© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Seven Years Under the Sea: the “Laurentic”

Constantly risking death and injury, courageous men continued to search for and to retrieve bullion from the shattered hull of the sunken White Star Liner “Laurentic”

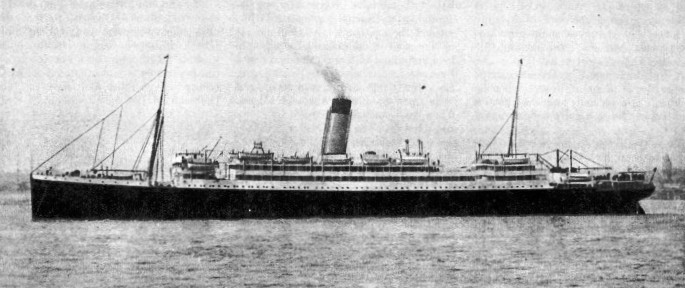

BEFORE THE DISASTER. The Laurentic, a White Star liner that operated between Liverpool and Canada before the war of 1914-

One day in January, 1917, the Laurentic, an Atlantic liner of 15,000 tons gross, sailed from Liverpool for Halifax, Nova Scotia, with gold bars worth over £5,000,000. Not long afterwards she struck a mine off Malin Head, Co. Donegal, on the north Irish coast, and sank almost immediately. Many of those who managed to escape in the boats died of exposure in the bitter weather. No fewer than 354 out of a complement of 475 officers and men lost their lives.

Practically all of the gold was recovered. This chapter tells the story of its salvage.

In magnitude and sustained effort the deep-

Because of its lavish expenditure on the war of 1914-

At the outbreak of war the Laurentic was a White Star liner designed for the St. Lawrence service. As she was a handy ship with a good turn of speed, she was converted by the Admiralty into an auxiliary cruiser by the addition of a gun or two.

By the middle of December, 1916, the British Treasury was preparing to send £5,000,000 in gold across the Atlantic. The United States had not then declared war on Germany. But American as well as Canadian factories were working twenty-

In August, 1906, Commander Damant, one of the cleverest diving experts in the British Navy, had made diving history by reaching a depth of 210 feet. To carry out some experiments for the Admiralty, he had risked his life to go deeper than man had ever gone before.

In those days it was not unusual for divers to become unconscious under water. Moreover, after coming up, their bodies and joints were frequently racked by excruciating pains that were known as “bends”. Some divers became paralysed for life. The late Professor J. S. Haldane was asked to trace the scientific cause of these dangerous conditions. Commander Damant, then Inspector of Diving for the Royal Navy, and a naval gunner, Mr. A. Y. Catto, more than once risked their lives to carry out the diving part of the tests.

It was found that the diver grew unconscious under water because too little air was being pumped down to him, and that “bends” and paralysis were caused by bubbles of nitrogen gas in the blood, due to breathing compressed air. This painful and dangerous compressed-

Eleven years after Commander Damant had undertaken these experiments he was asked to carry out the greatest treasure-

Had the Laurentic been in a sheltered position, Commander Damant and his divers would have had little difficulty in dealing with her; but diving in still or sheltered waters and in the open sea are two different propositions. The Laurentic was subject to all the idiosyncrasies of wind and tide. Lacking shelter on the east, where the nearest point was the coast of Scotland, there was nothing to protect her from gales sweeping down from the North Pole or raging across the Atlantic. Moreover, she was also lying to the north of Lough Swilly, which a southerly gale could heap up to make the position untenable for divers. She could thus be assailed by gales on every side.

