© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Raising a Submarine Minelayer

An exciting chapter was added to the history of salvage when, in 1917, Commander Davis raised from the sea bed and beached on the Irish Coast a submarine that was loaded with live mines

THE MINE-

IN 1917, when the enemy submarines were taking such a toll of British shipping, the least bit of information concerning the movements of the U-

Not only were the stealthy U-

Fleets of minesweepers went out regularly to sweep the channels and ensure that they were free of mines before any ships were allowed to pass along them. Submarine commanders, however, sometimes watched through their periscopes until they saw the sweepers complete their job, and then the submarines followed in their tracks to lay a batch of mines. As soon as the sweepers returned to harbour to report “all clear”, the steamers would venture out, with the result that more ships would go to the bottom.

Such mishaps were inclined to raise in the mind of the naval command a doubt whether the sweepers had done their job properly. As for the sweepers that had gone to the trouble of sweeping the channel, they spared no pains to get even with the enemy. From observation the patrols learned to know when a minelayer might be expected to lay a new batch of mines in a particular area, and occasionally the minesweepers pretended to sweep up the mines and deliberately refrained from doing so, with the result that some enemy submarines were blown up by striking against their own mines.

One of the main areas in which the submarine minelayers operated was on the route across the Irish Sea from Waterford to England. Hundreds of live cattle were being shipped regularly from the Irish port to feed the English people, and the enemy did their best to stop the shipments by surreptitious minelaying. A submarine usually came along about once a month to eject its deadly cargo. This sufficed to imprison all the steamers in the port until the naval command was satisfied the danger was removed. On Saturday, August 4, 1917, the sea off Waterford was as smooth as it could be. The local fishermen along the coast were keenly interested in the movements of the submarines. Just before midnight, when one or two fishermen were standing before the doors of their cabins, they heard a terrific explosion at sea. It reverberated along the coast for miles. The noise of the explosion had barely died away when faint cries were heard coming over the sea.

What it was, or what had happened, nobody knew, but several fishermen raced quickly to launch their boats and find out. In a short time three fishing boats were being pulled as fast as the fishermen could row in the direction whence the sound came. Spreading out in a line, they searched the seas. About four miles from the shore they heard a cry that drew their attention to something dark on the waters, and it was not long before the nearest boat hauled a man on board. Had it taken them much longer to find him he must have drowned, for he was exhausted. Heaping clothes over him to keep him warm, the fishermen pulled ashore. There the authorities took the man into their keeping for the rest of the war.

This man turned out to be Captain Tebbenjohanns of the UC 44. He had laid a batch of eight mines, when the ninth slid out of the launching chute and must have made contact with another mine. Whether this mine was one of his own, or whether it was one that had been laid previously, it is difficult to determine.

The greater part of the stern of the U-

No sooner did the naval authorities at Waterford learn about the loss of the UC 44 than the order went forth to salve her. It was early on Sunday morning before they could gather what had really happened. On Monday, August 6, Commander G. Davis, whose work for the Salvage Section had already brought him to notice, was called upon to relinquish another job on which he was working and proceed without delay to Waterford to raise the U-

It was midnight on Tuesday when Commander Davis drew into Waterford harbour and made ready for the morning. At dawn the naval authority ordered the minesweepers to clear a passage so that Commander Davis could go out to investigate.

Although the minesweepers had been at work since the UC 44 blew up, the wisdom of this precaution was soon proved, for one of the unlucky sweepers herself hit a mine and sank.

Commander Davis went out with his salvage ship and trained men and quietly lifted the minesweeper and brought her back to shore.

Commander Davis went out with his salvage ship and trained men and quietly lifted the minesweeper and brought her back to shore.

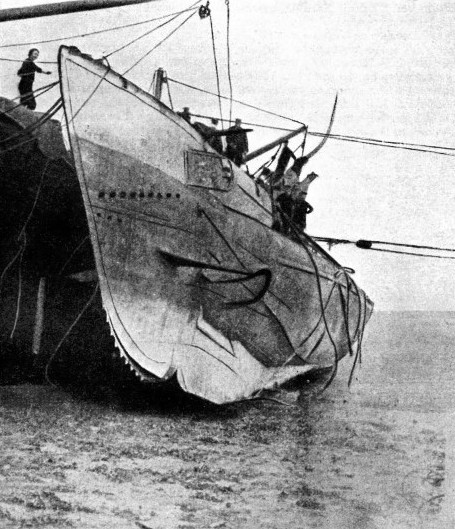

BEACHED NEAR WATERFORD, in Ireland. After the salvage vessels had raised her. loaded with live mines, from a depth of ninety feet, the submarine UC 44 revealed to the British Admiralty many important features of German submarine design. The serrated teeth on her bows, for instance, were intended to cut through the anti-

This done, he dropped his grapnels and began to drag them over the area in which the submarine sank. After he had steamed back and forth for a time his grapnels caught. He buoyed the spot and a diver went down to see what was there. It was, as they expected and hoped, the UC 44. She was lying in ninety feet of water broadside on to the current that made it so hard for the divers to work. The difficulties of the task, however, made Commander Davis all the more determined to prove his skill.

