© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Sailing Ships and Tugs

For many years the chief function of the steam tug was to tow sailing vessels in and out of port at the end of their long voyages. Competition was keen and the tug skipper had many devices for obtaining business desired by his rivals

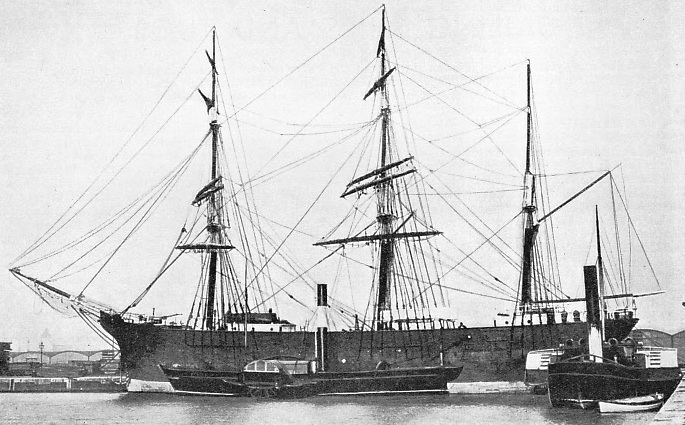

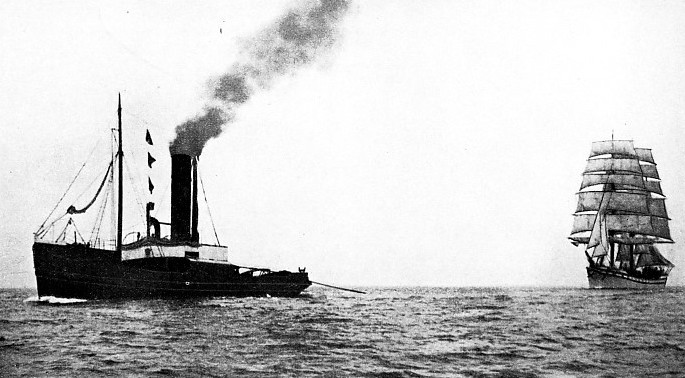

BARGAINING FOR A TOW was often conducted by shouting across the water. No written agreement was concluded, but the terms of the agreement were strictly observed. The barque Lingard (above) was built at Arendal, Norway, in 1893, and has a gross tonnage of 1019. She has a length of 213 feet, a beam of 34 feet and a depth of 17 ft. 8 in. In 1936 she was condemned to be broken up after a collision, but she was bought and re-

ONE of the most interesting phases of the sailing ship era, and one about which comparatively little has been written, is the manner in which the tug helped the sailing vessel. This was for many years the greater part of the tug’s employment. Steamers were not then so big that they required the assistance of several tugs to get alongside their berths or into their docks. Competition, however, was sufficiently severe to make it impossible for the sailing vessel to find profitable employment if days were wasted at either end of her voyage.

The function of towing sailing vessels was the purpose of most of the earliest steamboat inventions, but it was not until well into the second decade of the nineteenth century that the tug became really practical. For many years after that her functions were strictly limited, for, as a rule, she was a tiny vessel of low power. Often she could not pull a sizeable tow over the tide, and had to anchor until the tide changed. More than one instance is recorded of the tug having run short of coal before her job was finished and having to go alongside her tow to borrow enough to keep steam up. For getting a vessel down the river until she could find a fair wind, or for moving ships in and out of dry dock when they had no crews, the pioneer tugs were useful although expensive, but it was many years before they would undertake a job of more than a few miles.

The Crimean War boom of 1854-

The owners were ready and willing to take full advantage of their opportunity, and the standard of tugs improved rapidly. They were still wooden-

About this time began the custom of fitting tugs with two boilers, generally side by side with the two funnels placed abreast (“twins”) abaft the paddle wheels, but the clipper stem was still almost universal and many of the tugs were given finely carved figureheads under their short bowsprits. The tugs were all fitted with a certain amount of sail so that they might economize in coal whenever they were not towing. Such tugs were built to take advantage of the trade in the river, but as they were available it became usual for the sailing vessels on Government service to employ the help of tugs as far as the Downs instead of hanging about the lower reaches until the wind was favourable.

A London River pilot named Richard Ross, who owned a tug or two as a speculation in partnership with a syndicate, inaugurated this practice. When his tugs were as far down Channel as the Downs they would look about for the job of towing a sailing vessel back to London. There were generally a few sailing ships anchored in the Downs or off the North Foreland waiting for a fair wind. With freights booming they were willing to spend the money on steam assistance and Ross soon developed a considerable business, which was immediately copied by rival owners, with more and better boats at their disposal. Soon the competition was keen, prices were cut and all the new tugs made a practice of going to the Downs.

