© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Surrender of the German Fleet

On November 21, 1918, the mighty German High Seas Fleet was handed over to the British Fleet for internment at Scapa Flow, in the Orkney Islands. Before peace negotiations had been concluded, however, the German sailors scuttled their ships

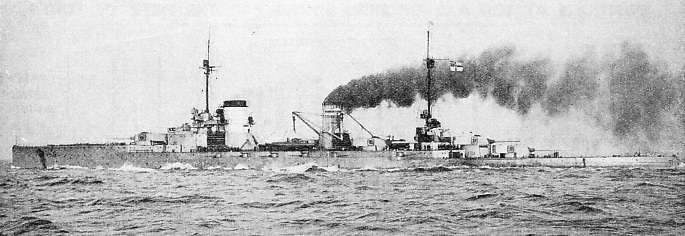

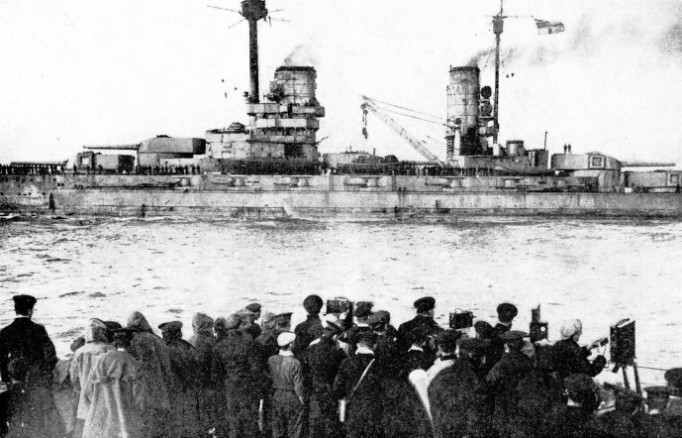

THE IMPERIAL WHITE ENSIGN of the German battle cruiser Seydlitz was still flying as she steamed across the North Sea under the orders of Admiral Sir David Beatty, who was in charge of the arrangements for taking over the German Fleet. Built in 1912, of 25,000 tons displacement, the Seydlitz was 656 feet long, with a beam of 93 ft. 4 in.

AT 5 a.m. on November 11, 1918, the Armistice terms were signed in the saloon of a special train that had been drawn up in a siding in the Forest of Compiegne in Northern France. Marshal Foch and Admiral Sir Rosslyn Wemyss were the principal signatories on behalf of the Allies, and the German Secretary of State, Herr Erzberger, on behalf of the new Government of Germany.

Two clauses of the Armistice Agreement contained the following provisions: that Germany was to surrender to the Allies and the U.S.A. 160 submarines, complete with armament and equipment, in specified ports, and that German surface warships designated by the Allies and the U.S.A. were to be disarmed, interned in neutral or Allied ports and placed under the surveillance of the Allies and the U.S.A., with only caretakers left on board. The ships designated were six battle cruisers, ten battleships, eight light cruisers (including two minelayers), and fifty destroyers of the most modern type. All other surface warships were to be completely disarmed and placed under the supervision of the Allies and the U.S.A.

Thus Germany was to be deprived of all naval power. The terms were severe, but the original Admiralty proposals were even more severe. They proposed the complete surrender of the Fleet; but the Allied Premiers decided that only the submarines were to be surrendered and that internment of the remaining German naval forces to be handed over was the most that could be demanded.

The Allied Naval Council left the enforcement of the terms of the Armistice in the hands of Admiral Sir David Beatty, Commander-

On October 21, 1918, the German Chancellor decided that all attacks on passenger vessels by U-

Th e German Fleet had been through a wearying war. The lack of unity between officers and men, as well as the inferior quality of the food, had affected the spirit of the restless crews. Discontent, which had first appeared in 1917, had been slowly spreading. When the prospects of an armistice and peace were followed by orders to go to sea and engage the British Fleet, this discontent was again brought to a head. On October 25 a number of German submarines put to sea to take up positions south of the Firth of Forth in readiness for the naval attack on the British Fleet. On October 27 and 28 the German Fleet began to assemble in Schillig Road, the outer anchorage off the River Elbe, ready for the sortie. News leaked out that a “death or glory attack” was to be made, and this was used as propaganda among the men of the Fleet, who carried out their orders for preparation, but murmured to each other: “Why go out and die when peace is at hand?”

e German Fleet had been through a wearying war. The lack of unity between officers and men, as well as the inferior quality of the food, had affected the spirit of the restless crews. Discontent, which had first appeared in 1917, had been slowly spreading. When the prospects of an armistice and peace were followed by orders to go to sea and engage the British Fleet, this discontent was again brought to a head. On October 25 a number of German submarines put to sea to take up positions south of the Firth of Forth in readiness for the naval attack on the British Fleet. On October 27 and 28 the German Fleet began to assemble in Schillig Road, the outer anchorage off the River Elbe, ready for the sortie. News leaked out that a “death or glory attack” was to be made, and this was used as propaganda among the men of the Fleet, who carried out their orders for preparation, but murmured to each other: “Why go out and die when peace is at hand?”

