© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

The Imperial Japanese Navy

In little more than fifty years Japan has grown from small beginnings into a naval Power of major importance with a fleet which, in efficiency, as well as in numbers, rivals the navies of any part of the world

FLEETS OF THE FOREIGN POWERS -

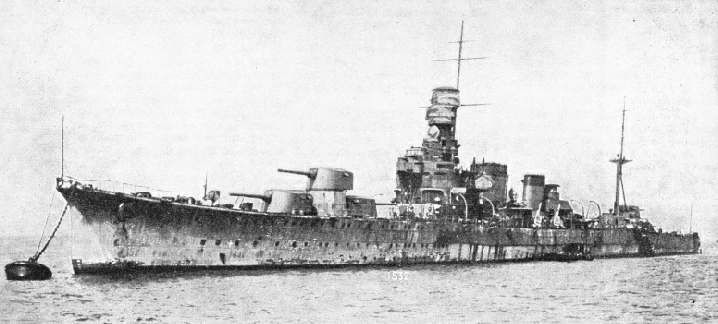

LAUNCHED AT BARROW, LANCASHIRE, IN 1913, the Kongo was the last important Japanese warship to be built abroad. Displacing 29,330 tons, the Kongo has an overall length of 704 feet, a beam of 92 feet and a draught of 27 ft. 6 in. This photograph shows the Kongo before her extensive alterations in 1926-

THE sudden transformation of Japan from an obscure kingdom existing in hermit-

There is no record of an organized navy having existed at that period, but in 1860 an armed wooden steamer was laid down at Nagasaki. This vessel was the first steamship to be built in the country.

During the following ten years a number of warships were bought from America and Europe. These vessels comprised the Imperial squadron which in 1869, during the civil war between the Imperialists and the supporters of the Shogun (dictator), fought an action with the Shogunate fleet at Hakodate and gained a victory. This war not only welded Japan into a united empire, but also gave her rulers their first lesson in the value of sea power — a lesson which they promptly turned to account.

Shipyards were established in many parts of the country, including a Government-

Ironclad construction, however, was still beyond the national resources, and for many years Japan continued to buy such vessels abroad, the earliest being a small battleship and two armoured corvettes ordered from British firms, in 1876. A few years later she acquired two cruisers, the Naniwa and the Takachiho, which were built in England on the Tyne, and were destined to make history in the Sino-

Meanwhile the young navy, recognizing the importance of the human factor in naval efficiency, applied to the British Government for the loan of officers to act as advisers and instructors. The first British officer to visit Japan in this capacity was Admiral Tracy, who was succeeded by Admiral Hopkins and then by Captain John Ingles.

Japanese historians warmly acknowledge the services performed by these British advisers. Count Okuma, one of Japan’s leading statesmen, wrote in his memoirs: “We are indebted to Western experts for the inception and subsequent development of our Navy; especially to the British Government for the courteous loan of a number of their capable officers to serve as instructors at the cadets’ college in Tokio. The men of deeds and ability that the Imperial Navy now possesses are the direct consequence of the tuition then granted us by British officers.”

The remarkable growth of Japanese sea power attracted little notice abroad until 1894, when a dispute over Korea led to war between China and Japan. During this campaign the Japanese fleet was handled with a skill that amazed foreign beholders. Steam tactics, gunnery and torpedo work were all carried out with a smartness and precision which would have done credit to any navy in the world. At the battle of the Yalu (September 17, 1894) a Japanese cruiser squadron utterly defeated a Chinese force which included two powerful battleships, sinking several vessels and driving the remainder into a fortified anchorage, where they were later attacked with the utmost gallantry by Japanese torpedo boats.

During the ten years following the successful war with China the Imperial Navy steadily increased in strength and efficiency. First-

In the Russo-

Japan’s resources had, however, been severely taxed by the titanic struggle with Russia, and for the time being she was not in a position to make any large addition to her naval armaments. It is true that her fleet was reinforced by a number of ex-

Problem of the Pacific

This increment in strength, however, proved to be but temporary, for the advent of the dreadnought type in 1906 had the effect of rendering obsolete all big warships of earlier design. Japan, in common with every other naval Power, was confronted with the gigantic task of rebuilding her battle fleet on a dreadnought basis.

