© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

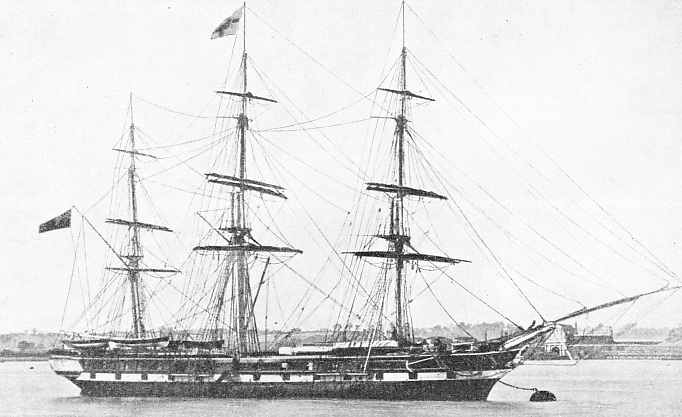

The “Marco Polo”

Foredoomed to failure in the eyes of the critics because of her ugly appearance and clumsy lines, the clipper ship “Marco Polo” proved to be one of the fastest vessels of her time

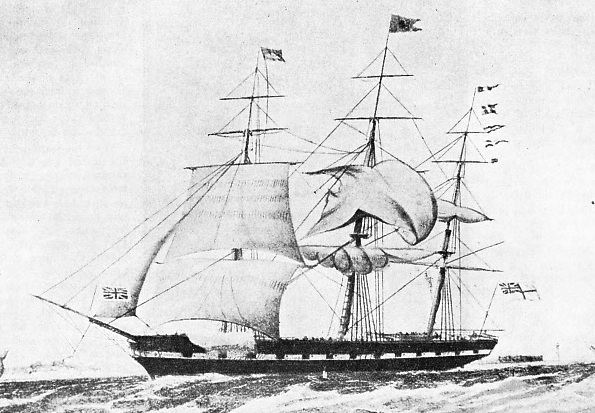

ONE OF THE UGLIEST SHIPS BUILT, the Marco Polo surprised the world with her speed. Launched at St John, New Brunswick, in 1851, she had a registered tonnage of 1,625. The Marco Polo had a length of 184 ft 1-

IN many ways the history of the clipper ship Marco Polo is the most interesting of all. She made her wonderful records when nobody expected her to, she was commanded by one of the most vividly picturesque figures in the history of sail, she opened the history of the fast clipper to the Australian goldfields, and she brought an era of prosperity to a large area of the British Empire -

Before the end of the eighteenth century Scottish craftsmen, settled in the Maritime Provinces, had started an industry for which the colony was later to become famous, the building of merchant ships on speculation for sale in Great Britain.

Sailing vessels of all sorts and sizes were built in Quebec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island. Their reputation was quite up to the average of their time, but their market was restricted and the shipbuilding industry, although valuable, employed a comparatively small number of men.

Every ship thus built was a separate venture and often much of a gamble. The materials were cheap and some of the ships so built richly deserved everything that is suggested by their popular nickname of “hard scrabble packets”, but others were remarkably well built at a time when the craftsman took a real pride in his work. Well built or ill, the routine was always the same -

The brokers knew their ships and found their buyers accordingly. Really good ships would go to firms of high standing, but in the first half of the nineteenth century the great majority were fit only for lumbering and were sold for that purpose, or for the purposes of unscrupulous owners who merely wanted to collect their insurance. These came to be shunned by the underwriters as much as by the seamen.

By 1850, therefore, the Colonial-

One of the ships built under this policy was the Beejapore, laid down on speculation by a syndicate headed by two brothers, W. and R. Wright, at St. John, New Brunswick. She was designed to be the biggest and best built ship ever attempted in the district and was to have a registered tonnage of 1,600, which was far above the average.

