© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Navies of the Dominions

The Navies belonging to the British Commonwealth of Nations are administered in peace time by the separate Dominions. If they were put at the disposal of Great Britain in the event of war, they would become an integral part of the Royal Navy

THE NAVY GOES TO WORK - 10

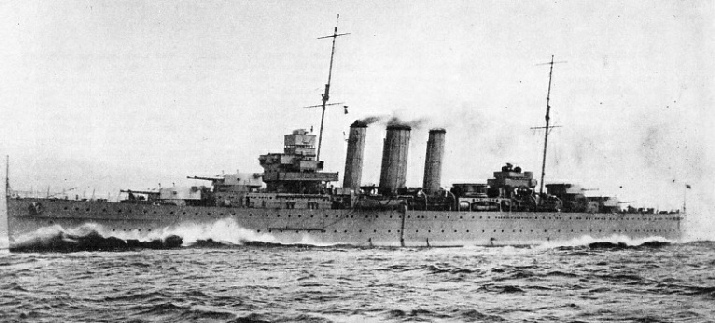

AN AUSTRALIAN CRUISER of 9,850 tons displacement, the Canberra was built by John Brown & Co., Ltd., Clydebank, and completed in 1928, with her sister ship Australia, illustrated below. Geared turbines of 80,000 horse-

THE naval forces of a Commonwealth whose territories straddle the globe must needs be widely dispersed. So it happens that on any given day units of the British Navy will be found in the North and South Atlantic, the Pacific, the Indian Ocean, and almost every navigable part of the world, including the great rivers of China.

While the main burden of policing the 85,000 miles of ocean routes which form the arteries of the Commonwealth necessarily falls on the Royal Navy, the Dominions are not unmindful of their obligations in this respect and, with one exception, they all maintain naval forces at their own charge.

Thus we find catalogued in the Navy List the Royal Australian Navy, the Royal Canadian Navy, the Royal Indian Navy, the New Zealand Division and the South African Naval Service, besides Naval Volunteer Forces in Kenya, Hong Kong and Singapore. Although the Dominion fleets are administered in peace time by their respective Governments, they have precisely the same organization as that of the Royal Navy, and would, if precedent be followed, automatically pass under the control of the British Admiralty in time of war.

The sum total of the fighting strength of the Dominion Navies is not formidable at the present time. Under the impulse of post-

They are a constant reminder that the sea is all one and that the fortunes of the whole Commonwealth, from Great Britain herself to the smallest coral-

Moreover, small though they be at the present date, the Dominion naval forces are so organized as to be capable of expansion should the need arise. A striking example of this capacity was furnished during the war of 1914-

The principle that the Dominions, or Colonies as they were formerly termed, should be to some extent self-

So it came about that the various States of what was to become eventually the Commonwealth of Australia began to provide for their own defence in the form of small ironclads, gunboats and torpedo craft. Whether these tiny local squadrons would have deterred a would-

Australia’s naval history really begins in 1887, when, as the outcome of a Colonial Conference held in London, the British Government agreed not only to continue the upkeep of the Royal Navy squadron regularly stationed in Australia, but also to build a special auxiliary squadron of five cruisers and some gunboats to operate exclusively in Australasian waters. Part of the cost of these ships was defrayed by Australia and New Zealand. The special squadron remained in existence till 1902, when it was replaced by a force of more modern ships. By this time, however, Australian federation had been accomplished and the newly born Commonwealth cherished a natural ambition to possess a navy entirely its own.

For some years, however, matters were held in abeyance by political and economic difficulties, and not until the naval crisis of 1909, when revelations of Germany’s vast naval programme sent an electric shock through the British Empire, did the Australian Government commit itself to the creation of the long-

In the five years preceding the war of 1914-

Although the war clouds broke, almost before the Royal Australian Navy had emerged from the chrysalis stage, the new service acquitted itself most gallantly and earned laurels in more. than one theatre of hostilities. Everyone knows how the cruiser Sydney caught and destroyed the Emden, that most dangerous of all German raiders, and how splendidly the young Australian sailors, many of them mere boys, behaved under fire.

Although the war clouds broke, almost before the Royal Australian Navy had emerged from the chrysalis stage, the new service acquitted itself most gallantly and earned laurels in more. than one theatre of hostilities. Everyone knows how the cruiser Sydney caught and destroyed the Emden, that most dangerous of all German raiders, and how splendidly the young Australian sailors, many of them mere boys, behaved under fire.

