versailles, Germany had to cede to the Allies all her merchant ships of 1,600 tons gross or over, half of those between 1,000 and 1,600 tons, and a quarter of the fishing fleet. She also agreed to build for the Allied and Associated Governments a maximum of 200,000 tons gross of shipping annually for three years; but this provision was waived by common consent and “reparations in kind” were-

It is now fully realized that the shipping reparations clauses in the treaty were an economic mistake. Although the German fleet was almost wiped out by them, for in 1920 it consisted of only 672,671 tons gross against 5,134,720 tons before the war, reparations spurred the country on to tremendous efforts which have had striking results.

The Allied shipowners who had taken over the German ships soon found that they had a surplus, and the slump was inevitable. Many of the vessels which were regarded as useful gradually found their way back to the German flag, but the authorities were careful that these ships, by this time getting on in years, were admitted only to a degree that would relieve immediate necessities and would not interfere in any way with the programme of new building.

The programme had been carefully thought out during the war and a scheme of Government loans drawn up. In the emergency it was necessary to modify this scheme, and little could be done before 1921; but it formed a basis and in that year 30,000,000 marks were put at the disposal of the shipowners for new tonnage. Owners and builders co-

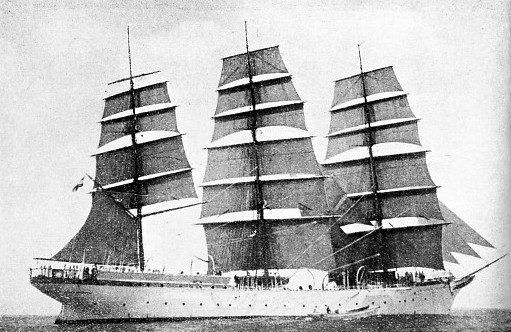

A GERMAN TRAINING SHIP, the Schulschiff Deutschland is a steel ship of 1,257 tons gross. She is one of the training ships belonging to the Deutscher Schulschiff Verein. Built in 1927 at Wesermunde, Germany, the Schulschiff Deutschland has a length of 222 ft. 8 in. between perpendiculars. Her beam is 39 ft. 1 in. and her depth 20 ft. 9 in.

The Government therefore decided to help. In two years the fleet had been almost quadrupled and successive measures were framed to keep the movement alive and to prevent the shipbuilding industry from deteriorating through lack of employment.

In building up this fleet the Germans made the greatest use of the experience of the Allies in their shipbuilding effort to overcome the effects of the submarine campaign. Germany was thus able to avoid the mistakes that had been made. There was a considerable degree of standardization wherever it would reduce building costs without handicapping the ship that was engaged in a competitive trade.

The experimental work which the German Navy had put into the diesel engine for the benefit of its U-

Different yards specialized in building different types of vessels. The naval dockyards which had been suppressed under the Treaty of Versailles were put to commercial use and the inefficient and old-

German inventors also put in an immense amount of useful effort in improving the economy of their ships in the fuel consumption of the machinery and in the improvement of hull forms. These improvements in the design of the hull reduced the resistance of the ship in the water and permitted the same results to be attained with a much smaller horse-

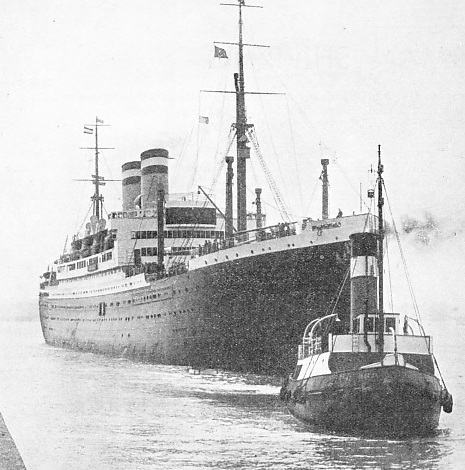

COMING INTO PORT. The Hamburg-

The much-

Among the engine-

The Bauer Wach exhaust turbine overcame the difficulty of unequal torque and permitted a low-

The policy of rationalization had succeeded admirably in the shipyards and the marine engineering works, so that it was introduced in the shipping industry in due course. Ever since Germany has had a steam merchant service there has been a tendency to group it into big concerns. The single-

It appeared at first that this would inevitably lead to greater economy, but in practice the Germans were to learn what the British had learned before, that a shipping concern can become too big and cumbersome, and that efficiency is liable to be lost when services of an entirely different nature are gathered together. That realization, however, was to come later. When it did, the authorities were not afraid to admit their mistake and to begin a policy of decentralization which was just as energetic as the previous grouping movement.

