© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

French Shipping

Few maritime nations can claim a mercantile marine history as proud as that of France. French shipping is of great diversity, ranging from fine Grand Banks fishing fleets to fast transatlantic liners

SEA TRANSPORT OF THE NATIONS -

TH E French Merchant Service is one of the oldest and most interesting in Europe, or in the world. More than half the borders of the country are on the sea and the coast-

E French Merchant Service is one of the oldest and most interesting in Europe, or in the world. More than half the borders of the country are on the sea and the coast-

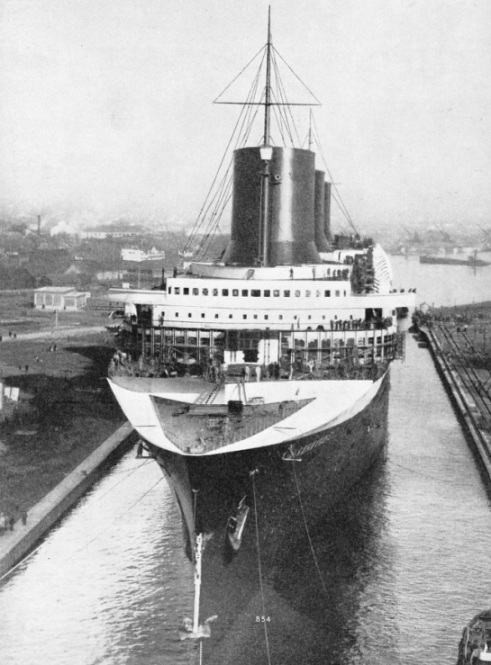

A GREAT TRANSATLANTIC LINER, the largest vessel under the French flag, presents an imposing sight as she is towed into dock. The Normandie has a gross tonnage of 86,496 (figure revised in May 1936). She was completed in 1935 at St Nazaire, at the mouth of the Loire, for the Compagnie Generale Transatlantique.

When they have had dealings with the sea they have shown much fixity of purpose and continuity of thought. Policies worked out centuries ago are still functioning well to-

The real basis of regular French shipping is, perhaps, the wine trade, although it would appear that French ships were going overseas before the beginning of the Christian era. There was certainly a trade between the northwest coast of Gaul and Britain long before the Romans reached the shores of the English Channel, and there is no reason to believe that Marseilles had forgotten the traditions of the Phoenicians who traded with that flourishing Greek colony.

There was a regular wine trade between France and England for many years before the fifth century. For a long time the use of wine was restricted, but as wine drinking developed the trade grew to considerable dimensions and had a great influence on the civilization and lives of the Saxons.

After the Norman Conquest, Franco-

long time before English ships had attained a standard which let them take their proper share of the business.

At a period when the commerce of the world was enjoying what was perhaps its greatest opportunity of expansion, in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, France was exceedingly lucky to possess two men of outstanding merit who made every difference to the chances of French shipping. Maximilien Sully (1560-

As one instance out of many, the question of personnel may be taken. In Great Britain, whose shipping and Navy meant her very existence, this subject was left virtually without consideration until the passing of the Merchant Shipping Act in 1854. Merchant seamen were engaged without reference to their previous experience and turned away when their services were no longer required. A captain could ascertain the character and ability of the men that he had signed on only when the ship was at sea and there was no opportunity of making any change.

In the general disorganization many owners exploited the men wickedly and in return the men became mutinous or turned pirate at the first opportunity. Even the Navy was manned in the same casual fashion. There was no continuous service, and when a ship wanted men she invited volunteers and made up the balance with the Press Gang. The King’s service became the refuge of vagrants and gaol birds. Landsmen who had no idea of the sea were gathered in thousands by the Press Gang and died in hundreds. At the end of every commission they were thrown back on to the streets, trained and untrained alike, and the whole business began over again as soon as another ship wanted a crew.