The difficulties and the risks were obvious; but, as the Navy had been ordered to recover the gold, Commander Damant began operations without delay. The first diver who went down to prospect the ship found her in a most awkward position. She was neither on her side nor on an even keel, and it was impossible to walk on her side or on her deck, for both were sloping too steeply. Clinging to the rail at the apex was the only means the divers had of working along the length of the ship -

The steep angle of the deck, and the obstructions that were liable to catch in the pipes and lines of the divers, made it unwise as well as risky to attempt to reach the gold through the deck openings. Fortunately there was a loading port in the ship’s hull which promised an easy entrance to the baggage room. With no obstructions above it or near it to foul the divers’ lines, it had been made specifically for loading cargo and baggage into the ship. A charge of explosive ought to open it and leave a clear passage to the gold.

The doors were duly blown off their hinges into the interior of the passage. As they had been made to fit tightly, it was a difficult task to shackle them up to the cable that was lowered from the Racer and to manoeuvre them through the opening. A bit of a sea made matters worse by whipping about the heaving wire. This wedged the doors several times, because they rose or dropped at inopportune moments.

Directly the doors had been removed all sorts of cases and barrels began to bob up to the surface from the interior of the ship. Displaced by the sinking of the vessel, the buoyant casks and cases floated into this passage, from which they rose to the surface as soon as they could escape.

A surprising amount of stuff was wedged behind the objects that floated clear. With crowbars and hammers the divers began to lever out this wreckage and remove it. They found sacks of flour which had barely suffered at all, although they had been at the bottom of the sea for six weeks.

The sea, soaking into the flour for about two inches, had turned it into an impermeable covering that had sufficed to keep the rest of the flour as dry as when it had come from the mill. It was then the month of March, and the divers expected bad weather, which they duly experienced. The equinoctial gales whistled in the rigging of the Racer and snow and wind harassed the salvors. It was possible to work only when the weather abated. At other times they sought the shelter of Lough Swilly and waited for better conditions.

The sea, soaking into the flour for about two inches, had turned it into an impermeable covering that had sufficed to keep the rest of the flour as dry as when it had come from the mill. It was then the month of March, and the divers expected bad weather, which they duly experienced. The equinoctial gales whistled in the rigging of the Racer and snow and wind harassed the salvors. It was possible to work only when the weather abated. At other times they sought the shelter of Lough Swilly and waited for better conditions.

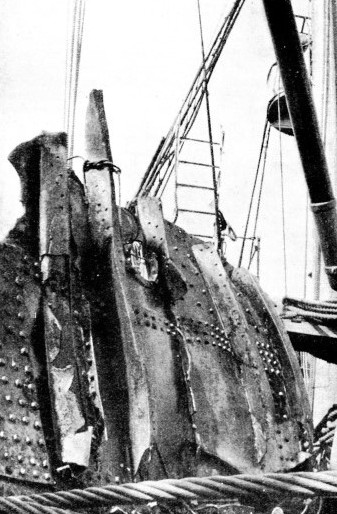

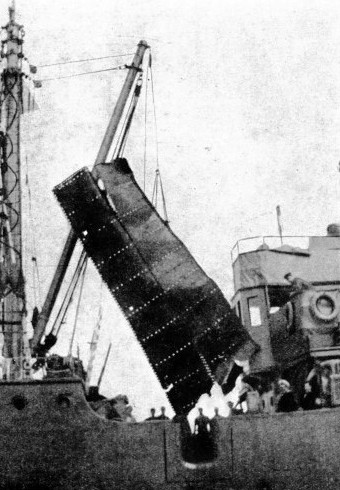

METAL SCRAP. Part of the structure of the Laurentic which was blasted away by the divers and hoisted up on to the salvage vessel. Here it was suspended by cables, as seen here, until it could be conveniently dumped well away from the wreck. Because of the severity of the weather with gales pounding her broken hull, the Laurentic rapidly became a ruin of tangled metal and so multiplied the divers’ problems.

They managed to clear the wreckage until they came to an iron gate, which Diver E. C. Miller, keen to reach the gold, promptly demolished with explosives. Beyond the gate was another mass of displaced cases with which he struggled for two hours, levering and hauling them out of the way until he came to the door of the strong room.

