© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Fisherfolk of the Faeroes

It is the duty of the Fishery Protection Service to see that British and foreign fishing vessels abide by the regulations and restrictions governing the fishing grounds. After an offence against territorial laws, however, fishermen will often run considerable risks to avoid arrest

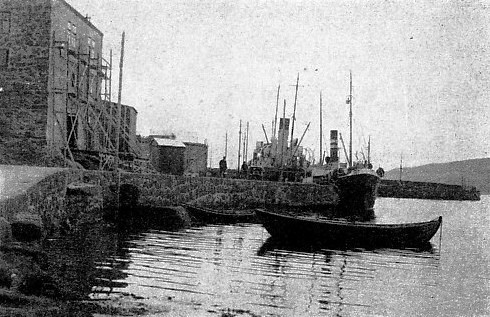

THORSHAVN HARBOUR, on the Island of Strömö, the largest of the Faeroes. A number of coastal steamers visit the port, as do the Shetland fishing smacks. Many of the Faeroes fishing fleet are registered at Thorshavn, or Torshavn, as the harbour is called in Danish.

A THOUSAND years ago the longboats of the Vikings pulled out from the cliff-

Westward they sailed, too, to the Vestmann Islands and Iceland, and beyond. Greenland and the coast of Labrador saw the slim black galleys of the sea rovers. Even to-

Their ancestors, in undecked boats with single squaresails, carried fire and sword to the prosperous villages of the south. To-

A century ago the seventeen inhabited Danish islands of the Faeroes supported a meagre population of a few thousands who eked out a bare existence by netting sea-

The fisheries are the foundation of all this new prosperity. Recently the value of dried cod and other fish exported in one year totalled over £650,000 — nearly £30 a head and ample for importing all the food the islands cannot themselves produce, and the luxuries of life.

Strangely enough, Shetland, that British Viking colony, taught the Faeroeman how to plunder the distant banks. Shetland smacks, sheltering often in Thorshavn (Torshavn), Vestmanshavn or other Faeroes ports and using them sometimes as a base, would take occasional Faeroemen as crew, until the Faeroemen themselves thought of buying and manning smacks. These boats, averaging 80 tons — little, sturdy wooden vessels, ketch-

They still bear their old names, for no Faeroeman would commit the crime of changing a ship’s name. So you may read, with a quickening of interest, the neat lettering upon the transoms, with their registration ports of Thorshavn, Vestmanna or elsewhere. Names such as Alexandra, Queen, Westward Ho! and Victory may be seen. At one time the Shetlanders sailed to the Iceland banks, and brought back not only fish, but also contraband tobacco and brandy to be smuggled into Scotland. When that ceased to be profitable, they were glad to sell out to the Faeroemen, and so the modern Viking came into his own.

In the first half of the fifteenth century the deep-

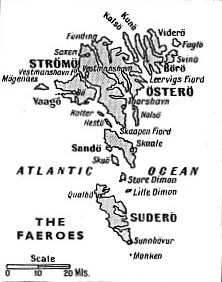

THE FAEROES are a group of Danish islands about 195 miles north-

During the war of 1914-

The war helped the Faeroes to establish themselves, and even in the depths of the world depression the islands have not suffered unduly. The cod fleet numbers more than 160 auxiliary sailing vessels, including one or two schooners of the Newfoundland type. There are besides nearly 200 motor boats and about 1,600 rowing boats.

The Faeroemen used motor boats while the first motor craft were still a curiosity in British waters. The Danes were pioneers of these small engines, and the Faeroemen, hitherto at the mercy of the wind and sea, and the swift currents and treacherous tide rips that make navigation among the islands a constant peril, adopted the new invention enthusiastically.

These little engines are noisy, but the Faeroeman has no objection to noise, and night and day in the summer months may be heard the racketing of open exhausts echoing across the bays and between the high green hills that lock the fjords.

In Shetland the fishing season lasts for little over six weeks; but in the Faeroes it extends as many months, or more. When the worst of the winter storms are past the small boats put out for the inshore hand-

They lie alongside the quays, taking in stores, and when they are ready for the sea the master, a seasoned veteran, goes on board. The men follow — the cook, who also is an old hand, and the mate, younger, but reliable; then the hand-

Among most Faeroes families it has become a tradition that every boy shall have at least one season on the Banks, whatever his subsequent career. Thus there may be future doctors, lawyers, schoolmasters, business men or builders among the twenty-

The day of sailing comes; and now a little knot of women and girls, with here and there a father, grandfather, or young brother, gathers on the quay to say farewell. They know, those people who are being left behind, what dangers their men must face. They know that disaster may overwhelm the tiny vessels at any moment, and that the long weary months of waiting will drag on with no respite for those who wait.

Some fishing communities make it a rule that not more than two members of a family will sail together. But the family is the most powerful unit in the Faeroes, and men of the same kin tend to keep together. Ships are manned by families or by crews from the same village or the same island, and when disaster comes there is stark desolation to follow.

Recently two smacks were reported by a trawler homeward-

Some years ago three men from Koltur (Kolter) were out fishing in a boat several miles from the island, when a sudden fierce storm came up. The remaining men of the island launched the largest and stoutest of their boats, to put out to the rescue. All were drowned. The island was left without a single adult male.