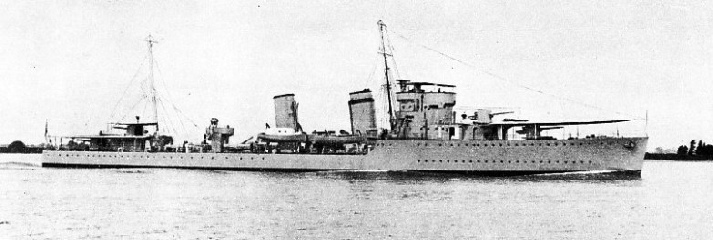

WITH A DISPLACEMENT OF 9,870 TONS, the Australia is slightly heavier than her sister ship, the Canberra, illustrated above. Her other dimensions are identical with those of the five British cruisers of the Kent class. They have an overall length of 630 feet, a beam of 68 ft. 4 in. and a mean draught of 16 ft. 3 in.

Yet the Sydney-

The light cruisers Sydney and Melbourne served also for two years in the North Sea, and towards the end of the war were joined by their sister ship Brisbane. An Australian submarine was lost in the Dardanelles and Australian destroyers were actively engaged in the anti-

During the first years of peace after 1918 the Australian Commonwealth, suffering from the economic strain of its magnificent war effort, found it expedient to make drastic reductions in the armed forces, by which the Navy was the chief sufferer. Ships and men were paid off until, in 1924, the R.A.N. had become a mere shadow of its former self. Then, however, the process of disintegration was suddenly arrested by the news that the Home Government had decided to abandon work on the new base at Singapore.

As the people of Australia, whether rightly or wrongly, considered the completion of this base to be absolutely essential for their future security, there were indignant protests throughout the Commonwealth. When these proved unavailing the Federal Government took stock of the whole position and eventually decided to divert to the building of new warships the money which had been set aside as Australia’s contribution to the cost of the Singapore scheme.

Two cruisers of the 10,000-

One of the latest additions to the Australian fleet is the 7,000-

In addition to the foregoing vessels the fleet includes five more destroyers presented by the Home Government in 1919, two sloops laid down at Sydney in 1936, and a number of auxiliary vessels. Owing mainly to shortage of personnel, the only ships in full commission during 1936 were the Australia, Canberra, Sydney, three destroyers and the depot ship Penguin.

Through Jutland Unscathed

From time to time units of the Australian squadron join up with the New Zealand Division and the British China Squadron for combined exercises. In recent years it has been customary for one Australian cruiser to serve for a period with the Mediterranean Fleet, her place in Australia being taken by a Royal Navy cruiser.

The future development of Australian naval power will depend in the first instance on the state of the Commonwealth finances but, judging from past history, any change in world politics which seriously threatened British interests would be followed by an expansion of the Australian forces. The R.A.N. is administered by a Naval Board under the Minister of Defence, assisted by a First Naval Member corresponding to the First Sea Lord of the British Admiralty.

Officers are trained at the Naval College at Jervis Bay (Federal territory), and other establishments include the dockyard at Sydney, naval armament depots and victualling yards. In an emergency the Australian fleet would join up with the other British naval forces in the Pacific, and their united strength would then be brought to bear where it was most needed.

New Zealand claims to be the first Overseas Government to have acquired a local naval force, for as long ago as 1863 she bought and armed four cargo steamers and employed them in the second Maori War. Subsequently the Dominion, in common with Australia, made an annual contribution to the upkeep of a Royal Naval squadron in Australasian waters, but when the naval crisis of 1909 arose New Zealand gave proof of her fervid loyalty to the Empire by offering to bear the entire cost of building a battle cruiser.

This generous offer was accepted, and H.M.S. New Zealand was duly built. Originally she was intended to serve in Far Eastern waters but, as the situation in the North Sea became more critical, the Dominion Government consented to the transfer of its ship to the British Home Fleet, thereby furnishing yet another example of self-

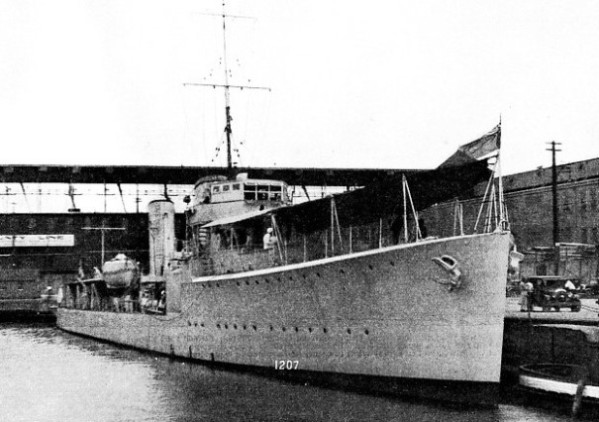

THE HULL OF THE CANADIAN DESTROYER SAGUENAY was specially strengthened to withstand ice pressure encountered in wintry North American waters. Otherwise, the Saguenay, completed with the Skeena in 1931, is built on the lines of the Acasta type destroyers of the Royal Navy. A vessel of 1,337 tons displacement, the Saguenay has a designed speed of 35 knots and is driven by geared turbines of 32,003 horse-