“I’ve got to the strong room, sir”, he reported to Commander Damant.

Only the steel door separated Diver Miller from gold bars worth £5,000,000. He balanced himself in the sloping passage and felt with his fingers for the vulnerable points at which to insert his chisel. With deft blows of the hammer he struck the steel door and was soon in among the cases of gold.

Case on case lay under his feet, hundreds of them, each worth about £8,000. We can well imagine the excitement of Miller and of those on the deck of the Racer. Although they had been so badly hindered by the weather, they had taken only fourteen days to reach the gold. It would have been merely a two-

The cases of gold were quite small, no more than six inches deep and twelve inches square. Judging by their size, all the diver had to do was to tuck one under either arm and walk out with them to send them up to the surface; and to keep on doing this until he reached the last one. Their appearance was, however, deceptive. They weighed about 140 lb. each. It was a big weight for a diver to handle under water in the dark.

Seizing on the nearest case, Miller began to haul and lever it along the passage. The floor of the passage was slippery, as it sloped steeply upward and had a number of turns that were difficult to negotiate. Nor was there room for anyone else to crawl in to give him a hand. The average man would not find it easy to move such a weight on a level floor. It can well be imagined how hard was the task for the diver, with the floor sloping steeply and the case tending to slip back all the time.

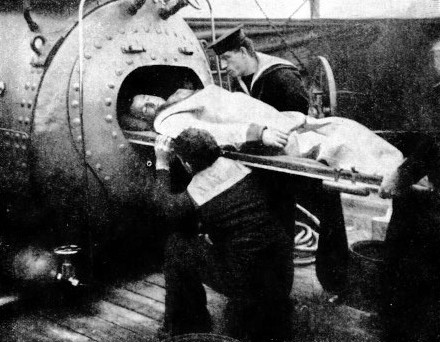

A RECOMPRESSION CHAMBER. Putting a diver suffering from “bends” into the recompression chamber. A diver who had been working for a long time beneath the sea suffered from the effects of breathing compressed air, and if he came to the surface too quickly was liable to get a complaint called the “bends”. The recompression chamber was used to relieve pain by raising the air pressure to that in which the diver had been working. The pressure was then gradually lowered to the normal atmospheric pressure at the sea-

It took every ounce of strength that Miller possessed, as well as all his determination, to remove that first case of gold. He was thoroughly exhausted by the time it was being hauled to the top, Following it up to the 30-

He paid the penalty for recovering that first box of gold by having a painful attack of “bends”, which necessitated his going into the recompression chamber to relieve the pain. The air-

Next day Miller went down the rope and made his way through the passage into the strong room again. Once more he pulled at a box of gold until he had manipulated it through the passage to the entrance.

False Optimism

Resting while it was being hauled to the surface, he went backhand coaxed another £8,000 box of gold up the sloping passage to the entrance port. While he was working in the interior of the ship the wind was beginning to freshen, but he went back and struggled with the third precious box, which he succeeded in sending to the top.

After that he was ordered up by Commander Damant, for the weather conditions were too threatening to allow a longer stay.

The salvors had reason to be pleased with themselves. With £32,000 worth of gold in the cabin of the Racer, it seemed certain that in nine or ten weeks the whole of the £5,000,000 would be back in the hands of the Government. Theirs promised, in spite of the exposed position, to be an easy task.

Meanwhile, with the gale blowing up, Commander Damant cast off his moorings and sought the shelter of Lough Swilly, expecting to be back at his moorings next day and to haul up more gold. The weather ruled otherwise. Increasing in force during the night, the gale raged all the next day and the day after that. Wreckage from the ship began to wash up on the coast. While the gale continued, the wreckage spread until it littered the shore for miles. This was ominous; for as the wreckage was examined it became plain that the gale was tearing the ship to pieces.

