© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

The Restless North Sea

A remarkable feature of the North Sea is its shallowness, due to the submergence of dry land in prehistoric times. Some of Europe’s most important rivers flow into the North Sea, and for centuries its dangerous shoals and currents have been a challenge to seamanship

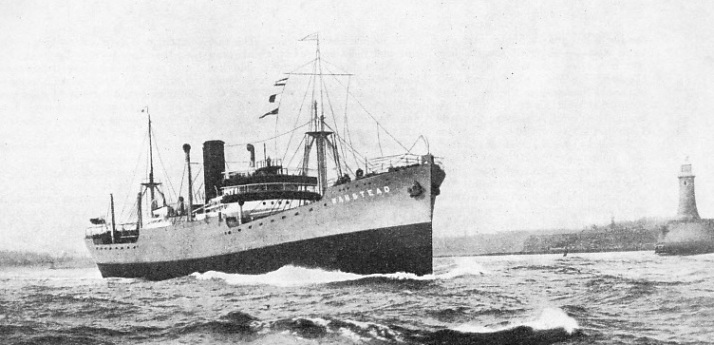

THE ENTRANCE TO THE RIVER TYNE is marked by a powerful light in a tower 85 feet high. The light is visible for a distance of 15 miles. The vessel in the photograph is the Wanstead, 5,423 tons gross, belonging to the British Steamship Co., Ltd. She was built at Dundee in 1928, and is registered at London. Her length is 405 ft. 10 in. between perpendiculars, her beam 54 ft. 3 in. and her depth 27 ft. 11 in.

THE greatest width of the North Sea is 360 miles, from the east coast of Scotland to the Skagerrak (or “Sleeve”), the gateway to the Baltic Sea. From the Strait of Dover to the artificial line dividing the North Sea from the Atlantic, off the Shetland Islands, the North Sea is 600 miles long.

From north to south the depth of the North Sea decreases. Near the Shetlands the 100-

Along the Danish coast a “shelf” extends from five to twenty miles out from the coast to the ten-

It is thought that when the world was young, much of the area now covered by the North Sea was dry land. The Thames and the great Continental rivers, the Rhine, Maas, Schelde (Scheldt), Elbe and Weser, flowed into a common estuary south of the Wash. The Strait of Dover did not exist, the English Channel being shut off by a belt of chalk joining England and France. What is now the Dogger Bank was an extensive forest, for many fossilized remains of trees are continually brought up from the bottom in that area, as well as the bones of many species of animals now usually associated with tropical climates.

The forests of the Dogger became submerged and the North Sea, much as we know it to-

Most of these banks consist of long, narrow, steep-

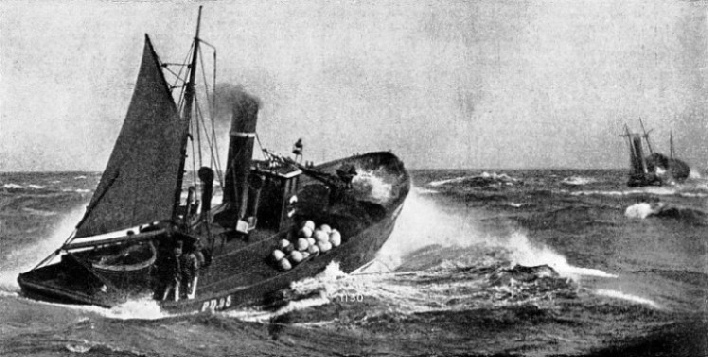

WIND AND SUNSHINE help to give this North Sea fishing trawler a pleasant run home. Because it is so shallow the North Sea is rarely calm even in good weather. The Dogger Bank, where a large part of the North Sea trawling takes place, has a depth varying from 10 to 20 fathoms (60 to 120 feet). Over the “South-

Fair Isle, a lonely rock, stands by itself in the channel between the Shetlands and the Orkneys. The coasts of the Orkneys, some ninety in number, alternate from low sandhills to steep, red cliffs 1,000 feet high. Heavy gales occur in this region, and the breaking seas send up clouds of foam hundreds of feet into the air.

