© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

The United States Navy

The two most striking features of the modern United States Navy are the strength and power of the battleships and the number of destroyers and submarines

FLEETS OF THE FOREIGN POWERS -

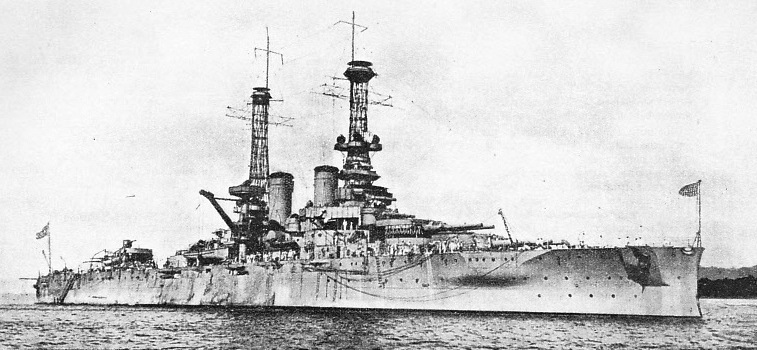

THE LATTICE MASTS, at one time such a distinctive feature of United States battleships, have been replaced by tripod masts, of the British type, in the more recent battleships. The Arkansas, built in 1910-

MANY people in Great Britain would be surprised to learn that the United States Navy has been in existence for over 160 years. Most of us are accustomed to regard the great English-

Although this new fighting force was called into being to wage war against Great Britain, it was closely modelled on the British Navy in its organization, customs and discipline, and of its original personnel probably ninety-

Several of its ships proved more than able to hold their own in action with veterans of the British fleet, and it is on the hard-

Yet the naval operations of these two wars were mere side-

It is the considered verdict of all historians that had the Federal Government owned a naval force of sufficient strength to establish from the outset even a moderately effective blockade of the Southern coast-

When the Civil War ended the United States Navy had become exceedingly formidable, alike in the number and quality of its ships and in the proficiency of its war-

The position, therefore, was that the United States could, had it wished, have developed from its existing resources a really powerful battle fleet, equal if not superior in quality to that of any afloat. But the country was weary of war and, instead of developing the improvised armaments at its disposal, it turned to the more congenial and eminently Anglo-

For the next twenty years the navy led a hand-

Not until 1883 was a beginning made with the building of steel ships, and several more years elapsed before the first genuine battleship, the Texas, was laid down from designs furnished by a British naval architect. From then onwards a fairly methodical shipbuilding policy was pursued. When the war with Spain broke out in 1898 the United States had a small but well-

The father of the modern American Navy was without doubt the late Theodore Roosevelt. During his term as President large shipbuilding programmes were undertaken.

It is unnecessary here to recapitulate the services performed by the United States Navy after April 1917, when America entered the war of 1914-

The Washington Conference

In the United States itself a colossal programme of shipbuilding was launched, including over 200 destroyers and though the war ended when but few of the new vessels were ready for action, the immediate post-

At this juncture, however, certain economic and political factors came into play, and eventually led to the summoning of the Washington Conference, from which emerged in 1922 the famous agreement for the limitation of naval armaments. By this compact the British Empire and the United States were placed on an equal footing in naval strength, and Japan, France and Italy were allotted lower ratios of fighting tonnage. So far as Great Britain and America are concerned, the principle of “parity” then established still holds good and, although the original agreement was due to lapse at the end of 1936 it is well understood that naval rivalry between the two countries is definitely and permanently eliminated.

In 1932, for the first time in American history, legislation was introduced which automatically effected the timely replacement of obsolete ships of the American Navy. A certain standard of strength is to be achieved by 1942, and thereafter maintained by such new construction as may be necessary to replace ships of every type as they approach the age limit. This far-

It is abundantly clear that the United States are firmly resolved to implement the policy of building and maintaining a navy “second to none”.

