© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

A Trinity of Dramatic Exploits

The raising of three ships -

DURING THE WAR of 1914-

THE Onward was a cross-

Then, during the war of 1914-

travelling to France when she was, in fact, returning to England.

One night, after the Onward had disembarked troops on leave at Folkestone, a queer glow began to flicker up and down through her ports; a few puffs of smoke curved upward. In a short time flames and sparks were shooting to the skies and lighting up the whole quay.

The Onward was moored against the quay, whose timbers were close to her side. An immense volume of traffic was passing between Folkestone and Boulogne, and it was vitally important that nothing should interrupt it.

The officials saw the blazing vessel ejecting sparks on to the timbers of the quay, with the flames appearing out of her port-

Prompt action was needed to save the blazing Onward, but even prompter action was needed to save the quay. Hoses and fire appliances were useless at that hour. Without hesitation it was decided that the only way to save the quay as well as the ship was to sink the Onward where she lay.

A few plucky men managed to get to her sea-

But instead of sinking in a stable condition and sitting sedately upright on the bottom with her masts and funnels showing above the surface, the Onward unfortunately lost her balance and rolled over on her side. This untoward event complicated affairs for the salvage men. Had the ship been upright, part of her works would have been above the surface at low tide, and it would have been a simple matter for the men to get their powerful pumps inside her and pump her out to refloat her. The salvage men were further hampered by the fact that she had sunk so close to the quay that there was no room for them to bring lifting craft or other salvage vessels between her and the quay, to work from either side of her at the same time.

As for the authorities, once the quay was saved they were concerned only with the fact that while the Onward was lying submerged she was robbing them of a place where a vessel could berth They listened quietly while the officers of the salvage section dwelt on the difficulties of dealing with the troopship , then they issued a few orders with a final remark that was to the point. “We give you a month to get her out of the way,” said the Admiralty calmly.

There was no question after that of “if it could be done”. It had to be done; so Commodore F. H. Young, who was then in charge of the Admiralty Salvage Section, hastened to Folkestone to consult with the salvage officers, who were summoned to the spot, among them Commander G. Davis, R.N.R.

Tug-

“We’d better clear away her funnels and all her top hamper as soon as possible to prepare her for uprighting and then bring round one of the lifting vessels,” said the commodore.

He and Commander Davis gazed down on the overturned troopship. The Admiralty had set them a difficult problem, and the order to solve the problem within a month seemed a challenge to their skill. When all her top hamper was off they would be able to

get only one lifting craft moored alongside her, and this would be able to exert a pull of just over 1,000 tons on her to help her upright. This pull was one-

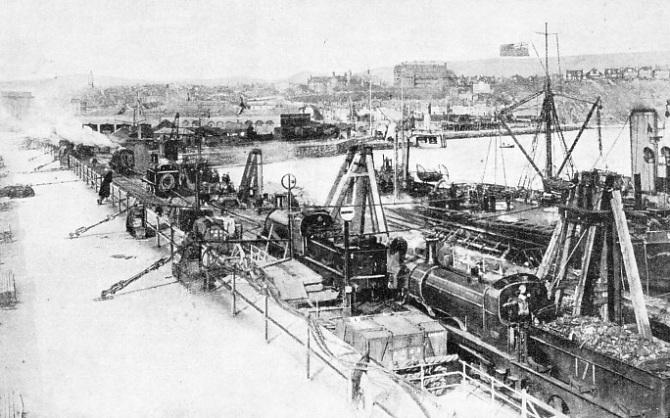

Puzzling over this knotty point. Commander Davis happened to glance at the railway tracks running along the quay. Trains needed power to move them. “Why not use locomotives?” he remarked.

It was a brilliant suggestion and one that the commodore adopted at once. A tug-

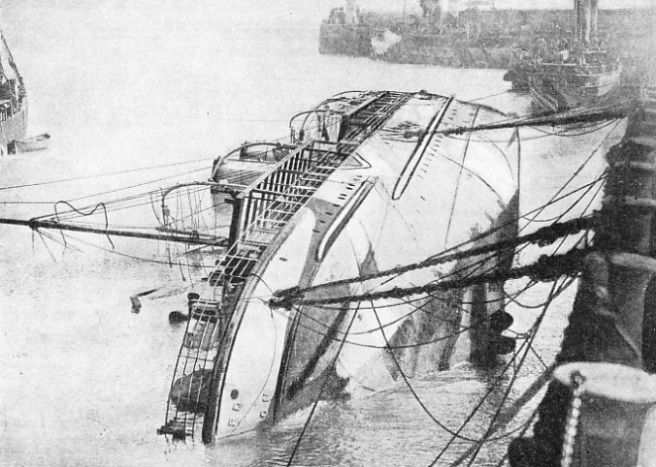

ONE MONTH ONLY WAS ALLOWED to the salvage men by the Admiralty to clear the sunken Onward away from Folkestone Harbour. This picture shows the camouflaged troopship lying on her side by the quay. The work was accomplished in less than the scheduled time; for once the locomotives and the lifting vessel had righted the Onward she was quickly pumped free of water and towed off into dock.

