© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Modern Ocean Raiders

The exploits of armed German merchantmen and certain independent cruisers such as the Dresden during the war of 1914-

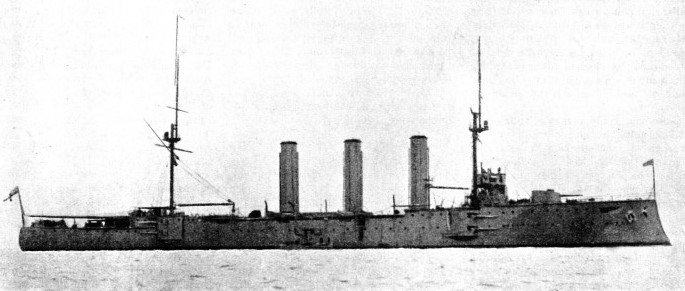

A CRUISER OF 9,800 TONS DISPLACEMENT, built in 1903, H.M.S. Kent had a designed speed of 23 knots. She was largely responsible for the destruction of the Dresden in 1915. The Kent had a length of 440 feet, a beam of 66 feet and a mean draught of 24 ft. 6 in. Her armament consisted of fourteen 6-

AN island nation such as Great Britain, dependent for its trade, its raw materials, and largely for

its food, on shipping arriving from overseas, at once offers to an enemy, on the outbreak of hostilities, long routes of exceedingly vulnerable traffic. The sea lanes, for example, extending from South America to the English Channel, could not help being given primary attention during the war of 1914-

The chilled meat trade from the Argentine had reached immense proportions, and, if it had been cut off, millions of British people would have been left short of meat. Where homeward-

In addition there was a large and valuable exchange of goods always going on between the British Isles and North America, and between the West Indies and the British Isles. A tempting bait was also offered by the rich trade which came up from India, Australasia and the Orient through the Red Sea and the Suez Canal, the Mediterranean and the Bay of Biscay into British waters.

The Germans, on the outbreak of war, with their keen perception and preparedness, were not slow to appreciate where lay Great Britain’s vulnerability, their own weakness and their own special opportunities. Thus they soon sent the light cruiser Emden to operate in the Indian Ocean and cause great anxiety, until she was finally sunk by a British cruiser. The Konigsberg likewise had a brief period of molesting off the East African coast until things got too dangerous for her and she hid herself up the River Rufiji (in Tanganyika), never again to emerge.

In the area covered by the North and South Atlantic there took place not merely a clever campaign, but also a series of incidents replete with thrilling adventures. The narrow escapes, the surprising coincidences, the varying phases, the employment of wireless and the use of modern steel ships, all combine to make this story far more entertaining than any work of fiction.

By August 1914 Germany had in seventy years built up such a Mercantile Marine that it was second only to the British. Controlled by ten powerful steamship companies such as the Hamburg-

The outbreak of war hurried the German liners into neutral ports, where they were mostly interned for the next four years and rendered useless through fear of the Royal Navy. The British nation, however, still owned the world’s largest fleet of mobile moderate-

Seeing that the Grand Fleet dominated the High Seas Fleet, Germany’s primary hope was to send out armed steamers stealthily, escape (if possible) attention off the North of Scotland, and then try extensive raiding in those areas where the few remaining British passenger liners and the majority of the smaller steamers might be expected to be discovered. In the olden days of sail, so long as a ship had fresh water, salt beef and biscuits, she was independent of the shore and could roam the seas for three or four years, varied by an occasional stoppage at the back of some lonely island or secluded bay, where her foul hull could be cleaned after careening. But a modern steamship is far less independent, and is entirely at the mercy of her fuel.

Moreover, there comes a time when boilers must be cleaned and engines overhauled, necessitating repairs that demand the facilities of a dockyard. If, too, she is a fast steamer, then every few days she must replenish fuel, and this means that colliers must meet her on a given date at a particular rendezvous. How, amid the risks of war and the uncertainties of events, can this be guaranteed? If the raider is running short of fuel, how can she avoid being herself captured when some smart grey naval unit comes rushing towards her?