Admiral von Hipper issued orders on October 29 to raise steam so that the fleet could sail that night; but when the time for sailing arrived the stokers in two of the battleships drew fires and refused to sail. Admiral von Hipper decided to wait until the next day, but the odds were against him. Bad weather added to his difficulties. He ordered the Fleet to disperse to their harbours. The mutiny spread from ship to shore, and from shore to ship. By November 7 the Red Flag was flying from all ships, except submarines, in the German harbours. Kiel and Wilhelmshaven were under the rule of the President of the Soviet of Workers, Soldiers and Sailors, an ex-

Some steps had already been taken towards dismantling the ships, for the rioters had made free with everything they could lay hands on from the vessels. At Wilhelmshaven there was a scene of chaos. People were singing the Internationale, and the Soviet police could not prevent them from trafficking with naval stores. Anything and everything was purloined -

Then came a message that rather baffled the Soviet Council of the North Sea Station: “The Commander-

Meeting the German Delegate

A statement was issued by the President of the Wilhelmshaven Soviet: “The Plenipotentiaries have been given full powers to take part in the discussion regarding the execution of the Armistice conditions, and to conclude treaties. The authorization has been signed by the President of Oldenburg and Ostfriesland, Bernard Kuhnt. It also bears the signature of Admiral von Hipper, who takes part in the minor capacity of technical adviser, the Executive Organ being the Workers’ and Sailors’ Soviet.” Admiral von Hipper at once sent for Rear-

As soon as the Konigsberg sailed on her unique errand, Admiral von Meurer insisted that the old Imperial Naval Ensign should be hoisted, ignoring the fact that the Sailors’ Soviet was on board in command of the ship. In addition to the Naval Ensign, Admiral von Meurer’s flag as Rear-

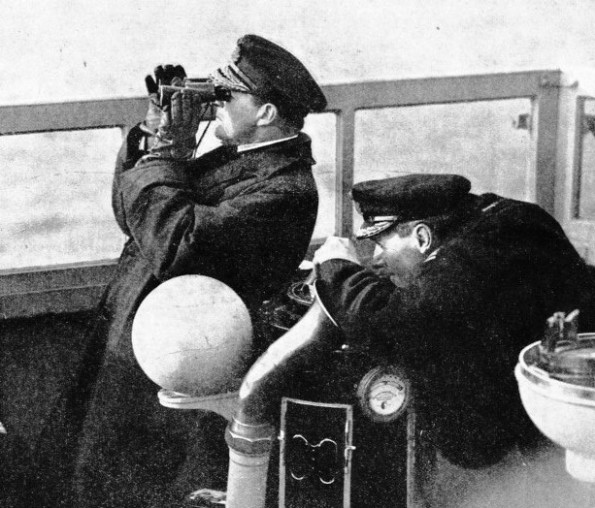

ADMIRAL SIR DAVID BEATTY, Commander-

In the meantime Rear-

History records many instances of the surrender of ships during an action, with the Commanding Officer handing up his sword. This was the first instance of a fleet being handed over, submarines in surrender and surface craft for internment. Admiral Beatty reminded his officers and men that a state of war existed during the Armistice, and that no international compliments would be paid. Relations with the German officers and men were to be strictly formal, and no conversation was to take place except on duty.

Soon after 7 p.m. Admiral von Meurer stepped on board the Flagship. He was received correctly. The quartermaster piped the side and the officer of the watch saluted. Admiral von Meurer clicked his heels, saluted, and was then conducted by the Captain of the Fleet, Commodore H. Brand, with the Captain of the Queen Elizabeth and other officers, to Admiral Beatty’s cabin. Royal Marines with fixed bayonets lined the deck.