Squads of men set to work on the ship with their oxy-

Then divers slid down into the sea and closed the sea-

Preparations were completed, and at low tide the lifting vessel was made ready. A series of steel cables attached to the upper side of the ship was carried over her hull towards the quay, down her keel, underneath her and up on the seaward side of her, where they were fastened to the lifting vessel. As the lifting vessel moved upward with the tide she would tend to pull the Onward upright. Cables were likewise attached to the most suitable parts of the ship, carried over the tops of the massive tripods on the quay and attached to the locomotives.

As the tide rose, five locomotives stood in a line on the quay with the engine-

Disaster in the Solent

But instead of travelling along the metals at full speed with trains behind them, they were kept in the same place by the deadweight of the ship. It was a unique sight, and slowly the overturned Onward yielded to the combined power of the locomotives and the lifting craft and came over until she was nearly upright again.

The novel method was an unqualified triumph. Once the ship was on a fairly even keel the salvage men soon pumped the water out of her and towed her off to dock. They made even better time than the Admiralty allowed them, having still a day or so in hand when the job was finished.

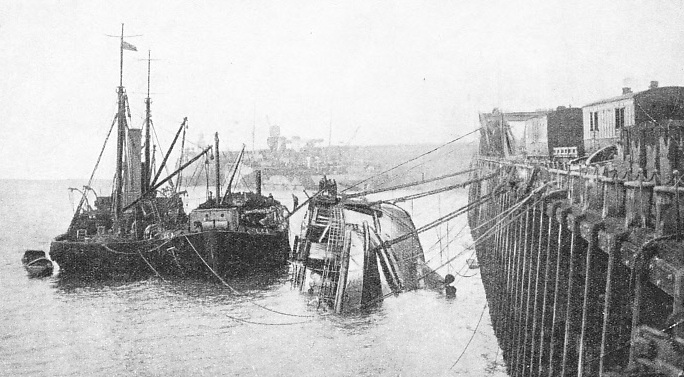

THE ONWARD OVERTURNED IN FOLKESTONE HARBOUR, with her funnels cut away and her deck houses removed. Between the Onward and the salvage steamer can be seen the lifting craft. Cables were attached to this ship and the Onward. so that as the tide rose, the Onward, also being hauled upright by the railway engines, would be gradually shifted and brought into a vertical position.

Overturned ships are always a great problem to the salvage officer, who never knows what is going to happen to them. Each provides her own special set of difficulties, the method that is suitable for one ship being perhaps impracticable for another. If a ship is not too big, the salvage officer may erect two tripods on the side of her hull, which is of course lying flat as though it were her deck, and attach ropes to the tops of her masts, which are lying on the surface. He will then carry the ropes over the tops of the tripods -

Bigger ships, however, need something more than these simple methods before they will respond. Often the salvage man has to resort to all sorts of methods before he can gain his own way. Commodore Young, who was awarded a knighthood for his salvage work, had a long and wide experience. One of the big jobs which helped to make his name as a salvage officer was the salving of the warship Gladiator.

The cruiser Gladiator was out in the Solent when the American liner St. Paul left Southampton in a blinding snowstorm on April 25, 1908, to make the run to New York. By some mischance the course of the liner converged on that of the cruiser and, because of the weather conditions, the St. Paul was unable to avoid a collision. She cut deeply into the side of the Gladiator, and although the captain of the warship did his best to beach his vessel she grounded and heeled over on her side before his effort could succeed.

The naval authorities, examining the Gladiator, consulted the Liverpool Salvage Association to see if it were possible to raise her. The association’s chief salvage officer, Captain F. H. Young, as he then was, found himself in charge of one of the most difficult salvage problems in his experience.

The naval authorities, examining the Gladiator, consulted the Liverpool Salvage Association to see if it were possible to raise her. The association’s chief salvage officer, Captain F. H. Young, as he then was, found himself in charge of one of the most difficult salvage problems in his experience.

