© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

The Unlucky K 13

On January 29, 1917, the trials of K 13, a new submarine, were carried out in the Gareloch, on the Firth of Clyde. Without warning, the great submarine sank, but heroic measures saved the lives of over half the number of those on board

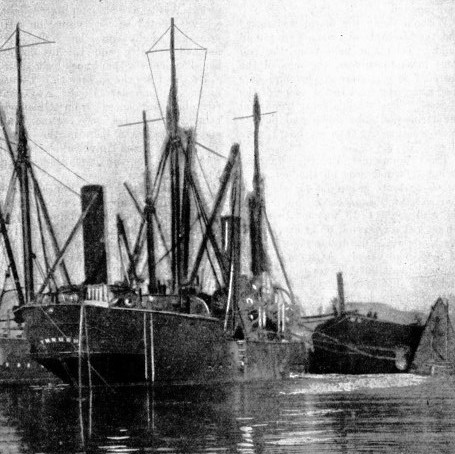

WITH HER STERN EMBEDDED deeply in mud, the bows of K 13 rose above the surface of the water. Two of the salvage vessels are shown above with K 13’s bows secured between them. Inside the wrecked submarine eighty men were trapped. After fifty-

WHEN K 13 slid down the slipway of the Fairfield Works into the waters of the Clyde in 1916, she was without doubt one of the most remarkable submarines built up to that time. She was a big vessel of 2,600 tons displacement and had a length of 334 feet. She was almost large enough to be described as a submersible cruiser. Her sharp bow and fine lines gave a hint of her most astonishing speed.

The comparative slowness of submarines had hitherto hindered cooperation with surface vessels. In K 13 the designers had succeeded in producing a vessel that could hold her own with battleships and cruisers on the surface and steam at a speed of about 26 knots. This amazing feat was achieved by a remarkable innovation in the machinery. Steam turbines were installed for propelling her on the surface and she was therefore equipped with two stumpy funnels that were lowered when she was diving. Kv 13 was thus the thirteenth of a new type of submarine, and the designers and builders and the Admiralty were anxious to see how far their secret submarine would come up to expectations.

She was taken out on December 29, 1916, to the Gareloch, on the Firth of Clyde, where there was no chance of any enemy agents becoming witnesses of the tests.

Her trials took place on Monday, January 29, 1917. She dived to 83 feet and was under the surface for two hours while the experts tested everything aboard. The only things they were unable to check were the boiler-

As the Fairfield Works were building a sister ship, K 14, Commander F. H. Goodhart, D.S.O., who was to be in command of K 14, and Engineer Lieutenant Rideal, who was to be engineer, were on board K 13 to learn as much as they could about her. In all she contained fifty-

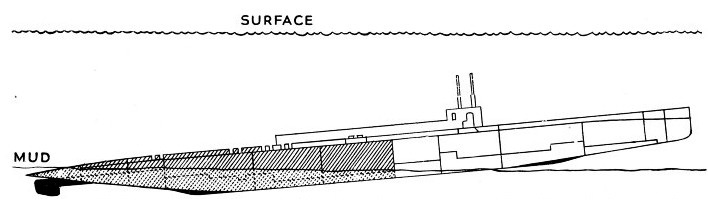

DIAGRAM SHOWING THE POSITION OF K 13 when she first sank. The after compartments of the submarine, shaded in the diagram, were flooded because of the neglect to close the boiler-

In a few seconds the men in the control room saw the needles on the depth gauges moving unaccountably fast. They felt an unpleasant and unexpected pressure on their eardrums, and knew that something had gone wrong. “Blow all tanks”, ordered Commander Herbert at once.

The water was blown out of the tanks by means of compressed air, but still the depth gauges told the men in the conning-

The vessel had two keels weighing ten tons each. These could be released in an emergency. The fact that they were ordered to be released told Mr. Hillhouse and the other officials in the control tower that they were facing a disaster.

A Disastrous Oversight

Along one side of the boiler-

While the voice pipes leading to the after parts of the ship were being closed a strong jet of water shot over to the switchboard, and in a moment the place was full of choking smoke caused by fuses blowing out and cables blazing. With great presence of mind someone seized sacks and rammed them into the pipes to stop the water from spurting out while the pipes were being shut.