Scapa Flow, the famous base of the Grand Fleet during the war of 1914-

The Orkneys are separated from the mainland of Scotland by the Pentland Firth, where the velocity of the tidal stream is greater than anywhere else in Great Britain. It runs at 10 knots, and in bad weather is impassable for small or low-

Duncansby Head is the north-

Pits in the Sea-

Farther south are three deep firths, the little-

The Grampian Range of mountains ends in Girdle Ness, the southern “bastion” of Aberdeen Harbour. A line of cliffs past Stonehaven to Montrose gives way to the sandhills of Arbroath and the mouth of the River Tay at Dundee.

A prominent object ten miles out at sea off the mouth of the Tay is the Bell Rock Lighthouse, a slender white pillar rising from the sea, built upon a treacherous reef. Some eighty miles off the coast is a series of “Devil’s Holes”, pot-

Shipbreaking is carried on extensively in the Firth of Forth and many units of the German Fleet raised from Scapa Flow, as well as famous liners, have been towed to their last berth here. The Bass Rock stands guard over the southern side of the entrance to the firth.

OUTWARD BOUND IN HEAVY WEATHER, Peterhead drifters leaving Yarmouth for the North Sea fishing grounds. Yarmouth Roads provide adequate shelter for shipping, but the Scroby Bank and other shoals which lie outside are constantly shifting. Sudden storms are occasionally encountered here. Daniel Defoe, author of Robinson Crusoe, relates that in 1692 a fleet of 200 colliers left the Roads in calm weather, and that 140 of them foundered in a sudden north-

Past the English border at Berwick-

Coal used to be loaded into boats called “keels”, carrying about 20 tons, propelled by large oars or “puys”. Hence was derived that famous old song Weel may the keel row. Nowadays massive “staithes” tip truckloads of coal directly into ships’ holds.

On October 31, 1914, the hospital ship Rohilla drove on to the rocks just outside Whitby, Yorks, during a gale, and rapidly broke up. There was unfortunately great loss of life, although she was near the shore. The cliffs that line this part of the shore attain their greatest height at Hayburn Wyke (600 feet) and then decline towards Scarborough. At Filey a curious formation of rock, known as Filey Brig, juts out for half a mile into the sea; the rock is dry at low tides. South of Filey chalk cliffs are encountered, jutting out into Flamborough Head (450 feet), with its lighthouse and signal station. The cliffs are the nesting places of innumerable sea birds.

About sixty sea miles east of Flamborough is the western edge of the Dogger Bank. This is a large submerged island, some 130 miles in length from south-

The coast from Flamborough to the mouth of the River Humber, at Spurn Head, is exposed to the full force of north-

The Humber gives access to the important fishing port of Grimsby, the railway dock at Immingham and the port of Kingston-

About eighty miles out a series of long, narrow ridges is found, called respectively the Indefatigable, Swarte, Broken, Well, Ower, Haddock, Leman, Outer Dowsing and Cromer Knoll, and with them two “depressions” known as the Sole Pit and the Coal Pit. Inshore of the Outer Dowsing a cluster of shoals exists shorewards, called the East Dudgeon and Docking Shoals, the Triton Knoll, the Inner Dowsing, the Burnham Flats and the Sheringham Bank. The Wash is an inlet extending inland for twenty miles and covering an area of about 250 miles, of which 130 dry out at low water. The ports of Boston and King’s Lynn are approached by long, narrow channels through the sandbanks.