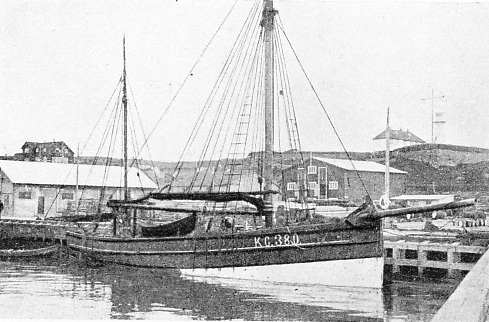

AN AUXILIARY KETCH in Thorshavn Harbour. There are more than 169 vessels of this type in the Faeroes cod-

Disasters such as these are inevitable in communities that live by the sea and on the sea. To the Viking, they are to be accepted with resignation. But it is little wonder that while the men are such magnificent sailors no Faeroes woman can feel at home on the water, and the slightest storm will make her violently ill. A subconscious terror of the sea seems to have been bred into the Viking women, for it is on them that the burden of tragedy falls. So the farewells called from shore to ship are a genuine cry from the heart.

At length our smack begins to move. Last God-

She passes through the channel between the breakwater and the rocky shore, and now her head lifts a little to the long swell, the wind fills her canvas and she begins to lean over. The swell becomes steeper, with broken foaming crests, and she pitches more and more, until she settles down to her heaving, scrunching battle with the age-

She passes out of sight, hidden by a cliff-

Clear of the islands, a course is set for the Iceland Banks, and day after day the smack trudges on, close-

Quarters are cramped. Twenty-

When they have reached the Banks the real work begins. As soon as the ship is ready, snugged down to whatever weather the North Atlantic sends against her, the lines are brought out — four lines a man. From dawn those lines are out and constantly at work. The cod come on board in a steady stream, hauled over the gunwales and killed with a single blow, until the heaving wet deck is piled with a slithering mass of fish.

Hot meals are rare, and all the more welcome when the cook can serve them. Sometimes the men work thirty hours at a stretch if the cod are running well, then turn in to snatch a few hours

of deep slumber, then out again for another long spell with the lines. The ship wallows in the troughs, and rears up on the crests. Cold water piles green on board, swirls frothing along the deck among the catch and cascades over the men, who crouch by the bulwarks with their lines. The ship groans and strains and works, and struggles always to free herself from the hampering weight of water, to heave her low bowsprit up clear of the seas, and shake herself along her whole length while the water foams in torrents through the scuppers. Generally at dusk she retires from the Banks, to lie hove-

When the hold is full there is no need to make the long return trip to the Faeroes to refit. Supply ships bring fresh stores and salt, and carry away the cod so that the smack can remain on the Banks to the end of the season. She may be away from home for three months, or nearly six. It is a source of bitter resentment that the embargo on the landing of crews from fishing vessels at Greenland ports applies to the Faeroemen equally with foreigners, although the Faeroes are a county of Denmark and should have every Danish privilege.

A catch of cod may total as much as 30,000 in a three-

Although the soil of the Faeroes is good, the almost constant rains make most of the land sheer marsh, and drainage is a back-

While the smacks are sailing for the Banks, the inshore fishermen are already at work, line-

At the washing stations there are large tubs on pedestals, with running water, and women working under contract split, clean and wash the fish, which is then stacked for several days with pure salt crystals between the layers. Afterwards it is spread skin down on flat rocks and beaches, or

on artificial paved platforms. Drying houses have recently been built, with artificial draughts, but it has been found that sunshine is necessary as well, so that all the fish is laid in the open for at least a part of the time it takes to dry.

Link with Spain

The women and girls who carry the fish to the drying beds keep a constant watch upon the weather, eyes cast frequently to windward. At the first sign of a coming shower — and there is scarcely a day in the Faeroes year without rain — all hands rush to gather in the fish, not only the workers who are paid to do so, but also everyone in the neighbourhood. All manner of tasks are abandoned while people rush to lend a hand.

Finally, when the fish are thoroughly dry, they are piled in big stacks and covered with tarpaulins, or else stored in sheds, built for the purpose, heaped to the corrugated iron roofs. Concrete and corrugated iron have largely superseded tarred Norwegian timber, stone and thatches of living grass in Faeroes building; but the effect is not unsightly, for most of the time the Faeroes landscape is softened by a thin drizzle or haze or Scotch mist, which tones down bright colours and makes the white concrete and gleaming grey iron tone with the greys and greens of their surroundings. The dried cod is exported in huge quantities to Great Britain, Spain and elsewhere. By far the largest proportion goes to Spain, on a reciprocal agreement, for Spain supplies the essential salt. In the Balearic Islands and on the Spanish mainland every little village shop has its heap of bacallao (codfish) in a corner, generally with the cat curled up happily asleep on top. Dried cod is popular also in Africa, where it is sometimes even used as currency among the West African colonies of the European Powers.

In Iviza, one of the smaller Balearic Islands, I walked one day to the salinas — great artificial lakes of seawater evaporating in the brilliant February sunshine — and there saw a ship from the Faeroes loading salt for the fisheries. The road wound along over a great expanse of glistening flats, cut up into a geometrical pattern by narrow dividing banks, with little sluice-

A few months before I had watched the laden smacks and supply ships-

THE SQUARE COUNTER of the Vestmanna, an auxiliary fishing vessel, can be seen on the right of this photograph, taken in Thorshavn Harbour. These ketch-

You can read more on “Grimsby -