For a nation whose treasury had been sadly depleted by the exactions of war this was a serious problem, and for this reason the development of the Japanese Navy in the ten years following the struggle with Russia was on a relatively much smaller scale than the progress which had been achieved in the previous decade. In the war of 1914-

part, though it co-

This qualification is important and needs to be briefly explained. Modern warships have a radius of action conditioned first by the quantity of fuel they can carry, and secondly by the base or dockyard facilities at their disposal. It follows, therefore, that a battleship or cruiser of to-

There are few non-

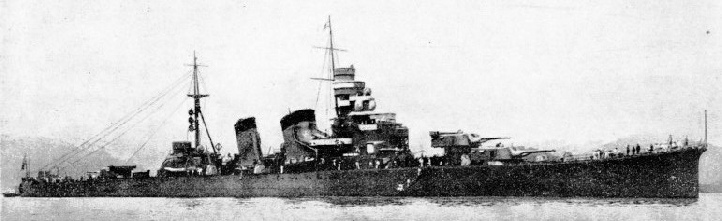

ARMED WITH SIX 8-

This lack of suitable local bases, coupled with the limited cruising radius of modern warships due to the handicaps mentioned above, would effectively prevent any foreign Power from concentrating the greater part of its naval strength in or near Japanese waters. On the other hand, Japan herself has a number of thoroughly modern and well-

These considerations were duly weighed by Japan when she drafted her new naval programme in 1916. It provided for the building and maintenance of eight battleships and eight battle cruisers of the most powerful type, as well as a proportionate number of cruisers, destroyers and submarines.

Behind the sixteen first-

The cost of this programme would have been enormous, but the Japanese nation did not shrink from paying the price of what it deemed to be the minimum standard of naval strength consistent with security. Many of the new ships would, if completed, have overshadowed in size and armament the largest men-

The only foreign ships that approached these mastodons were the four British battle cruisers which were begun in 1921, but never completed. They were to have displaced 48,000 tons and to have been armed with nine 16-

This colossal Japanese programme did not go unheeded in the United States, which in view of its position in the Philippine Islands and its extensive commercial interests in China, could not remain indifferent to the balance of power in the Far East. Soon, therefore, an American building programme of even larger dimensions than the Japanese was announced, and there began a period of unavowed but obvious rivalry between the naval shipyards of the two countries.

Powerful Battle Fleet

Such was the position when the Washington Naval Conference met in 1921. The outcome of this momentous gathering is well known. The greater part of the Japanese and American building programmes were scrapped, Japan agreeing to restrict her future fleet to sixty per cent of America’s tonnage, on condition that the United States founded no new naval bases in the Western Pacific and suspended all work on those already existing. The treaty embodying this agreement was to end on December 31, 1936, and therefore the future naval situation in the Pacific is obscure.

Although the Philippine Islands have recently been granted their independence by the United States, America still retains responsibility for the defence of the islands and this obligation is to continue for a further ten or twelve years. As the Philippines are 4,800 miles distant from Hawaii, the only first-

It is possible, therefore, that the American island of Guam may be converted into a big fleet station, as was contemplated in 1921 before the demilitarization agreement was reached with Japan. A fleet based on Guam would be only 1,500 miles from the Philippines, and therefore excellently placed to cover them from attack.

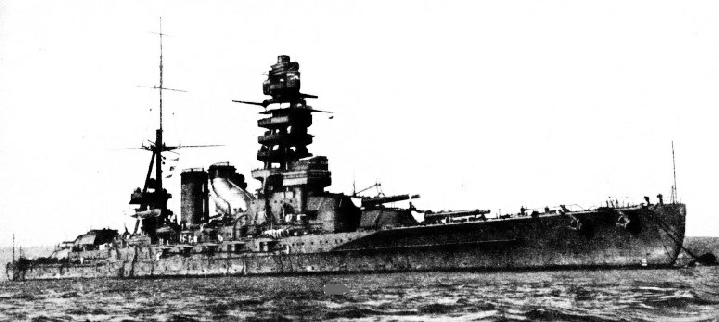

Under the Washington Treaty, Japan was restricted to a total of ten capital ships with a total tonnage of 301,320. This number was further reduced to nine by the London Treaty of 1930. To make the most of this small battle force each unit has been thoroughly modernized at great expense The two most powerful ships in the fleet of 1936 were the Nagato and the Mutsu, completed in 1920-

The Nagato and her sister present a somewhat grotesque appearance, as the forward funnel, having been bent back to keep the smoke away from the navigating bridge and the fire-

AN UNDULATING DECK LINE is not the least unusual feature of the cruiser Kinugasa, which was completed in 1927. Similar to the Kako (illustrated above) in dimensions, she has a speed of 33 knots. Her trunked funnels give her an almost grotesque appearance. Her armament includes six 8-

Next in order of age are the battleships Ise and Hyuga, completed in 1917-

Amidships there is a 12-

A feature common to all Japanese battleships is the enormous amount of tophamper they carry. Bridges and control stations seem to be indiscriminately piled one upon the other, the result being a towering pagoda-

Similar to ships of the Ise class are the Fuso and the Yamashiro, completed respectively in 1915 and 1917. Their displacement is 29,330 tons and their speed 22½ knots. The main armament is identical with that of the Ise, but the secondary battery comprises sixteen 6-

The last three units of the battle fleet of 1936 were the Kongo, Haruna and Kirishima, completed in 1913-

The Kongo, which was built in England in 1913, is noteworthy as being the last Japanese warship of any importance to be built abroad. Displacing 29,330 tons, the three ships originally had a uniform speed of 26 knots, though this has certainly been reduced by the fitting during reconstruction of extra armour protection and anti-

The Japanese battle fleet, therefore, is a small and somewhat mixed force, though its average speed is considerably higher than that of the American battle fleet.