The Wrights’ neighbour was James Smith, and he determined to go one better, apparently principally from a feeling of jealousy. His ship was to be bigger still, with a registered tonnage of 1,625, with a length of 185 feet between perpendiculars, a beam of 38 feet and a depth of hold of 30 feet. The rule-

She was flush-

Unkind critics suggested that she was two different ships pasted together. Her builder maintained that she was designed to carry a large cargo and to sail well at the same time. The extraordinary thing is that, against all educated professional opinion she did all that her builder claimed and more. Although many ships were built as exact duplicates of her they were all utter failures and behaved just as the experts expected the Marco Polo to do.

Against her chances of success a series of mishaps was soon added to the quaintness of her original design. When the frames were erected and nearly ready for planking, the shipyard was struck by a particularly heavy gale and they were all blown down.

Speed Due to an Accident?

The vessel’s frames were set up again as quickly as possible, but the builders had no money to spare and some of the parts were built in again in a sadly battered condition. Then, when she was launched into Marsh Creek, all the precautions that were taken on account of her abnormal size were ineffective. Launched on the top of spring tides, she could not be stopped and ran into the opposite bank of the creek. There she stuck firmly in the soft mud, and when the tide ebbed she fell over on her side, giving her builder a fortnight of strenuous digging to release her. That accident caused a slight distortion of the hull, which was noticeable when she was at sea. There were many who claimed it to be the reason for her remarkable speed.

So she was sent to Liverpool with a cargo of timber and scrap iron, the freight being a secondary consideration beside the necessity of selling her for as big a price as could be obtained. It would appear that at that time even her builder was beginning to think that her critics might be right. Liverpool shipowners certainly agreed with the critics. One look at her heavy, black hull and ungainly lines was sufficient for most of them, and the fact that she had made her maiden run across in fifteen days, an excellent time, passed unnoticed.

Gold had been discovered in Australia and, on the experience of California, what the shipowner wanted was an out-

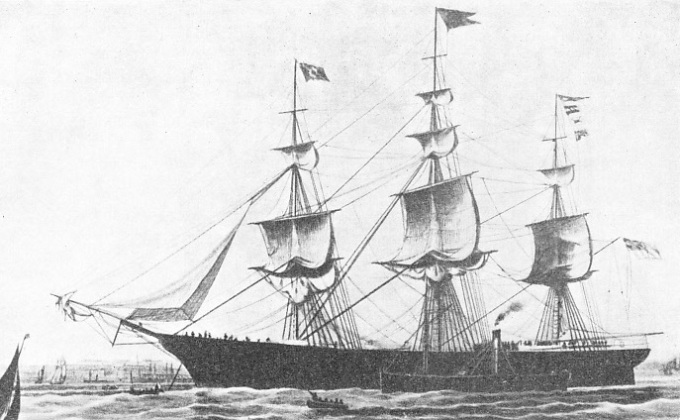

A CONSORT OF THE MARCO POLO, the James Baines was built at Boston in 1854. Of 2,275 tons, she had an overall length of 266 feet, a beam of 44 ft 9-

When she came back from Mobile her builder and his associates were in no financial condition to keep her much longer, so that a Liverpool marine store dealer named Paddy McGee, a great character even in that age of characters, picked her up for a small price. He fully realized her ugliness, but he thought that with an obvious demand for big ships starting for the Australian trade he was bound to find a buyer who did not know too much.

The buyer who eventually came along was anything but a simpleton. James Baines had seen her out of the water and he rightly calculated that, while her cumbersome upper body would give her power and the ability to hang on to her canvas long after most clippers, her fine lines under water would give her speed if she were properly handled. Baines was not a rich man, his whole capital consisting of the profits of one shrewdly managed voyage to Australia and the backing of a few friends, and his bargaining with McGee must have been noteworthy.

