© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

The Glory is Departed

Beneath the dirty paint of many hulks to be seen in various parts of the world are concealed the beautiful lines of proud sailing ships that were once undisputed mistresses of the seven seas

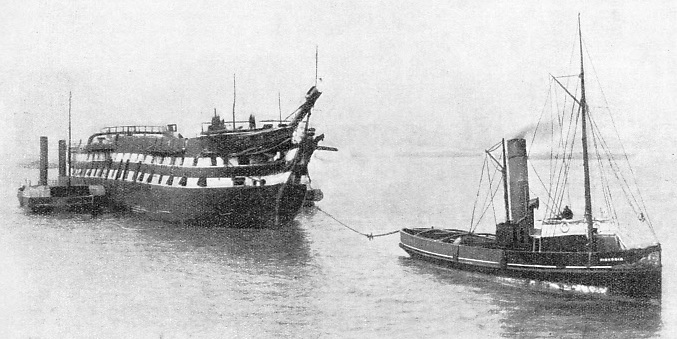

TOWED TO HER LAST BERTH, HMS Grampian, an 81-

THE old sailing ship meant so much to the men who served in her that her end was of as much concern to them as if she were one of their own kin. It is difficult for the landsman to realize the feelings of the sailor when his old ship, especially if she were a crack vessel whose reputation went all over the world, came to an end which he considered to be unworthy of her. His feelings towards her were so complex that it was often hard for him to decide how he would prefer her to finish her days.

The most fitting end to a fine ship was, perhaps, to founder or be burned at sea. Anything was better than that she should be deposed from her position and exhibited to the world degraded, a shadow of her former self which only a sailor’s eye could identify. Next to a total disappearance, being broken up while still in first-

The sailor would recognize the former proud beauty in the timber drogher or the coolie ship. The days of her prime were naturally brought back to his mind, but often enough he felt reluctant to refer to them? But the attraction of the old times was always there, and often the seaman would tramp for miles to feast his eyes on delicate lines and beauty concealed under the clotted paint and dirt.

Often, also, the officers of a ship entering a foreign or Colonial port would examine affectionately the hulks that they passed. In Gibraltar, especially, and in many of the ports in Australia, there are still some magnificent sailing ships to be seen. The lines of their hulls cannot be disguised, although their tapering spars have long disappeared, their bowsprits have been cut off short, their figureheads have gone in many instances, and their decks have been cluttered up with winches, cranes and houses required for their present work.

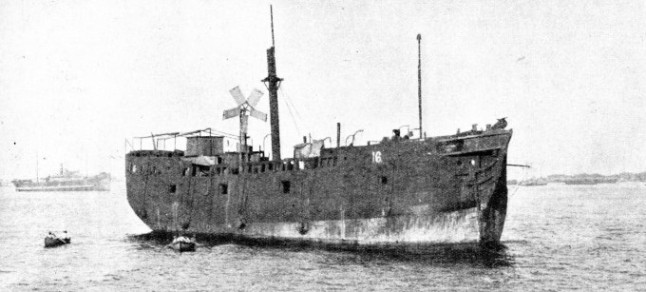

It is extraordinary to think that a unit of the old East India Company’s fleet was still in existence in 1936; yet any number of sailors know the old hulk Java, in Gibraltar Bay, although she has not carried any coal for some years past. She was one of the beautifully made teak ships built in India, and was launched from the yard of Blackmore and Company, of Howrah (opposite Calcutta), in 1811, during the Napoleonic wars.

At that time the Navigation Acts treated India almost as a foreign country, and ships built there could not be given British registry, or trade with the mother country, without special permission. But the French privateers were taking such a toll of British shipping that the authorities were grateful for anything that would float. In 1813 the Java was admitted to British registry in the service of the East India Company. She had an unusually long active life for an East Indiaman, remaining on this service until 1827. After that she had many years of trading all over the Seven Seas before she finally became a hulk.

Many other ships have ended their days in the humble capacity of hulk. When she was built at the East India Company’s own dockyard at Bombay the Earl of Balcarres, of 1,417 tons, mounting twenty-

Among innumerable other hulks which come to mind are the Blackwall frigates La Hogue and Agamemnon, cracks of their day which finished as hulks at Madeira and in Australia. The Sobraon was classed with the Thermopylae and Cutty Sark when she was in her prime on the Australian trade in the 1870s. She was bought as a reformatory ship for young larrikins — the Australian name for hooligans — in New South Wales, became a naval training ship, and was finally used as a barracks for unemployed.

