© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

American Shipping

The policy of Government subsidies for American shipping has been dictated by economic circumstances which have existed since the United States were first established. The work of the U.S. Shipping Board has made the The American Merchant Service the second largest in the world

SEA TRANSPORT OF THE NATIONS -

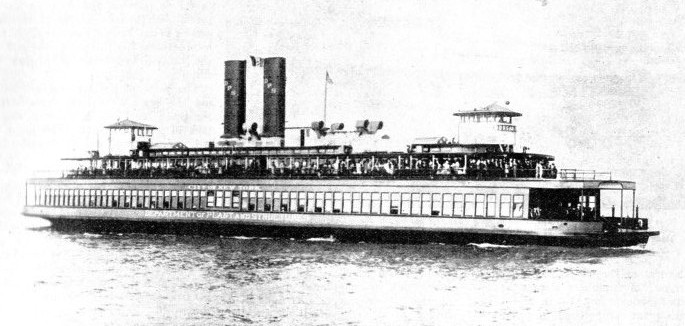

A NEW YORK FERRY STEAMER, the Dongan Hills, built in 1929, is typical of the numerous ferries which transport vehicles and passengers across the waters of New York Harbour. These vessels steam straight into the specially built ferry docks on either shore, and passengers as well as vehicles disembark from either end. To facilitate this manoeuvre the Dongan Hills, which is 267 feet long, has screws fore and aft.

THE American Mercantile Marine has made such rapid progress since 1914 that it is now the largest in the world with the exception of the British Merchant Service. The history of the growth of American shipping differs in many details from that of other maritime nations because, almost as soon as the United States had been established, a policy of protection for shipping was forced upon them by circumstances.

Although protection is the keynote of American shipping policy, it must be realized that the country was born during an era of the strictest commercial protection. The commercial development of the Colonies had been checked by the British Navigation Acts which were then in force, and the shipowners and shipbuilders had to fight their British and foreign competitors for every dollar’s worth of trade. The colonies’ commerce with the Spanish West Indian colonies, always one of their most important trades, had to be carried out in defiance of similar and even stricter laws passed by Spain. This trade continued without a check, but only by utilizing the fastest ships and running the risk of imprisonment.

The colonies had their trade restricted in this way for many years, and it is not surprising that they should have followed a similar course themselves as soon as they gained their independence. The Atlantic coastal trade was strictly reserved for ships flying the Stars and Stripes, and American registration was entirely barred to foreign-

In the earliest years of American shipping, expenses tended to be high, except in the construction of wooden sailing ships. After the Civil War expenses mounted higher still, for the opening up of the West offered such good opportunities of advancement to the youth of the country that few young men responded to the call of the sea as a profession. No sailor, for example, could hope for the wages and prospects offered on the land to any man of ordinary ability and ambition. This was one of the main causes of the decline of the American Merchant Service. In addition, their unlimited supplies of shipbuilding timber tempted them to continue building wooden ships when Britain was using iron.

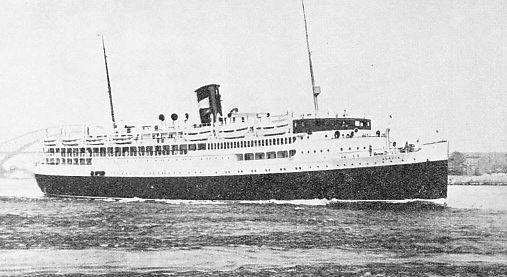

ON THE COASTWISE RUN between New York and Yarmouth, Nova Scotia, in the summer and between Boston and Yarmouth in the winter, the Eastern Steamship liner Acadia maintains a speed of 18 knots. She was built in 1932 and has a gross tonnage of 6,185. Her length is 387 ft. 5 in; her beam 61 ft. 3 in. and her depth 27 feet.

On the outbreak of war in 1914, therefore, American shipping was almost confined to those services which were protected from cheap foreign competition by the coastal reservation laws on the Great Lakes, on the Eastern and Western coasts and on the intercoastal run round Cape Horn, and later through the Panama Canal. The American big ships were confined to four liners on the Atlantic and a few on the Pacific. The American flag supported only fifteen foreign and five intercoastal services. The 112 American vessels, carried only ten per cent of the foreign trade.

