© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Naval Intelligence

The extraordinary success of the Naval Intelligence Division of the British Admiralty during the war of 1914-

WHEN the phrase “intelligence work” is used to describe the acquisition of foreign military secrets, it is assumed by many to be merely a polite euphemism for spying. That assumption, however, is not altogether justified. Some of the most valuable intelligence work in war and in peace has been accomplished by methods which bear no relation to the ordinary practices of espionage.

The amazingly detailed knowledge of German naval movements obtained by the British Admiralty during the greater part of the war of 1914-

For this reason every Power, great or small, keeps a close watch on the militant activities of neighbouring states and, if only as a measure of self-

Since uncertainty and suspicion are the parents of fear, a thoroughly efficient intelligence service is in some degree a safeguard against panic and all its evil consequences. Wise statesmen realize the dangers inherent in secret armaments, and therefore strive by means of international agreements to ensure that the great Powers shall communicate to one another the extent of their respective armament programmes.

Hitherto these efforts have been only partly successful, but one of the outstanding achievements of the London Naval Conference of 1936 was the drafting of a treaty which binds the signatory Powers to exchange advance information about the number of new warships they are proposing to build and the tonnage, gun-

Hitherto these efforts have been only partly successful, but one of the outstanding achievements of the London Naval Conference of 1936 was the drafting of a treaty which binds the signatory Powers to exchange advance information about the number of new warships they are proposing to build and the tonnage, gun-

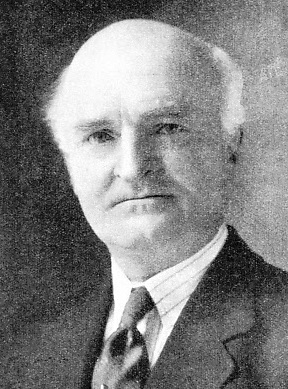

ADMIRAL SIR WILLIAM REGINALD HALL was Director of the Intelligence Division of the Admiralty War Staff during the war of 1914-

This important treaty was signed by Great Britain and the Dominions, the United States and Franco, and it is hoped that all the other important naval Powers may eventually adhere to the agreement. Such a universal compact, by entirely removing the element of secrecy from naval armaments, would unquestionably tend to banish one of the most potent causes of international friction and ill-

By common consent, the most comprehensive and efficient intelligence service known to history was that built up by the British Admiralty in 1914-

It is commonly believed that most, if not all, of the naval actions of the war were the result of accidental encounters between the contending fleets. The truth is, however, that every big naval engagement in the North Sea was the direct consequence of dispositions ordered by the British Admiralty on the basis of intelligence reports. The battle of Heligoland Bight on August 28, 1914, is the earliest and most elementary example of this process of cause and effect.

During the preceding weeks British submarines, which had been scouting in the Bight, had taken careful note of the system by which the Germans maintained their defensive patrol in those waters. The Admiralty knew, therefore, the approximate strength of the German forces in a given area at a given time, and this information, furnished by British submarines, and supplemented by intercepted radio signals from the German Naval Command, enabled the Admiralty to determine not only the position of the enemy’s main fleet, but also the time it would take that body to reach the outer waters of the Bight.

With this knowledge in hand it was comparatively simple to draw up a time-

Broadly speaking, the plan worked admirably, though defective staff work caused some confusion and nearly led to unfortunate incidents. Even in those early days, when the British intelligence system was still in a rudimentary form, the superiority of its information over that of the enemy gave Great Britain an immense and invaluable advantage.

At a later date, when the naval intelligence had been brought to a high state of perfection, a German commentator remarked: “The British Admiralty seems to get wind of every plan we make as soon as it is made. We cannot move a ship from one port to another without their hearing of it almost as soon as the order is given. We, in short, are working in the dark; they in the full light of day.”

Those words contained little exaggeration of the situation during the last two years of the war. In January 1915 occurred the battle of the Dogger Bank, which had been deliberately staged by the Admiralty on the strength of its intelligence reports. This fact has been revealed by Mr. Winston Churchill, who was then First Lord of the Admiralty. He describes how he was sitting in his room at the Admiralty on the morning of January 23, when Admirals Sir Arthur Wilson and Sir Henry Oliver entered unannounced, obviously charged with portentous news.

“First Lord, those fellows are coming out again.”

“When?”

“To-

Mr. Churchill then recounts the various telegrams of instruction which were at once dispatched to the Fleet and continues: “This done, Sir Arthur Wilson explained briefly the conclusions which he had formed from the intercepted German message, which our cryptographers had translated, and from other intelligence of which he was a master.”

So it happened that when the German battle cruisers reached the Dogger Bank, believing their presence to be entirely unsuspected, they found Beatty awaiting them in superior force.

The battle of Jutland came about in much the same way. On May 30, 1916, the intelligence officers informed the Admiralty that the German Fleet or part of it was preparing to put to sea early on the following morning and would probably make for a position in the North Sea which they were able to indicate.