An Historic Conference

Even the most hard-

Admiral Beatty sat at one side of a long table in the cabin. Opposite him sat Admiral von Meurer, with three officers and his personal aide-

Many details had to be discussed. Admiral Beatty prescribed exactly which ships were to be sent over, how much coal and stores they were to carry, and what course they were to steer. Procedure was necessarily slow, for everything had to be repeated by the interpreter. Frequently Admiral von Meurer had to communicate by wireless with Germany to obtain the information required. It was not until late the following night that final arrangements were made. Admiral von Meurer left the Queen Elizabeth in the unostentatious manner in which he had embarked. He was taken back to the Konigsberg, and sailed at once for Germany.

On either side of the North Sea preparations were being made for the last act of this great drama. Admiral Tyrwhitt was to receive the surrender of the U-

AFTER THE SURRENDER British officers were sent aboard the German U-

On the German side the arrangements were not so simple. Many difficulties arose. The Workers’ Council at first called on the Government to resist the “uncalled-

The surface ships were depleted of ammunition, instruments and stores as rapidly as possible, but it was no easy task after the upheaval that had taken place a few days before. False rumours and propaganda were in circulation, intimating that all the other Navies were flying the Red flag. The submarine crews were told that they would be shot or imprisoned when they reached England. All these things naturally stimulated the people to unrest and disorder. Bonuses, insurances and other considerations overcame some of the submarine crews’ difficulties, and by November 18 the first batch of twenty U-

Of the 150 U-

At 7 a.m. on November 20, Admiral Tyrwhitt in the light cruiser Curacao, with four other cruisers and a number of destroyers, was waiting at the rendezvous about thirty-

These were followed soon after by the twenty U-

The U-

As soon as the outer buoys of the harbour were reached, British officers and men boarded the vessels to take them over. Orders had been issued by Admiral Tyrwhitt, and the “taking over” was done in an orderly and rigid manner. The British officers saluted on stepping aboard, and asked for papers. Each German officer then handed over a written statement concerning his vessel. The German crew was moved forward while the British officers went to the conning-

Day after day the same procedure was followed, varied at times on account of bad weather, which caused delay in mooring and in the transferring of crews. Many famous U-

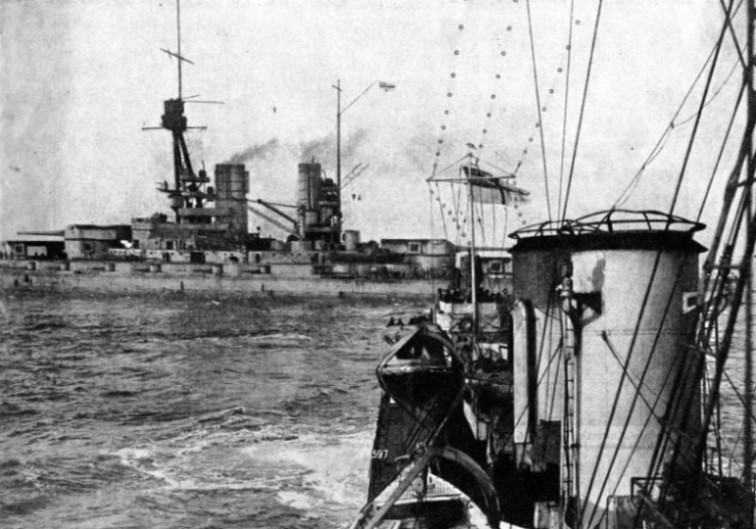

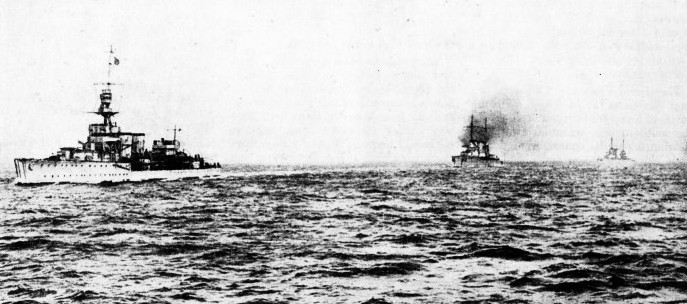

THE MOST POWERFUL BATTLESHIP in the German Navy, the Bayern, is shown steaming between the two lines of the Allied Fleet on her way to the Firth of Forth. The Bayern was completed on October 30, 1915, and had a displacement of 28,000 tons. Her overall length was 626 ft. 8 in., and her beam 99 ft. 9 in. Her Imperial White Ensign was not lowered until sunset on November 21, 1918.