Eventually Baines bought her for a price which was satisfactory enough to the vendor and at the same time left the buyer with a little in hand to replace her original iron fastenings with copper and to sheath her with metal. This was a necessary operation for a fast ship, but one which was almost invariably left until the Canadian-

It was James Baines’s opinion that if she were to be successful two things were necessary -

The choice of a captain was a different proposition, for the clippers were booming on the China and the Australian trades and a first-

Captain “Bully” Forbes

Baines chose for the Marco Polo Captain James Nicol Forbes, popularly “Bully” Forbes, who had already commanded two unimportant ships on the Australian trade and had done well with them. An Aberdonian who was just over thirty when the Marco Polo was bought, he had neither money nor influence, and his apprenticeship had been a hard one. But he had real ability and an iron nerve. When he had tramped to Liverpool as a lad of eighteen these and his unlimited ambition had been his only assets. Perhaps that accounts for the bragging and bombast which marred his character later and which finally ruined him. They had been his only means of making Liverpool shipowners consider him at all. His first command was a wretched brig intended to founder; he made her do wonders and forced the shipping world to take him seriously.

Since he had taken the Marco Polo over Baines had her fitted out as an emigrant ship, but that did not usually mean any elaborate work. The first-

FLUSH-

Married couples were berthed amidships, the single women aft and the single men forward and a sound system of regulation was adopted. At that time she was the biggest ship to be considered for the Australian trade, and Baines, who in many ways was before his time as a shipowner, took full advantage of this to install reasonable ventilation in the emigrants’ quarters -

Thus equipped, she was advertised to sail from the Mersey towards the end of June 1852, but it was not until a fortnight later that she finally towed down to the Bar. A fortnight’s delay in the sailing of an Australian emigrant sailing ship was nothing out of the way and did not attract any particular attention. There was a certain amount of comment about her looks, but her size impressed Merseyside. She had a full crew, about thirty Liverpool Irishmen of the “packet rat” type, but all first-

On September 18, 1852, she arrived at Port Phillip Heads, Melbourne, after a record passage of sixty-

Running her Easting down across the Indian Ocean, when her powerful hull had the best opportunity of showing its qualities, the Marco Polo averaged 336 miles a day for four days running, her best being 364. It was a magnificent performance and could not have been done except by a fine ship; but there is no doubt that Captain Forbes’s skill had much to do with it. It was the great chance of his life and, whatever his faults may have been, he was not going to spare himself in making the most of it.

The first thing that met his eyes when the ship arrived at Hudson’s Bay was a number of ships of all descriptions lying at their anchors without crews.

The Forecastle Outwitted

Nearly forty in all, most of them had brought out emigrants to the goldfields, and the prospect of a fortune gold-

Whole crews had deserted their ships to go up to the goldfields, leaving them helplessly tied up until the seamen, disappointed of their riches, began to trickle back to the port again. Forbes was not going to have anything of that sort. A prompt interview with the police, a judicious bribe, and his whole forecastle was clapped into gaol for alleged mutiny and threatening conduct, with the understanding that they would be brought back to the ship as soon as they were wanted. One might have expected the wild Irishmen to have been furious at being tricked of their hopes of gold in that way; but, on the contrary, they treated it as a huge joke, and thought that Forbes was the greatest man alive to get to windward of them so neatly.

So the Marco Polo lost no time in landing her passengers and working out her cargo, and in little more than three weeks after her arrival at Melbourne she was outward-

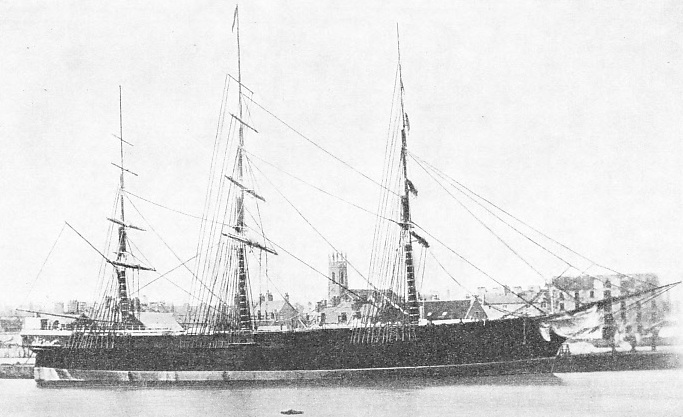

UNDER CAPTAIN “BULLY” FORBES, the Schomberg, 2,282 registered tons, sailed from Liverpool on October 6, 1855, flying the signal “Sixty days to Melbourne”. On December 27, however, she went ashore not far from Cape Otway, Victoria, Australia. She was then eighty-