For a week the raging gale kept the salvage crew away from the wreck, before they could return to see what had happened. The seas had played havoc with their carefully laid moorings. So, having replaced them, they dropped a line to the opening in the hull and sent down a diver.

When the last box of gold had been sent up, the entrance had been 62 feet below the surface. It was a simple matter for the salvage officer to see the depth at which the diver was working, for the depth was measured by the pressure gauge let into his air pipe. This time, as the diver went down, those on board watched the pointer in the gauge move on past 60 feet, where they had hoped that it would stop, until it marked 103 feet.

This was bad news. It meant that the gale had pounded the wreck so badly that she had collapsed. When the diver found the entrance he could no longer stand upright. Instead he discovered that the decks had folded down until the roof was only eighteen inches from the floor, while what remained of the passage was wedged with plates and girders as though a steam-

All thoughts of an easy job were dissipated. After one taste of the gold to whet their appetites, they found that nothing but hard work would enable them to lay their fingers on the remaining treasure.

Setting steadily to work with explosives, they blew away and hauled out the tangled masses of metal in the collapsed passage, using their charges to blow the deck upward again and inserting shores to keep it from slipping. Foot by foot they forced their way downward until they once more reached the strong room. This was now resting on the sea-

Making his way warily inside, one of the divers began to feel round for the boxes of gold. He could not detect a single box. His feet came to gaps in the floor. “The gold’s not here, sir. It’s gone”, he said over the telephone. “The deck’s full of holes”.

It needed little imagination to guess what had happened. The action of the waves pounding and tearing inside the ship had set the gold sliding with such force that its weight had carried it through the vessel. The question was, how far had it gone and where had it fallen?

To penetrate to the strong room at all the divers were forced to run grave risks. The ship was no longer tied together by rigid members. Girders were bent and plates buckled in the strangest manner. Towering above the divers were the five decks leading to the well of the hold, with the deck supports swept away and the decks liable to fold down at any moment.

Commander Damant shared the risks with the rest, going down from time to time to supervise operations and examine the conditions. Now that the gold had vanished from the strong room, he no longer felt justified in asking the divers to run the danger of those decks shutting down on them.

Judging by the way the ship had collapsed, he calculated the spot where the gold had fallen and instructed the divers to cut a way through the ship from above. Setting their charges, they blew away plates and girders and shackled them to the wires to be hauled to the surface. It was laborious work, for some of the sections handled weighed several tons and all the material had to be heaped up on the ship until it could be taken away and jettisoned where it would not impede operations. At times the Racer resembled a scrap metal yard rather than a ship.

They often had the greatest difficulty in getting the lifting wire down to the diver; for instead of dropping straight it streamed out as if it were a kite in the wind because of the strong current. Even when they were on the bottom the divers were troubled by the force of the waves. When they were examining the ship they were compelled to cling on to the edge of the hull as a roller passed along the surface. They then scrambled a few yards and clung on again while another wave strove to dislodge them from their perch. Their progress was a series of rushes between the waves.

One day a diver working at a depth of 60 feet received a shock as a great block suddenly swished by his helmet at a distance of about a foot. It was attached to a 60-

Nor was the weather the only enemy of the treasure-

All the time the divers were down they were risking their lives, and one or two of them had frightening experiences. For instance, it was customary, in cutting a way down to the gold, to shackle a wire rope to the end of a collapsed plate, haul away from the surface until there was a big strain on the plate, and then slip a charge of explosive as far under the plate as possible and blow it away from its bearings. After this the diver would attach the lifting wire to the piece of wreckage and guide it carefully by the projections until it had a clear run to the surface.

All the time the divers were down they were risking their lives, and one or two of them had frightening experiences. For instance, it was customary, in cutting a way down to the gold, to shackle a wire rope to the end of a collapsed plate, haul away from the surface until there was a big strain on the plate, and then slip a charge of explosive as far under the plate as possible and blow it away from its bearings. After this the diver would attach the lifting wire to the piece of wreckage and guide it carefully by the projections until it had a clear run to the surface.

