© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Modern Tramp Design

In recent years the introduction of the cargo liner has dealt a heavy blow at tramp shipping, which was regarded as the backbone of the British Merchant Service. Technical improvements, however, promise partly to restore the tramp’s lost position in a rapidly changing shipping world

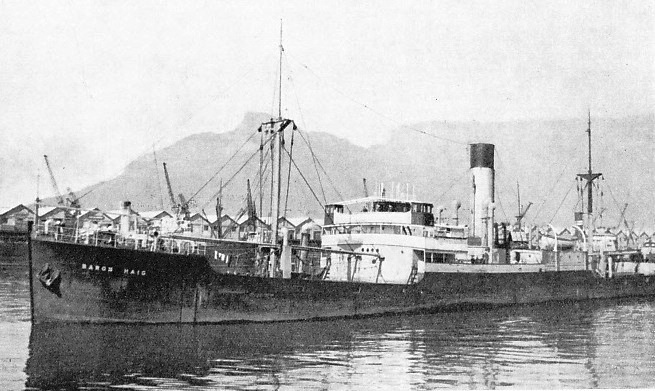

OUTWARD-

THE old-

The demands of shippers are more exacting than they have ever been before and trade conditions more difficult. The life of such a ship under the British flag is approximately twenty years, and to look ahead for that period, considering the changes that have come about in the last two decades, is in itself a great problem. Guess work is tempting but risky ; if an owner is going to lay down between £8 and £10 a gross ton he must base the design of his ship on the most careful calculations possible.

The essence of tramp operation is that the ship must undertake to go into any reasonable port in the world, and many of these are in poor shape. There fore, no matter how pressing other considerations may be, it is always necessary to keep the draught of water light. Special features which would improve her on one route, and would certainly be embodied in a liner, would probably handicap the tramp on another route and are strictly debarred in favour of general features which will enable her to do reasonably well on the maximum number of routes. As the new ship, with her high cost, will have to compete with cheaply-

Every era brings its own problems, but at the present time the greatest is probably how to combat the cargo liner’s tendency to encroach on the field of the tramp, how to offer shippers and consignees as many of the liner’s advantages as possible without sacrificing any of her own. The wheel will doubtless turn in time, and. the tramp’s advantage of cheapness will be appreciated, but the modern tendency is for merchants to secure a quick turnover of their money by getting the smaller consignments delivered by the liners at frequent intervals. The essence of tramp shipping is that the ships deal only with full cargoes, which take some time to collect and to dispose of and which incur warehousing charges during either operation.

With modern conditions it is not surprising that the business of the tramp has diminished. The type which was regarded as the very backbone of the British Merchant Service, and the most valuable of all in wartime, has been greatly reduced in numbers since the beginning of the great slump in 1921. It is unlikely that tramp tonnage will ever be rebuilt to its old strength. The cargo liner has certainly come to stay, and for years to come the difficulty will be to keep the tramp type alive at all.

The authorities fully appreciate the danger, and when British policy was finally changed, and a measure of State aid given to shipping, it was the tramp side of the industry which received attention. By means of the loan scheme, which helped in new construction, provided two tons were scrapped for every one built, measures were taken to secure the building of new tramps of the latest type.

The most conspicuous post-

British shipping has to meet foreign competition in various forms, but it is rather striking that the most dangerous rivals, and the ones which run their ships best, have a tendency to disregard tramps altogether because they cannot afford to maintain them under their regulations. On the other hand, the poorer merchant services, which can offer transport at the lowest prices because

of their poor standards, generally concentrate on tramps and have no liners at all.

Every British ship, tramp or liner, is run according to a scale of manning, victualling and the like that has been agreed upon between the owners and the men, but many foreign rivals have no such scales and many others, although they publish their agreed schedules, make no effort to keep to them.

Importance of Fuel Costs

Numerous instances can be quoted. In 1933 the Latvians bought a British tramp and immediately reduced her crew by 33 per cent. They had no difficulty in securing seamen at £1 a month owing to the severe unemployment in Latvia. When it is remembered that the National Maritime Board scale for a British A.B. is well over £8 a month it is easy to understand what British shipping has to face.