Accordingly, the Admiralty instructed Admirals Jellicoe and Beatty to leave their respective bases at Scapa, in the Orkneys, and Rosyth, in the Firth of Forth, and to effect a junction during the following afternoon in approximately the position for which the German Fleet was believed to be heading.

As events fell out the opposing fleets would have missed one another by a narrow margin had not some German destroyers stopped to examine a neutral merchantman. This, however, does not alter the fact that the Admiralty, thanks to its incomparable intelligence service, knew beforehand that strong enemy forces were putting to sea and was therefore able to take steps to intercept them.

Intelligence Officers Misled

This was one of the extremely rare occasions on which the German Naval Command was able to mislead the wide-

Had it been known or even suspected that the German battle cruisers were being closely supported by their main body, there is no doubt that the wide gap between Jellicoe’s battleships and Beatty’s battle cruisers would have been considerably lessened, and that the main action of Jutland would have been fought several hours earlier and possibly with more decisive results.

The two factors mainly responsible for the brilliant success of British naval intelligence work in 1914-

THE POSITION OF ENEMY WARSHIPS during the war of 1914-

These wireless conversations were invariably carried on in code, and latterly the code was frequently changed, sometimes every twenty-

During the earlier stages of the war the German naval code was an open book to British naval intelligence officers. This was due to the recovery of a secret code-

Even when new codes were adopted the intelligence officers were sometimes fortunate enough to salve a copy of the latest edition from a sunken U-

As soon as it was found that German naval shore stations were freely communicating with one another and with ships at sea by means of radio, the British Admiralty established directional wireless stations all round the coast to pick up these messages and to determine their source. The method employed was comparatively simple.

Say, for example, a German submarine off Beachy Head called up a consort with whom she had a rendezvous. The call would be picked up by three or more of the coastal listening stations, each of which would report to the nearest Base Intelligence Office the message it had heard and the direc tion from which it came. By taking cross-

Eventually this system of locating enemy submarines from their own wireless signals became so highly developed that at any given time the Admiralty knew exactly how many U-

This information was of immense value, since it enabled the Admiralty not only to maintain a constant offensive against the undersea raiders, but also to give timely warning to shipping of areas to be avoided. It is no exaggeration to say that millions of tons of shipping were saved and that the submarine menace was finally defeated largely, if not mainly, because of this wonderful system of marine intelligence. To the same agency was due in great part the high rate of mortality prevailing among enemy submarines in the last two years of the war.

It was often possible for the intelligence officers to follow the course of a German U-

Every trade has its tricks, and naval intelligence is no exception to the rule. Before and during the war of 1914-

naval Power spent a great deal of time and trouble in camouflaging its new construction. Spurious plans of new warships were prepared and palmed off on foreign secret agents, charts of non-

A Confidential “Navy List”

While an efficient intelligence service is indispensable as a means of noting the warlike preparations of foreign countries, an enormous amount of time and money is wasted by intelligence departments in compiling information which is not only useless but also dangerously misleading.

A notorious example of this, for instance, was the famous system of compiling dossiers of all the senior officers of foreign navies, the idea being that such biographical notices enabled the actions and reactions of any officer in the face of given circumstances to be more or less accurately predicted. Unfortunately, those who compiled these dossiers almost invariably omitted some vital characteristic which supplied the key to the temperament of the individual concerned, so that when unusual circumstances did arise the subject more often than not acted in a manner diametrically opposed to the forecast based on his dossier.

F urthermore, it was a standing joke in the French and British intelligence circles during the war of 1914-

urthermore, it was a standing joke in the French and British intelligence circles during the war of 1914-

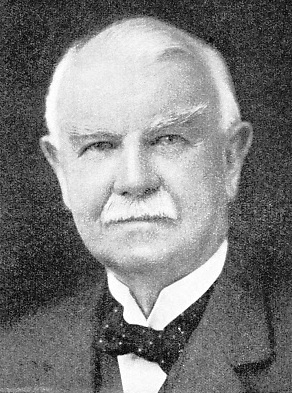

THE LATE SIR JAMES ALFRED EWING, KCB, presided over the cryptographic staff of the Naval intelligence Division for some time during the war of 1914-

Although the British Naval Intelligence Service developed in 1914-

One has only to compare the welter of radio signals, many of them superfluous and wholly irrelevant, made by the Grand Fleet during the Jutland battle with the exiguous and terse signals registered when the same Fleet put to sea a year later, to realize that British naval leaders had taken to heart the precept that “silence is golden.”

The justification for all intelligence work was neatly summed up by Napoleon I when he said that the issue of battles and the fate of empires would be determined “if one could only see what is happening on the other side of the hill.” Certain naval and military secrets will always exist, but it is open to doubt whether the money and personal effort expended on intelligence work in time of peace is entirely justified.

You can read more on “Battle of the Falklands”, “Modern Ocean Raiders” and “The Navy Goes to Work” on this website.