© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Fifty Years in Sail (2)

These extracts from the log of the late Captain J. W. Holmes describe graphically his experiences in command of some of the famous sailing ships in the last days of the glorious era of sail

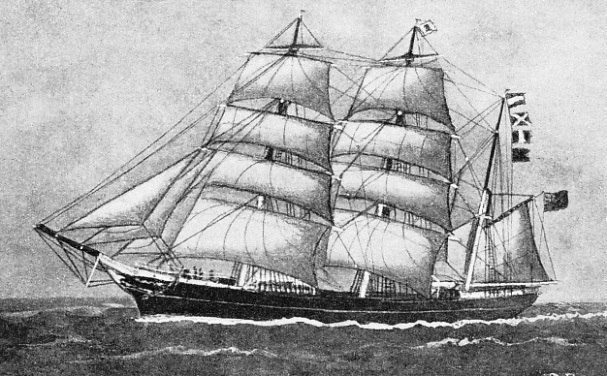

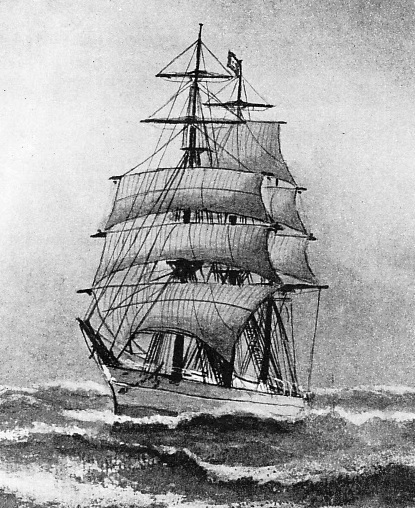

CAPTAIN HOLMES’S FIRST COMMAND was the Leucadia, and his own portrayal of her under full sail is reproduced above. The Leucadia was built at Aberdeen in 1870. A vessel of 944 tons gross, she had a length of 194 ft. 5 in., a beam of 33 ft. 9 in. and a depth of 20 ft. 5 in. She had a figurehead of the Greek poetess Sappho, and her hull was painted green with a yellow band.

THE Leucadia was no stranger to me. I once tried to get a second mate's berth in her, and my uncle, Captain Mearns of Aberdeen, had taken her from the stocks in 1870 and commanded her for ten years before taking over the Romanoff.

The Leucadia was built by Walter Hood and Company for Alexander Nicol and Company of Aberdeen, a firm whom it was an honour to serve. She had for her figurehead the graceful Sappho with the burning lyre, her fingers delicately touching its golden strings. But the lyre and the arms holding it were too dainty for plunging into head seas, so they were made detachable at the elbows and were always amputated before putting to sea.

All her deck work was of teak. Her lower masts, lower yards and bowsprit were of iron, and all aloft and on deck was painted white. Her hull was green, with the yellow stripe, and a very dainty, yacht-

Like so many of her contemporaries, she was built for the tea trade, pathetically late, for the year she took shape, 1870, saw the sailing ship’s doom sealed by the Suez Canal, and now she could scarcely pay her way foraging round the world. She was a splendid ship for going to windward, and could beat any ship afloat on the wind, but not with the wind free.

She would actually go fastest braced up sharp and, though not a fast ship, she was never a hundred days out while under my command. Indeed, her ninety-

It happened thus. After an orthodox passage we reached lat. 20° North, when the north-

This brought us to Queenstown in ninety-

Among them was the Machrihanish, a fine ship which left Taltal two weeks before us, and crossed the Line 2,500 miles ahead of us. While we were in Queenstown she was reported off the Western Isles (Azores) with all sails blown away, and she eventually got in after we had discharged in Hamburg. Among the last arrivals was the Fleur de Lys, which left a month ahead of us and reached Aberdeen after the Leucadia had been six weeks in Hamburg.

This had a momentous bearing on my future — for the Fleur de Lys’s cargo had been bought by an Aberdeen chemical firm, though Mr. John B. Nicol, desirous of bringing an Aberdeen ship to Aberdeen, had strenuously pressed the purchase of the Leucadia’s cargo. “Sorry,” they said, “but your ship’s not fast enough. Besides, she’s leaving a month later than the Fleur de Lys, and we can’t wait for her.’’ Mr. John B. Nicol took a very human delight in pointing out that they had had to wait a great deal longer for the unfortunate Fleur de Lys, and as the outcome of this I was summoned to Aberdeen and given command of the Cimba.

