© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

British Shipping

On all the seas of the world will be found vessels of different types flying the Red Ensign. It is the symbol of the greatest Merchant Service ever known and a flag that unites with a common bond seamen of many races

SEA TRANSPORT OF THE NATIONS -

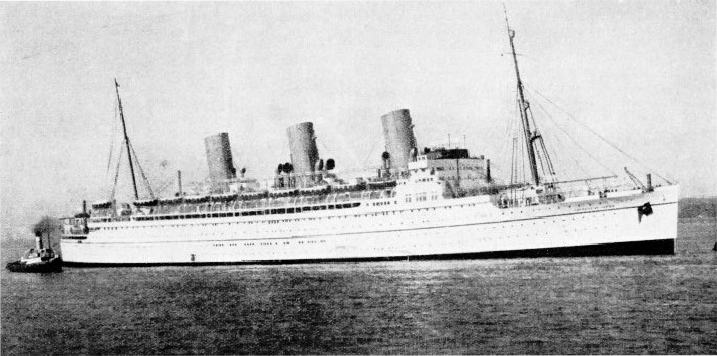

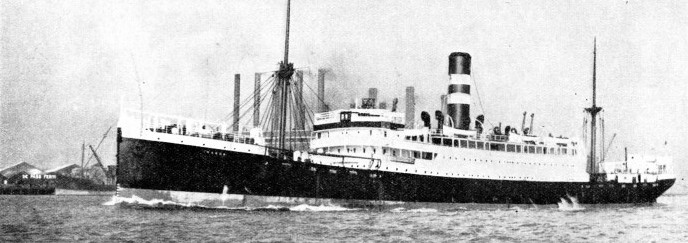

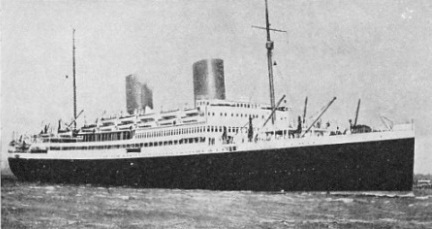

THE FAR EASTERN SERVICE from Vancouver is run by the Canadian Pacific Line with its luxury liners of the Empress class. Typical of these great ships is the Empress of Japan, which was built in 1930 and has a gross tonnage of 26,032. This vessel attains a speed of 21 knots.

SEAMEN may call the Red Ensign “Old Blood and Guts” in the same way as Americans call the Stars and Stripes “Old Glory”. When British sailors are disgruntled by cold and wet they may say that it is the worst flag under which a man can sail, but deep in their hearts they know that the Red Ensign of the British Merchant Service is a wonderful and beloved symbol. It links together men of all types, grades and races with an enduring bond that is revealed only in exceptional circumstances. The Red Ensign unites this heterogeneous collection of seamen and links all the material of the British Merchant Service, which is of greater diversity than any other in the world.

This service is still the biggest Merchant Service, and the Red Ensign is worn by most types of ship in some corner of the Empire or other. There are many types that have not been specially developed under this flag as they have been under foreign flags. There are also a few local types which have no counterpart in the British Empire. In general terms, however, the British Merchant Service is a complete catalogue of every type covered by modern maritime architecture, and every single type has its interest.

At the head of the list, a fine figurehead for the whole fleet, is the great express liner, the Queen Mary. The commercial importance of such liners is surprisingly small compared with that of other less imposing types of ship. In these liners the passenger accommodation, machinery and bunkers occupy all the available space, and the holds are limited almost exclusively to mails, passengers’ luggage and a few special items of cargo. Ships of this type can exist only on the main route across the Atlantic Ocean, and even there only in small numbers.

FOR SHORT-

On every other route in the world, the fastest passenger liners must have capacity for cargo as well, or they could not be kept on service. The term “passenger liner” covers a wide field. Apart from the giants, there are ships up to 30,000 tons gross on the North Atlantic, where the lower limit is now about 13,000 tons. Ships employed on the first-

A BRITISH COASTAL MOTOR SHIP of 1,120 tons gross, the Pacific Coast runs regularly between Liverpool and London for Coast Lines Ltd. Primarily designed to carry a general cargo, she also has accommodation for twelve passengers. The Pacific Coast was built in 1935, and her oil engines have sufficient power to maintain her designed speed of 12 knots in almost any weather conditions.

