© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Fruit-Carrying Ships

The carriage of fruit presents special problems to the shipowner, for it is impossible to mix citrous and non-

ROMANCE OF THE TRADE ROUTES -

WHITE-

TO most of us the Caribbean Sea, with its palm-

But Romance is not dead, for the Caribbean now is the home of a trade which is almost world-

The Caribbean Sea is one of the centres of the banana trade, the converging point of the routes of the fleets owned by the United Fruit Company and others. It is. one of the king-

Until recently few fruits could claim to have fleets of ships devoted exclusively to their transportation, and in this respect the banana was predominant. Its importance is still undeniable, but its predominance is now shared by citrous fruit and by deciduous fruit. The civilized world, with the possible exception of America, does not normally employ the banana as a breakfast food, but uses it lavishly for dessert purposes. People do, however, demand grape-

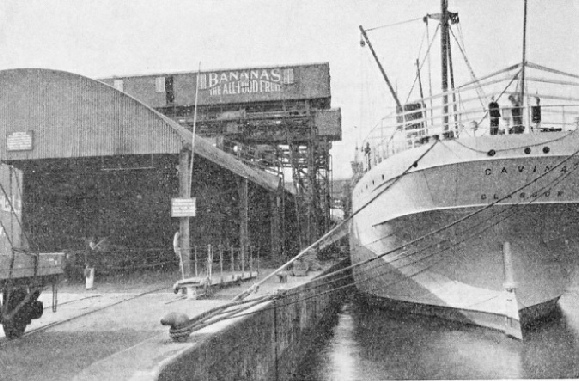

AVONMOUTH DOCK in the Port of Bristol, is one of the busiest centres of the banana trade in Great Britain. Here Elders and Fyffes’ banana ships discharge their cargoes. The Cavina, a twin-

The trade started because an enterprising New Englander, Lorenzo D. Baker, returning to Boston in the Orinoco, called in at Morant Bay, on the picturesque and fertile island of Jamaica, to collect bamboos for paper making. More out of curiosity than for any other reason he took back a few bunches of bananas with him. These proved so profitable that he resolved to make several trips a year to Port Antonio, in the same island, with the 120-

Later more vessels were added and the firm of L. D. Baker and Company was formed. This later became the Boston Fruit Company and finally the United Fruit Company, which now owns plantations, wharves, sugar mills and refineries, passenger ships, hotels and radio service. It is an organization with branches in half the capitals of Europe. Directly or indirectly it has stimulated the building of hundreds of thousands of pounds worth of ships, not only for its own use but for other branches of the fruit trade. The story conjures up a romance as big as that of the Charter Companies of the old days of sea venturing.

The banana cannot endure the presence of any citrous fruits in a cargo. If bananas are left in an ordinary dessert dish in the presence of oranges or apples, the bananas go black and bad. This is because the oranges and apples “breathe” out a form of acid gas that the banana cannot stand.

As a harmless domestic tragedy this is a matter of little or no importance, but its effect upon shipping is far wider, because bananas and oranges cannot be carried in close proximity in ships. The difficulty has not arisen until recently, because, compared with the banana, the grape-

The fruit transport business falls under two main heads -

The fruit transport business falls under two main heads -

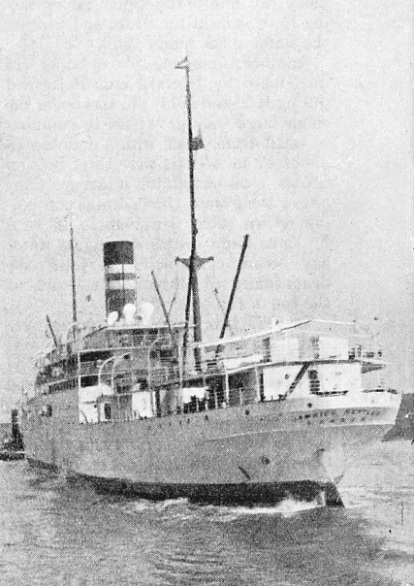

SLEWING ROUND to enter the East India Dock, London, where the cargo of bananas is discharged. The Jamaica Settler was built in 1910 at Birkenhead as the Highland Laddie, and originally designed as a meat carrier. She was a vessel of 7,256 tons gross, with a length of 405 ft 9-

In addition there are many local grades, some of them of no little importance, such as that between the Fiji Islands and Australia. The Mediterranean, too, is a fruit source of increasing importance -

“Temperamental” Fruit Cargoes

The fruit holds are cooled by what is known as surface ventilation from large cowl ventilators on the deck, or by fans drawing their air from the deck and distributing it over the holds through light steel trunking. This is quite satisfactory even although the conditions for carrying bananas are so different from those pertaining to other fruit cargoes.