With such a voyage to her credit there was no difficulty in filling up for her second passage, but her owner aimed at smaller numbers and bigger prices, and she was not packed nearly as tightly as she had been under the Government Commissioners. The passengers were mostly men of a position to afford an extra fare, and she also carried a large sum in minted gold. She arrived at Melbourne after a passage of seventy-

Her passage home was spoiled by ice, and she did not arrive in the Mersey until ninety-

Captain MacDonald ran her for the season 1853-

She retained her popularity, although she was rather unlucky in the matter of minor accidents. In 1855 a collision in the Mersey was followed by stranding, but she got off and made a good run of eighty-

Final Degradation

Considering the manner in which she was built and the materials, it was remarkable that she should have had a passenger career of almost twenty years. It was not until 1871, when James Baines was in low water, that she was transferred to J. Wilson and Company of South Shields, who bought her with the idea of running her on the coal trade to the Mediterranean. By that time she was showing her age badly and a coal cargo was about all that she was really fitted for. Fast passages were not required, but small crews emphatically were required, so she had her yards reduced and was cut down to barque rig.

In 1874 her owners became Wilson and Blain and she was chartered for a cargo of guano from South America. In 1880 she was condemned by the authorities in London as unseaworthy; but she was sold to a Tyneside firm, which spent enough money to let her scrape through a survey of sorts. Her new owners used her on the coal trade for two years and then sold her to M. J. Wilson of Liverpool for the transatlantic timber trade, the final degradation of a fine ship.

In that last chapter of her history she was so badly strained that she had to be frapped round with chains to keep her afloat, and her crew, reduced to twenty-

Finally, in July 1883, on a passage from Quebec to London with a cargo of timber, her pumps broke down and she was obviously on the point of foundering off Cape Cavendish, Prince Edward Island. Captain Bull contrived to beach her in such a position that it was possible to save the cargo which, with the wreck, was sold by auction for £600.

While the work of discharging the cargo into schooners was in progress a gale sprang up and the ship rapidly broke up. Some of her fittings were salved and her steering gear was installed in the barque Charles E. Lefurgey, a new Canadian-

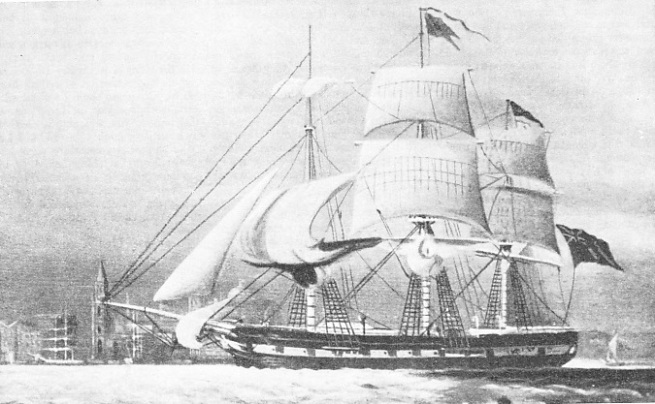

THE PIONEER BLACKWALLER of Money Wigram’s Melbourne passenger trade was the Kent, of 927 tons. She had a reputation for ghosting along in light airs, but the Marco Polo, having left Melbourne the same day in 1854, reached the Mersey only one day after the Kent had arrived at Hastings. Sussex. The Kent was 186 feet long overall and had a beam of 32 ft 6-

You can read more on “In the Sailing Ship’s Forecastle”, “Romance of the Racing Clippers” and “Speed Under Sail” on this website.