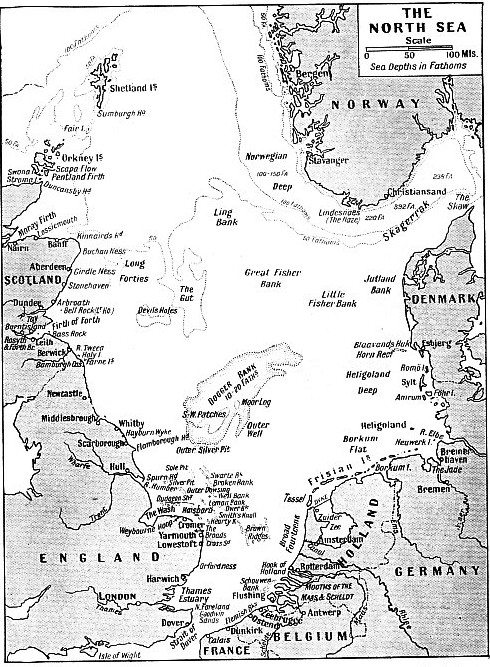

FROM THE SHETLANDS to the Strait of Dover extends the ocean known as the North Sea. At its greatest width, from the east coast of Scotland to the Skagerrak, it is 360 miles wide; its length is about 600 miles. In most parts the North Sea decreases in depth from north to south. Between Scotland and Norway the average depth is 50 80 fathoms, or 300 480 feet ; south of the River Humber the depth is as little as 10 fathoms. These shallows, however, are broken by deeper channels. Off the Norwegian coast there is a depth of 480 fathoms (2,880 feet).

At Weybourne Hoop is a shingle beach that has always been associated with threatened invasions of England. A writer of 1798 says: “At a place called Waborne Hope . . . the shore is stony, and the sea so deep that ships may ride and lay against it.”

Another system of sandbanks lies off the coast between Cromer and Yarmouth, Norfolk. These are parallel ridges, known as Smith’s Knoll, Hearty Knoll, Winterton Ridge, Hammond’s Knoll, and the dangerous Haisborough Sand.

The last-

Behind the line of sandhills, clothed with “marram” grass, lie the Broads, protected only by these sandhills against an inrush of the sea over the low-

Abreast of Yarmouth are the famous “Roads”, formed by a channel protected by the Cockle, Caistor, Scroby, Corton and Holm Sands and, farther out, the Cross Sand. The Scroby Sand has had some remarkable changes. It was formed in the sixteenth century, grass grew upon it, and picnics were held there. In 1582 it was swept away by a strong tide aided by an east wind. In 1922 it rose again from the sea and became dry at low water. As recently as 1934 the buoys which guard it had to be extensively altered to meet its changes. Daniel Defoe tells us that

in 1692 a fleet of 200 colliers had taken refuge in Yarmouth Roads. The weather having turned fair, they left to continue their voyages when a sudden storm sprang up from the north-

Complicated Sandbanks

Yarmouth, and its near neighbour, Lowestoft, are to-

All along this coast the sea is eating away the land and many houses and even whole villages have fallen over the crumbling cliffs into the sea. At Dunwich, to-

About fifty miles off the coast here the North German Lloyd liner Elbe was sunk in collision with the coaster Crathie in 1895. Only fifteen passengers and five of the crew were saved. More banks lie off the coast here, among them the Sizewell and Aldborough (Aldeburgh) Napes, and then the remarkable shingle bank on the mainland, culminating in Orfordness. Southward of this, the estuary of the Thames is approached, with its complicated mass of sandbanks. This estuary is described in the chapter “London’s Link with the Sea”.

The North Sea meets the English Channel in the Strait of Dover. A complicated system of shoals known as the “Flemish Banks” lies for thirty miles out from the French and Belgian shores. The most important banks are the Sandettie, Ruvtingen, Ratel, Fairy, North, West and East Hinder, Bligh, Thornton, Ostend, Stroom and Wenduyne Banks.

The approach to the important port of Dunkirk is by way of the West Pass, a channel close to the shore and guarded seaward by the Dyck Sand. From these a channel exists, through the Zuydcoote Pass, near the shore, inside a line of sandbanks along to Ostend. The Belgian coast consists of low sandhills to the Dutch frontier just south of the estuary of the Schelde, which leads up to the great port of Antwerp. At the mouth of the Schelde, on the northern side, is the town of Flushing.