Half deaf because of the air pressure, choking with the heat and the smoke, they strove to get at the burning cables, and extinguish the flames with wet sacks. The first man to try received innumerable shocks, due to the short circuiting of the wires. Another man pulled out a drawer from the chart-

By now K 13 was quite still and her depth gauges showed that she was resting on the bottom at a depth of 55 feet. The disaster was due to the oversight of someone who had forgotten to close the four ventilators of the boiler-

In the unflooded compartments of the ship there survived forty-

It seemed that in about eight hours all the oxygen in the ship would be exhausted. Unless the men were rescued, could bring the ship to the surface, or could otherwise make their escape they were then apparently doomed.

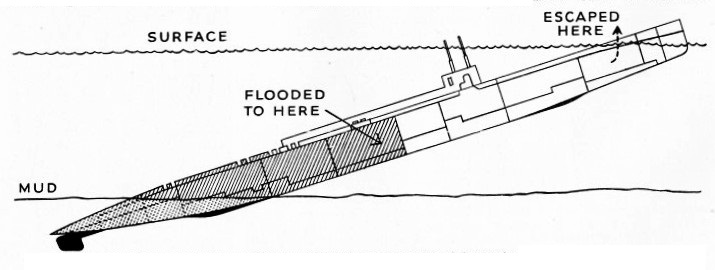

AFTER THE FORWARD BALLAST TANKS HAD BEEN EMPTIED by means of compressed air, the submarine K 13 took up the position shown in this diagram, with her bow and her two periscopes thrusting above the surface of the water. A photograph of the submarine in this position is shown on page 673. The trapped men eventually escaped from the forward compartment.

The experts of Fairfield’s and the naval officers did their best to bring K 13 to the surface. They used up as much of the compressed air as they dared in the attempt to blow the water from the forward tanks. It made no difference to the position of the submarine. She still stuck fast. If only they could have reached the valves controlling the tanks in the stern of the ship they could have brought her up again, but these were in the flooded engine-

The naval officers and officials summed up the situation. The light was going. Even if they were lucky they could not expect any one from the surface to make contact with them until next morning, some eighteen hours later. As apparently there was only enough oxygen to last them about eight hours, they did not appear to have the slightest chance.

Calmly, however, they began cautiously to test the water-

Fortunately for them the commander of the submarine E 50 saw them dive and, in his own words, “did not like the look of it”. He promptly dropped a buoy to mark the spot where he saw K 13 disappear. He met the steamer Comet and on board her he found a Fairfield director gravely concerned at the quantity of air that came up as the ship went down. This was the air that had been forced from the after compartments as they were flooded.

Without delay the alarm was raised and the attempts at rescue were put in hand. Telephone bells rang, the call went forth for divers, the men of the Fairfield Works were roused and cars sped along the road to the scene of the disaster. The world’s most wonderful submarine had gone down and no one knew whether the men on board were alive or dead.

The commander of the gunboat Gossamer, which was on the loch, gave orders to start grappling for the submarine. At 2 a.m., eleven hours after she had sunk, K 13 was located. By 4 a.m. a diver arrived on the scene and at once put on an old diving suit and tried to reach the vessel. As he was going down the suit burst under the pressure and they just managed to get him up in time to save his life.

Without delay a car was sent from Shandon to get the diving suit from the Fairfield Works, twenty-

By this time the salvage ship Thrush under Commander I. J. Kay was steaming full speed from Greenock, bringing with her two lifting craft and a trawler to help in the rescue operations. From Holyhead the famous Ranger was hastening with Commodore Young.

All night long the men imprisoned in K 13 were lying about the floor, sitting in chairs, crowding in the bunks, trying to find the easiest position in which to breathe. As the air grew worse many of them sank into an apathy, panting heavily as though they were running a race, their lungs working faster in an effort to obtain enough oxygen from the air to keep them alive. When daylight came and the diver knocked on the hull, they were all half dead from the foul air.

That they were still alive was something of a miracle. With air theoretically sufficient to last about eight hours, they still survived after fifteen hours. This was mainly due to the skill of Mr. W. McLean, the manager of the Fairfield submarine department. Now and again he allowed a little compressed air to escape from a container to keep them alive. Then he withdrew some of the foul air from the torpedo room and forced it back with the air compressor into the empty steel bottles. That day the air grew so foul that there was not sufficient oxygen in it to allow a match to flame up.