It was the Emden which sought to overcome this difficulty by capturing every collier she met, putting a prize crew on board, and ordering the colliers to wait in some assigned locality. Other raiders copied that idea with considerable success, and even robbed vessels carrying general cargo; but the game could not be easy, and was influenced by geographical conditions. To empty a steamer alongside her in the open sea and damage both hulls, as the ocean swell rendered fend-

Secret Rendezvous

The Germans, however, fared well, largely because of their forethought. Six years before the war they had issued instructions to their liner captains as to what would be their duties should hostilities break out; a “Cruiser Handbook” had been compiled, giving a list of secret rendezvous whither liners could make and be fitted with guns. One such spot was near the Bahamas and another was off the lonely South Atlantic island of Trinidad, east of Brazil. It was here that the Cap Trafalgar bunkered during the first weeks of the war, and here that the Hamburg-

By means of wireless and telegraph cables this remarkable chain maintained an unbroken connexion with Berlin through New York. Even such spots as Lome, in Togoland, Tenerife, in the Canaries, and Horta, in the Azores, were not too remote for the organization. Each supply officer had to ensure that the requisite number of colliers could be found in his area, so that any raider had only to look into the “Cruiser Handbook”, select her rendezvous, arrive, and go alongside for bunkering without unnecessary wirelessing. At the head of this extensive organization, and Controller-

Thoroughness was the characteristic of this Atlantic system, and the details of one section will suffice as an instance. Korvetten-

During the first week of war German colliers with coal from Cardiff and Barry managed to reach Las Palmas. The Hamburg-

FORMERLY AN ATLANTIC RECORD-

This company had contracted to provide 75,000 tons of coal for German cruisers every month, but this arrangement collapsed because not enough colliers were available afloat, credit could not be granted, and the United States Government began to show a firm hand. All the same, Boy-

The first German armed merchant cruiser to rush the Narrow Seas was the North German Lloyd Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse. This four-

“I Will Sink You!”

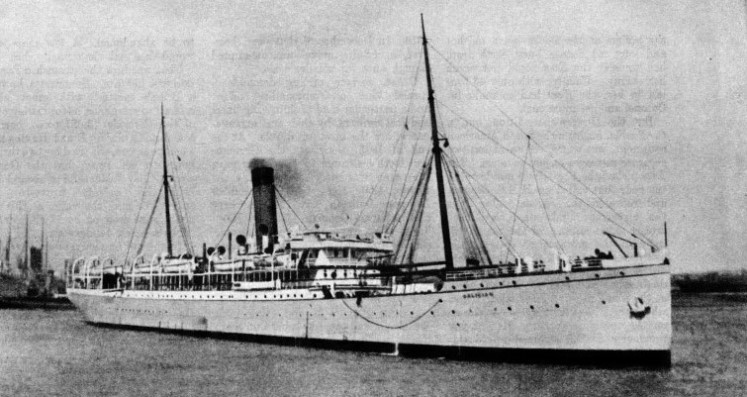

“Is the track clear?” he heard the Galician calling.

The German raider wirelessed back an encouraging message, and at 2.45 p.m. the two liners met.

“If you communicate by wireless, I will sink you”, Captain Reymann abruptly ordered. But for the reason that the Galician carried 250 passengers, who would be an embarrassment and soon eat up the German provisions, the raider next morning at five o’clock allowed her to proceed. Two hours later Reymann stopped the British steamship Kaipara, 7,392 tons, homeward-

The Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse had been built for the purpose of making quick passages between Germany and New York. She was most extravagant with coal, and consumed 250 tons a day even at half-

The Duala had defied the Spanish authorities at Las Palmas by staying forty-

A SECOND-

Thus amply supported by the secret organization, the raider looked forward to further successes with replenished bunkers. She was still taking in coal on August 26 when into the anchorage there suddenly steamed H.M.S. Highflyer, a 5,600-

The Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse had a short yet effective career in her new role. She had destroyed about £400,000 worth of British shipping, but the enforced delay caused by waiting for coal had been fatal and had enabled the Highflyer to learn of her whereabouts. Moreover, apart from her being greedy for fuel, the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse was not the right type for raiding. Her very appearance, with that characteristic German gap between the second and third funnels, would eventually have betrayed her. Still, it needed more months before Germany was to realize that the most ordinary, medium-

Meanwhile the Atlantic trade routes became increasingly perilous to merchantmen. Since no more vessels, naval or mercantile, dared just now to come out of German ports, Germany could have recourse only to those of her regular cruisers belonging to the China or West Indies stations, or to any liners which happened to be in foreign waters and could escape internment.

One of these cruisers was the Dresden, sister ship to the Emden, six years old, armed with ten 4-

Coaling in Mid-

She turned south, cruised along the shipping track that led to Europe from South American ports, and on August 6 off Para stopped the British steamer Drumcliffe from Buenos Aires. When it was found that the steamer was in ballast, needed fuel, and that the master had brought with him his wife and child, the German captain let the ship go, after having destroyed the wireless and pledged master as well as crew not to take part in war against Germany.

An hour later came the steamship Lynton Grange, bound for Barbados. She shared a similar experience, but in the meantime the Hostilius was also stopped and her people all refused to sign the declaration of inactivity. Even so, considering this 3,325-

After having cruised athwart the shipping tracks the Dresden ran short of coal and wirelessed the steamship Corrientes, which had been waiting in Maranhao. The two met in the afternoon of August 8, and the Dresden took the Corrientes into the little-

At first she was not successful, and again the fuel problem had to be faced. Fortunately the supply system worked well, and the Hamburg-

The Corrientes was sent back into Pernambuco, but presently two more supply steamers, the Prussia and the Persia, came out, so the Dresden was being well looked after. On August 15 she sank the Hyades, 3,352 tons, carrying a cargo of grain. The prisoners were put on board the Prussia and were landed at Rio Janeiro. The Dresden then made for Trinidad Island with the Baden. Here assembled the small German gunboat Eber, which had escaped from Capetown, the German steamship Sleiermark from German South-

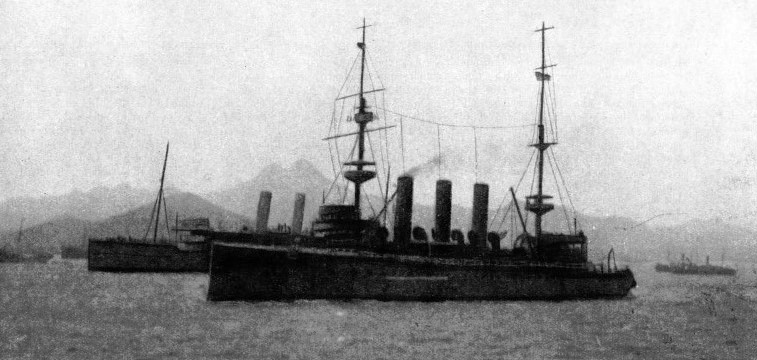

DISCOVERED AT A LONELY PACIFIC ISLAND after having escaped detection tor more than three months, the German cruiser Dresden flew the white flag at her foremast in surrender. She was caught on March 14, 1915, at the island of Juan Fernandez, having escaped destruction at the battle of the Falklands. She stood high out of the water because she was extremely light, due to her empty bunkers. Her normal draught was 17 ft. 9 in.

Having replenished with food and fuel, the Dresden was off again southwards with the Santa Isabel and the Baden as tenders. On August 26 she sank the Holmwood, which was carrying Welsh coal from Newport (Mon.) for Bahia Blanca. Her crew was transferred to the Baden.