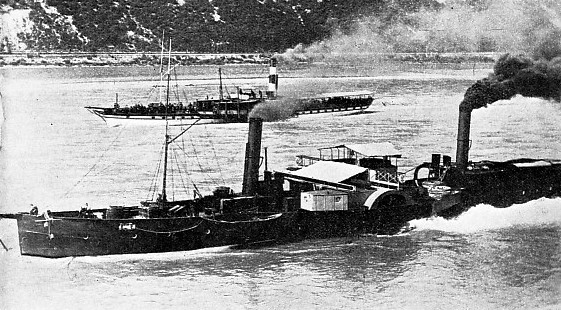

RIVER CRAFT are of varied types. In the foreground is the paddle tug Mannheim No. 1, operating on the River Rhine. These tugs tow the large Rhine barges and many of the tugs are paddle-

At the same time unnecessary cutthroat competition within Germany was abolished, and even the old rivalry between the Hamburg-

For several years the progress made in shipping and shipbuilding was a matter for the industry only. Shipping men all over the world recognized it, but the general public did not see anything remarkable. Then the North German Lloyd, repeating its daring experiment with the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse in 1897, put the merchant service in the forefront of popular interest by building the Bremen and the Europa. These ships, which are fully described in the chapter “The Bremen and the Europa”, won back the Blue Riband of the Atlantic that had been held by the Cunard liner Mauretania for the record period of twenty years.

This remarkable achievement did all that was expected. It took place in the middle of the worst slump in history, but it brought the best of the Atlantic business to the German flag, and the North German Lloyd felt the pinch less than any other company. In one year the average passenger list of the Europa numbered about 500 — roughly fifty per cent more than that of any other liner crossing the Atlantic. The slump, however, had a marked effect on the prosperity of German shipping in general. Although heavy losses were sustained by individual shareholders and workers, the owners co-

Large numbers of the surrendered ships, built before the war and bought back from the Allies, were ruthlessly scrapped. When the Government encouraged the building of new and up-

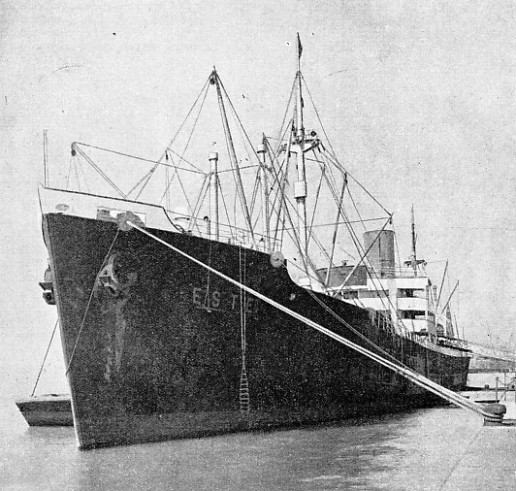

BERTHED AT SOUTHAMPTON, the Este is a German vessel of 7,915 tons gross. She is a North German Lloyd cargo liner with a cruiser stern. Registered at Bremen, where she was built in 1930, the Este has a length of 495 ft. 8 in., a beam of 63 ft. 11 in. and a depth of 28 ft. 11 in.

So the German merchant service today is a remarkably efficient organization. There are few ships laid up for lack of employment, although, as in every other country, they have to accept terms which leave little balance after the expenses have been paid, even with the financial assistance that is allowed by the Government.

Although the Germans have been active in improving ship types within the last few years, there have been no great changes in their appearance. Modern German ships have not been given square funnels, as some of the big French motorshi ps have, nor any exaggeration such as is to be found in many vessels of other countries. In the same way as the British, the average German merchant vessel gives an impression of solid efficiency that is not deceptive. The commerce of the country still has to contend with big difficulties, but the merchant service is a well-

In the river and coastal section, Germany is to some extent handicapped by her comparatively short coast-

Within her borders, however, Germany has a wonderful system of inland waterways, natural and artificial. The River Rhine, linked to the Rivers Weser, Ems and Elbe by efficient canal systems, is one of the most important of the European inland waterways.