In New Zealand the Edwin Fox, another “country ship” built in India and given the picturesque stern windows, decoration and poop rail of a former day, is still to be seen. After having been on the Indian run she was sold into the New Zealand trade, carrying emigrants. When she was finally disrated from that it was found that the teak which had been worked into her hull and the craftsmanship of the Indian shipwrights had lasted so well that she was still far too good to waste. So she took her part in the earliest development of the trade which was to make the prosperity of the Dominion of New Zealand — the frozen meat trade.

Stripped of her rig, with nothing but a little mast stepped amidships to act as a samson post (pillar) for her derrick, she was fitted with somewhat primitive refrigerating machinery and was used

tor freezing down the meat and storing it until the ships which were to take it to England were ready to receive it.

The Edwin Fox carried out that duty for several years, until the New Zealand meat industry had outgrown such methods. She was then, still staunch and tight, converted into a hulk for stores, and finally into a landing-

Another well-

The noteworthy sailing ships which were finally converted into hulks are innumerable. The pioneer Orient, the unlucky Samuel Plimsoll, the lofty Tyburnia and dozens of other names come to the mind, each with its touch of sadness in the comparison. After all, however, the role of hulk, lowly as it is and generally involving ugliness, is at least useful, and the old ships may well console themselves that they are serving a purpose to the last and helping their successors to find their living on the waters.

East Indiaman as Dry Dock

Useful also, although not romantic, was the end of the East Indiaman Canton, another crack ship of her day. Built on the London River in 1790, she was a ship of just over 1,200 tons, mounting thirty-

But she had plenty of work left in her for owners who were not so particular as “John Company”, and she ran steadily from 1811 until 1829. She might have continued to run then, for the old Thames shipbuilders put in some magnificent work, but there was a shipping slump at the time and her owners were willing to take £562 for her from Mr. Joseph Fletcher.

Mr. Fletcher had recently bought a site at Limehouse for the building of a repair yard which was going to take advantage of the growing possibilities of the London River when shipping revived. When he obtained possession it was to find that his site had at one time been a breach in the banks of the river. He thus had great difficulty in finding a sound bottom for the foundations of his proposed dry dock, which was to be of small dimensions. So he bought the Canton, excavated a site and scuttled her stout hull in it, cutting off one end and fitting it with a watertight caisson.

From 1829 until 1898 this old ship formed an efficient dry dock, her stout timbers remaining in such good condition that when it became necessary to replace her by a much bigger dock on more modern lines her demolition involved hard work.

Somewhat similar was the fate of the James Baines, one of the famous extreme clippers built by Donald McKay of Boston for James Baines and Company, of Liverpool, in 1854. This was at the height of the Australian gold rush, when the business justified the acquisition of some of the finest American ships. She had been on service for only four years, and had gained a great reputation as one of the fastest sailing ships known, when she caught fire in Huskisson Dock, Liverpool. Ship and cargo were valued at £170,000.

In a short time the James Baines was blazing from stem to stern. Nothing could be saved; the only thing to do was to scuttle the ship for the sake of other vessels in the dock. Although she was afterwards refloated and sold by auction for £1,080 to a speculator who thought of rebuilding her, that proved to be impossible and she ended her days, completely hidden, as a pontoon under the old passenger stage at Liverpool which preceded the Prince’s Stage of to-

At Stenhouse Bay, South Australia, about eighty miles from Port Adelaide, the loading berth of the Waratah Gypsum Company is protected by what was once a sailing ship, lying scuttled with her decks only just above high water. It is the old Hougomont, one of the best known of the later generation of sailing ships. Built on the Clyde in 1897, she was a steel four-

In 1932 she was outward-

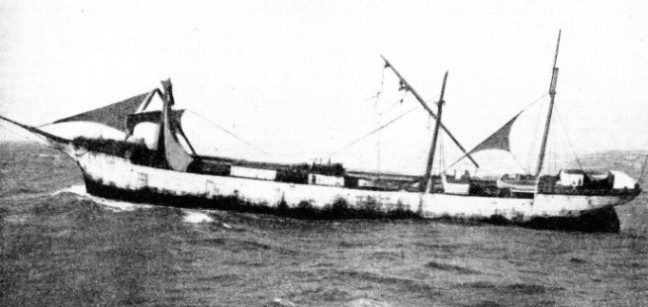

UNDER JURY RIG, after a gale in 1932, the Hougomont was sailed to her destination. Her mainmast went, and also her foremast and mizen over the tops. A small squaresail and a staysail were set on the foremast, a squaresail on the mizen, and on the jigger a staysail and triangular spanker. Unfortunately, the Hougomont was not fit to be repaired and was sunk to form a breakwater at Stenhouse Bay, South Australia.