Captain Ludecke was now bound round Cape Horn into the Pacific to meet at a later date Admiral von Spee coming eastwards from China waters. As the Dresden was then approaching cold latitudes, and her machinery had not been given an overdue refit, Ludecke sent the Santa Isabel ahead to procure warm clothing and materials necessary for engine repairs.

This tender reached Punta Arenas, in the Magellan Straits, on September 4, whence she telegraphed the supply centres at Buenos Aires and Valparaiso, cabled the German Admiralty at Berlin, and acted as wireless link with the Dresden, which temporarily hid herself in Orange Bay, Hoste Island, by Cape Horn. So rarely do vessels of any sort touch at this inhospitable spot that mariners by long custom “leave their card” here, writing on a board their ship’s name and the date. Thus when the Dresden’s storm-

A Lone Fugitive

Having left this windswept anchorage on September 16, with the Baden, the Dresden two days later chased the Pacific Steam Navigation Company’s liner Ortega, bound for England from Valparaiso. Captain D. R. Kinneir, rather than surrender to a 24-

The Dresden, having feared to follow, proceeded up the Pacific, coaled from the Baden in St. Quentin Bay (Gulf of Penas), reached the lonely island of Mas-

Having barely survived the Falklands defeat at the hands of the British squadron, the Dresden needed coal, but her wireless calls for a supply ship received no reply. On December 10 she entered the tricky Cockburn Channel and came to anchor at 4 p.m. in Sholl Bay, some sixty miles south of Punta Arenas.

This Magellanic area would not be too healthy, with perhaps one or two British cruisers searching for her in the district, but Ludecke was in a dilemma. He came in, so to speak, by the back door. He hoped to find at least one of the supply ships at Punta Arenas, and meanwhile he had only 160 tons of fuel in his bunkers. So desperate had his condition become after fast steaming that at Sholl Bay he sent his men ashore to cut down trees, but this timber was so rain-

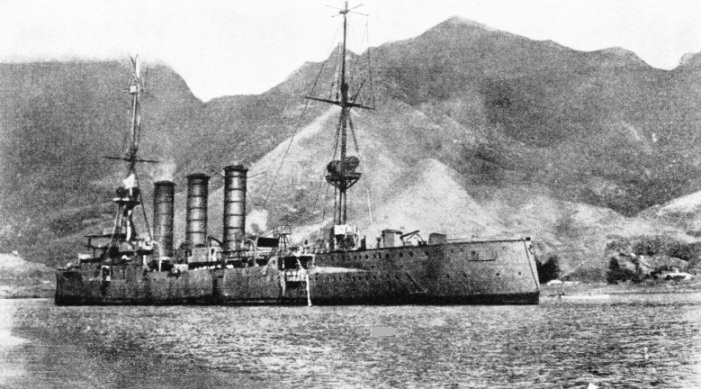

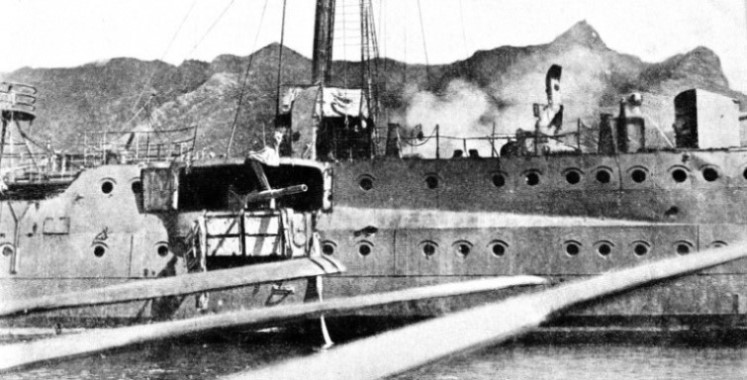

WITH GUNS STILL TRAINED ON THE ENEMY, the Dresden was abandoned by her crew at Juan Fernandez, where she was cornered by H.M.S. Kent, H.M.S. Glasgow and the Orama. This photograph was taken from one of the boats sent to take possession of her, but the Dresden was on fire aft and finally sank.