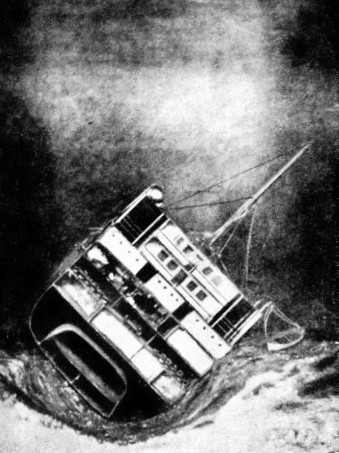

A SECTIONAL DRAWING showing the position in which the Laurentic was found lying on the bed of the sea, 120 feet below the surface. The first diver to descend found it impossible to walk on her deck or along her side. Only by clinging to the rail on the upper side of the vessel could the man work his way along the wreck and investigate the possibilities of salving the lost treasure.

One afternoon Diver Blachford was cutting the wreckage away in this manner. The wire rope from the ship above was straining away at the plate while Blachford took the charge of explosive in his hand, with the intention of crawling as far under the plate as he could to set the explosive at the most vulnerable point.

Calling up to them to give him more air-

Without warning, the shackle holding the plate snapped, letting the plate fall on the back of the diver.

Commander Damant and his men acted instantly. They could not tell what had happened when the shackle snapped, but they realized that it was imperative to get a man down to the spot at once. Luckily, Diver Clear was nearly dressed. Ten or fifteen seconds after the accident the voice of Blachford came up to the commanding officer.

“Give me all the air you can, sir”.

The pressure was at once increased.

“That’s right; give me more yet, and get another diver down here as quickly as possible”.

There was no trace of alarm about Blachford’s voice. Although he was trapped below in an awful position, he remained quite cool. He felt as if the weight would crush him, and he thought that the extra air in his dress might act as a cushion and save his back from being broken.

While the tenders were fitting on the corselet and helmet of Diver Clear, other men were rigging a new lifting wire and slings to raise the obstruction.

“Give me more air”, Blachford kept repeating in a very deliberate voice.

Commander Damant gave him so much air that the roar of it in the diver’s helmet drowned the sound of his voice. The pressure rose until Commander Damant feared it would burst the diving dress. He did not know how Blachford was situated -

Commander Damant was in a quandary. If the dress were intact, an increase in the air might easily burst it and drown the diver. He decided not to take that risk, so he gave the diver as much air as he could without pushing the pressure beyond the limits already reached, and saw Diver Clear, who was now fully dressed, catch up the end of the new lifting wire as he took Blachford’s air-

Coming upon the imprisoned diver, Clear worked fast to fit the slings under the plate.

“Take in the slack”, he ordered those above, watching the wire rope slowly tighten. “Now very carefully”, he warned them over the telephone, as the straining wire began to lift the plate off the recumbent figure.

Directly the pressure on his back had been eased, Blachford was taken to the surface. From the time the shackle had given way until the moment of his rescue was exactly nine minutes. This experience would probably have unnerved most men, but Blachford, accepting it as all in the day’s work, remained quite unruffled.

When Commander Damant was told by Diver Blachford that he had wanted more air to take the weight off his back, the salvage officer mentioned the risk of bursting the dress. “I did not think of that”, remarked Blachford -

Throughout April and May the salvors kept on blasting away at the wreckage and lifting it out of the gap that they were cutting into the ship. The explosions killed countless fish up to 150 yards away; some of the fish rose and floated dead, others sank. Many a time the divers slithered on dead fish lying about the ship, and more than once they were obliged to fix their charges while shoals of dogfish were tearing dead fish to pieces all round. The ferocious dogfish did not seem to suffer at all from the explosions. Commander Damant said that the dog-

The broken furniture and bedding and other objects that remained in the liner had to be disentangled and picked out by hand. As soon as a hopper was filled with this debris, it was hauled to the surface, emptied and lowered again.