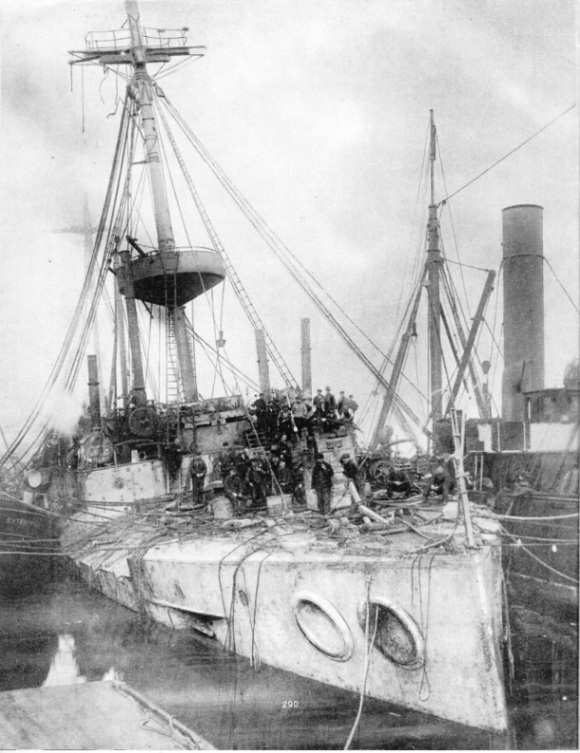

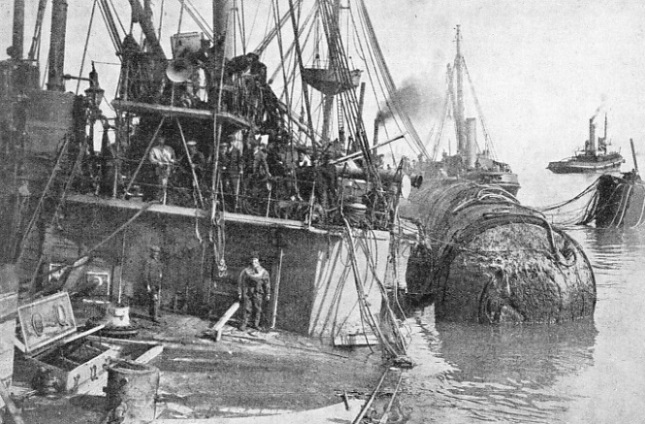

A SALVAGE TRIUMPH. The cruiser Gladiator, supported by salvage tugs, is shown after her arrival in Portsmouth Dockyard. This cruiser was rammed and sunk by an American liner, the St. Paul, in the Solent on April 25, 1908. For five months the cruiser lay on her side before the salvage experts succeeded in righting and refloating her.

As the Gladiator was a dead mass of 6,000 tons, Captain Young saw at once that the first thing to do was to remove as much of her weight as possible. A great gash in her hull, 50 feet long, showed where the bow of the liner, with an 18,000-

The divers, moving ponderously about the wreck, began their work under the sea. Other skilled men got busy with their pneumatic cutters above water, cut and chiselled away for weeks to release the guns and lift them out of the wreck. Shearing through the funnels, the men cleared them away also and removed all the deck fittings that could be reached.

The salvage officer grew anxious lest the wreck should slip down into deeper water. She was lying on a bank of hard shingle that shelved acutely, and he saw the necessity of trying to move her out of this dangerous spot and nearer to the shore. Before that could be done it was essential for the folded plates to be cut away from her open side, as otherwise they would have dug into the bottom and fixed her firmly in the one spot.

This meant work for the divers. At that point the tide was very strong, reaching at times eight knots. As a tide of two or two and a half knots is about as strong as a diver can manage to work in, the divers on the job were greatly handicapped and compelled to wait for the slack water.

Taking advantage of every minute when the tide served, they went down and fixed charges of gelignite, and then returned to the surface to wait until the charges were exploded. In this way they removed all the plates that projected from the edges of the hole.

The Gladiator’s boiler rooms were open to the sea, and nothing could be done at the moment to make her watertight there. The divers, however, put some pumps to work in other compartments to give her a little more buoyancy, so as to take her weight off the bottom. They then lashed to her two pontoons or “camels”, with a combined lift of 200 tons. After this they set up some winches in strong beds of concrete on the shore and attached steel cables to the ship. Five powerful tugs were called in to play their part and were set hauling while the steam winches ashore turned in their cables inch by inch.

It was a terrible struggle to shift the sunken warship. They had moved her only a few yards when a part of her bridge pushed into the shingle and anchored her immovably. There was no alternative but to cut away the forward bridge. This was done.