Development of Naval Aviation

Always quick to accept new ideas, Japan has displayed characteristic enterprise in the development of naval aviation, in which respect she has set an example to older and more conservative navies. In 1936 she had seven aircraft carriers built and building, exclusive of two ships which accommodate seaplanes.

Further, all Japanese battleships and cruisers are lavishly equipped with aircraft, and Japan has created a chain of naval aerodromes ashore which extends the whole length of her coast-

The two largest Japanese aircraft carriers are the Kaga and the Akagi. The Kaga was laid down in the first instance as a battleship and the Akagi as a battle cruiser. Their speeds are 23 and 28½ knots respectively. Each has an armament of ten 8-

Other Japanese aircraft carriers are the Ryujo, of 7,100 tons and 25 knots, the Soryu and the Hiryu, of 10,050 tons and 30 knots, and the Hosho, 7,470 tons and 25 knots. According to official figures, the Japanese Navy in the summer of 1936 had over 400 ship-

Thirty-

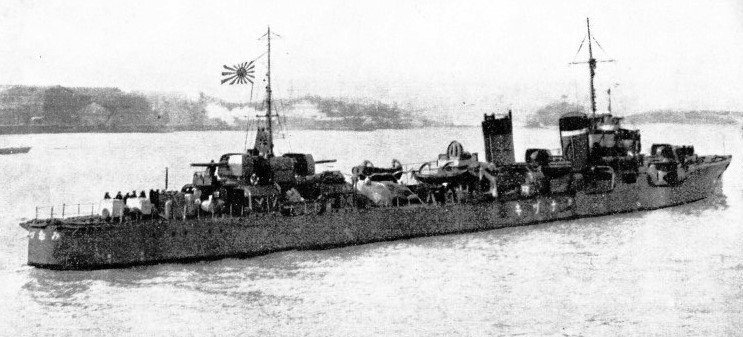

THE JAPANESE CHARACTERS painted on this destroyer are transcribed variously as Minadzuki or Minatsuki and signify the month of June. Built in 1927, the Minadzuki has a displacement of 1,315 tons. She has a length of 320 feet, a beam of 30 feet and a maximum draught of 9 ft. 10 in. The Minadzuki has a designed horse-

Each cruiser mounts a main armament of ten 8-

battle fleet, all these vessels are burdened with a tremendous amount of tophamper, and to foreigners at least, they look overloaded and unstable. It is an open question whether Japanese naval designers, in their ambition to cram the maximum quota of fighting power into a given displacement, have not in some instances overstepped the limits of safety.

In March 1934 a small torpedo boat of a new type, mounting an exceptionally heavy armament, turned turtle in rough weather and drowned most of her crew. Since this disaster the designs of other ships under construction have been modified, and in many instances deck weights have been drastically reduced.

A striking example of what appears to be “overcrowding” is afforded by the twenty-

Altogether Japan had 116 destroyers in 1936, the great majority being of modern construction. There were also eight new torpedo boats of less than 600 tons, mounting the relatively powerful armament of three 4.7-

Four of these vessels have an armament of two 5.5-

Next comes a large group of boats displacing about 1,640 tons, with the high surface speed of 19 knots and an armament which includes one 4.7-

Fortified Bases

The latest submarines have a surface speed of 20 knots. Having scrapped all her old boats, Japan now has a submarine fleet entirely of post-

An outstanding feature of the modern Japanese Navy is the symmetry and perfect balance which has been achieved by the pursuit of a wise building policy. The small but compact battle fleet is supported by an ample force of cruisers, heavy and light, and large numbers of destroyers, submarines, minelayers, minesweepers and depot ships, all working in co-

The fleet is manned by about 90,000 officers and men. Of the men the greater number are long-

Japanese naval officers rarely have interests outside their profession, and even their recreations are more often than not some form of military training. When afloat they lead Spartan lives, dispensing with most of the comforts enjoyed by the officers of Western navies. The cabins and ward-

The bluejackets, too, live the simple life in every sense of the word, but in spite of rations which would excite the derision of a British sailor, and microscopic rates of pay, the Japanese fleetmen are cheerful souls who do their work with marked efficiency.

Discipline is strict, though by no means harsh, the attitude of the average officer to his men being distinctly paternal.

Foreign observers familiar with the Japanese character are inclined to doubt whether the personnel of the navy has fully mastered the complexities of modern naval technique. Be that as it may, all the available evidence suggests that despite their relatively short history the Japanese can handle warships, great or small, no less competently than the seamen of other nations.

A JAPANESE BATTLESHIP of 32,720 tons displacement, the Nagato was laid down in 1917 and completed in 1920. Extensive rebuilding was carried out in 1934-

You can read more on ”The Battle of Tsushima”, “Japanese Shipping” and

“The United States Navy” this website.