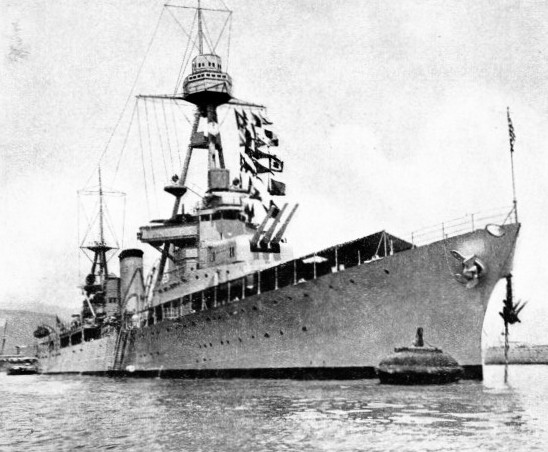

A LIGHT CRUISER of 7,050 tons displacement, the Detroit is one of the ten vessels of the Omaha type completed in 1923-

The United States Navy, of which the President is Commander-

In 1936 the United States Navy had a personnel, including Marines, of 17,000 officers and over 110,000 men, a figure well in excess of the British total. The material built and building included fifteen battleships, thirty-

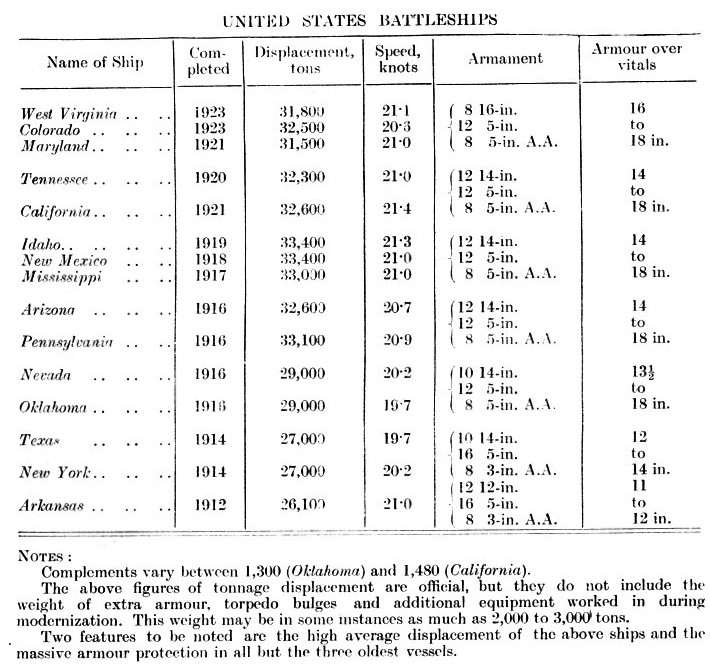

American ships are as a rule more heavily armed than British ships of corresponding size, a practice which has been consistently adhered to from the earliest days of the United States Navy. The principal details of the fifteen American battleships will be found in the table below.

In spite of the difference in the calibre of their main armament, the ships from the Colorado to the Arizona (in the table) are almost uniform in design, and therefore comprise the most homogeneous and possibly the most formidable group of battleships afloat. A feature that does not appear in the table is the extremely efficient system of underwater protection in the later ships.

What these vessels could stand in the way of punishment was indicated by experiments with a sister of the Colorado, the Washington, which had to be discarded by international treaty. This vessel remained afloat after a series of heavy explosive charges, corresponding to the most powerful torpedoes and air bombs, had been detonated against her hull below the water-

“All or Nothing” Principle

Nine of the U.S. battleships have triple mountings for their big guns, a system which the British Navy was slow to adopt but eventually incorporated in the Nelson and the Rodney. It has the advantage of saving weight and simplifying fire control and is likely to be adhered to in future construction.