In all these vessels the architects have to compromise over the conflicting claims of passengers and cargo. The passenger accommodation must not be cut down too much, nor the deck space obstructed, yet hatches must be big enough for the quick loading and discharging of cargo. Some fine ships have failed on service because their hatches, limited for the convenience of passengers, have been so small that a full cargo could not be handled during normal stay in port. There must be complete cargo-

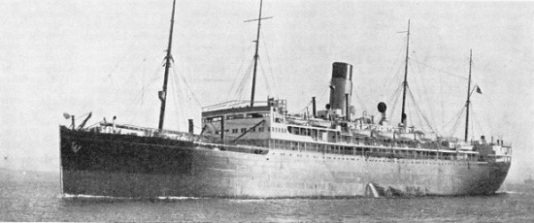

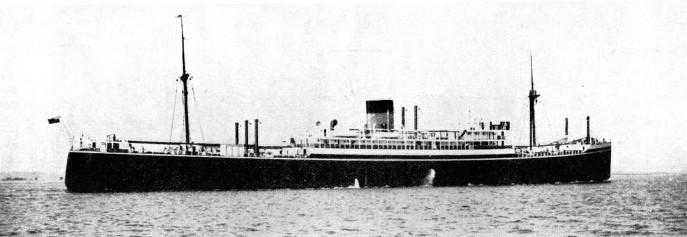

BETWEEN GREAT BRITAIN AND RANGOON, the Bibby liner Staffordshire is able to maintain a steady 15 knots. Although she was built in 1929, she is one of the few ships to retain the old rig of four masts and one funnel. The Staffordshire is a diesel-

There are many widely differing classes of passenger liner, designed according to the route the ship is to take and the class of trade in the service. Specialization has been carried to such an extent that surplus liners often go to the scrappers when only a few years old, whereas formerly a buyer, generally foreign, could always be found to adapt them for another trade. It is obvious that a ship designed to cross the North Atlantic in winter and summer demands different treatment from that given to ships that voyage in warmer climates. Her draught would make her useless for a service to ports with little depth of water.

Every trade has its own special task and every type of passenger has individual tastes. The lay-

Instead of three classes and sometimes steerage class in addition, most large liners carry only first class and “tourist third” -

Popular Cabin Class

It is now often difficult to distinguish the passenger liner from the cargo liner. Promenade decks are not infallible indications, since some of the latest cargo liners have abolished the old forecastle, with its unnecessary discomforts, and house the crew in two-

It is impossible in this chapter to deal in detail with the internal design of a passenger liner; the arrangement of public rooms to obtain the most striking effect; the ingenuity necessary to work attractive spaces round the funnel uptakes; the provision of space for children to play without disturbing their elders; the changes demanded by. the universal smoking habit of to-

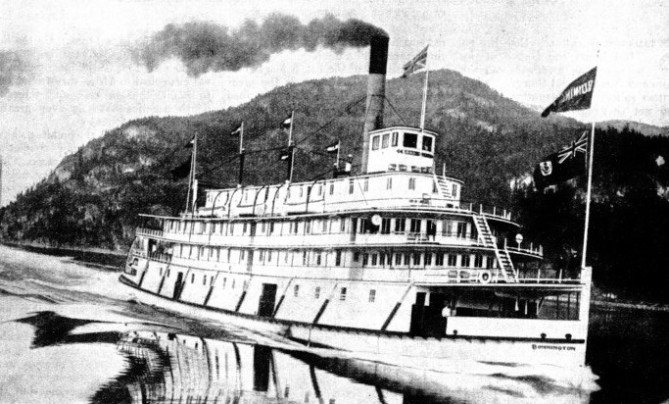

A STERN-

On the transatlantic services the number of ships with first-

In 1919 the designs were improved. The new ships had a gross tonnage of 16,500 and a speed of sixteen knots. In 1925 vessels of the Duchess type, of more than 20,000 tons, were built; they attained a speed of seventeen knots.

The largest British cabin ships until the Queen Mary was built were the 27,000-

The West Indian trade was once so large that the Royal Mail Steam Packet was the biggest shipping company of its day, but now this trade needs comparatively small ships. This is partly due to the present volume of the trade, and partly to the limitations of the ports that have to be used. The passenger business is made up largely of health seekers, and the ships have to be arranged accordingly. Many of the refrigerated ships engaged in the fruit trade from the West Indies have accommodation also for a number of passengers.