In contrast to this, Colbert founded the Inscription Maritime (Register of Seamen) in 1663. He fully realized that, in the constant wars between the two countries Great Britain had the advantage of a truly seafaring population, many of the inhabitants living within sight of deep water. He determined that France should make up her deficiency by organization. Under the Inscription Maritime a proper register was kept of the whole male seafaring population between eighteen and fifty years of age. The men on this register were not to be taken for the Army but were always to be available for naval service.

Their terms of employment in commercial ships were, to a degree, regulated to their advantage, and when their working days were done they were not faced with the nightmare of poverty as British sailors were, but were sure of a small pension, sufficient for the needs of a thrifty Frenchman. In the course of nearly three centuries it is only natural that the details of this scheme should have been altered as circumstances changed, but the spirit and general framework remain and are still of great service to the countrv. By it French ships are manned entirely by Frenchmen, desertion is almost unknown, the inshore fishing population is kept virtually intact and the French Navy is always certain of a number of recruits who have known how to handle boats since childhood.

It is the French Colonial Empire which has always had most influence on French shipping. The French have never cared much for the carrying business between foreign countries that made the shipping prosperity of the Dutch and the British. Former French colonies in India and North America, lost in war, have been replaced by vastly bigger ones in Africa, the Far East and the Pacific. These colonies are of great importance to France and French shipping is of the greatest importance to them. The foundations laid in the seventeenth century, when the French East Indiamen were the rivals of the British and generally their superiors on technical points, exist to-

It is not merely in the carriage of merchandise that French shipping has made for itself an important place. In gathering a harvest from the sea the country has always been conspicuous, and it is so to-

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries these same hardy seafarers were the pioneers in developing the cod fisheries of the Grand Banks. Cape Breton, the oldest French name in the North American Continent, is still a living testimony to the enterprise of those old-

Although the fleet gets smaller and smaller every season, the fishermen of the north-

An Emperor’s Lead

The first of these auxiliaries owed nothing to her predecessors in the matter of appearance, and there now seems to be every hope that the French sailing Grand Banker, and the magnificent type of mariner who takes her to sea, will have a prolonged lease of life. When the sailing fleet sets out from the Breton ports its departure is always made the occasion of a religious ceremony which is as impressive as it is picturesque.

Even the Emperor Napoleon I, essentially a soldier as he was, realized that the permanent prosperity of France must rest on her overseas trade. In 1812 he created the Ministry of Commerce, with a special department for the maritime side, long before such a departure had been considered in other countries. His idea found firm root, and flourished through all the revolutions and counter-

Whatever faults the Emperor Napoleon III may have had as a ruler, there is no doubt that he appreciated the merchant service, and the necessity of a navy to protect it, far more than most monarchs. It was largely due to his efforts that the services which are still maintained by the Messageries Maritimes and by the Compagnie Generale Transatlantique, owners of the Normandie. Were established with sufficient subsidy to enable them to overcome economic difficulties. At the same time Napoleon III took full advantage of the Inscription Maritime to build up a first-

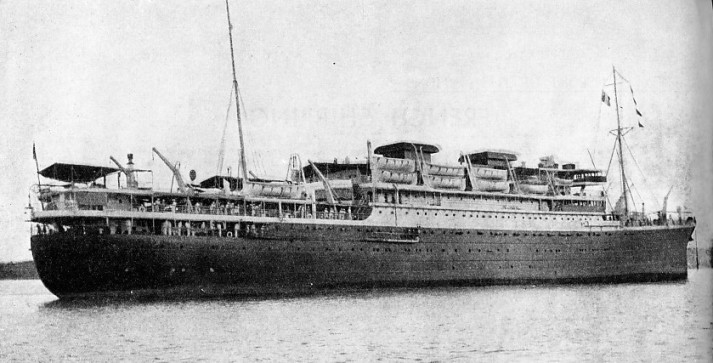

A SHIP WITH SQUARE FUNNELS is an unorthodox vessel, but French shipbuilders do not hesitate to deviate from tradition when they consider it advisable. The Marechal Joffre is a twin-

There were many difficulties in his way, and many vested interests to be overcome, but he maintained his principles with pertinacity and insisted on the State providing subsidies where they were necessary. He was not the originator of this system. The Government had followed it at intervals since 1783, when it established the first mail contract between Europe and New York, but the policy had not been continuous, nor was it so for some time afterwards.