Despite their age, the Oklahoma and the Nevada are two of the most interesting ships in the fleet, inaugurating as they did a new departure in battleship design. They were planned on the so-

All but three or four of the fifteen U.S. battleships have been thoroughly rebuilt and modernized in recent years at an average cost of £2,000,000 a ship. This process has included the provision of anti-

A HEAVY CRUISER with a displacement of 9,100 tons, the Salt Lake City is a sister ship to the Pensacola, illustrated below. Built in 1929, the Salt Lake City has a length of 570 feet between perpendiculars a beam of 65 ft. 3 in. and a mean draught of 17 ft. 5 in. Four sets of geared turbines housed in two engine-

The American Navy has been the pioneer in adapting air power to naval purposes and in furnishing ships with the most efficient means of defence against air attack. One interesting item of battleship modernization in America has been the fitting of tripod masts of British type in place of the ungainly lattice or cage structures which were for many years a conspicuous feature of United States capital ships. The cage mast was introduced in the belief that it could not be destroyed by shell fire, but experience proved it to be unsuitable for fire-

Thanks to the excellence of their original design and the completeness with which they have been modernized, the fifteen American ships constitute a battle force inferior to none in existence. On a purely technical comparison the British battle fleet may appear to possess an advantage by reason of the heavier calibre of its guns, but in fact the difference is slight, and fully compensated by the superior volume of fire which the American force, with its more numerous guns in each ship, is able to develop.

Until comparatively lately the building of cruisers had been neglected in America, so that the navy lacked balance. It became, as it were, an inverted pyramid, top-

Up to 1936 twenty-

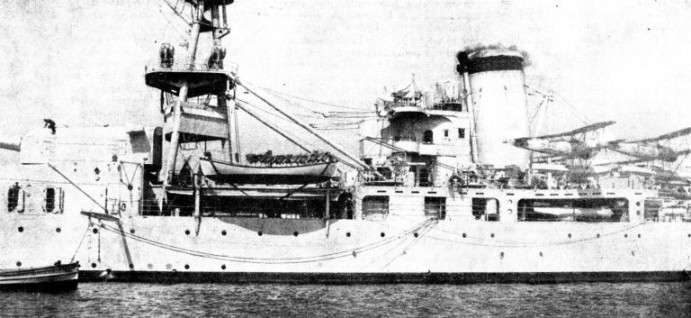

SEAPLANES CARRIED ON BOARD the United States cruiser Pensacola are housed between the two funnels. The Pensacola carries four seaplanes and is equipped with two catapults. Her armament includes ten 8-

Besides the twenty-

If the British Navy can claim the distinction of having built the first aircraft carrier, America has had her full share in the later development of this type of vessel. In the Lexington and the Saratoga she has two carriers which are unique in size, speed and aircraft capacity. Laid down in 1920 as battle cruisers, they were shortly afterwards redesigned as carriers, in which role they have proved most successful. Either ship displaces about 33,000 tons, and is propelled by turbo-

speed of nearly 34 knots. The full capacity of the Lexington is ninety aircraft and that of the Saratoga seventy-

The drawback of these magnificent ships is the enormous target they offer to every form of attack, not least to air bombardment. Moreover, each cost more than £9,000,000, a figure calculated to stagger the taxpayers of even the wealthiest country. For these reasons the two carriers of the Lexington type are never likely to be repeated. A new carrier, the Ranger, of 14.500 tons, with a speed of 29¼ knots and a capacity for seventy-

Even to-

Strategic Effect of Panama Canal

Between 1932 and 1936 seventy-

The American Navy has always been partial to submarines. The total completed and under construction during 1936 was 106. The majority of these, however, were old boats laid down during or immediately after the war. Among the newer boats are two of the largest in the world, the Nautilus and Narwhal, whose tonnage when submerged is 3,960. Their armament is two 6-

In modern times the development of' the American Navy has been largely influenced by the geographical factors which invariably determine national strategy. Before the opening of the Panama Canal, American warships in the Atlantic could reach the Pacific only by rounding Cape Horn, the voyage from New York to San Francisco involving a run of 13,300 miles. While these conditions prevailed the United States found it expedient to maintain separate fleets in the Atlantic and the Pacific, because in an emergency it would have been impossible to effect a concentration for several weeks.

This division of force made the United States Navy weak at all points, though it derived a certain security from the great ocean distances which separate North America from Europe on the one hand and from Asia on the other. The opening of the Panama Canal in 1914, however, completely altered and simplified the strategic picture. The sea route from New York to California was cut from 13,300 miles to 5,260, which meant that fast ships could be transferred from one ocean to the other at comparatively short notice.