It was while clearing this debris out of the way that Miller, who had found the first boxes of gold, now had the luck to trace the gold again; for he came on ten gold bars. He worked so hard getting them out that he suffered another attack of “bends”. After that everybody went at the work with greater energy than ever. Some men had good days, others bad; the biggest amount of gold recovered by one diver in a day during the whole operations amounted to £45,000 -

It was a strange sight to see the men handling gold bars as though they were worth about twopence apiece. But every bar, as it was recovered, was checked off in the list; and from time to time a consignment of gold-

It was a strange sight to see the men handling gold bars as though they were worth about twopence apiece. But every bar, as it was recovered, was checked off in the list; and from time to time a consignment of gold-

ON THE DECK OF THE SALVAGE SHIP. Some of the gold bars retrieved from the Laurentic, lying beside the airpipes upon which the lives of the divers depended. After the first and comparatively-

In spite of the worst the weather could do in smashing up the ship, the luck was with the treasure-

Then the gales suspended operations for the season, and Commander Damant and his divers went off to do work that proved to be even more important than hunting for gold. The salvors were not able to resume until the spring of 1919. Fixing their moorings, they slid down to see what had happened in the interval. They found that the gales had not altered things so much as they had expected. Then they began again with their explosives, shattering and hauling up the steel plates and girders, disentangling the twisted beds and mattresses and timbers from the legs and stuffing of chairs that had adorned the cabins in this part of the ship. This clearing work was a monotonous task that called for lots of patience, but the divers toiled away until the first gold bar of the season was found.

Once they knew they were on the trail of the gold again they were happy. Their finds touched the £100,000 mark and increased to £200,000. The situation they were now working in was rather precarious, for rows of cabins were leaning inward over them and because these supports had been weakened were in danger of collapse.

More than once Commander Damant wondered whether he ought to stop the work to clear the dangerous cabins out of the way. His orders were to recover the gold. The men were steadily bringing it out and he hesitated to waste time on these structures while the gold was coming up. The search was therefore pushed forward, but Commander Damant went down regularly to supervise. At the end of the season the overhanging parts of the ship were still in place, and the gold recovered amounted to £470,000.

The following spring the divers found that they would not have to spend weeks blasting away the overhanging structures, as the seas had hammered them all down. The great gap in which they were previously working had ceased to exist. They could not at first locate anything. Their fixed mark hitherto had been the heel of the mast, but that had shifted about thirty feet. The salvage officers could not tell where to begin again.

They gradually hauled out the plates that had collapsed over the hole, only to find that all the contents of the ship round about had been shot into the gap. It was the most hopeless muddle that could be conceived -

The problem of removing this litter seemed almost insuperable. The salvors brought upon the scene a great grab, such as may be seen picking up huge scoops of coal from a barge, but the awkward position prevented the grab from doing what they hoped. They rigged a giant 12-

Studying the mass of rubbish through the glass of his helmet, Commander Damant concluded that the only way of removing it was to pick it out by hand, dropping each bit of debris into a hopper, so that it could be hauled up. He gave the order, and the divers began their long fight against the sea. Day after day they continued their heartbreaking job, loosening and tugging out the strangest assortment of things imaginable. Whenever they seemed to be making a little progress a gale would rise up and wash more stuff into the hole. All they got to reward them for their season’s work was seven bars of gold.

Studying the mass of rubbish through the glass of his helmet, Commander Damant concluded that the only way of removing it was to pick it out by hand, dropping each bit of debris into a hopper, so that it could be hauled up. He gave the order, and the divers began their long fight against the sea. Day after day they continued their heartbreaking job, loosening and tugging out the strangest assortment of things imaginable. Whenever they seemed to be making a little progress a gale would rise up and wash more stuff into the hole. All they got to reward them for their season’s work was seven bars of gold.