Along came the Chilean torpedo-

Luckily for Ludecke, however, the German Roland liner Turpin had been at Punta Arenas ever since hostilities had broken out, and she allowed the Dresden 750 tons of briquettes, which were transferred by the evening of December 13. At 10 p.m. the German cruiser steamed away down the Straits under cover of darkness, but five hours later there reached Punta Arenas the British cruiser Bristol.

From now onwards the Dresden led an exciting life comparable only with that of some delinquent “on the run”. Hunted incessantly, she hid herself in different parts of the Magellan Straits, where there is a bewildering labyrinth of channels and islands, and even the British Admiralty charts were far from accurate because of inadequate surveys.

The environment here was reminiscent of Norway, though far more fierce in its primitiveness. Valleys, wild gorges, snow-

The German consul at Punta Arenas tried to persuade Ludecke to intern the Dresden, but he declined and, having picked his way cautiously through Magdalena Sound, Cockburn Channel and

many rock-

British cruisers continued to comb this channel and that, exploring bays and fjords; but their work was rendered incomplete because of the charts. In important places where the sheet indicated land this was water. The Germans, however, obtained invaluable local knowledge, chiefly through their efficient Consul at Punta Arenas and through German subjects who had in preceding years settled down thereabouts as sheep-

Identity Discovered

Outstanding among the trappers was Albert Pagels, who had once served with his nationals in the Boxer rebellion. Pagels was a genius at overcoming obstacles and an ardent patriot of the Fatherland. In his little 26-

On December 20, Ludecke sent the Amasis to Punta Arenas, hoping that the Minnesotan’s coal would be transferred, but the Chilean authorities forbade the transference and detained the Amasis. There arrived, however, at Punta Arenas the Hamburg-

When next Pagels visited Ludecke, it was to learn that on this same December 26 a motor sailing-

“Why, you’re Germans!” remarked the French hunter.

“No, we’re not.”

“Yes, you are. Look at the tattooing on your arms.”

That gave the Dresden’s nationality away. The British cruisers would soon discover the hiding-

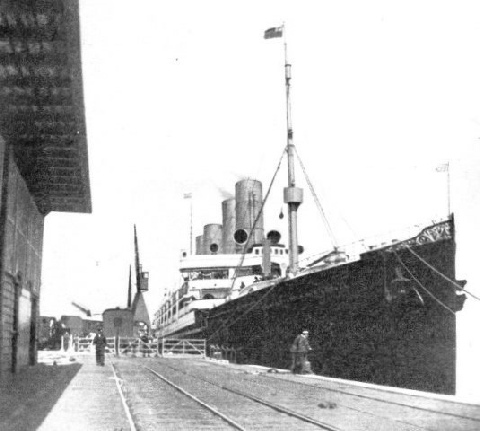

HELD UP BY AN OCEAN RAIDER, the Galician was later allowed to proceed to Southampton because she had 253 passengers who would have been an encumbrance to the raiding vessel, the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse. Built in 1900, the Galician, 6,762 tons gross, was 440 ft. 4 in. long, 52 feet in beam and 27 ft. 7 in. in depth. Her name was later altered to Glenart Castle, and when serving as a hospital ship she was sunk by an enemy submarine in the Bristol Channel on February 26, 1918.

Meanwhile, by the daring pilotage of Pagels, the big supply steamer Sierra Cordoba was brought from Martinez Inlet at night and joined the Dresden on January 19. On January 28, the Dresden was again found out by an otter-

But Ludecke, while conscious that further delay would ensure his capture, preferred the Pacific. By zig-

Next hastened the climax. It was that modern need for fuel which caused the trouble. Ludecke sent the Sierra Cordoba into Valparaiso, where she arrived on March 3 and was allowed to get away with 1,200 tons of coal four days later. But the Dresden was not meeting with the prizes she expected, her coal was running short and the Sierra Cordoba had not yet returned.