So the outbreak of war in 1914 found the New Zealand a unit of Admiral Beatty’s famous “Cat Squadron”, in which capacity she helped to make history in all the great battles fought in the North Sea. In the Jutland action (May 31, 1916) the ship, although repeatedly under extremely heavy fire, escaped without a serious hit and was the only one of Beatty’s ships to suffer no casualties. When the action began, Captain John F. E. Green, commanding the ship, put on an apron which had been presented to him by a Maori chieftain with the assurance that the wearer would walk unscathed in battle. Whether the presence of this “magic” garment had anything to do with the New Zealand’s amazing immunity during the action at Jutland must be left for the reader to decide.

Since the war of 1914-

As the Dominion does not own any large naval dockyard or establishment of its own, the ships of the squadron have to return to Great Britain when in need of refit. If trouble threatened in the Pacific the New Zealand Division would promptly attach itself to the Australian and other Imperial naval forces in that ocean.

On the other side of the Pacific lies the western seaboard of Canada, whose naval policy has undergone many fluctuations in the past and is at the present time still nebulous and uncertain. Though the people of Canada yield to none in Imperial loyalty, of which, indeed, they gave abundant proof in 1914-

With a 3,000-

Canadian naval history opens in 1880, when the British Government presented a corvette for training purposes. The ship, however, was in such a bad state of repair that the Canadian Government had to spend a large sum of money on making her seaworthy. This incident did little to promote naval enthusiasm among the taxpayers of the Dominion. Little further progress was made until 1905, when Canada offered to take over and maintain the dockyards of Halifax, Nova Scotia and of Esquimalt, on the Pacific coast. The offer was accepted by the Imperial Government.

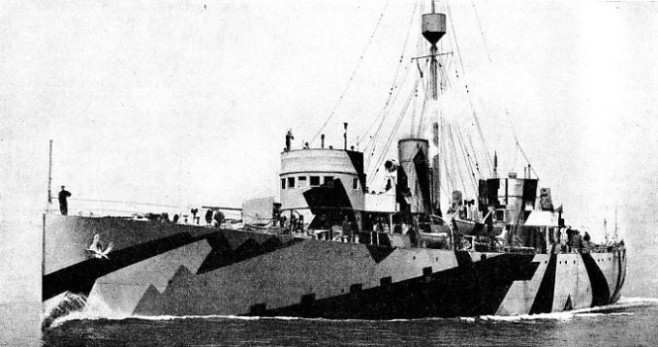

DAZZLE-

In 1912 a bill was introduced into the Canadian Parliament authorizing the building, at Canada’s expense, of three battleships of the most powerful type, intended to be vessels of the Queen Elizabeth class. At this period Australia and New Zealand were expending great sums on naval defence, and it was hoped that Canada would decide to follow their example. But Canadian opinion was not ripe for such a drastic departure and the bill for building the three battleships was rejected by a large majority.

There matters remained until the outbreak of war in 1914, when for the first time the “Royal Canadian Navy” appeared as a distinct service in the Navy List. The only warships then owned by Canada were the old cruisers Niobe and Rainbow, but a few hours before war was declared the

Premier of British Columbia bought two submarines which were being built in an American yard at Seattle. This purchase was made entirely on his own responsibility, but it was immediately approved by the Ottawa Government, which offered the boats to the Admiralty.

Manned by expert officers and men from the British Navy, the submarines were speedily placed in commission and co-

At this date it was feared by the people of Western Canada that the powerful German squadron under Admiral von Spee, then known to be at large in the Pacific, might attack their coast. Although the menace did not develop, the mere threat had the salutary effect of bringing home to Canadian opinion the necessity for a more adequate standard of naval defence. As long as hostilities lasted the Canadian press continued to assert that as soon as the Dominion had time to breathe again she would create a fleet more worthy of her status as a great member of the British Commonwealth.

This promise was not to be fulfilled. Canada, however, did make a notable contribution to the Imperial naval forces by establishing a submarine building yard at Montreal, which turned out about a dozen highly efficient submarines. All these craft were completed and crossed the Atlantic to European waters, where they performed excellent service.