The cheaply-

towards coal bills, but not as a rule. The other handicap is insurance, for knowledgeable underwriters in their own interests handicap a ship which is obviously decrepit. Unfortunately this handicap is limited by several factors. First there are many underwriters who are not knowledgeable; secondly, there are many who are not free agents because of collective agreements; and, thirdly, the owners of such tonnage insure as little as possible and the burden generally falls on the cargo owners only. Up-

It is necessary, however, for the owner always to keep in mind a careful balance, for every hundred pounds which he spends on the new ship in this search for running economy is shown in her accounts all through her career in the shape of overhead expenses. As the effective life of a tramp is rarely more than twenty years under the British flag, the owner must reckon on a 5 per cent depreciation being within the reach of his accounts.

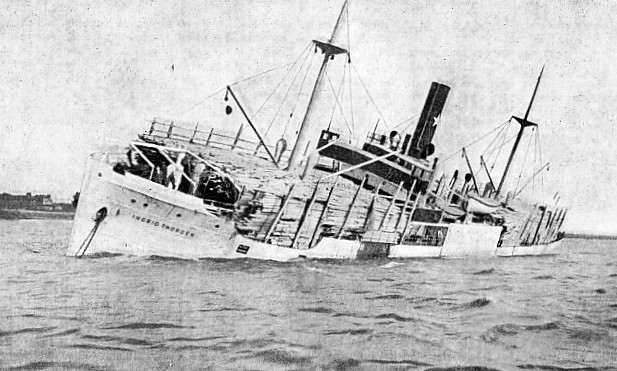

A TIMBER SHIP’S LIST may be due to many causes in addition to the heavy deck load, but nearly all timber carriers develop such a list when entering port. The Ingrid Thorden is a Swedish vessel of 1,885 tons gross. She has a length of 262 feet, a beam of 42 ft. 8 in. and a moulded depth of 20 ft. 6 in. She was built at Gothenburg in 1920.

Twenty years is a long time to look ahead and the problem of the tramp would be greatly simplified if it were possible to build a ship calculated to last five years at a quarter of the present cost. Considerations of safety forbid this being attempted, even if it were feasible.

The owner, therefore, ties up a lot of money in an up-

It is true that the owner then lays up his ship at the minimum of expense, and that the liner owner has to keep his running whether she is full or empty; but the tramp has not the protection of the liner conferences and only recently have minimum freights been established in a few trades. This is a new principle whose fate is still in the balance.

The most obvious means of reducing running expenses are by improvements in the engine-

The standard cargo ship engine for nearly forty years was the three-

Costly Speed

There are any number of these devices on the market, some only a slight improvement and some revolutionary. Shipping has been so hard hit during the period when these improvements have been appearing on the market that the inventors have often been forced to prove their claims at their own expense. They have not hesitated to do so, either by installing their plant in ships of their own or else by fitting it on a “no cure no pay” principle, undertaking to make no charge if their claim for economy is not fully justified. No device, however ingenious, is an economy unless it raises the ratio of earning power to capital outlay. The faster tramp does not receive any higher rates than the slower one, although she may be able to get several more paid passages into the year. Also, speed may be costly, for while an increase from 10 to 12 knots is only 20 per cent, the faster ship costs roughly 70 per cent more to maintain.

To mention only a few modern devices out of many, the Lentz engine for ships of moderate power, using poppet valves and superheated steam, usually guarantees a fuel saving of from 20 to 25 per cent. In many ships an economy of 30 per cent has been obtained.

Such improved valves as Andrews and Cameron’s quadruple opening balanced slide valves save a lot of fuel. Turbo-