Bananas, for example, must ripen during transit, and they require not only different temperatures but also different methods of stowage from other fruit cargoes. They are that rare kind of cargo which can be loaded by an endless belt system with pockets in it and unloaded by the reverse process of a similar machine. Bananas were among the first refrigerated cargoes to be carried generally after the original introduction of refrigeration for meat.

Until recently, if a shipping man referred to a fruit ship, he meant a banana carrier. Until that time the refrigeration was more or less of a crude nature, requiring the fitting of machines for cooling air in cooler-

The contrast between the banana ship’s refrigeration and the meat carrier’s is mainly in that whereas one circulates cooled air, the other cools brine and pumps it in its cooled condition through nests of pipes or grids on the undersides of the decks.

Year by year with the addition of more “temperamental” cargoes of fruit to the world’s trade routes, refrigeration processes become more and more scientific. It is possible now, for instance, to control not only the temperature of a hold but also the gas content. Citrous fruits, for example, breathe rather unpleasantly and may taint other fruits with which they come into contact. It is thus an advantage to be able to control the “make-

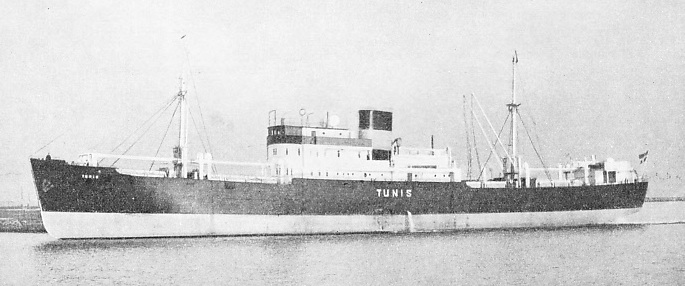

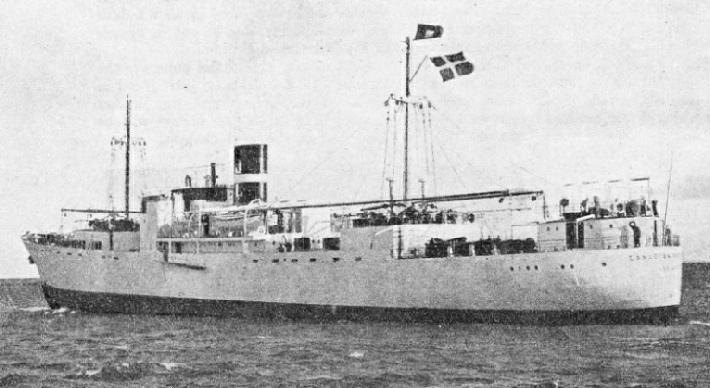

BUILT IN 1935 for the United Steamship Company of Copenhagen, the Tunis, 1,450 tons gross, is specially designed for bringing Western Mediterranean fruit to North European ports. In addition, this ship has comfortable accommodation for a number of passengers and her holds are capable of carrying general cargo. She has a length of 270 feet, a beam of 40 ft 4-

All this is part and parcel of the fruit ship, and thousands of pounds are spent yearly upon research for the production of more and more perfect machines for the carriage of the more delicate fruits from South Africa and California. For while the technique of banana carriage is not static, it is older than that of the carriage of citrous and deciduous fruits.

As with so many other trades of paramount importance, the citrous and deciduous fruit trade became possible with the develop-

New Ship Type in 1934

The Panama Canal became the outlet to Europe, but there was no refrigerator tonnage available and the produce of the Pacific Coast had to be canned. California even to-

Soon after the opening of the canal big cargo liners running from Europe to the Pacific North-

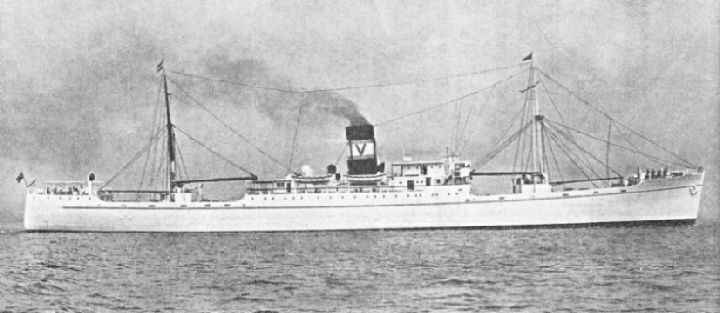

A MODERN DANISH FRUIT-

Since 1934 many such ships have been built. In design they are highly-

Fruit is a seasonal cargo and the modern fruiter, which is so designed as to be able to carry either citrous fruit or bananas, follows the fruit seasons round the world, getting charters now for a voyage, now for a. season, bargaining with owners and growers for the opening up of new routes. The modern fruiter is always speedy and, thanks to modern marine engineering, is likely to become speedier.