Shortly after the war the British Government presented to the Dominion a cruiser, two destroyers and two submarines, which were to form the nucleus of the future Canadian Navy. But in the years that followed, Canada, as with every other community in the Empire, found it necessary to draw her purse-

Year by year the naval budget was pruned until, by 1928, the only Canadian warships left Were two old destroyers and a number of revenue and other Government vessels, most of which were unarmed.

In the following year the first step towards rehabilitating the national navy was taken, for two destroyers were ordered in England. Completed in 1931 as the Saguenay and the Skeena, they are vessels of 1,337 tons with a speed of 35 knots. The design is more or less identical with that of contemporary British destroyers of the Acasta class, except that the Canadian vessels have their hulls specially strengthened to withstand the pressure of ice.

CANADIAN DESTROYER AT MONTREAL. The Champlain, formerly Torbay, was completed in 1919 with her sister ship Vancouver, formerly Toreador. With a displacement of 905 tons, the Champlain has a speed of 36 knots and is propelled by 29,000 horse-

The Royal Canadian Navy of 1936 consisted of four destroyers and three mine-

Although the “South African Naval Service” occupies a page or two in the official Navy List, for all practical purposes it is non-

The average expenditure on defence per head by the Dominions is far below the corresponding figure for the United Kingdom, yet there is no denying the obvious fact that adequate naval protection is just as vital to these outlying member-

The Royal Indian Navy — until recently known as the Royal Indian Marine — may be said to have a history dating back to the beginnings of British enterprise in the East, that is to say, to the early part of the seventeenth century. Not until 1830, however, were the warships owned by the then masters of India, the East India Company, grouped into a regular service officially designated the “Indian Navy”. This force distinguished itself in the Burmese War and in the Mutiny of 1857, but was abolished shortly afterwards on the grounds that the defence of India against a serious attack by sea must needs devolve on the Royal Navy. In 1884, however, the force was revived under the title of the Royal Indian Marine, which was regarded in the first instance as an auxiliary service for the carriage of troops and Government stores rather than as a combatant force.

The Royal Indian Navy

Not until 1914 did the Indian Marine have a chance of showing its mettle. At least one of its ships, the armed transport Hardinge, took-

The Royal Indian Navy is administered by the Navy Office, Bombay, under the Defence Department of the Government of India. Although all the senior officers are Europeans, there is a fair sprinkling of Indians among the juniors. As time goes on the proportion of native officers will, it is expected, be largely increased. The lower deck is manned entirely by Indian ratings, who are excellent seamen and amenable to naval discipline. All authorities agree in declaring the standard of efficiency in the new Navy to be exceptionally good.

Vessels in commission in 1936 include five sloops, a surveying ship and some patrol craft. The most modern unit is the sloop Indus, which was completed in 1935 and took part in the Silver Jubilee Review at Spithead. This vessel and her sister, the Hindustan, are definitely fighting ships, and may prove to be the forerunners of still larger and more formidable Indian men-

Apart from their sentimental and symbolic value, which it would be a great mistake to underestimate, the practical importance of these small but efficient naval establishments maintained by the various Dominions lies in the fact that they constitute an always available reinforcement for the Royal Navy.

Moreover, every fleet forms a nucleus of officers who are thoroughly familiar with the navigation and other conditions prevailing in their special areas, and the value of this expert knowledge was repeatedly demonstrated in the war of 1914-

Finally, as the Royal Navy and the Dominion forces are virtually uniform in organization, training, construction and equipment, they can be merged into one homogeneous whole at relatively short notice.

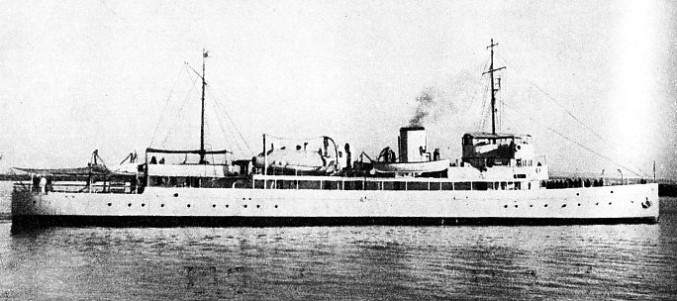

A SOUTH AFRICAN SURVEY SHIP, the Protea was completed in August 1919. Of 800 tons displacement, she has a length of 231 feet overall, a beam of 28 ft. 7 in. and a draught of 7 ft. 6 in. She was armed with one three-

Click here to see the photogravure supplement to this chapter.

You can read more on “Durban”, “Gunboat Patrols in China” and “Singapore” on this website.