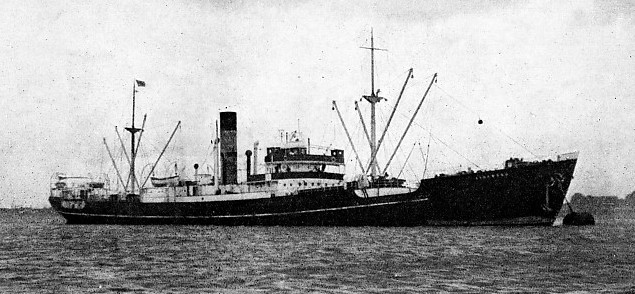

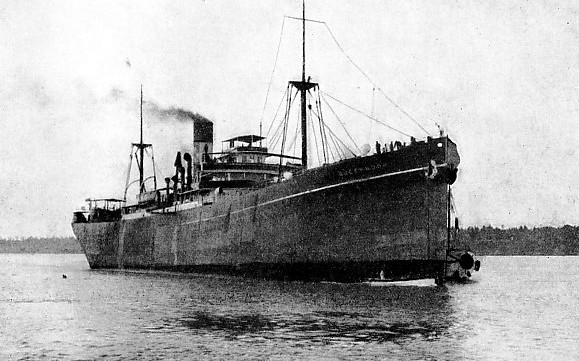

A MAIERFORM BOW was fitted to the Kirnwood, a vessel of 3,817 tons gross belonging to the Joseph Constantine Steamship Line. Improvement in hull forms is a remarkable feature of the modern tramp The Kirnwood was built in 1928, and has a length of 389 ft. 7 in., a beam of 52 ft. 6 in. and a moulded depth of 24 ft. 3 in. She is registered at Middlesbrough, Yorkshire.

There are several forms of improved reciprocating engine, including the C.M.E.W. quadropod engine, Stephens’s and others. Great interest has been aroused by White’s engine, a combination of high-

In the ordinary exhaust turbine fitted to so many tramps the reciprocating engine is of ordinary weight and type, driving the shaft direct. Only the turbine is geared.

Despite all these improvements, there are authorities who believe that the most useful machinery for the tramp is the triple-

The tramp tries to buy her fuel in the cheapest market, and when she does secure a favourable quotation she will take in as much as she possibly can without interfering with her carrying capacity. Since the war of 1914-

The fitting of this appliance, which is not by any means elaborate, was encouraged by a number of strikes which made the supply of bunker coal uncertain, although the owners did not want to turn to oil exclusively with the possibility of its price going up. On many occasions the installation has been fully justified, but other owners have found that the oil-

Improved Hull Forms

While all these improvements in the engine-

As the hull is always the most expensive item in a ship it is surprising that so little attention was devoted to tramp hulls for many years. The standard “cut off by the yard” form was considered to be good enough and to carry the maximum of cargo. Fine lines appeared only to be waste of hold

space, although if they reduced the necessary horse-

The idea of spending much money on tank experiments for every separate hull design was not considered. Such refinements were thought suitable for men-

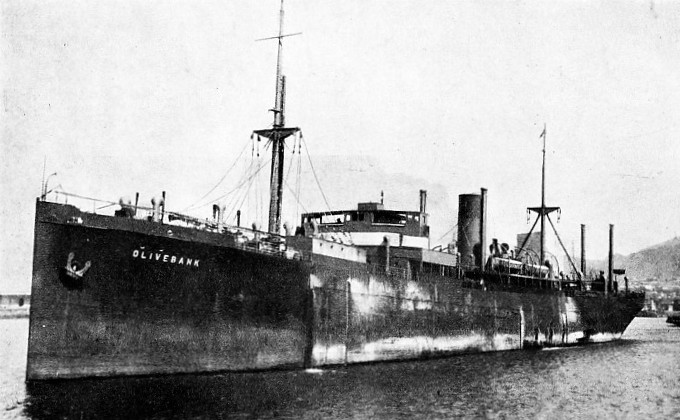

BUILT AT GLASGOW, the Bank Line motorship Olivebank, of 5,154 tons gross, dates from 1926. Her owners, Andrew Weir and Company, were also the owners of the well-

This has produced a hull which is far more sightly than the fashion of twenty years before. Forward the sides are given a flare which helps to lift the ship over the waves. Aft, where the lines mean much more to speed than they do forward, there has been a conspicuous fining which shows its influence in the wake when the ship is under way. Every effort is made to keep the propeller submerged when the ship is in ballast instead of letting it project out of the water to half its diameter, making a great thrashing of white spray and losing power. These features and improvements are comparable to the minor gadgets and fittings which improve the efficiency and economy of an ordinary triple-

Streamlining to reduce the effect of the air resistance makes little difference to a tramp, but below water it is different. Not only is the resistance of the hull and its excrescences to the water reduced as far as possible, but also many devices have been evolved to increase the efficiency of the propeller by improving the stream of water in which it works.

The pro-

The rudder is shaped to continue this effect — at the top slightly inclined to starboard and at the bottom to port, although its axis is vertical. By this means designers contrived to avoid direct resistance and its consequent eddy and disturbance in which the propeller cannot do its best work.

Somewhat similar in principle is the wing fin, in the shape of a small curved bilge keel which diverts the run of the water so that it reaches the propeller virtually square, and not in an upward direction as it is made to do by the normal stern lines of a ship.