The war in Europe caused a complete reversal of American shipping policy. The Americans saw that in a struggle of such great proportions a boom was inevitable and they prepared to make the most of it. As soon as the cheaper competition of European ships had been withdrawn, the Americans encouraged the other nations to transfer their ships to the United States for safety. The protective laws were nearly all relaxed either temporarily or permanently. Between 1914 and 1917, when America came into the war on the side of the Allies, not only were numerous ships transferred to American registry, but also all the established shipyards were working to capacity and numbers of new yards were established all round the coast. The new Merchant Service of the United States had been born.

The U.S. Shipping Board had been created as a Government department in 1916 to encourage the building of faster and better ships and to regulate the building of an adequate Merchant Service for peace and war. In this way the machinery was all ready to answer the Allies’ cry for more ships to replace the large number sunk by enemy submarines.

To accelerate production, standardization was adopted to a great extent. Sometimes fabrication was employed and nearly all the necessary work was done at a bridge or at a general engineering establishment well away from the water, and the parts were sent to the shipyards to be assembled. The necessity for speedy construction also influenced the choice of engines and boilers. The traditional wooden ships came to the fore again, and a large class of nearly 600 wooden vessels was built because wooden vessels could be completed more rapidly than steel ships. This class proved an utter failure, however, for the green timber which was used warped and caused leaks, often before the vessels were loaded.

Most of the ships built at this time were intended for bulk and special cargoes. They carried supplies of every kind to the Allies, and never attained a speed of more than 10½ knots. A few faster vessels were built, and others originally intended as transports were easily converted to passenger purposes. Altogether the Shipping Board built about 3,500 sea-

The work of putting to commercial use this mass of material, created by the State regardless of expense, was a task of great difficulty. The material was there, but all the other elaborate structure of a great industry had to be built up. The Shipping Board continued to exist, although as soon as circumstances permitted, the authorities had to face the delicate task of transferring its work to private ownership as gradually as possible.

The avowed purpose of the Board was to re-

In some instances the Government took all risks and bore all losses, but the companies always received their full shares of any profit that might be made. In other instances the ships were to be gradually transferred to the companies on hire-

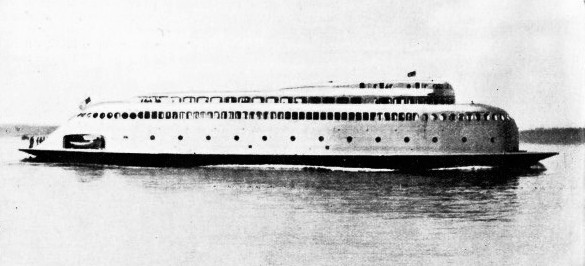

A STREAMLINED PASSENGER FERRY runs across Puget Sound in the State of Washington, U.S.A. The first completely streamlined ship in the world, the Kalakala, was converted in 1935 from a ferry boat of more orthodox design. Her enclosed decks offer the greatest comfort to the passengers. The Kalakala is 276 feet in length, with a beam of 55 ft. 8 in. and a draught of 13 feet.

The effort continued. In 1920, 42·7 per cent of America’s foreign trade was carried in American ships, and in the same year 584,000,000 dollars (then equivalent to about £180,000,000) of new private money were invested in shipping. American vessels were given preference whenever possible. The inefficient and too hastily built ships were laid up. The Shipping Board had sufficient means to carry out expensive experiments with turbo-

This Merchant Service, protected as it was by the State, had to face other nations in open competition for the world’s trade. There were many handicaps. The American ships had nearly all been hastily built in circumstances of war with standardization as the key policy. They were thus too much of a single type and their employment for special services reduced their efficiency. The majority were far slower than their foreign competitors and speed was becoming more and more important.

To allow the owners to build and maintain the tonnage that, suited their service best, the Jones-

This subsidy was nominally for the carriage of mail, but the payments were often ludicrously large. In at least one instance, £2,866 was paid for transporting a single small bag of mail between the United States and New Zealand. It was generally recognized that the subsidy was a “mail subsidy” only in name and that the main purpose of the Act was to provide necessary reserves, store ships and other requirements of the United States Navy.