On November 17 Admiral von Hipper had to decide who was to accompany the Sailors’ Soviet and help them take the fleet to Rosyth. It was doubtful whether Admiral von Meurer would be back in time, for he had reported foggy weather. Admiral Ludwig von Reuter was asked to take over the difficult and unwanted “command”, a position officially described as “technical adviser” to the Soviet. Seldom, if ever, has a man been offered such a thankless and heart-

The battleship Friedrich der Grosse acted as his Flagship. He proceeded on board and hoisted his Vice-

The Sailors’ Soviet intended that these ships should fly the Red flag, but it was pointed out that if they did so they were liable to be treated as pirates and sunk. At the last moment, therefore, the Red flag was hauled down and all ships flew the Imperial Naval Ensign. The Admiral and Commodore flew their personal flags as well. Some of the ships met with difficulties in their engine-

The speed of the fleet was restricted to eleven knots. For various reasons no higher speed could be obtained. The difficulties of handling ships with a mixed command and a mixed crew can easily be imagined. There was also the danger of mine fields, although special vessels were employed to mark these.

Intricate Operation Orders

Slowly steaming in cruiser formation past the island of Heligoland, past Jutland, a scene reminiscent of May 31, 1916, the second Naval-

Later, in the silence of the night, there was a deafening explosion. It was reported that the destroyer V 20 had struck a mine. She sank with the loss of two men killed and three wounded. As soon as Admiral Beatty received this report, he ordered another ship to be prepared in place of the destroyer.

By midnight on November 20, Admiral von Reuter, with his ships at intervals of about four hundred yards, was about one hundred miles from May Island, at the mouth of the Firth of Forth. Two hours later, at 2 a.m. on November 21, the Grand Fleet began to stir. Operation orders Z.Z. gave every instruction in detail. Every vessel knew the exact time to move, the exact position to take up in the great armada and the exact courses to be steered.

Battleships, battle cruisers, cruisers, light cruisers, flotilla leaders, destroyers, aircraft-

A GERMAN BATTLESHIP of the Konig class passing through the lines of the Grand Fleet in the North Sea on her last voyage under the Imperial White Ensign. The ships of the Konig class had a displacement of 25,800 tons, and were built between April 1913 and February 1914.

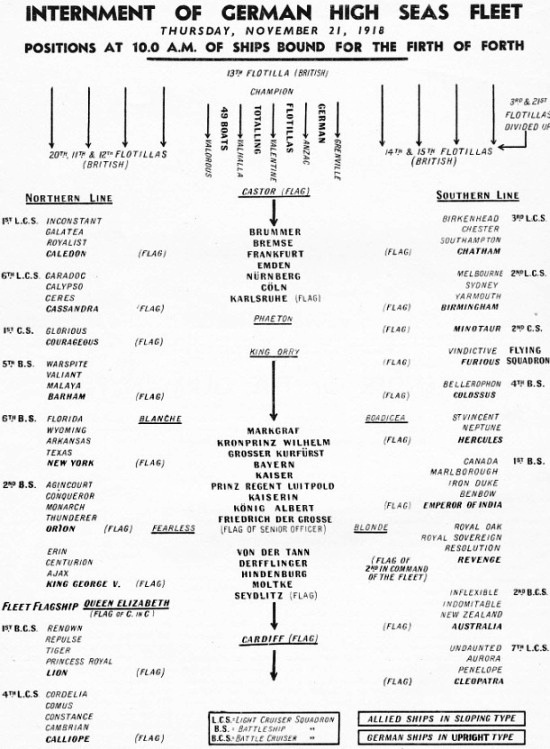

The Grand Fleet approached in two lines fifteen miles in length. In the northern line were thirty-

The morning was misty, but the sun penetrated the clouds and at about 8 a.m. visibility extended about four miles. The curtain of fog gradually lifted and all eyes were strained to catch a sight of the enemy. The destroyers were the first to report the German Fleet, which was led by the Cardiff between the two lines of the Grand Fleet. At an order from Admiral Beatty the lines turned sixteen points so that the German ships were sandwiched. The Soviet officials and supporters peered through the mist, but could not see any Red flags on the British ships. They had been deceived. The British Navy did not fly the Red flag.