After the boom that had accompanied the Crimean War the sailing ships found that their chances of profitable employment were greatly decreased by the number of steamers which had been

built to take advantage of the Government employment and which were competing with them for every ton of cargo which was offered in the slump. It therefore became more and more important that they should not waste time at the end of their journey, where foul winds were most likely to handicap them. This tug assistance to and from the Downs became general.

“Taking Steam Down Channel”

Other ports began to build up a similar tug service to some point as convenient to them as the Downs were to London. The distance was never great because the boilers of the tugs ate coal, and if they went too far away from home they would not have enough fuel left to perform the tow. The London service was the most important of all, for the sailing clippers were still thriving on the Australian gold rush. Outward-

All the sailing advertisements of the better-

That started the keenest competition. Although the outward-

WAITING FOR THE TIDE in Belfast Docks. The barque Wenona is to be towed out to sea by the paddle tugs Ranger (alongside) and Protector (astern). The Wenona, 530 tons gross, was 148 ft. 11 in. long, with a beam of 34 ft. 6 in. and a depth of 13 ft. 2 in. She was built at Canning, Nova Scotia, in 1882. The old paddle tug Protector, 89 tons gross, was built in 1869.

All the early tugs engaged in this work in the ’fifties and ’sixties, and for some time after the screw tug had gained a footing on the rivers, were paddle-

The paddle tugs were far more extravagant in fuel, and they could not put their power to the same effect as the screw boat, but for many years the sailing ship master preferred them. This encouraged the owners of some poor tugs, “toshers” the sailor called them, to go in for the “seeking” business as far down the English Channel as they dared venture. They found a certain amount of business.

In the first half of the ’seventies, between 1870 and 1875, the “seeking” business rose perhaps to its fullest heights, and by that time some fine paddle tugs were used, tugs which had a surprising power considering their age and which were big enough to face any sea. Salvage work, with a sailing ship driven on to a lee shore, was inevitably the natural complement of seeking. Except perhaps for the few really long ocean tows which were then to be had, seeking and its attendant salvage were the ambition of every tug skipper who was promoted after he had learned his craft on the river or in port, working on the small sailing vessels or as “second boat” on the bigger ones. It was not so much the money to be earned, for most skippers drew two and a half per cent commission on the gross earnings of their boats, but the life was delightfully independent, comfortably out of touch with the owners for considerable periods, and full of interesting change.

Tactful Inattention

First there was the exciting task of finding the incoming ship, and in this the men developed an uncanny ability to recognize a vessel the moment her royals lifted themselves over the skyline. Considering how many sailing ships there were at sea, and how often they were liable to change their sails, this ability amounted almost to instinct.

The tug would generally leave port with a ship in tow, but this was all arranged in the office. It was the homeward voyage that was profitable, so the tug was not usually held up to wait for outward business. If none offered she would be hurried out just the same, and as soon as the skipper was clear of Gravesend — to take the London tugs as typical of the rest — he was almost independent. It is true that he and his owners used the telegraph to an extraordinary extent, but the wise owner — and most owners were former tug skippers themselves — knew when it was best to leave his servants alone.

One of the points on which the owner and the crew did not always see eye to eye was the matter of coal. Every tug firm had agents in the various ports all down the English Channel who could arrange the supply of coal where no definite contract existed, but the London River usually had its own hulks and its coal was much cheaper. So the boats were expected to put to sea not only with their bunkers full but also with extra coal stowed on deck until they would certainly not have been cleared by a modern official. They were appallingly uncomfortable for their people. However, these tugs nearly all had wooden bulwarks, and a well-

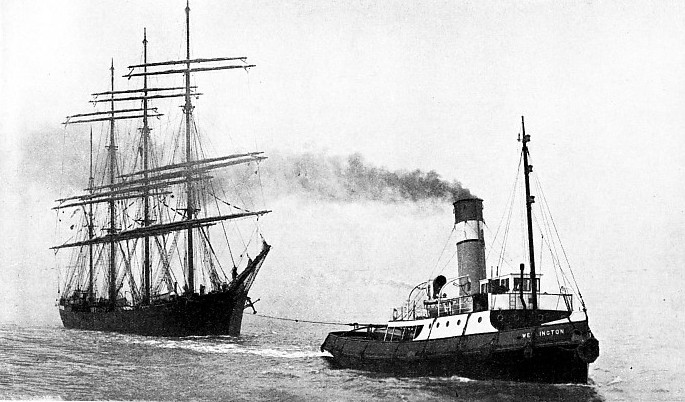

MODERN TOWAGE IN THE MERSEY. The tug Wellington, 285 tons gross, was built in 1926, and it is rare for her to tow a sailing ship. The Pommern is one of Erikson’s steel four-

Constant calls into port were useful not only for buying coal but also for getting information. The first source would be the agents, who were paid on commission and who were willing to work with other agents on a sharing basis when the information that was sent through proved profitable.