The mail ships to South Africa range up to about 25,000 tons gross in size. They run direct from Southampton, but the smaller Union Castle liners from London make many calls on the east coast, and some on the south-

Loading Cargo from Surf-

The size of ships engaged in this trade is gradually increasing because of the demand for faster speeds and the carriage of cargoes that require special treatment. Dutch and German competition is also a stimulant for this service. In addition to these routes to the African coast, the British India line runs a passenger service from Rangoon to East Africa.

Bullard, King & Co, a firm associated with the Union Castle line, finds many passengers who prefer its smaller ships, and a certain number of people travel to Africa in cargo liners. West Africa has conditions entirely its own, demanding special ships, and the Elder Dempster liners supply the greater part of this need. The features of these vessels are determined by many circumstances. They must be able to take cargo on board from lighters and surf-

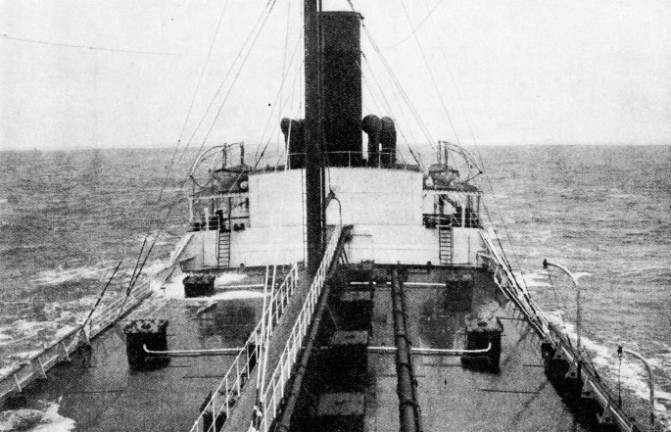

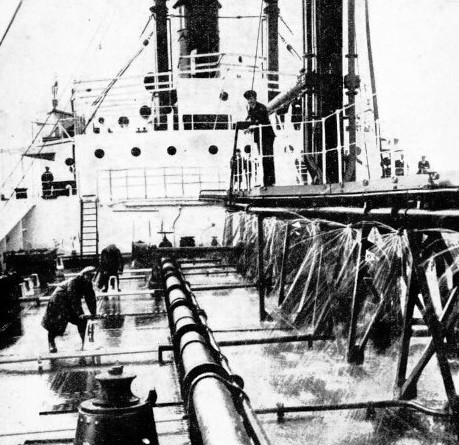

THE DECK OF AN OIL TANKER is comparatively close to the water, but the small tank hatches are hermetically sealed and there is no danger to cargo or to ship as long as the fore-

There is also keen competition on the route to South America from the Continent. The passenger trade on this route fluctuates considerably. In times of prosperity the South American is a great traveller to Europe, and he demands light, brightness and luxury on a lavish scale. Ships up to 22,000 tons from Southampton and of about 14,000 tons from London cater for this trade, under the Royal Mail and Blue Star Flags. The Pacific Steam Navigation ships from Liverpool still serve the west coast of South America, as they have done for nearly a century.

A South American liner would not suit the traveller to and from India, who regards his ship as a comfortable club and continues in it the social life he leads ashore. The P. and O. Company is predominant in the Indian trade and carries the Bombay mails, but there is a good deal of business for the secondary passenger services maintained by the Anchor Line and the Ellerman group. The British India line runs sundry services on the Indian coast and also from England to India. The Burmese trade is covered by the Bibby Line -

The Indian service of the P. and O. was once distinct from the Australian service. Modern machinery has so much accelerated the speed of liners that now these two services have been combined and the Australian ships call at Bombay. This necessitates a careful blending of the requirements and tastes of two types of passenger. The young Australian prefers much of the brightness demanded by the South American, although his taste differs in other ways. The improvement of the Suez Canal has enabled the Australian trade to be served by much larger vessels than formerly. Examples are the P. and O. liner Strathmore (23,428 tons) and the Orient liner Orion (23,371 tons).

The New Zealander wants nothing that is not typically British. The biggest, passenger ships on this service are motor ships of about 16,700 tons gross.

A PASSENGER AND FREIGHT LINER of 5,985 tons gross, the Harrison liner Inanda is engaged in the West Indian trade. This vessel was built in 1925 and registered at Liverpool. Her overall length is 407 feet and her beam 52 feet. She was originally built for a service to Natal, and was thus given the Zulu name Inanda.