The River Rhine is visited by thousands of tourists, who have at their disposal one of the finest fleets of river steamers in Europe. These vary with their district and particular purpose, but they are generally paddle steamers of excellent power, as is necessary in view of the strong current of the river. They are generally fitted with a short bowsprit, to which the anchor is secured ready to be dropped instantly. Some of the most modern vessels have discontinued this feature and have also substituted a semi-

Standardization Justified

The big river tugs which tow the typical Rhine barges of enormous capacity are also exceedingly interesting. Most of them are propelled by paddles, but in many the diesel, or dieselelectric machinery has been adopted. Nowadays there are also numbers of small motor vessels capable of navigating either the river or coastal waters, similar to the familiar Dutch vessels. Under the Swastika flag is a large fleet of what in Britain would be known as “short sea traders”. They are handy-

German post-

A NORTH GERMAN LLOYD LINER of 32,565 tons gross, the Columbus was built at Danzig in 1922. She has a length of 749 ft. 7 in. between perpendiculars, a beam of 83 ft. 1 in. and a depth of 49 ft. 1 in. Steam turbines drive her twin shafts through single-

These interests soon followed the establishment of the services and an immense trade grew up. The services to Africa were soon afterwards similarly encouraged. By their excellent victualling and “hotel service ” these German lines secured a large part of the passenger trade as well, and everything was made to fit into a carefully considered and detailed plan.

It was not easy to revive this scheme immediately after the war, but at the first opportunity German services were again pushing out on the old routes, modestly at first and often in partnership with companies under Allied flags, but gradually with more self-

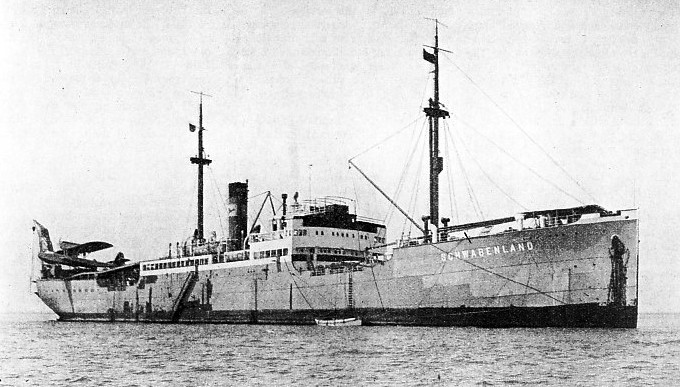

CARRYING A SEAPLANE which flies off the vessel with air-

The long-

The Hamburg-

The Woermann, Deutsche Ost-

North Atlantic Services

On the cargo side these distant services depend largely on the exportation of Germany’s manufactured goods and the importation of raw materials for her factories. They also do a certain amount of carrying trade for foreign merchants. On the passenger side a large proportion of their business comes from abroad. The ports of call in Great Britain and other countries are generally fully justified by the numbers of passengers picked up there.

Although it is not of the same real importance to the prosperity of the country as the long-

As figureheads of the Western Ocean fleet the North German Lloyd’s Bremen and Europa stand by themselves, for most of the other German ships running across the Atlantic are of comparatively moderate size and speed. The majority of them are steam-

No review of German shipping is complete without mention of the training system which, as might be expected, is exceedingly thorough. There are excellent navigation schools ashore and the Deutscher Schulschiff Verein (German Training Ship Company) maintains beautiful sail training ships afloat. The technical examinations of the officers set a high standard and great care is also taken with the training of the men.

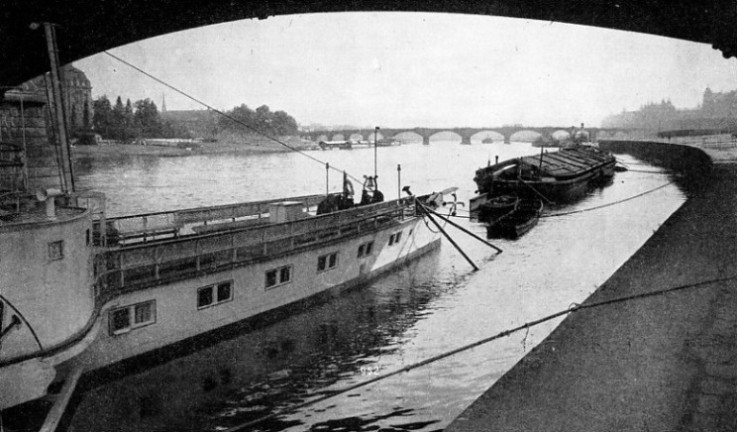

ON THE RIVER ELBE at Dresden, Germany, ply many river steamers, barges and tugs. Similar to the Rhine steamers, the paddle-

Click here to see the photogravure supplement to this article.

You can read more on “The Bremen and the Europa”, “The Kiel Canal” and

“The Svealand and Amerkiland” on this website.