IN LOWESTOFT HARBOUR the pleasure steamer Lord Nelson passes through the fishing fleet on its way out to sea. The Lord Nelson was a paddle steamer built in 1896 at Preston, Lancashire. She formerly plied between Yarmouth and Lowestoft, the two great centres of the North Sea fishing industry. Large fleets of drifters and trawlers use these ports.

A large delta, composed of an involved system of low islands, and formed by the junction of the Rivers Maas and Schelde, lies behind the Schouwen Bank. Then follows, past the Hook of Holland and the “New Waterway” leading to Rotterdam, a clear stretch of sea unencumbered by sandbanks, flinging all its might upon the low Dutch coast protected by massive dykes and sandhills. Much of Holland is below sea-

A barrier of islands and banks stretches across the mouth of the Zuider Zee, itself fast returning to dry land, thanks to the Dutchmen and their reclamation schemes. Tessel, Vlieland and Terschelling are the names of these islands, the one separated from the other by a “Gat” — as, for instance, Schulpen Gat, Engelsmans Gat, Terschelling Zeegat.

A few more islands occur towards the German frontier — Ameland, Schiermonnikoog and Rottum. Then comes the estuary of the Ems, divided by the island of Borkum into the Eastern and Western Ems. Out to sea runs the comparatively shallow “Borkum Flat”, with a depth of from ten to sixteen fathoms. Then comes the archipelago known as the Frisian Islands, well known to readers of The Riddle of the Sands, by Erskine Childers.

These low-

ground of numbers of Germans. The islands are so low that out at sea, on a summer’s morning, the buildings and hotels can be seen apparently rising from the water, for the land they stand on is invisible.

The bay of the Jade and the mouths of the Rivers Weser (with the ports of Bremerhaven and Bremen) and Elbe run into one another through great banks of sand, mostly dry at low water, and intersected by numerous channels, called “Gats”, “Lochs”, “Tiefe”, “Balge”. The transition from sea to river is almost unnoticed when sailing into the Elbe.

The World’s Oldest Lighthouse?

The island of Neuwerk, itself little better than a sandbank, but above the high-

The Danish coast now runs northward to the Skaw, a long, low, featureless shore. To enable mariners to ascertain their whereabouts, huge wooden beacons, or “shapes”, squares, crosses,

diamonds, triangles and the like, forty to fifty feet high, are erected along the coast. Each differs from the others, so that they may be easily recognized from the sea.

Off the coast lie the Jutland Bank and the Little Fisher Bank, the scene of the world’s biggest naval action, known in Great Britain as the battle of Jutland and in Germany as the battle of Skagerrak.

The Skaw, the northern “tip” of Denmark, ends in a narrow spit extending two miles from the shore, on which the sea breaks heavily. The north side of it is steep, with one and a half fathoms close to it.

Across the Skagerrak on the Norwegian coast is the intricate maze of rocky islands known as the Skargard, with high cliffs on the mainland intersected by long, deep fjords running for miles back into the land. A feature of some of the fjords is their tremendous depth, which in places amounts to nearly 700 fathoms (4,200 feet).

The tidal wave enters the North Sea at either end. The rise of the tide varies from half a foot to 22 feet in various parts. Its rise is 14 feet higher on the coast of England than on the opposite shores of Denmark.

The height of the tide is much affected by the wind. A strong wind “piles up” the water and may lead to an exceptionally high or low tide.

Conversely, a strong westerly wind and a neap tide combine to take the water out of the Thames.

EAST GOODWIN LIGHTSHIP is situated about one and a half miles east of the Goodwin Sands, off the North Foreland, Kent. The lightship is a red vessel and has a light tower amidships. She shows a white flash of less than a second duration every 15 seconds, and this light is visible for II miles. She is equipped with a diaphone for use in fog and with a submarine oscillator which sounds the letters E.G. in Morse code every 30 seconds. She has also a wireless fog signal, which transmits M.E.G. in Morse on a wavelength of 1,008 metres. In foggy weather transmissions are made ten times in every hour.

You can read more on “Britain’s Changing Coast Line”, “London’s Link with the Sea” and “Signposts of the Sea” on this website.