That they were still alive was something of a miracle. With air theoretically sufficient to last about eight hours, they still survived after fifteen hours. This was mainly due to the skill of Mr. W. McLean, the manager of the Fairfield submarine department. Now and again he allowed a little compressed air to escape from a container to keep them alive. Then he withdrew some of the foul air from the torpedo room and forced it back with the air compressor into the empty steel bottles. That day the air grew so foul that there was not sufficient oxygen in it to allow a match to flame up.

THE SALVED SUBMARINE K 13 lying between two of the lifting vessels before being taken into dock. Only a few hours after the men trapped in her had been rescued she tore away her cables and sank once more to the bottom. The salvage men worked on her for six weeks before she came to the surface again.

Hourly the situation grew more desperate and at last Commander Goodhart and Commander Herbert made up their minds that one of them should attempt to reach the surface to help the rescue operations by giving full details of the position inside the ship. The conning-

It was hoped that Goodhart would make his way through the conning-

The plan was feasible, although it called for a good deal of manipulation of the pipes and valves leading into the conning-

Having removed some of their clothes, the two naval officers entered the conning-

Goodhart judged that the air pressure was sufficient to enable him to raise the hatch and prepared to go. He ducked from the dome to the hatch, and was gone.

Commander Herbert at once reached to close the hatch again, but the compressed air, exploding upwards, whipped him off his feet as though he were a feather, and swept him up through the wheelhouse hatch and away to the surface almost before he knew what was happening. He barely missed the diving boat as he came up, and a diver, standing on the diving ladder, grabbed him and hauled him aboard.

“Where’s Goodhart?” were his first words.

“We don’t know”, was the reply, and Herbert realized that the companion of his hazardous mission must be dead.

The body of Goodhart was afterwards found in the wheelhouse. It was obvious that he had been dashed to death against the wheelhouse roof by the force of the compressed air.

Commander Herbert began to describe the position below and give the rescuers the details that were so essential if their efforts were to succeed. Not until he had told them everything of importance would he consent to be taken ashore.

The rescuers were baffled by the vast size and weight of the submarine. If she had weighed only 500 tons or even 1,000 tons they might perhaps have picked her up bodily; but they could not attempt it with K 13.

Meanwhile the divers were risking their lives down below, slithering about in mud up to their armpits. They had to fix cables under the bow to see whether they could lift it up to the surface while leaving the stern resting on the bottom. The submarine was more than a hundred yards long, and if her bow could be raised ten or twelve degrees her nose would appear above water and the imprisoned men could be cut out.

The mud piled up over the stern for a dozen feet and sealed her firmly to the bottom as though it were determined to hold her for ever and bury her completely.

The men had been trapped on the sea-

The most urgent necessity was to get a supply of fresh air to the prisoners, for it seemed impossible that they could last much longer. Once this were done the problem of getting them out could be tackled with every prospect of success.

The most urgent necessity was to get a supply of fresh air to the prisoners, for it seemed impossible that they could last much longer. Once this were done the problem of getting them out could be tackled with every prospect of success.

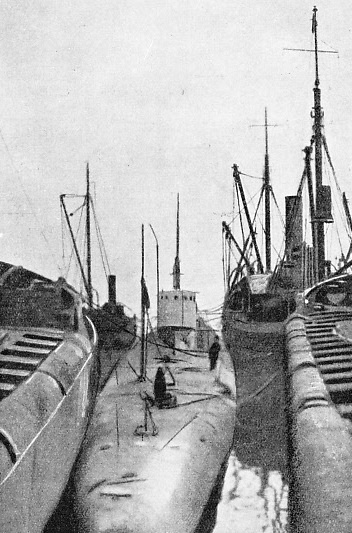

THE BOW OF K 13 rising above the surface of the water (right). The imprisoned men were rescued when a hole was cut through her plates with oxy-

Mr. Lipton, with his intimate knowledge of the pipes of K13, selected his points because either had two water-

Fortunately, there were fittings from the sister ship K 14 available to help this plan, and Mr. Lipton hurried to the works to obtain them and get other fittings made in the machine shop. They all worked valiantly against time. Darkness came down and the arc lamps lit up the scene as the rescuers waited anxiously for the divers to make the connexions. The imprisoned men were stirred from their lethargy by a tapping on the hull that told them an air connexion had been made.