It was in the year 1881, when many changes had been made in the commercial world, that the French started the regular system of State aid which distinguished their shipping for many years. Many of the old forms were continued, some were amended and some entirely new were introduced. It was an absolutely comprehensive bounty law and, with alterations from time to time to meet altered circumstances, it lasted until the end of the war of 1914-

In addition to this bounty for shipping and shipbuilding, France for years has had coastal protection, only French ships being allowed to ply within coastal limits. The definition of what constitutes such limits has always been a vexed one. The United States interpret them widely, but in France they cover only the coasts of the homeland, and the route between France and the Northern African territories of Algeria, Tunisia and Morocco, which, it must be remembered, are not regarded as colonies but as departments of the mother country.

One of the most striking effects of the subsidy system was the remarkable increase in sailing tonnage, although the laws were framed to encourage steamers of the most modern type.

Subsidized Sail

Between 1893 and 1901, at a period when the sailing ship tonnage of every other country was decreasing rapidly, that of France increased from 396,582 to 564,447 tons. This, curiously enough, contributed greatly to the total disappearance of sail. Under the subsidy a sailing ship often found herself able to go from one end of the Earth to the other without a ton of cargo and able to show a good profit at the end of the voyage, useless to the flag as it must have been. Magnificent ships were built and, having already made their profit, were willing to carry cargo for next to nothing. The ships of other flags could not compete with this, so large numbers were hurried to the scrappers. Then after 1918 all bounties were stopped for a time, and the magnificent fleet of French sailing ships melted as if it had been snow in a sudden thaw.

During the war of 1914-

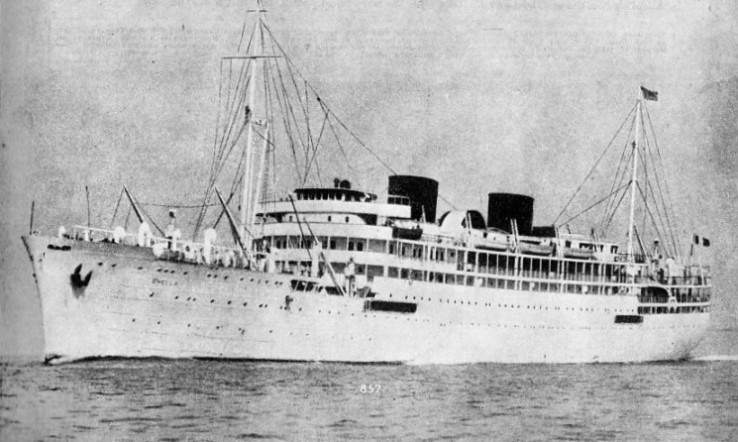

ONE OF THE SPLENDID FRENCH LINERS that operate from Marseilles. The shapely stem and stern of the Chella, about 9,033 tons gross, are impressive and her white hull stands out in contrast to her dark, squat funnels. The Chella was completed in 1934 and is 426 feet long 62 feet in beam and 37 feet in depth. She belongs to the Compagnie de Navigation Paquet.

There was no longer a heavy subsidy at almost every turn to help over difficulties. The general system of bounties was brought to an end, but special contracts were arranged with such companies as the Messageries Maritimes and the Compagnie Generale Transatlantique. These contracts were for the maintenance of mail services needed for Imperial purposes in peace, and of an adequate reserve of ships which could be commissioned as cruisers in the event of a future war. Nearly all the mail services which are in any way advantageous to France are thus maintained. There are special arrangements for certain services such as the communications with North Africa, where the Government has built fast and powerful ships suitable for cruiser work and has an arrangement with the companies to manage them.

Special circumstances also arose for the Compagnie Generale Transatlantique. That historic French Company, which has a high reputation on the North Atlantic and which also maintains other services, had laid down a giant ship, later to be the Normandie, just as the Cunard Company had laid down the Queen Mary. Whereas the British company was forced to suspend building for a long time during the financial crisis, the French authorities did not hesitate to come to the assistance of the Compagnie Generale Transatlantique, permitting the Normandie to be completed without interruption and maintaining the services.