A Thrilling Chase

Among all the false rumours, one invaluable bit of information reached the British Navy. An intercepted message stated that the German collier Gotha, which had left Montevideo on the night of February 20, was to make a rendezvous about 200 miles south of Mas-

It was already March 5, and H.M.S. Kent (Captain J. D. Allen) was still seeking the Dresden among the narrow, twisting waterways near the Magellanic Barbara Channel. As soon as it was light enough, the Kent put to sea, worked up to 16 knots, and an hour before dawn on March 7, reached the rendezvous. To the crew’s intense disappointment not another ship was in sight, and the Kent herself had now only 575 tons of coal left.

Captain, later Vice-

“Full speed ahead!” The order was given and the Kent altered course so as to head her off. The Kent was undoubtedly closing on the Dresden, when suddenly she turned away till she was stern on to the British vessel. The Dresden was so light out of the water that she was undoubtedly in great need of fuel, but the Kent made the enemy consume coal still more seriously as the chase became fast and furious. Spars and spare bits of wood were thrown into the Kent’s furnaces, canvas screens were removed to lessen windage, and the stokers managed to get 26,000 horse-

But the Dresden’s condition, out in the Pacific, far from the South American continent, was worse. She sent out two separate messages on her wireless. The Kent picked these up, could not decipher the code, but called up H.M.S. Glasgow and repeated the signals. For days the cleverest minds on board that cruiser made nothing of the puzzle till early in the morning of March 13 a lieutenant elucidated it. These were orders for some unknown ship — undoubtedly a collier — to meet the Dresden at the island of Juan Fernandez. Thus, when the Glasgow, Kent and Orama on the morning of March 14, having previously coaled, steamed up to this Robinson Crusoe’s island, they had the Dresden at their mercy.

Thinking she was about to escape, all three fired on her for five minutes. Then the German hoisted a white flag, the crew began rowing or swimming to the shore, the ship, on fire aft, began to sink and finally disappeared bows first into the water. That was the end of an exciting career, the finish of a dangerous raider which had given British cruisers endless trouble.

Thanks to the persistence of British patrolling cruisers, and the ultimate breakdown of Germany’s supply system, the enemy’s Atlantic raiders had shot their bolt long before the end of 1915. In December of that year, however, a certain revival was attempted though on a far smaller scale.

Ocean surface raiding demands a special kind of commanding officer and a particular kind of ship. Big liners and fast cruisers, by their fuel extravagance, are the most unsuitable. At the end of 1915, therefore, the Germans sent forth a steamer to which they gave the name Moewe. She was really the Pugno, 4,500 tons, with a speed of 14 knots, built in May 1914 to carry bananas from German Africa to Hamburg. This was a much more suitable, single-

Fourteen Ships Captured by One Raider

Armed with 4.1-

The Moewe then cruised about the Atlantic, where this single-

That was how the steamship Farringford met her fate. Sometimes, however a British master, with great pluck, refused to surrender, as for instance that of the Corbridge (3,687 tons), carrying coal from Cardiff for Brazil. Having made a smoke screen, she tried for two thrilling hours to get away, but the German was slightly faster and a second shell made the Corbridge heave-

In spite of narrow escapes, the Moewe got back to Germany by the north-

Neither the Moewe nor her captain tried the game again, although others did, sometimes with failure, sometimes with success. The ex-

ONE OF THE MANY VESSELS STOPPED by the German cruiser Dresden and later released was the Lynton Grange. On August 6, 1914, she met the German raider off the Brazilian coast. A vessel of 4,252 tons gross, the Lynton Grange was built in 1912 at Newcastle-

You can read more on “Battle of the Falklands”, “German Shipping” and “Trap Ships of the Fishing Fleet” on this website.