Once more the tug-

Eventually they moved the Gladiator into a better position, where they were able to work on her with greater comfort and seal up the openings in her deck with strong wooden patches. Meanwhile, the workers in the dockyard made five more giant pontoons, so that, when the time was propitious, they could add their lifting power to raise the wreck from the bottom, and help to turn her on to a level keel.

It now became plain why the salvage officer, in clearing her decks,of the guns and other obstructions, had allowed her masts to remain in place. They were destined to play an important part in the righting of the cruiser. Two tripods were erected on the hull of the vessel in a line with the masts. They were not fixed by the feet, so when the ship moved they could slip down automatically out of the way as the hull became perpendicular.

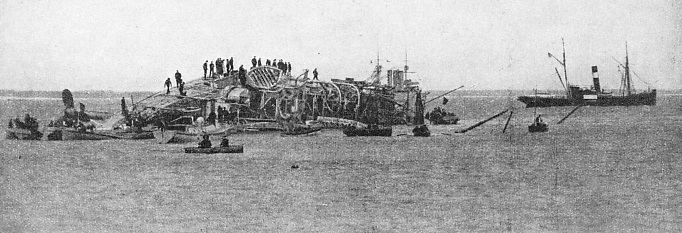

THE DAY AFTER THE COLLISION. The Gladiator, a 6,000-

Five of the pontoons were attached by the divers to the starboard side of the ship, which was in contact with the bottom. It needed much patience to get them into position, for the biggest of them was 75 feet long and 12 feet in diameter. The difficulty of handling a tank of this size from small boats and on the slippery side of the wreck can be well imagined.

One day, after weeks of hard work, two tugs picked up the ends of the steel cables running from the masts of the Gladiator and up over the top of the tripods; the propellers churned up the sea as the tugs hauled doggedly on the overturned ship. The empty pontoons strained up towards the surface, and the pumps, set up in the watertight compartments of the ship, poured forth cascades of water. On the upper side of the keel the salvage men had piled 280 tons of iron to help to press it downward. It needed this and all the other power they could apply to drag the cruiser over.

The first step towards getting her to harbour was accomplished. She still sat on the shingle with her upper deck below the surface; the salvage officer therefore determined to float her by covering her deck with a huge coffer-

baulks were carefully caulked, and five months after the Gladiator had been sunk the salvage officer set all the pumps to work, and he had the satisfaction of seeing her float once more.

NEARLY ON AN EVEN KEEL. A view of the Gladiator after she had been raised by tugs and pontoons. The largest of the pontoons used measured 75 feet long and 12 feet in diameter. The divers’ task of securing the great tanks to the lower side of the vessel resting on the ocean bed was one requiring great patience and skill.

Meanwhile, the St. Paul went her accustomed ways, carrying passengers to and fro across the Atlantic. The mortal wound she had dealt the Gladiator was forgotten, and when America came into the war the order went forth to convert the liner into a troopship for transporting the American troops to France.

Divers’ Lives Endangered

Early in 1918 she was refitted, and the tugs were jockeying her into position at her quay in New York when she began to list. The men on the tugs and on the quay could hardly believe their eyes. They saw her decks cant more and more as she heeled over, watched her masts come into contact with the quay and buckle up as if they were lily stalks. Before they could do anything she rolled over on her side and went down.

That was on April 25, 1918, exactly ten years after she had sunk the cruiser. It was a remarkable coincidence, and how she came to sink in this unexpected manner was never properly determined. A thick belt of mud lay at the bottom of the dock, and within a few minutes two thousand tons of mud had gushed through the open portholes. By the time Mr. R. E. Chapman, of the Merritt and Chapman Wrecking Company, arrived on the spot to see what was to be done, she had bedded down comfortably a dozen feet into the mud.

All the difficulties with which Commodore Young had contended in raising the Onward were here amplified tremendously. Instead of a cross-

She presented a most striking spectacle as she lay there on her hull in the dock. The shipping authorities and the salvage expert walked about her side to examine her and discuss what was to be. Done.

It needed no more than a glance to tell Mr. Chapman that, whatever method he adopted to right and raise her, it would be impossible to do anything until her funnels and masts and all other deck encumbrances had been removed. His men got to work; the salvage lighters with their derricks mounted on board made their way gingerly round one side of the ship to lift the masts and other things clear as they were cut away. The salvage men burned their way round the base of the big funnels and the masts; they cut through metal thick and thin; they stripped the long deck of the liner of every obstruction that was likely to interfere with their plan.