German Flag Hauled Down

Thus the procession of more than two hundred vessels, including fifty-

The crews of the Grand Fleet had scrupulously carried out their orders not to cheer or show any sign of rejoicing at the arrival of the enemy, but there were no orders to prevent them from cheering their own Commander-

Soon after the ships had all been anchored, Admiral Beatty signalled to Admiral von Reuter that the German Flag was to be hauled down at sunset and not hoisted again without permission. The German Admiral protested and stated that the ships were only being interned, but it was pointed out that during a “state of war” it was impossible to have an enemy flag flying in British ports. At sunset (3.57 p.m.) that evening, in the mist and twilight, the German Flag was hauled down, to be hoisted only once more for a brief period. At 6 p.m. a service was held in all ships. Admiral Beatty had set the example in a signal issued earlier in the day. “It is my intention to hold a service this evening at 18.00 (6 o’clock) to-

THE SHELTERED WATERS of Scapa Flow, in the Orkney Islands, where the German High Seas Fleet was sunk by its own crews to prevent the vessels from falling into the hands of the Allied Powers if peace negotiations broke down. This photograph shows ships of the 4th Battle Squadron of the Grand Fleet exercising in Scapa Flow during the war of 1914-

Meanwhile, Commodore H. M. Hodges went on board the German flagship with an interpreter to convey orders concerning the inspection of the ships and the instructions to be followed while in British ports. He refused to deal with the Soviet emissaries and asked to be conducted to the Admiral. Among the orders issued to the German ships were instructions that no boats were to be lowered and no visits to be made between ships. There was no leave ashore, and a strict censorship of letters was instituted. All food required was to be obtained from Germany. After Commodore Hodges’ visit, officers and men from the fleet were sent aboard the German vessels to see that orders as to the removal of ammunition, breech-

Preparations had also been made for the permanent internment of the ships. The terms of the Armistice had provided for the use of an Allied port if necessary. It was decided that the ships should be sent to Scapa Flow, a small, bleak harbour in the Orkney Islands. To Scapa Flow, therefore, were sent the destroyers, followed by the larger ships as they became ready.

The allowance of personnel was 200 men for a battle cruiser, 150 for a battleship, sixty for a cruiser and twenty for a destroyer. The total German force consisted of 200 officers and 4,300 men. Admiral von Reuter went back to Germany on account of ill-

In January 1919 Admiral von Reuter was persuaded to return to Scapa by the new Government in Berlin. On his arrival he found that many of the German crews had become Bolshevist in the bleak monotony of Scapa routine. He transferred to the cruiser Emden, which was fitted up with flagship accommodation; but his life was dull and undignified, and such news as he obtained came to him several days late from the British newspapers.

It was from these newspapers that Admiral von Reuter learned how the peace negotiations were progressing. He came to the conclusion that if the negotiations failed, it was his duty to prevent the ships under his orders from falling into the hands of the enemy. He could not raise steam and sail away, or attack, and the only alternative was to destroy the Fleet. He wrote to Germany a letter, which was duly censored, asking for a transport for 2,500 of his men, as he no longer required them for the safety of the ships.

Guard Squadron Outwitted

Early in June 1919, transports were sent and Admiral von Reuter got rid of many men, including those on whom he could not depend. A secret letter was addressed to all commanders and a secret signal arranged:-

On June 21, a fine sunny day, Admiral von Reuter received his newspapers dated June 16. The news he read gave him the impression that the Armistice would come to an end without the agreement of any peace terms. He was debating the advisability of acting at once when one of his officers reported that Admiral Sydney Fremantle, in command of the guard squadron, was proceeding to sea with his battleships and destroyers. Admiral Fremantle had decided to take advantage of favourable weather and carry out long-

As soon as the main body of the British Fleet was out of the harbour, Admiral von Reuter hoisted the secret signal. It was quickly seen and obeyed. The German Imperial Flag was hoisted by all the German ships, and their crews went below to open the sea-

When Admiral Fremantle received the news he sent all his destroyers back at full speed and followed close after with his battleships; but it was too late. All the battleships sank, except the Baden, which was beached with the light cruisers Emden, Frankfurt, Nurnberg and eighteen destroyers.

Admiral von Reuter was made a prisoner of war on board the British flagship, but, in spite of the tremendous loss of ships, his action solved the difficult task of dividing them up amongst the Allies. On January 21, 1920, Admiral von Reuter and 1,800 officers and men were released from internment and sent back to Germany. Thus ended a series of the most remarkable incidents ever recorded in naval history.

LEADING THE GERMAN FLEET to internment, H.M.S. Cardiff was followed by the German battle cruisers Seydlitz, Moltke and Hindenburg. As they passed between the lines of the Grand Fleet, they brought to a conclusion an important chapter of naval history.

You can read more on “The Battle of the Falklands”, “German Shipping” and

“Raising the German Fleet” on this website.