Subsidized Competition

Ships of similar size serve the Far Eastern passenger trade, but they are steam instead of diesel-

Special Board of Trade passenger licences, with many precautionary restrictions and extra expenses, are necessary if more than twelve passengers are to be carried. Enterprising modern owners generally fit excellent accommodation into cargo liners for twelve passengers or fewer. There is always the chance that such ships may pick up passenger business when they are running to places that the normal passenger liners neglect. They are also much favoured by travellers with business connexions along their route; for in a passenger ship travellers must either curtail their interviews at each port to be ready for the ship to sail again, or else wait for the next ship and spend unnecessary time in port. The cargo liner requires at least a few hours in which to handle her freight; this gives the traveller ample time in which to conduct his business.

A STANDARD MODERN MOTOR TRAMP SHIP, the Sutherland is propelled by an opposed-

Cargo vessels are divided into two classes: liners which run on regular berth whether full or empty, collecting their general cargo from numerous shippers, and tramps which are chartered by one party at a time for single cargoes. The distinction, therefore, lies in the work rather than in the design. There is no reason why a ship should not be on regular berth one voyage and tramping the next. Innumerable cargo liners, when they are outclassed, are sold to become tramps under a foreign flag. Generally the regular trader is the faster, bigger and better vessel, and the necessity for reasonable access to any section of her cargo demands features not always necessary in a tramp.

The modern tendency of many trades is towards cargo liners and away from tramps, and this tendency is noticeable in every sea. A quicker turnover is permitted if the cargo is constantly received in small consignments.

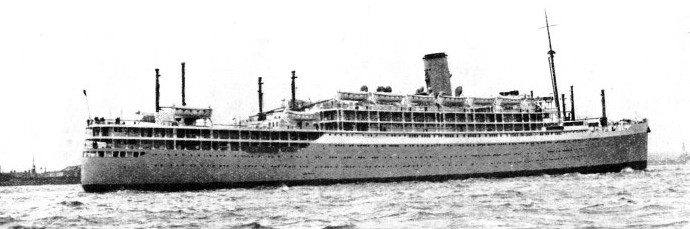

COMPLETED IN 1935, the Orient liner Orion, 23,371 tons gross, is one of the latest vessels in the Australian mail and passenger service. Her mainmast was eliminated to give her a modern appearance. She has two swimming baths on her deck. Her length between perpendiculars is 630 feet, her beam 82 feet and her depth 47 ft. 6 in.

Decline of “The Tramp Trade”

The number of British tramp steamers, once always referred to as the “backbone of the Merchant Service”, has declined rapidly, and cargo liners of greater speed and capacity have been built.

Speed is increasingly demanded for ships of this type, and engineers have made great improvements in the reliability and economy of the machinery. Careful hull construction has also become necessary, for the time-

Many cargo liners are specially designed for the particular work of their owners and are ill adapted for anything else. Meat cargoes, either frozen hard or chilled to the right temperature, demand elaborate refrigerating plant and the careful insulation of the bulkheads and decks. Dairy produce, but not fruit cargoes, can be conveniently carried in a meat ship. Although some meat ships have been diverted to the fruit trade, the modern fruiter is of a highly specialized design, with moderate size and high speed. Nowadays Great Britain alone builds new tramps in any number. Almost all her competitors buy them secondhand and run them as economically as possible to supply the cheapest form of transport. These tramps have to be designed to enter any port and to handle cargo there. These factors principally influence the draught of water and the design of the derricks.

A REFRIGERATED SHIP for the New Zealand meat trade, the motor vessel Waiwera was built in 1934 for Shaw, Savill and Albion. She is propelled by diesel engines which give her a sea speed of 16 knots. Her gross tonnage is 10,782, and she has a length of 516 feet and a beam of 70 feet.

The design of ocean tramps is an ingenious compromise, for the greatest carrying capacity seems to demand bluff lines, but the most economical propulsion demands fair lines. Happily, modern hull forms have greatly reduced the horse-

Low running costs are an important factor to the tramp shipowner, and it is surprising that the diesel engine, with its admitted economy in fuel and space, has not found greater favour. This is largely because an outward cargo of coal is still the mainstay of the business, and there is also the question of economy in running and first cost. A few tramps, mostly Scandinavian, have been equipped with diesel engines, but only recently has the experiment been tried on any large scale in Great Britain.

Cargoes of Silk or Oil

When the overseas petroleum trade grew up in the ’seventies the spirit was carried in barrels. Several attempts to evolve a tank ship to carry it in bulk had failed, but in the ’eighties the bulk oil tanker came into existence. Great Britain was the pioneer, but she has had to surrender a large part of the trade to Norway.