They carefully opened the valve and saw water gush through. They thought it was merely a little seepage, so they filled a bucket, and then another and another, expecting each time that the water would cease to flow. As it continued they were obliged to close the valve and tap a message in Morse to the diver to tell him what had happened. Then they dropped down to wait and hope, while the diver struggled in the darkness to disconnect the pipe and find out what had gone wrong.

At 4 a.m. on the Wednesday the men in K 13 were roused again by the tapping of the diver. Cautiously they turned the valve and to their joy they heard the air hissing through. They crowded round, breathing in the pure air, unable to get enough of it. Even those who were in the sorriest state quickly began to revive as the fresh air gushed in.

Up on the surface, under the vivid glow of the arc lamps, the rescuers looked with amazement as the foul air came gushing from the vent pipe they had installed. It was as black and thick as smoke and they marvelled how any man could breathe it and live.

Directly they had recovered, the imprisoned men set about trying to save themselves in real earnest. There was no longer any lack of air, so they began to charge up the compressed air bottles to their full pressure of 2,500 lb. to the square inch.

The great cables from the salvage vessels were straining away at the bow, trying to lift it, but all these efforts made little difference. Now the imprisoned men began to turn on the compressed air to empty the seven external forward ballast tanks. Into one tank after another they turned the compressed air until they guessed that almost every tank was empty. They watched the spirit levels that told them whether they were on an even keel, or whether their bow was rising; but the air bubbles in the levels did not stir.

Gloom settled down on them once more as they connected up to the last tank. They were starting to blow it when they saw the little bubble of the indicator begin to move, and the bow of K 13 rose to the surface.

A bottle of brandy was passed down the pipe to the trapped men and chocolate and milk followed. As there were no cups or tumblers on board, they screwed off the end of an electric torch and used it to give every man a nip of brandy.

When the nose of K 13 pushed up above the surface, the cables beneath her were hauled tight; and the rescuers faced the problem of getting the men out. They were afraid that something might carry away and let the bow slide under, or that the fine weather would break and bring disaster to all imprisoned in the ship. Minutes were precious. By now the electric light had failed and the prisoners waited patiently in the dark for deliverance. First a torpedo hatch was suggested as a way out, but it was found to be impassable. Then the rescuers were baffled by the water between the outer and inner hulls until Commander Herbert asked the prisoners to investigate a certain valve that was found to be open.

“We shan’t be long now”, came a voice down the voice pipe, and the eyes of the imprisoned men turned upward to watch for the first sign. It came at last when a point of light from an oxy-

One by one the imprisoned men made their way back to li fe, while cheer after cheer resounded among the rescuers, foremost among whom was Commander Herbert.

fe, while cheer after cheer resounded among the rescuers, foremost among whom was Commander Herbert.

The forty-

Next day one of the maids in the Shandon Hydropathic Establishment mentioned to Mr. Hillhouse that she had seen two men swimming in the loch on the Monday afternoon. They had thrown up their hands and after having given a shout they had disappeared.

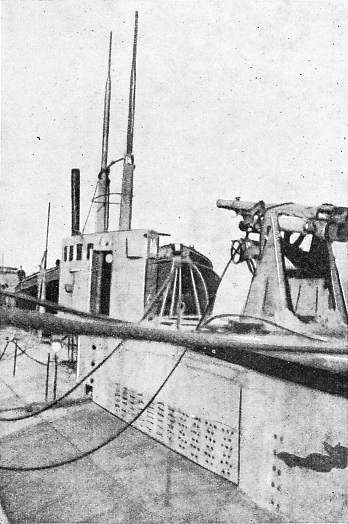

THE PERISCOPES AND CONNING-

We know now that this maid was the witness of the escape of two brave men, Engineer Lieutenant Lane and John Steel, the foreman engineer of Fairfields, from the engine-

A few hours after the survivors of K 13 had been rescued, she suddenly sank to the bottom .again. It took the salvage section six weeks to drive out the water. In the end she broke unexpectedly from the grip of the mud. When she was put into commission again she was given a new number

You can read more on “Beneath the Surface”, “Epics of the Submarines” and

“Rasing a Submarine Minelayer” on this website.