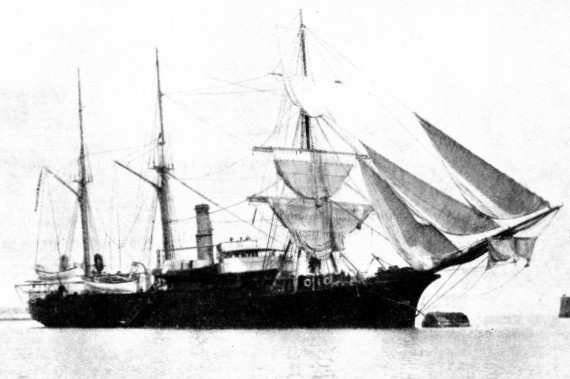

A STATE TRAINING SHIP built at Chester, Delaware County, Pa, in 1876, as the United States screw sloop Ranger. She was armed with one 11-

In these circumstances sound strategy dictated the formation of a single battle fleet to be stationed either in the Atlantic or the Pacific, and after some years of hesitation the American authorities decided to adopt this course. The Pacific was chosen as the normal cruising and practice ground for the newly constituted “United States Fleet”, which is now based on the Pacific coast, with its headquarters at San Francisco and subsidiary bases at San Diego (California), San Pedro (California), Bremerton (Washington) and Hawaii, 2,100 miles south-

From time to time the fleet visits the Atlantic for short periods, but that ocean is for the greater part of the year denuded of warships other than small local flotillas. Without unduly stressing the inferences suggested by this fact, it does seem to indicate that the United States does not regard the Atlantic as a potential danger zone, as it might become if the balance of naval power in Europe were upset by a sudden collapse of British naval strength.

Despite the increased mobility conferred upon it by the Panama Canal, the United States Navy, as with the British is essentially an oceanic force which has to visualize the possibility of waging a campaign in areas remote from its home bases. This serves to explain why American naval officers have always preferred their ships to be of large dimensions and endowed with the greatest possible radius of action. Ship for ship, American men-

The officers of the United States Navy arc thoroughly trained and exhibit marked professional keenness The American naval officer is trained in deck and in engineering duties.

The quality of the lower-

temperament, the navy has no difficulty in attracting a sufficient number of the best type of recruits.

The United States Marines form a corps as old as the navy itself. As with the British Royal Marines, they are “soldiers and sailors, too”, and although their principal duty is to provide garrisons for the naval bases and colonial dependencies, marine contingents serve on board most of the larger ships of the navy. Marines formed the vanguard of the American Expeditionary Force which came to France in 1917.

In recent years the United States Navy has intensified its training programme, and now spends as much time at sea as any other navy. Grand manoeuvres lasting several weeks are held every year, and during these periods every ship in commission is engaged in realistic war training. From all accounts, American naval gunnery stands at a high level, and marked progress is reported in torpedo and mining work. Thanks to its huge air force, the U.S. Navy has been able to develop the collaboration of ships with aircraft on a scale not yet approached by any foreign service.

To-

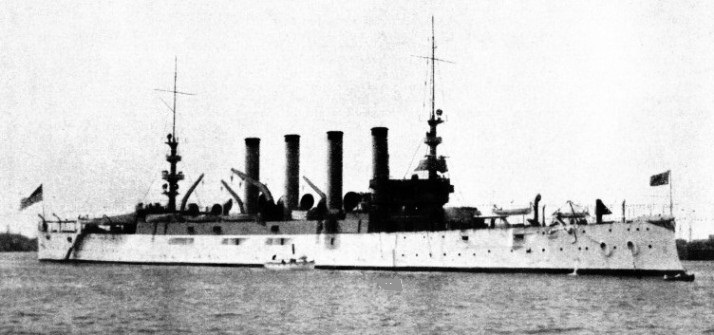

AN EARLY UNITED STATES ARMOURED CRUISER, the Maryland was laid down in 1901 and completed in 1906. The Maryland had a displacement of 13,680 tons a length of 502 feet, a beam of 69 ft. 6 in and a maximum draught of 26 ft. 6 in. Her normal complement was 878 or 921 as a flagship.

Click here to see the photogravure supplement to this chapter.

You can read more on “American Shipping”, “Floating Aerodromes”, and “Raising the Maine” on this website.