Tanker design is now almost standardized, with the machinery as far aft as possible to reduce the risk of fire and to simplify pumping arrangements. The bridge, with officers’ accommodation, is forward of amidships, and in some vessels a forecastle is connected with the bridge and after-

Inside the ship the hull is subdivided into numerous tanks with carefully built bulkheads. The tanks are connected with the elaborate piping installation and its attendant pumps. Provision is made to allow the cargo to expand in hot weather, at the same time avoiding a big surface of oil which would roll heavily at sea. Small air-

OIL ON TROUBLED WATERS. This excellent example of the work of Frank Mason R.I., the famous marine painter, shows a typical oil tanker battling with heavy seas. There are many varieties of tanker, but they all retain certain characteristics. They are relatively long, with the machinery space aft. Built for the carriage of crude oil and its derivatives in bulk, they are divided longitudinally and transversely into tanks. An expansion space is provided to allow for any alteration in the volume of oil in different temperatures. Normally, tankers carry no outward cargo, but occasionally they take fresh water to oil-

With cargoes of heavy oil, a tanker’s life can be as long as that of any other ship, but with a cargo of motor spirit, corrosion of the tanks is rapid, especially round the rivet heads and pumping connexions. Re-

By the nature of their work, tankers are given considerable length in proportion to their beam. This necessitates tremendous longitudinal strength to prevent their breaking in two amidships, and tankers are almost all constructed on the longitudinal system of framing. Economical running is a difficult matter, because a satisfactory way of carrying an outward cargo has not yet been found, so that the one journey with cargo has to pay the expenses of running both ways. Some Japanese tankers, however, carry cargoes of silk one way and oil the other way. Some oil-

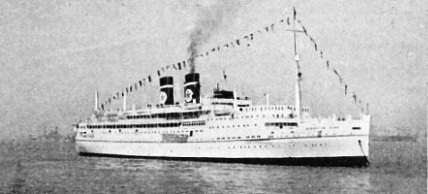

THE ARANDORA STAR formerly used on the South American passenger service, was converted by the Blue Star Line into a cruising liner with increased passenger accommodation. She was built at Birkenhead in 1927 and has a gross tonnage of 15,305. Her length is 512 ft 9 in, her beam 68 ft 4 in and her depth 42 ft 6 in. Her twin screws are driven by four steam turbines with single reduction gear fitted between the main engines and the screw shafting.

In addition to the ocean-

A PIONEER PASSENGER MOTOR SHIP, the Royal Mail liner Asturias, 22,048 tons gross, was built in 1925. Her diesel engines were replaced by geared turbine propulsion to increase her speed. Her length is 640 ft 6 in, her beam 78 ft 6 in and her depth 40 ft 6 in. She has twin screws driven by six steam turbines with single reduction gear. Fitted with refrigerating machinery, she has thirteen insulated cargo spaces, with a total capacity of 210,610 cubic feet.

Mail packets are exceedingly difficult to design for they generally run across troubled waters where seaworthiness is a first consideration. In most of them the draught of water is restricted by one or other of the terminal ports and, unless it is carefully designed, the shallow ship has an uncomfortable motion. The owners also require reasonable economy in circumstances that make it difficult to secure, for these ships spend considerable spells in port between short voyages at high speeds.

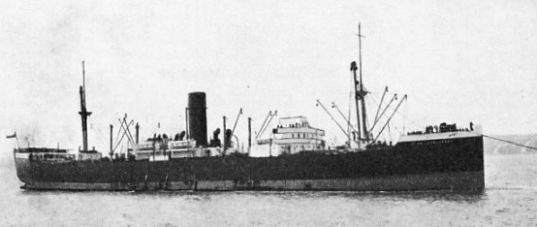

A CARGO LINER of 7,951 tons gross, the Clan Robertson was built at Glasgow in 1920. She has many derricks to facilitate the quick handling of cargo in port, and the two heavy-

Allied to the packets, but not so exacting in design because of lower speeds, are the vessels that maintain numerous services all round the British coast. In spite of growing competition from the roads, these little ships still attract large numbers of passengers as well as considerable parcels cargo. Their type is exclusively British and the passenger ships are all steam-

Early British Enterprise

Some colliers have collapsible funnels and bridge-

In addition to the coasters on regular routes there are also coastal tramps, available for full charter in the same way as tramps on overseas trades. Formerly these vessels were invariably steam-