The depredations of the submarines caused such serious alarm that the Admiralty was doubtful as to what the end would be. The naval authorities wanted this particular submarine, if they could get it, for several purposes. In the first place, they were anxious to see how the enemy were developing their minelaying submarines, so that the naval architects could study its weak and its strong points. They hoped that from it they might learn a method of countering its activities. There was also the chance that the papers had not been destroyed by the explosion. Thus the instructions given to the commander might prove of primary importance, for if the Admiralty learned what the submarines were instructed to do they might use this inside information to destroy the U-

We know now what Commander Davis did not know then -

Commander Davis concluded that the best method of tackling the job was to work a number of cables under the U-

It was this simple and clever way of using the power of the sea to recover a sunken ship that Commander Davis employed. A cable was suspended between his ships and a loop of the cable was dropped to the seabed. This loop was dragged along until it worked under the submarine into the exact position desired. As soon as this was done, a buoy was fastened to either end of the cable. Another cable was then swept into place, and yet another, until a row of strong steel cables lay at intervals under the U-

Lifted by the Tide

This task took the salvage crew just nine days. They turned in that night thinking that the back of the job was broken, but the weather ruled otherwise, for in its usual perverse way it began to blow a gale. The wind continued for twenty-

and drakes with the buoys at the ends of the cables. They picked up the dropped ends and sorted out the cables that had become entangled, until their buoys once more lay in two neat parallel rows. Between these rows they towed and anchored one of the special lifting craft that came into existence during this war.

These lifting craft were originally huge flat-

BETWEEN THESE LIFTING VESSELS the UC 44 was brought ashore. Cables were slung beneath the wreck to form a cradle, and these cables were attached to the lifting vessels at low tide. The force of the rising tide lifted the vessels together with the wreck, which was carried inshore until it touched bottom again. This process was repeated until the wreck was finally beached.

Commander Davis fixed the buoyed ends of the cables to the special attachments down either side of his lifting vessel. As the tide touched the lowest point of the ebb, every cable was tightened to its limit. This left the lifting craft floating directly over the submarine as it lay in the cradle of cables under the salvage vessel. While the tide was rising the water in the tanks of the lifting vessel was driven out by compressed air, and after a time Commander Davis was gratified to find that the UC 44 was moving clear of the bottom. After an hour or two the salvage officer began to tow her toward the shore while the tide still flowed, so that, as she moved slowly along, the tide would raise her farther from the bottom and thus enable him to travel a greater distance. By the time they had moved her three-

Once again they tightened the lifting cables as much as possible and began to tow the submarine shorewards as soon as the clearance was sufficient. At one time she bumped on the bottom and they held their breaths, expecting one of her mines to explode; but nothing happened, and they continued the work. They gained another three-

The salvage workers knew all about the live mines on board and were aware that death might overtake them at any moment. They exercised all possible care to avoid calamity. One day as she was moved slowly along, the submarine slipped out of her cradle of cables and dropped on the seabed. The men braced themselves for the explosion for a few tense seconds; but luck was with them, and they breathed again. Then began the task of picking her up again.

Bight in their path lay a sandbank that sloped steeply upward for 14 feet. It was a most difficult obstacle to negotiate. If they had gone on towing the wreck without altering its trim the submarine would have bumped her nose into the bank. It was therefore essential, before they could lift her up this bank, to raise the nose of the submarine by shortening the slings until the angle at which she was being carried conformed to the slope of the bank. This entailed another risk, for she might slide out backwards through the cables.

Dangers of Unloading

Commander Davis placed one lifting-

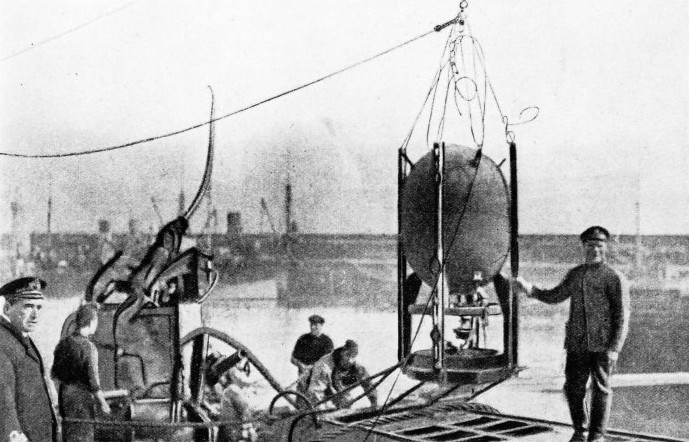

Inside the submarine they found nine gigantic mines. These had to be handled with extreme care until they were rendered innocuous by the salvage officer. In addition there were several torpedoes and many shells for the gun mounted on her deck. The after portion of the vessel was blown right off, and a shattered mass of plates sagged at the broken end as if it had been so much matchboarding.

Commander Davis fully earned the Distinguished Service Cross that he won, for he brought ashore confidential papers of priceless value. These papers revealed the ruse that the enemy had adopted to deceive the British Admiralty into thinking that the submarine defences across the Straits of Dover were driving the submarines right round the north of Scotland.

The papers stated that it was best for the U-

This proof that the Dover submarine defences were not stopping the U-

AN UNEXPLODED MINE being raised from the wreck of the salved submarine UC44. The submarine had nine live mines on board when she was wrecked in September 1917. Commander G. Davis -

You can read more on “Dramas of Salvage”, “A Trinity of Dramatic Exploits” and

“The Unlucky K 13” on this website.