The iron ship Cimba was built in 1878 by Walter Hood of Aberdeen, who built all Nicol’s ships except the Yalleroi, Torridon and Gostwyck; the Cimba, like the Leucadia, was painted green with a yellow stripe, with white paint on deck and aloft. Her figurehead was a lion, from which she took her name. The red lion rampant was also Nicol’s house flag.

Unlike the Leucadia, she had no lost hopes to mourn, for she was never on the China trade. From her first till her last three voyages she was always a wool clipper, and over the whole of her twenty-

She had only two British masters, Captain Fimister — who took her from the stocks — and myself, who had her from 1895 till 1906. She was heavy aloft, and narrow, and this made her extremely tender; but she was very pretty, and much beloved by both her skippers, and certainly by most of the men who sailed in her. She was good on the wind, but not as good as the Leucadia, which was indeed the super ship, a miracle on the wind.

On my first outward trip we experienced little of note till we passed the Cape, when we suddenly struck a gale with the heaviest sea I have ever seen in my life. It was a perfect, clear, sunny day, with a bright blue sky, but at 4 a.m., when I came up on deck, it started howling like all the demons let loose. I shortened down to main topsail, low topsails and foresail; but she raced before the wind like a thing possessed. Mountainous seas were running after the ship and she covered 336 miles that day, averaging 16-

But there was fiendish purpose and cruel tragedy in those diabolic curling waves, for one of them took my second mate and no one knew the going of him.

In 1896 she did the trip home in seventy-

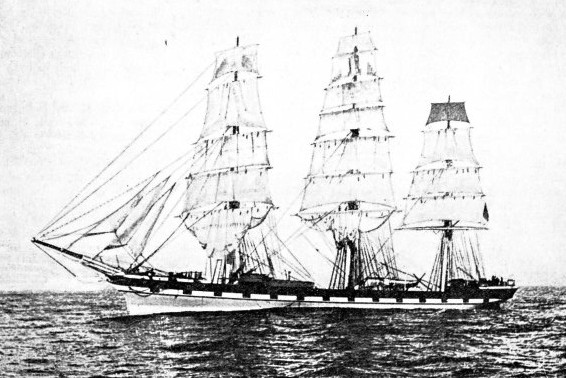

BOUND FOR SYDNEY in 1909, the Port Jackson left London on the same day as Captain Holmes in the Inverurie left Belfast. Although Captain Holmes thought it would be impossible to keep near her, the Inverurie arrived in Sydney on January 10, 1910, only ten hours behind the Port Jackson. A vessel of 2,212 tons gross, the Port Jackson (left) was 286 ft. 2 in. long, with a beam of 41 ft. 1 in. and a depth of 25 ft. 2 in.

Coming home in 1898 we fell in with a Shire steamer in about lat. 57° South, long. 100° West, and kept her in company for several days, eventually reaching London only one day behind her.

My third voyage was to Brisbane for wool, and this was the first time the Cimba had ever missed Sydney Harbour. We loaded near Government House and Lord Lamington, the Governor of Queensland, often came aboard to lunch or yarn. He was keen on things nautical, and made very good company. On her fifth voyage, the Cimba again missed Sydney, ranging as far as Rockhampton and Brisbane in her quest — so elusive was the Golden Fleece becoming for its early carriers — and we left Brisbane with a bare ninety-

It was touch and go to the very last, for we got stuck outside the Channel with easterly winds and hazy weather. I made in close to the Scilly Isles, and the day before our time was up I stood in to the Bishop’s lighthouse to report, and, seeing that everything depended on this, I stood in till I could see the lighthouseman.

But remembering the occasion when our signals were not reported, I stood off all night and at 8 a.m. stood in to St. Mary’s signal station till I saw the answering pennant. It was well I did so, or the sales would have been lost after all, and one-

On my eighth voyage, in 1903, the dainty little Cimba for the first time left the track of the wool clippers, for on discharging at Brisbane, she went in ballast to load barley at Valparaiso.

It was there, on June 3, that I put in the very worst night I have ever experienced at anchor. From 8 p.m. to 8 a.m. a northerly gale blew with increasing fury, and with thirty or forty ships at anchor in that open bay, exposed to the full force of the Pacific, the night was rent with signals of distress, which could not be answered. No one knew which would be the next cable to part, or who would survive the night, and morning revealed a piteous sight.

A Career Without a Casualty

The fine ship Foyledale of Liverpool was blown ashore with great loss of life. Two Chilean ships were dashed to pieces on that forbidding shore, while of the Pacific Mail steamer Arequipa not a trace remained. She had gone down with all hands.