Every waterside tavern had its copy of the Shipping Gazette regularly, and the tug skippers would examine this with an expert eye. Such and such a sailing ship, a prize worth picking up by any tug, would be reported in a certain position a month previously. The English Channel made a big chessboard and the skipper had to put himself in the place of the sailing ship’s captain, with all the information that he had at his disposal. There were the force of the wind and its direction, points on which his information was naturally scrappy over the period of a month. There were the captain’s own characteristics to consider and his known predilection for doing certain things in a certain way. Every possible point had to be quietly considered over many glasses, due care being taken not to allow rival skippers to obtain any inkling. Finally it would be decided that the ship ought to be in such and such a place on such and such a day. It was astounding how often these prophecies proved correct.

Having made up his mind what ship he was going for — often enough there was nothing which seemed particularly promising, and the tugs worked entirely on speculation — the skipper’s next move was to put his plans into execution without drawing the attention of his rivals. If he had a reputation for smartness and good luck at the game this was not by any means easy. All the skippers were friendly ashore, but afloat it was different and no considerations of friendship affected the rivalry. A seeking tug’s greatest asset was a silent steam windlass which permitted her to get her anchor up and slip away from the others at night without being noticed. By dawn she would be many miles away.

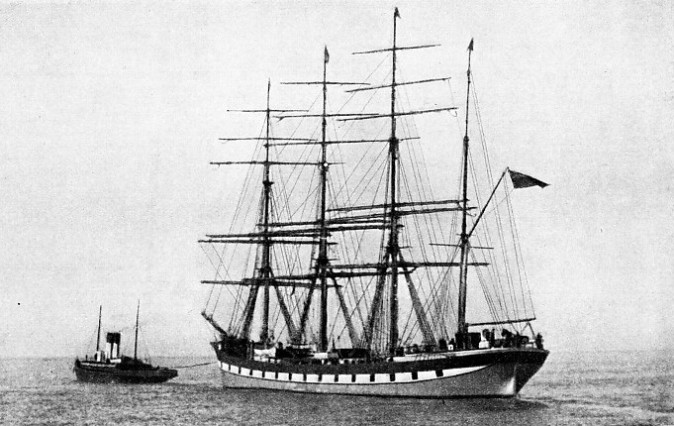

IN TORTUOUS CHANNELS and where the most complete control is necessary a short tow rope is used for towing a sailing ship. This photograph shows the four-

Often enough two tugs were struck with the same idea and would find themselves in company. Then it might be a straight race down, with the faster boat leaving her rival out of sight astern while she chose her position, but that cost precious coal and was avoided where possible. It was far better to slip down to the lower position without being noticed, and to do this the skippers did not hesitate to extinguish their navigation lights or even to reverse them on the paddle boxes, putting the masthead light on the after side of the funnel, so that at a distance she appeared to be a steamer proceeding in the other direction. It would have been a dangerous practice had not the tug men possessed such wonderful eyesight that they could pick out any other ship long before she had reached an unsafe position. So the tugs gradually worked down Channel, either in search of special objectives — which did not prevent their picking up any thing that came along — or else on pure speculation. At Deal, Dungeness, Eastbourne, Newhaven and a dozen other points along the coast a lookout had to be kept for the flag signal which called the tug in to communicate with the owner’s agent, or for the agent himself putting off in a boat with useful information. If he were sending the boat on a long job he would buy food for her crew beforehand and have it all ready for them to take over. Tug hands paid for their own food, but they did not always have much say in the choice of the menu.

If time was particularly precious the initial information would be sent out by flag signal, but as every skipper kept a keen eye on his rival’s information every owner had a secret code which complicated the matter greatly. If some of the skippers had made a private arrangement with the agent, as they often did, there was a still more secret code for different boats of the same firm.

In default of definite information most paddle tugs made the Isle of Wight the end of their seeking ground, largely to eke out their coal supplies. A sizeable fleet would often collect there. Then it was the job of every mate to go ashore at daybreak and climb to the top of the high land above Ventnor with a pair of binoculars to see if there was any sign of a sailing ship coming up Channel. Daybreak was also liable to reveal that one or two of the tugs had left the fleet and had slipped farther down Channel, sometimes inside the island to avoid detection.