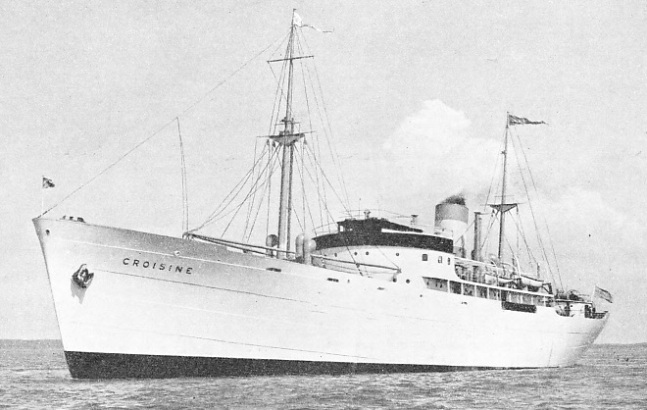

THE CURVED SUPERSTRUCTURE of the Croisine is a pleasing feature in the design of a modern fruit-

Such vessels may run one way “light” without fruit, or at the best with as much general cargo as they can pick up. They offer excellent accommodation in rooms, with bath and an excellent cuisine for twelve passengers. A typical fruit-

One of the largest firms in the banana trade, Elders and Fyffes Ltd, owns a fine fleet of banana ships. This fleet is employed on regular services from Avonmouth, Garston (Liverpool) and Swansea to Jamaica and Trinidad, to other islands in the Caribbean and to the mainland of Central America. One of the larger and more recent vessels on this service is the Toltec, 5,502 tons gross. She is 388 ft 9-

Banana ship or citrous carrier, many of the characteristics are common. Either type of vessel has the largest possible number of decks and the smallest possible number of bulkheads. The ships must be of medium size and have a speed in service loaded of at least 15 knots. The maximum number of decks is necessary because it assists in the carriage of the greatest amount of fruit on given dimensions. The minimum number of bulkheads prevents the fruit space from being split up into small compartments, each with its own problems of ventilation and stowage.

Otherwise, in her internal division the fruit ship resembles the oil tanker. In the fruit ship the holds must be gas-

Mosquito-

A typical important fruit port is Puerto Barrios, on the Caribbean side of the Republic of Guatemala in Central America. A dirty mosquito-

The modern fast fruiter has two tiers of ‘tween decks underneath the main deck forward and aft of the machinery space amidships. In addition there is a long forecastle, which is sometimes brought aft to join with the centre superstructure to secure extra space for fruit carriage. When this is done part of the forecastle is insulated also. The modern fruiter is streamlined with raking bow and curved superstructure front. A modern fruit ship, the Gap des Palmes, with a length of 330 feet and a beam of 44 feet, has a deadweight capacity of 1,950 tons when loaded down to 18 feet. Her fruit capacity in four holds and ‘tween decks is 153,750 cubic feet. She has a fuel-

All kinds of machinery are used for fruit ships. Most vessels under the British flag have steam reciprocating engines and Scotch boilers, America favours turbo-

Fruit ships can usually be recognized at sea by their clean modern appearance and grey or white hulls. The great fleets of fruit-

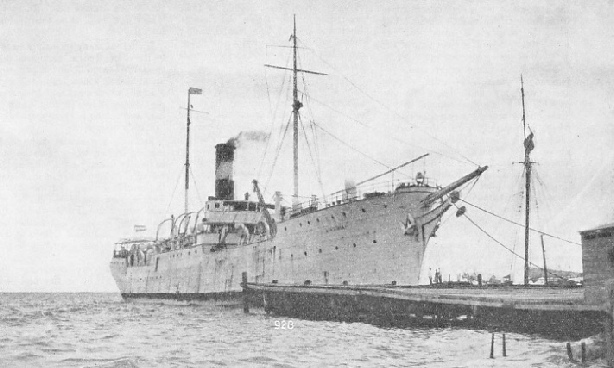

AT KINGSTON, JAMAICA, the fruit ship Virginia is shown in the photograph below coming to her moorings. Built in 1904, and operated by the Standard Fruit and Steamship Company, the Virginia is a vessel of 1,636 tons gross. Her length is 265 feet, her beam 36 feet and her depth 13 ft 9-

AT KINGSTON, JAMAICA, the fruit ship Virginia is shown in the photograph below coming to her moorings. Built in 1904, and operated by the Standard Fruit and Steamship Company, the Virginia is a vessel of 1,636 tons gross. Her length is 265 feet, her beam 36 feet and her depth 13 ft 9-

You can read more on “Development of the Oil Tanker”, “Filling the Ship” and “Refrigerated Ships” on this website.