The Cimba could not have held out much longer. She was dragging till she was under the bows of an Italian ship. On shore the toll of disaster was also high. Great stone blocks from the sea-

My ninth voyage in the Cimba, to Sydney, must have been my record for fine weather. From outside the Channel to Tasmania I only had the royals in for one hour. I never reefed a topsail in the Cimba; and on my first and second voyages I went from Sydney to Dungeness without taking in the main top-

During all the years I was in command I was very fortunate in having good weather and good crews; and it is a comforting reflection for a man who has spent fifty-

I always had good gear, and I had officers and men who could be depended upon. Many of them sailed with me voyage after voyage (one indeed, for twenty years), and they each had a personal pride in the ship’s achievement, and perhaps some faith in her skipper — for we had no grousers on board even when driving through the vilest weather, and we always found time for diversions in fine weather.

LONDON TO AUSTRALIA IN SEVENTY-

Wrestling and boxing contests were popular, and the boys were quite good at staging impersonations of Captain Kettle, while music from fiddle, accordion or mouth-

On her last voyage the Cimba loaded for Sydney, and it seems fitting that the little wool clipper, so well known in Sydney all her life, should make her farewell to Sydney when she was, all unwittingly, so near the end of her career. Destiny was surely foreshadowing her doom in sending her to Newcastle to load coals for Callao (Peru). It was the first time the dainty, yacht-

She discharged her nitrate in Rotterdam. Then the blow fell. Mr. G. W. Nicol, the sole surviving partner of the firm, died suddenly, and all the ships were sold. So passed one of the best firms of shipowners, and another beautiful ship went to the foreigners. The Cimba herself found a grave in the Gulf of St. Lawrence some years later, and perhaps it was a better fate than that reserved for so many beautiful ships, which, as freights became ever more elusive, were dismantled for coal hulks, and condemned to lie forgotten and forlorn, a very travesty of their former pride and beauty. The ignominy of such an end is more cruel than the merciful oblivion of the waves.

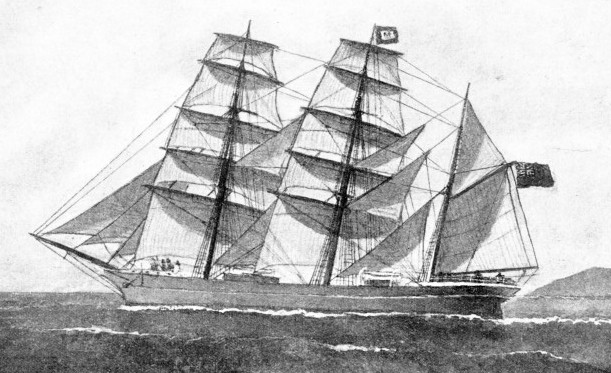

UNDER FULL SAIL, the Invergarry is well portrayed in the painting by Captain Holmes from which this picture is taken. On June 2, 1914, Captain Holmes sailed her from Newcastle, New South Wales, with a cargo of 2,356 tons of coal for San Francisco, but for a month she lay near the port becalmed. Meanwhile, war had broken out and two German warships were looking for her. Fortunately the becalmed Invergarry secured a tow and reached safety unmolested.

With the outgoing of Alexander Nicol and Company there passed the last fleet of sailing ships famed for their beauty; for later owners built for freight in the days when freights were becoming increasingly hard to obtain. Carrying power was of greater importance even than speed, and economy was the greatest consideration of all. The beauty of line, the heavy spars, the teak and brass deck work, the exquisite finish, the evidence of builder’s pride in every detail — these are lacking in the later ships.

A Losing Fight

Sufficient for them if they could hold their own and pay their way — and right gallantly they did it. Against increasing competition, against increasing expenses, against the hungry, devouring monsters of modern steamships, they held their superb way, gathering the crumbs of cargo from many corners of the earth.