Then the divers were told off to go inside the ship and close all the openings they could find. To the layman the difficulties of this task can barely be appreciated. When passengers board a liner it is difficult at first for them to find their way about her. When a liner turns over everything is shot in confusion to the lowest point; the floor turns up and becomes a wall, one of the walls becomes a ceiling and the other the floor. It would appear to be impossible to find a way through this hopeless muddle while the ship is under water, so muddy that it is impossible to distinguish anything in the darkness.

This is what the divers had to do -

Formidable Obstacles

When the divers reached them they were working 50 feet below the surface of the harbour. They were completely blinded, for the mud blacked out everything.

These drawbacks, however, could not stop them. Working by touch alone, they used a powerful hose to wash the mud away from a port-

One job set them a puzzle. It was to fit a steel plate over a circular opening that had a series of seventeen bolt holes round the edge. Their problem was to get the bolt holes in the plate exactly opposite the bolt holes in the hull of the ship so that they could slip bolts through, screw them up and close the opening.

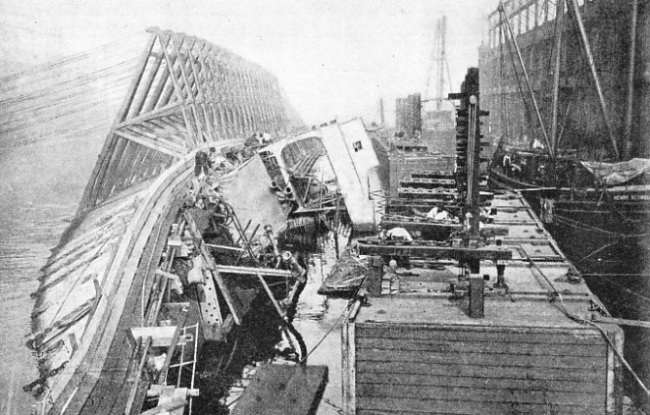

AN OVERTURNED LINER. A striking picture of the American 11,629-

Then a diver had an inspiration. Calling for a sheet of lead, he took this down with him and placed it over the opening. With a hammer he beat the lead carefully round the edges of the opening and so obtained an impression of every bolt hole with its exact size. From this lead pattern they made a steel plate, through which the bolts screwed home as easily as if the job were being done with the ship in dry dock.

The bulkheads which run across a ship and shut her off into compartments set the salvage engineer a formidable problem. It was essential for his purpose that water should be able to flow freely from one end of the ship to the other, so that he could pump her out in due course. As the bulkheads formed steel walls at intervals along the whole length of the ship, he had somehow to make a gap through them at their lowest point.

“We’ll try explosives,” he said.

The divers took down a charge, placed it in position against a bulkhead and came out of the ship while the charge was touched off. They returned to see what had happened. The explosive had made a hole, but it had seriously damaged the bulkhead. They therefore abandoned this method and eventually adopted the electric arc to burn holes through the rest of the bulkheads, under water.

This miracle was worked by electricity and gas used in combination. The end of the electric torch was shaped in the form of a cup, with a pipe at the bottom through which compressed gas was pumped down from the surface. The pressure of the gas kept the sea out of the end of the torch and reduced the water inside the cavity to steam. Right in the centre of the cup was an electric terminal, carrying current from the surface. When the end of the torch was held close to a metal plate a spark, otherwise an electric arc, was formed with the high temperature of 6,700 degrees. To look into a furnace that touches 3,000 degrees it is necessary to protect the eyes with dark glasses. The enormous temperature developed by the arc melted the metal as if it had been butter.

While the divers were toiling inside the ship, gangs of men were swarming about the hull fitting up great legs 30 feet high, shaped in the form of the letter A. They were made of steel girders, properly braced to withstand the enormous strain, and twenty-

A dredger was set to work in the next quay to cut a deep trench in the clay. Along this trench they sank twenty-

Meanwhile, along the quay the salvage men set up twenty-

Sinking pontoons and attaching them to the liner, the salvage men brought round their floating derricks and linked them up to the ship. Then they started all their steam engines working in unison on the quay, while the floating derricks hauled away and the pontoons did their best to pull up to the surface. A week passed before they succeeded in levering the ship upright.

The worst of their troubles were then over. She was, it is true, still sitting in the mud, and had to be refloated. For this purpose the salvage men enclosed the entire deck of the St. Paul in a huge coffer-

AN INGENIOUS SOLUTION. The wonderful maze of A-

You can read more on “Diving for £1,000,000”, “Dramas of Salvage” and

“The Shipbreaking Industry” on this website.