The shipowners were not slow to take advantage of their opportunity and some fine ships were built. On the service between San Francisco and Sydney ships of 6,000 tons with a speed of 16½ knots were immediately replaced by the Mariposa and her sisters, of 18,000 tons and having a speed of 20½ knots. On the service between New York and Havana the best ships that the Ward Line had built from its own resources were the Orizaba and Siboney. Vessels of 6,940 tons gross, they had a speed of 17 knots and

accommodation for 430 passengers. When the Jones-

By far the greater part of the present American deep-

By far the greater part of the present American deep-

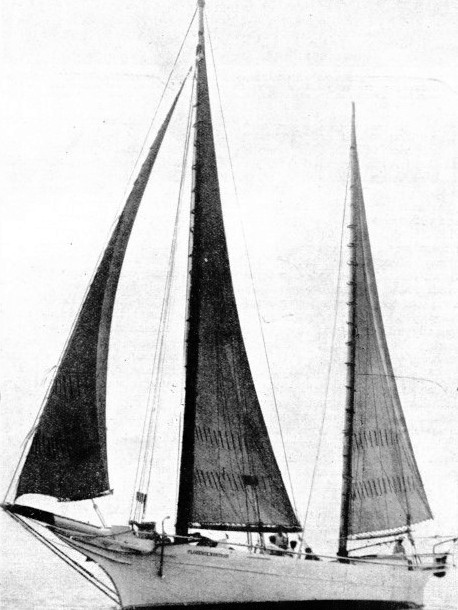

IN CONTRAST TO THE THAMES BARGE, the Florence Northam is an American sailing vessel of the class known as “bug-

The Dollar liners President Coolidge and President Hoover, 22,000 tons gross, with a speed of 21 knots, run between California and the Orient and belong to the class of independently designed vessels. On the Atlantic routes the cabin liners Manhattan and Washington also are included in this class. These liners, of 24,289 tons gross, have a speed of 22 knots, and are among the most popular on the Atlantic Ocean. In addition there are ex-

The most interesting technical work done with the assistance of the Jones-

Perhaps the most striking conversion was carried out by the Baltimore Mail Line. This company planned to run a subsidized passenger and cargo service across the Atlantic, maintaining a regular weekly schedule between Baltimore, Norfolk (Virginia), Havre, and Hamburg -

The most striking feature of the American overseas fleet, compared with its British counterpart, is the large number of cargo liners running on regular berth. The absence of tramps is also characteristic of American shipping. This may partly be attributed to the fact that the subsidies are paid only on regular services, and partly to the higher running costs of the American ships. Not only do they pay much higher wages, but their crews are also almost invariably larger than in similar ships under European flags. Any tramp cargoes that the Americans have to offer are nearly always for foreign ports. Thus they are not affected by the coastal protection, and a cheaper foreign ship may be employed, either for the voyage or on time charter.

Miniature Liners

The same applies to the tankers, whose cargoes of oil and spirit form an important section of American trade. Part of this is carried by water from the Californian oilfields through the Panama Canal to the Eastern States. This has to be done in American ships as it is a coastal voyage. Most of the tankers on this service are owned by the big oil interests and not by private companies.

For transport abroad a large amount of free tonnage from Europe is chartered for the voyage, although many of the most modern motor tankers that fly the Norwegian flag are really owned by the American oil companies which have financed their building and which have taken them on time charter for a number of years. The price they are willing to pay is ample to compensate the nominal Norwegian owners, and at the same time it saves the oil companies the cost of building their own vessels and running them under the Stars and Stripes. This policy, although commercially sound, is causing considerable uneasiness in American naval circles. Their fleet is almost entirely oil-

The tankers under the American flag are designed to run as economically as possible, and carry a large cargo at a moderate speed. Japanese owners, on the other hand, with the assistance of their Government, are building tankers with speeds as great as 19 knots.

The expense of keeping such ships at sea in ballast is offset partly by the fact that return cargoes of silk are carried and partly by the use of modern machinery. American owners are not inclined to follow suit unless the Government will pay them a special subsidy for so doing.

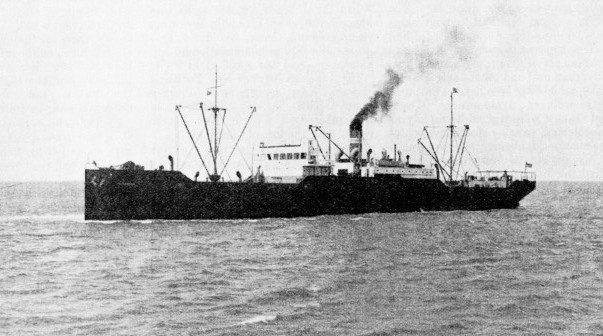

AN AMERICAN CARGO STEAMSHIP of the standardized type laid down by the United States Shipping Board, the Sundance was built in 1919. She has a gross tonnage of 5,183, a deadweight capacity of 7,775 tons, and a speed of 10½ knots. She has no features which are unnecessarily decorative. The hances (the rise and fall at either end of the well decks) come down at an angle instead of in the more usual graceful curve.