Among these modern sail carriers were the fifteen ships of George Milne and Company of Aberdeen, whose barque Inverurie I next commanded. The Inverurie was built by Alexander Hall and Company of Aberdeen, the builders of the Yalleroi and the Torridon. She was steel built, of 1,309 tons register, and carried 2,230 tons. Everything about her was of the lightest steel — deck houses, masts and yards. The Inverurie was the first steel ship Milne’s had, and so she was the commodore of the fleet being built in 1889. She had a woman as figurehead, and was painted slate-

On my first three trips in the Inverurie I made the land at the same hour on the same day, on the third occasion reaching Fremantle (Western Australia) from Garston (Liverpool) in eighty-

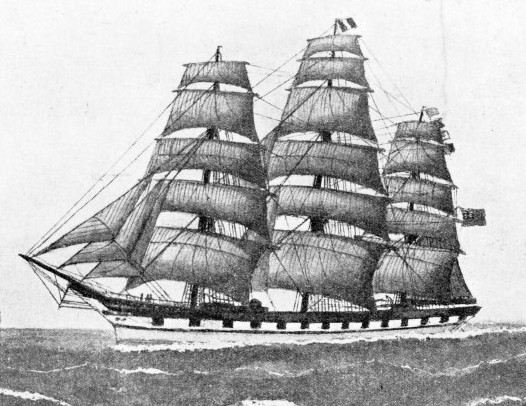

“ONE OF THE GALLANT OCEAN WHIPPETS” is how Captain Holmes described the Glenfinart. She was built at Glasgow in 1876, and was a vessel of 1,601 tons gross. Her length was 254 ft. 2 in., her beam 33 ft. 6 in. and her depth 23 feet. For long she maintained a regular service to Montreal with clock-

In 1909 we left Belfast for Sydney on the same day that the Port Jackson left London for the same destination, and the mate remarked that the boys had a bet that we could do as well as she. “Nonsense!’’ I said. “This ship couldn’t look at the Port Jackson.” With the Cimba such a challenge would have found plenty of cheerful backers.

Nevertheless, the Port Jackson reached Sydney at 10 p.m. on January 9, and the Inverurie arrived at 8 a.m. on January 10 — but ten hours between them. For this performance the owners handed me a bouquet, and I gave the ship a celebration. On the way home we spoke the Inverlyon, formerly Nicol’s largest ship the Gostwyck, and we kept her in sight for four days.

In 1910, on the voyage home from Port Wakefield (in the St. Vincent Gulf, South Australia) with wheat, we experienced some of the vilest weather I have ever known. On May 19, in long. 159' West, lat. 50° South, we ran into a hurricane which lasted till June 4, undoubtedly the longest spell of inexpressibly beastly weather in my experience, for it was just one long unmitigated horror without a sign of a break.

For the whole time we were running for dear life under two lower topsails only, with fifty times too much wind, snow and lightning day and night, pitch darkness alternating with hellish lightning which tore the heavens open with blinding flash and left intensified blackness — such blackness that for sixteen days we could not see a man on deck. And during the whole sixteen days the devouring seas following us were curling up behind like mountainous canopies, and it was only the fact that she was stripped down that saved her from having her decks swept clean. Every-

Refloated After Twenty Years

We rounded the Horn on June 10. On my last trip in the ship we were celebrating Boxing Day with sports, when we fell in with the Welsh ship Celtic Glen, which passed quite close to us in lat. 48° North, long. 28° West. Her men were chipping iron rust, and doubtless thought our crew were all mad seeing them skylarking about at sports.