Streamlined Rudders

Another interesting feature of that kind is the Star contra-

This is fitted in the space between the propeller and the stern post, with only a few inches of clearance, and acts as a guide which greatly reduces the turbulence of the water passing the rudder, reducing the percentage of slip (wasted effort by the screw) and improving steering.

Steering and the rudder can have much influence on the economy of a ship. Many miles can be added to the ship’s run in a single day if she is yawing madly instead of steering a straight course, and it has been established beyond doubt that the single plate rudder in use for so many years is wasteful in many ways. Far more efficient is a streamlined rudder. Balanced rudders, in which part or the surface is forward of the axis, demand less power in the steering engine and consequently less fuel. The Oertz rudder is popular in modern ships and is fitted in some of the largest liners. Its cross-

While all these innovations improve the efficiency of the hull they also have a tendency to force up its cost, but nowadays the builder saves all the money that he can by standardization, not only in the various fittings which he puts into the ship but also in the hull itself, saving much money on such things as templets and patterns.

Among other establishments, the Burntisland Shipyard, on the Firth of Forth, has become famous for its “Economy” type of cargo steamer which was evolved after a thorough investigation into the problems of efficient ship propulsion. It is not a standardized type but is built in many sizes, with particular features for particular trades, such as the London coal trade.

ONE OF THE MOOR LINE FLEET, the Queenmoor was built at South Shields, Co. Durham, on the River Tyne, in 1924. A vessel of 4,863 tons gross, she had a length of 405 feet between perpendiculars, a beam of 53 ft. 7 in. and a depth of 26 ft. 6 in.

Its principles are the most perfect possible streamline flow and the ideal inflow to the propeller. This reduces the fuel consumption, so that the ship carries more cargo, due to having smaller bunkers. The engine-

Other shipyards have worked to the same end, and J. and C. Harrison, of London, were among the first tramp owners to get the full benefit. They ordered a large number of big ships when the shipbuilding slump was at its worst and the yards were willing to quote low prices.

These Harrison ships are not all sisters and, although their hulls are designed on the same general principles as the Burntisland “Economy” type ships, a good deal of money has been spent on special fittings.

Ever since the war of 1914-

Recently, however, there has been a big change of opinion, and the majority of the tramps built under the British “scrap-

The main factor of the success of these ships has been that the firm has produced a standardized diesel which is not only simple for management by an average crew, but is also exceedingly compact, allows for larger holds at the expense of machinery space, and is made light by the use of welding.

Better Quarters for Crews

This Doxford diesel engine has three cylinders with opposed pistons. The explosion between the upper and lower pistons forces them in opposite directions simultaneously. The engine develops 1,800 brake horse-

The great improvements during the last few years have increased the problem of personnel. A technically trained man demands better quarters and living conditions than contented the older type. There are still many tramps afloat in which there is a good deal to be desired in the topgallant forecastle forward, separated from the working positions of the crew by a fore well-

The motor tramp Peebles, for example, has separate rooms for day men and night men, so that nobody’s sleep is disturbed. There are separate mess-

In the years which immediately followed the war of 1914-

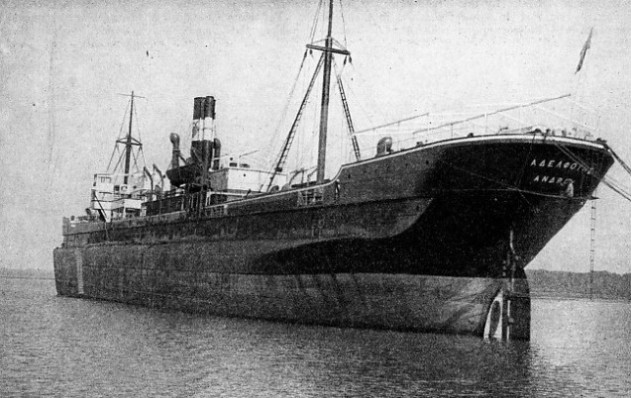

A GREEK TRAMP STEAMER built by Doxford and Sons as the Penrose in 1903. When sold to her Greek owners she was renamed the Adelphotes and registered at Andros. This photograph shows her at Pin Mill, near Ipswich, Suffolk. Of 3,882 tons gross, she is 350 feet long, 49 ft. 1 in. in beam and 23 ft. 10 in. in depth. She is one of the few surviving “turret deck” ships once popular.

You can read more on “British Shipping”, “The Peebles” and “Progress of the Motorship” on this website.