A striking American type is the miniature liner on the protected coastal trades. Despite the wonderful network of railways all over the United States the coastal services still run an excellent service for passengers and special cargo. Among the finest of these miniature liners are those built, generally with State assistance, for such companies as the Eastern Steamship Lines which serve the New England coast. The Clyde Steamship Company, too, has ships of this type up to nearly 6,000 tons, with a speed of 15 knots. The Southern Pacific Line, on its service between New York and the Gulf of Mexico, employs such fine coasters as the Dixie, a ship of 8,188 tons gross, with a speed of 15 knots and luxurious accommodation for 279 first-

Other types that are characteristically American are the passenger and freight steamers on the Great Lakes. These types are fully dealt with in the chapter beginning on page 519. The Greater Buffalo and Greater Detroit are, at the time of writing, the world’s biggest paddle steamers. This method of propulsion is employed partly to assist in the negotiation of ports that have little depth of water, and partly because the stability afforded by the paddle boxes sponsoned out from the sides permits extra passenger decks to be built. These ships, owned by the Detroit and Cleveland Navigation Company, have each a gross tonnage of 7,739 and a speed of 19 knots. The Great Lakes Transit Corporation and similar companies have 15-

The Great Lakes bulk freighters are even more peculiar. They carry a huge deadweight which has to be loaded and unloaded as quickly as possible, for the length of the ice-

Distinctive Ferries

Some of the American waterways, notably the Hudson River, also have some remarkable ships designed to carry the largest possible number of passengers on a light draught. Such ships as the De Witt Clinton, for instance, are paddle-

The large stretches of protected water in various parts of the United States encourage the building of what is generally known as the Sound type of steamer. These vessels carry towering passenger decks, and there are some large ships of this type that attain a high speed. The width of many American rivers prevents bridge construction, and trains and passengers have to be carried across stream by ferries. There are a large number of these ferries, ranging from the innumerable steamers that work in New York, to the Contra Costa, a huge wooden paddler of 5,373 tons. This ship was built in 1914 to carry Southern Pacific trains across San Francisco Bay. The numerous Pere Marquette ferries on the Great Lakes carry trains and also act as icebreakers.

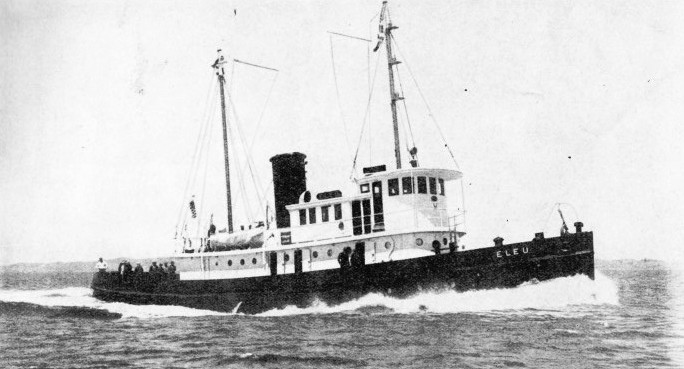

Such types as these are purely American and are not to be seen under the British flag. Similarly, the American tug is totally different from the British, and is designed to suit local requirements. The American tug does not tow from amidships with the whole of her after deck clear. Her hook is well aft, and she is always given a long deckhouse.

The American sailing ships that once were the “Queens of the Sea” have almost disappeared. There are a few coastal schooners remaining, and their design has been developed to extreme degrees in the desire to save running costs.

Worthy of special mention are the school ships maintained by the various States with the practical help of the United States Navy, for training boys for the sea. Formerly these were mostly old-

A TYPICAL AMERICAN TUG differs entirely in design from a British tug. The superstructures of British tugs are made as small as possible and towing hooks are placed amidships. The Eleu, shown in this illustration, has a long superstructure and her towing hook is placed well aft. A vessel of 335 tons gross, the Eleu has a length of 116 ft. 6 in. and a beam of 28 feet, with a depth of 14 ft. 4 in.

You can read more on “The Biggest Sailing Ship of her Time”, “The Manhattan and the Washington” and “The United States Navy” on this website.