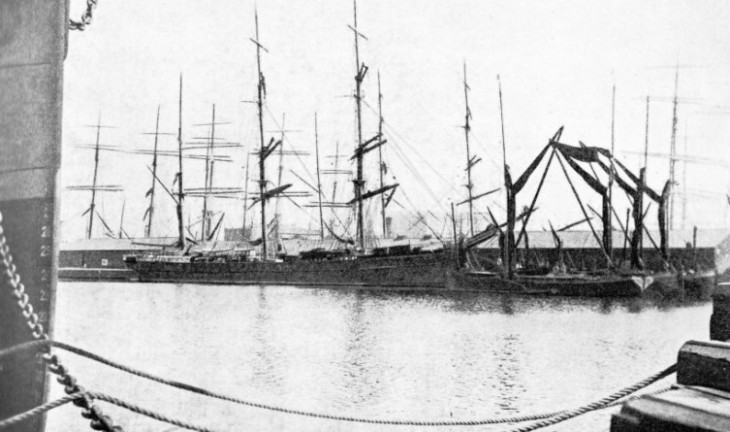

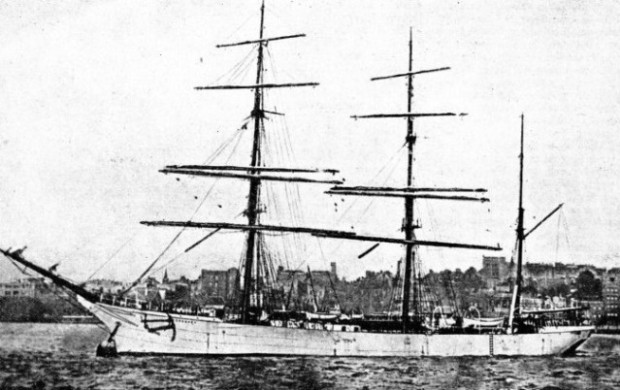

WITH SAILS FURLED. This photograph of the Invergarry is a striking contrast to Captain Holmes’s painting of her under full sail. The Invergarry was built at Dumbarton in 1891 and was a vessel of 1,416 gross tons. She had a length of 237 ft. 6 in. between perpendiculars, a beam of 36 ft. 2 in. and a depth of 21 ft. 6 in.

On arrival home I was transferred to the Invergarry which, though excessively plain, was better looking than the Inverurie about the decks, but not so strong a ship. Only ¼-

She was the four-

Built at Southampton in the 1880s, she was taken from the stocks by Captain Campbell, my cousin by marriage, and was then the largest ship afloat, being 2,646 tons register. I saw the Andrina on her maiden trip in Sydney when I was there in the Blackadder and, strangely enough, I saw her after her resurrection, in Buenos Aires, for she sailed into port on the same day that I did, on the last voyage I made. She was then a Chilean, named Alejandnna.

We left Newcastle, New South Wales, on June 2, 1914, with 2,356 tons of coal for San Francisco, expecting to arrive there at the beginning of August. Little did we dream that the world catastrophe was timed for the same date. Nor could we realize that we should thank our lucky stars for all our bad luck, when the wind fell away to dead calm and we could make no headway. For about a month we lay becalmed and befogged, and when, on September 1, I sighted an American tanker, El Secundo, I signalled her, asking my position, as I had not seen the sun for nine days.

He gave it — adding, “Do you know your country is at war with Germany? And there are two German cruisers round here, been looking for you for the last month. You’d best get within the three-

It was good advice, but quite useless to a becalmed ship. However, the American backed it with practical assistance, for he wirelessed my position to San Francisco, and a tug came out to meet us.

We left San Francisco on October 22 with 2,300 tons of wheat and barley, and this time there was no difficulty in getting a cargo. The difficulty was in delivering it.

A CONTEMPORARY OF THE CIMBA, the Argonaut left Sydney with the Thessalus and the Cimba, under the command o Captain Holmes, on the same day in 1896, The Cimba reached London in seventy-

I got my wheat to Queenstown and then to Grimsby without other incident than the narrow shave from a torpedo off the Isle of Wight — and then I offered my services to the Admiralty in any capacity, as did almost my entire ship’s company. Months rolled on and nothing came of my application, and a further effort elicited the information that I was over age.

But I was not then so old as when I took up my next command in 1920. I had by that time given up all thought of further command, so few were the sailing ships left, but on March 31 I received a telegram from an old acquaintance, Captain Rugg, who had commanded the Neotsfield and during the war had been trading between Bunbury (Western Australia), Mauritius and Singapore in the barque Dee until she was sunk by the German raider Wolf off Australia in 1916.

In 1920 Captain Rugg was taking out a schooner, the Gardner Williams, to his owners in Mauritius to replace the Dee; but he was now so ill through his two years’ internment in Germany that he had to put back into Holyhead and wired me to take over his command. Thus it came to pass that my sea-

My latest and last command looked ludicrous to a man who had spent all his life in square-

The Gardner Williams started origin ally to get a charter from Buenos Aires at £7 a ton, but freights were dropping every day, and eventually she went in ballast from Buenos Aires to Capetown to get coppered, as there was then no coppering to be had in England. After this we proceeded to Bunbury in thirty days, and there we loaded timber for Mauritius, which we reached in thirty-

After handing over the Gardner Williams in May 1921, I returned home round the old Cape route, for the first time in my life as a passenger. Yet ere I write “Finis” to this story, I would recall with pleasure those many shipmates of mine — skippers under whom I served with pleasure and respect, fellow skippers whom I met in many waters, and all the officers, boys and men who so loyally served me. I would also salute those of the great brotherhood who have made their Last Port.

Finally, I would pass on these memories to the sailors of to-

A DAILY AVERAGE OF 146.5 MILES was maintained by Captain Holmes in the Inverurie during an eighty-

You can read more on ,

“Romance of the Racing Clippers” and

“Thermopylae and the Cutty Sark”

on this website.