Recently, however, the motor coaster has for many reasons proved far more useful than the average steamer. Motor-

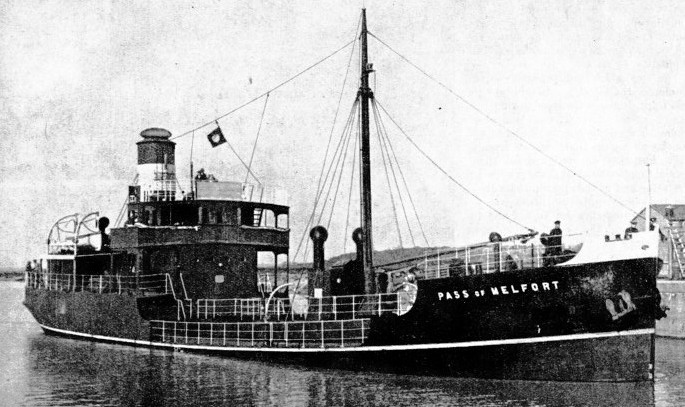

THE BRITISH COASTAL TANKER, Pass of Melfort, 757 tons gross, distributes to ports round the coast the motor spirit which is discharged by the overseas tankers at the main depots. Although this type of tanker is comparatively small, with a length of 182 feet and a beam of 30 feet, every precaution must be taken to protect the dangerous cargo. The spark-

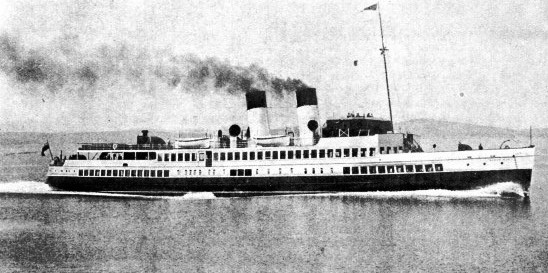

On the coast there are also excursion passenger vessels. This type varies widely according to the demands of the district. The Clyde has an excellent fleet of passenger ships, turbine and paddle-

The fishing fleet is as important to the country as the cargo ships. From the beginning of history Britain has been a fishing country. With the introduction of modern methods, much that is picturesque has been eliminated. The little inshore fishing boats have almost disappeared and there are few survivors of the huge fleets of sailing smacks. The British were the pioneers of fishing with power vessels, and still possess the finest steam-

The tug is the indispensable handmaiden of the big ship. In addition to this work, tugs are used for towing the barges on the River Thames and elsewhere. Tugs flying the Red Ensign may not be as big as many under foreign flags, but they are designed for their special functions and fulfil them well. In the latter half of the nineteenth century the tug’s most important task was to tow the sailing ship out to sea and to bring her in at the end of her voyage. Sailing ships have all but disappeared, but the size of steamers demands the help of tugs in and out of dock and on many other occasions.

A few paddle tugs survive, mainly on the narrow waterways, but the screw-

THIS CLYDE EXCURSION STEAMER was named the Queen Mary when she was built in 1933. Before the giant liner of that name was christened, this turbine steamer had to be renamed Queen Mary II, to comply with the provisions of the Merchant Shipping Act. She has a gross tonnage of 870 and a speed of 21 knots.

Allied to the tug is the salvage vessel, but nearly every tug is equipped with fire-

Among the numerous minor types of interest are the train ferries that carry passenger and goods trains overseas.

One of the latest additions to the Southern Railway Co.’s fleet is the Twickenham Ferry, designed as a train and motor car ferry for the service between Dover and the northern coast of France A twin-

SPRINKLING THE DECKS of the oil tanker Cheyenne with cold water as a precaution against the action of hot weather on her cargo of motor spirit. If this cargo were subjected to prolonged heat, there would be great danger of explosion. The Cheyenne, 8,825 tons gross was built in 1930 and has a length of 477 feet.

There are also specially designed motor-

Although the Mersey ferries are not now so widely used as they were before the Mersey Tunnel was opened between Birkenhead and Liverpool, the remarkably efficient vehicular traffic ferries still run regularly. These vessels are almost rectangular in shape to give the largest possible deck space for the miscellaneous cargo of motor-

In every corner of the British Empire there are special types of vessels designed to suit various local conditions.

You can read more on “Merchant Ship Types”, “Sea Transport of the Nations” and

“The World’s Largest Ships” on this website.