Few of the skippers had any sort of a certificate, but they would often take their tugs clear of the Scillies with perfect confidence, and as coal economy was improved the London tugs would even work right down to the south-

All the competition and the tricks, however, lasted only until the tug made contact with the sailing ship. Once she had done that nobody else interfered unless she had failed absolutely to strike a bargain and had sheered off in disgust. There were one or two ultra-

It was when the tug got alongside that the fun began. Newspapers, fresh vegetables and sometimes fresh bread would be passed across, far more as a gesture of good fellowship among sailors than as a bribe. If the sea were calm enough to permit the tug to go alongside without damage, the skipper would jump on board and bargain on the sailing ship’s poop, but more usually all the business details were discussed at great length across the intervening water. Either party could be conveniently deaf when a tough argument was presented, although leather lungs would make every word heard all over the two vessels, and neither side would have been prepared to back his arguments later.

Probably an agreement would be reached by compromise and the tug would manoeuvre alongside the ship to pass a heaving line across. This light line was attached to the tow rope. Nominally the sailing ship supplied the tow rope, and paid the tug if the tug’s rope were used, but in many instances the experienced tug skipper cast a critical eye over the rope offered him and preferred to tow on his own without charge. It was a peculiar way of doing business, for there was nothing written; but the verbal agreement was always scrupulously honoured by the two parties. For ships bound for London it was always to tow as far as Gravesend, if necessary with a second tug from the North Foreland. As most of the owners of seeking tugs also owned river craft, their skippers did their best to conclude an agreement for the river towing as well, although it was not always possible.

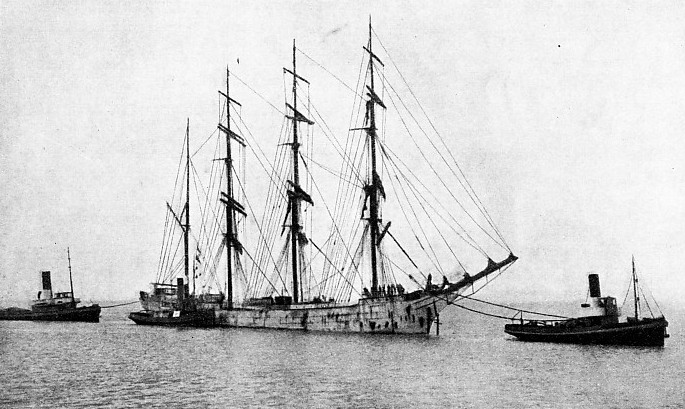

THREE TUGS manoeuvre the Hougomont into dock at Avonmouth, in the Port of Bristol. The ill-

Often the tug skipper was disappointed when he had picked up a fine sailing ship well down Channel. If the wind were westerly her captain would be tempted to carry on to Dungeness and to trust to his luck in finding a tug there at a much lower price. The skipper who had picked him up would either chase him all the way up Channel, arguing all the time, or would give up the struggle and remain on his station until another ship came along.

Many sailing ship masters overreached themselves in this way, for when they got to Dungeness they might meet a whole fleet of sailing ships all seeking the services of a few tugs who could then ask their own terms. On more than one occasion a ship had paid a bigger price to an inferior tug from Dungeness than the better boat had offered her off the Scillies.

It is not difficult to understand the disappointments for which the tug skipper had to be prepared, and the days that he had to waste in fruitless search. Instances are reported of tugs being out for weeks on end, and then not finding anything, the monotony broken only by periodical calls for coal. On the other hand, some skippers were proverbially lucky, although the luck generally went with a big measure of skill and foresight.

Having passed the tow rope, the skipper, who had probably been spending weeks with no more sleep than an occasional “cat-

Tug Acts as Sea Anchor

The operation was not at all easy on either side, for if the ship did not follow the tug she might “get her girded”, that is to say, pull her round at right angles to her course, or she might overrun or capsize her. The tug’s people had to be equally careful not to put too sudden or great a strain on to the tow rope or it would snap, possibly with dangerous results.

If the weather was so bad that it was impossible for the little tug to tow the big ship, she would keep her engines going slow ahead — always with an eye to the coal supply — and act as a sea anchor.

The screw tug for down-

Seeking for sailing ships continued, although on a steadily reducing scale, until 1914. Then the enormous number of tugs which were taken up for miscellaneous Government service made the business unprofitable and soon afterwards such sailing ships as continued to run always made a point of calling in at one of the westerly ports for orders.

The surviving sailing ships of the South Australian grain fleet continue to do that and it is easy enough for their brokers in London to make the necessary arrangements with the tug-

A LONG TOW ROPE was used for towing sailing ships in the open sea. This photograph shows the Director Gerling of Antwerp towing the French barque Cambronne, which in 1917 was captured by the mystery sailing ship Seeadler. The Director Gerling, 166 tons gross and 36 tons net, was built at Hull in 1892 with a length of 116 feet, a beam of 22 feet and a depth of 11 ft. 5 in.

Click here to see the photogravure supplement to this article.

You can read more on “In the Sailing Ships Forecastle”, “Rigs of Sailing Ships” and

“Training in Sail To-