There was every justification for abandoning the ship, but Captain Lindholm and his young crew not only determined to get her into port but also to do it without involving their owner in a heavy claim for salvage which the trade was in no condition to stand. The mainmast had disappeared altogether; the foremast and mizen had gone just over the tops, but the jigger had a fair length of topmast remaining. A small squaresail and a staysail were set on the foremast, a squaresail on the

mizen, and on the jigger a staystail and triangular spanker. With this jury rig, the wind being fair, they sailed her into Adelaide, refusing all offers of help from passing steamers and asking only to be reported so that their owner’s anxiety might be allayed.

Re-

Convict Transports

To a people as ship-

In the bad old days of the transportation of convicts the work was done by chartered vessels and the Government did not believe in paying a penny more for them than was absolutely necessary. The transportees, a large proportion of whom would have been let off with a fine nowadays or never prosecuted at all, were thus put to much unnecessary hardship, and many a fine ship, especially a former East Indiaman, ended her days in that degrading business. There was one ship which for many years was believed to be a convict ship when she was nothing of the sort. There are many who remember the old Success being exhibited all round the British coast some years before the war of 1914-

The Success was not, however, a former East Indiaman built in 1790, but was an ordinary “country” trading ship of rather unusually fine description built at Moulmein (Burma) in 1840, a fully rigged ship with teak hull and tonnage of 621. She was employed on the Australian emigrant trade, and in 1852, with five other vessels, was bought by one of the Australian State Governments to house week-

As bad a trade as the transport of convicts was the transport of coolies from Asia to various parts where labour was badly needed. At one time this coolie transport was mainly to the Chincha Islands (off Peru), where the guano workings were always short of men. One or two companies later carried coolies to the West Indies with extraordinary humanity and care, but when the trade was principally to the Chincha Islands the conditions were frankly deplorable and the coolie labourers, free men who had undertaken to work for a given period, were treated worse than criminals.

As so often happened with the slave trade, or something nearly akin to it, the worst features were largely due to the victims’ own countrymen. The slave traders on the west coast of Africa always got their supplies from the native chiefs, prisoners of war or of raids. It was the same in China. Large numbers of coolie labourers were secured by Chinese crimps in the interior, generally on the understanding that they were going to the goldfields of California or Australia.

Ten dollars head money was paid to the crimps on every recruit, and if there were the least sign of disorder or mutiny on board — even homesickness could be construed as mutinous sullenness by a dishonest interpreter — the captain considered himself justified in taking the strongest measures for the safety of the ship. A clipper under 200 feet long, with the finest lines which reduced the capacity of her holds, would be packed with seven hundred coolies as a matter of normal routine, so that conditions were always appalling. Many beautiful clippers were employed on this terrible trade.

The most conspicuous and best-

The Coolie Trade

The captain and officers drove the Chinese below with their revolvers, killing a number, and in the fight the coolies, either deliberately or accidentally, set light to the ship. Perhaps the idea was to force the officers to take off the hatches, but instead they pumped water through small holes in them. This was of little or no help in putting out the fire and in a short time the beautiful old ship was blazing, whereupon her people, mostly Portuguese, abandoned her and left the coolies to their fate.

This terrible incident was reported at the time in a number of papers, the authority being an Irishman in the crew who was one of the lucky party to reach Manila, but it is only fair to state that there are many who believe that the story was unfounded, and that the ship foundered in a typhoon. She was such a beautiful vessel that we would certainly like to believe that, but there is no doubt that many lovely ships ended their days in the coolie trade.

In some ways, perhaps, the coolie trade was even worse than the slave trade. That at least was reasonably straightforward in its operations, unsavoury as those operations were, and in the nineteenth century many a fine ship was degraded to it, the speed of the clipper being the natural consideration. Slaves were still regarded as “perishable cargo”, as they had been in Elizabeth’s day, and, in addition, the various Navies, especially the British, were maintaining ships on the preventive service which required all a clipper’s speed to evade. Many of the slavers were specially built, but many others had started in an honest trade.