The State assumed a certain measure of control in the company’s affairs, but paid generously and helped in every possible way. Perhaps the help has been dearly bought at the cost of having State officials with no previous shipping experience influencing the decisions of some of the ablest shipping men in the world. The company, however, was able to carry on its services undisturbed and the Normandie was completed to break the record and to enjoy a spell of Atlantic service almost without a rival. These extraordinary measures were not the only steps that the State had to take during the worst part of the slump. In the summer of 1934 the Tasso Law came into effect -

So the tricolour is still proudly worn by a large number of ships. Occasionally their design may seem bizarre to the eyes of the more orthodox Englishman or American, but French naval architects and engineers have a high reputation for ingenuity and technical achievement.

Owners of the “Normandie”

Among the principal companies are the Compagnie Generale Transatlantique, the Messageries Maritimes, the Compagnie Sud Atlantique, the Chargeurs Reunis, the Paquet, Mixte, Fraissinet and Fabre Companies, with many others. There are a number of concerns in the cargo trade with only one or two ships each. Colliers and tankers exist in their reasonable proportion.

The Messageries Maritimes popularly include two distinct but allied concerns. The original company dates from the days of Napoleon III and until 1912 was interested largely in the South American trade. After that its activities were concerned with the Mediterranean. Indian Ocean, Far East and Australia, many of its sailings being under contract with the Government, which, in

return lor the subsidy it paid, laid down strict conditions. By 1921 things had changed so much at sea that it was quite impossible to do all that had been arranged in 1911, especially as nearly half the company’s passenger fleet had been lost in the war of 1914-

The two concerns have been among the greatest enthusiasts for the oceangoing motor ship in France and have had some fine examples built. The Marechal Joffre, of 11,732 tons gross, which is illustrated above, is one of them, and her rather bizarre appearance does not reduce her efficiency. The Aramis (17,368 tons) and the Felix Roussel (16,774 tons) are bigger.

The fleet of sailing ships that was once so extensive is now reduced to a few small coasters which are often to be seen in the British coal ports of South Wales, a sizeable coasting fleet in the Mediterranean, the still fine fleet which crosses to the Grand Banks, and the numerous fishing vessels. A number of these still retain sail with various rigs and refuse to be standardized by motors. Considering the pioneering work that the French did with the internal com bustion engine on land it is curious how slowly it was adopted at sea, but all that is changing now.

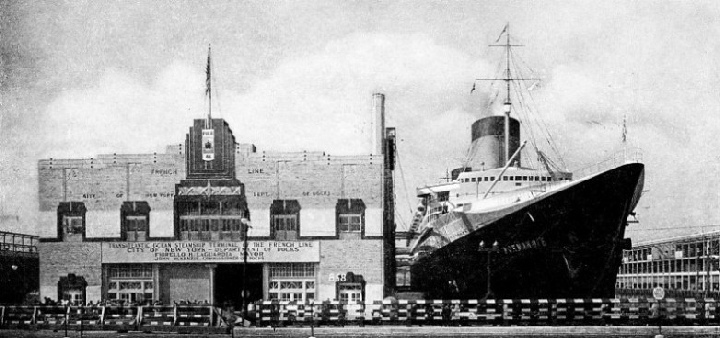

FAMOUS OCEAN GREYHOUND at the Transatlantic Ocean Steamship Terminal of the French Line (Compagnie Generale Transatlantique) at New York. The shapely bows of the Normandie dominate the scene at the entrance to Pier 38, where she is berthed. Launched on October 29, 1932, the Normandie broke the existing speed record on her maiden voyage of four days, three hours and two minutes. Her average speed between Bishop Rock Lighthouse, Scilly Isles, and the Ambrose Light, New York was 29·9 knots.

You can read more on “The Blue Riband of the Atlantic”, “The Chella”, “The French Navy” and

“The Triumph of the Normandie” on this website.