FROM THE DEEP. A massive piece of wreckage torn away from the Laurentic by explosives during the hunt for the lost gold bars. It was the practice to shackle a wire rope to the end of a broken plate and to haul from the surface so as to bend the plate away from the hull as far as possible, then finally to sever it by a charge of explosive. This difficult and dangerous work was undertaken by men of the Royal Navy.

They continued their fight with that tangled mass in 1921, resorting to all the devices they could think of to get rid of it quickly. But the problem of wholesale removal completely baffled them. For a time it really looked as though the British Navy was going to be beaten. To be compelled to haul out rubbish when they expected to recover gold had a depressing effect on the salvage crew. However, as the season progressed a few ingots began to turn up, and Commander Damant put into operation the only scheme for working the wreck that held any promise of success.

The crux of the matter was whether the men could remove the stuff from the crater quicker than the sea filled it. Commander Damant saw that the surest way of recovering the gold was to concentrate all the divers’ energies on removing the rubbish. If they got it out of the way the gold would yield itself up.

To achieve this end Commander Damant devised a method of working that aimed to utilize to the best advantage every minute of the time spent on the bottom. The bare hands, a sack with a scoop tied in the mouth of it and a fire-

The sack of debris and the gold bars had to be placed in the hopper in the remaining five minutes. The relief diver arrived three minutes before the first diver's time was up. The relief gave a hand with the sack, and the first diver was allowed a minute to untie his pipe and line and rise to the 30-

The amount that each diver removed was weighed and marked against his name. This system soon fostered a keen competition among the divers, who toiled with all their energy to beat one another at this new sport of removing rubbish from the sea-

A Terrible Predicament

With no more than forty-

During this period Diver Light had a thrilling experience. Having tied up his air-

The air flowing up in this manner at last made the dress so buoyant that before Light could do anything to stop himself he had floated out backwards. Ho came to a sudden stop head downward about 40 feet from the bottom.

He was quite helpless. His dress was blown out so stiffly by the compressed air that he could move neither arms nor legs. The air-

If water continued to leak into his helmet before anyone could release him, it would not be long before he drowned. The unhappy diver realized this quite well as he telephoned up to tell them what had occurred.

It happened that Blachford, was at the 30-

Light shot up to the top with alarming speed, his dress being so buoyant that the weight of Blachford with his diving equipment -

During 1923 they continued the great treasure-

The next year Commander Damant took the crack divers of the British Navy back to finish the job. Investigating the rubbish on the sea-

Throughout those seven seasons of hard work there was not one accident to life or limb. This is a fine tribute to the care and technical experience of the salvage director.

This great gold-

B ecause of the secrecy with which the work was carried out, the nation was never fully informed of this wonderful feat. As some recompense for the risks they ran, however, the salvors were awarded half-

ecause of the secrecy with which the work was carried out, the nation was never fully informed of this wonderful feat. As some recompense for the risks they ran, however, the salvors were awarded half-

Of the twenty-

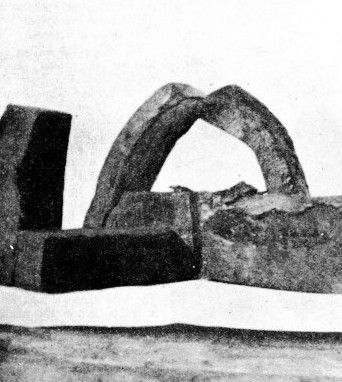

MEN RISKED THEIR LIVES for these apparently insignificant lumps of twisted metal. This photograph shows the amazing manner in which some of the gold bars had been bent by the immense pressure set up by the collapse of the sunken ship’s hull. Gold recovered by 1924, when the authorities decided to conclude operations, was valued at £4,958,708. The cost of the seven-

You can read more on “Diving for £1,000,000”, “Dramas of Salvage” and

“The Shipbreaking Industry” on this website.