Of these ships, perhaps the best known is the Nightingale. She was a clipper pursued by ill luck, but one of the most beautiful of the type built. She hailed from Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and was built in 1851 with the finest accommodation ever put into a clipper. That was the year of the Great Exhibition in Hyde Park, and her owners not only planned to use her to carry visitors across the Atlantic to London, but also to keep her in the Thames as a floating hotel for her passengers and to exhibit her to Londoners as the last word of American ship contruction. She was named after Jenny Lind the singer, “the Swedish Nightingale”, and she carried a beautifully carved portrait of that lady as her figurehead.

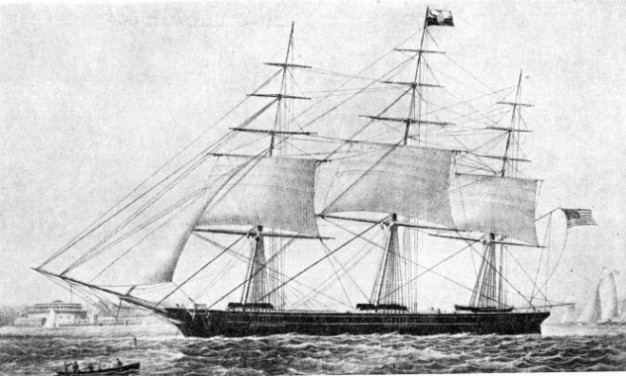

A CLIPPER WITH A VARIED CAREER. The Nightingale, 657 tons gross, was built in 1851 with the finest accommodation ever put into a clipper. Her owners planned to use her as a floating hotel for the Great Exhibition in London, but the scheme miscarried. She was bought by a reputable firm and had some successful years until she was used to carry 2,088 slaves from Africa to Havana. The Nightingale finished her days as a United States cruiser. She had a length of 185 feet on deck, a beam of 36 feet and a depth of 19 feet.

Unfortunately the plan miscarried and the ship was sold for what she would fetch. So beautiful was she that a reputable firm immediately bought her for 75,000 dollars (about £15,000), and for a few years she did remarkably well, clearing her original cost with the freights of a single passage.

In the late 1850s she changed hands several times. In 1860 she carried a cargo of American grain to Liverpool, but, instead of returning to the States for another cargo, her captain, a man named Bowen, who was also registered as her owner, dropped down to the west coast of Africa and shipped no fewer than 2,000 slaves for Havana, where he reckoned that they would fetch 600 dollars (£120) apiece. His reputation was so bad that immediately it was known that she was on the west coast, British and American men-

After coolie carrying and slaving it is something of a relief to turn to the various trades which, lowly as they were and sad for a first-

Under a Foreign Flag

One day in 1883 the farmers of Cavendish Beach, Prince Edward Island, Canada, who knew ships nearly as well as the average sailor, were astonished to see a big ship making straight for the beach. She resembled the famous Marco Polo in sadly bedraggled condition, but they had heard of her condemnation and would not believe that. But it was the famous flyer with a cargo of timber, sea-

Many a fine ship spent the evening of her days in the poorer tramping trades under a foreign flag. We constantly hear of sailormen discovering an old favourite, under the disguise of alien conditions. When the Portuguese Ferreira visited various ports, many a sailorman, attracted by her beautiful lines and knife-

The careful preservation of the Cutty Sark reminds us that there was a movement afoot in 1923 to preserve Donald McKay’s masterpiece, the Glory of the Seas, in the same way. After a wonderful career at sea she had been bought by a fish company in Tacoma (Washington), to be used as a cold store, her masts cut down to stumps and her deck cluttered with houses for her work. But her hull was still clearly recognizable and it would not have been difficult to re-

It was a sad end to such a ship, especially as there seemed to be such a good prospect of her being preserved.

A COAL HULK AT GIBRALTAR is all that remains of the old East Indiaman, the Java. A vessel of 1,175 tons, she was launched at Howrah. Calcutta, in 1811, and admitted to British registry in 1813 in the service of the East India Company. She was still in use as a hulk in 1936.

Click here to see the photogravure supplement to this article.

You can read more on “Last Days of Sail”, “Romance of the Racing Clippers” and “Speed Under Sail” on this website.