© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

“Trap Ships” of the Fishing Fleet

Of all the heroic adventures that occurred with mystery ships during the war of 1914-

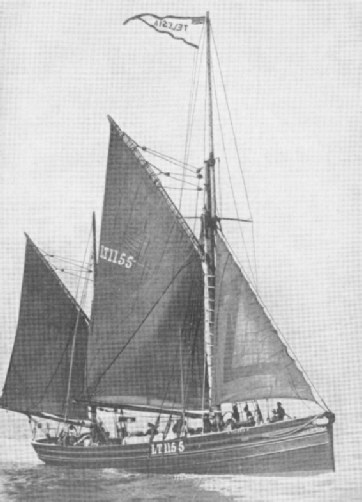

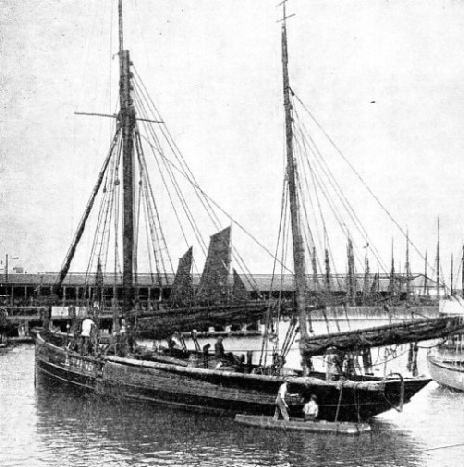

THE LOWESTOFT FISHING SMACK TELESIA was one of the plucky little craft that went to their fishing grounds during the war of 1914-

IF anyone in August 1914 had dared to suggest that sailing warships would in a few months’ time again be used to fight under the White Ensign, he would have been ridiculed as an irresponsible prophet After several generations of steam and steel how could the Royal Navy revert to vessels propelled by the wind?

In the chapter “Salute to a Hero” we saw that the U-

There were many difficulties, however. For example, it was hard to find officers and men accustomed to canvas, for the almost universal reliance on machinery had driven most of our real sailors off the seas. Moreover, it seemed suicidal for any wooden ketch or schooner to entice deliberately such a mobile and evasive mechanical marvel as the submarine. With the fickleness of winds and the problem of tides how could the slow, old-

But the answer will be found in this chapter. Some of the pluckiest duels were fought by the weakest little ships in the most unfavourable conditions. It is well that real life should afford scenes of gallantry more thrilling than any novelist would dare to present.

The sailing “trap-

A popular ground for trawling was from twenty to sixty miles southeast of Lowestoft, and this the Germans soon discovered during the summer of 1915, when they began sending over from Flanders to the East Anglian coast that new class of submarines known as the UB type. These vessels were about 90 feet long, 10 feet beam and 9 ft. 9 in. draught, with a surface speed of 6½ knots and a submerged speed of 5 knots. They carried two torpedoes and eight mines, and a small gun was mounted close to the conning-

The Lowestoft smack skipper has his own navigational methods His knowledge of the local depths and of the nature of the sea-

No finer or hardier type of sailorman is to be found anywhere. Rugged, direct of manner, they collectively illustrate the “brotherhood of the sea”. Often enough the smack’s crew will all be relatives — father, sons and sons-

Then on June 3, 1915, began the first of many losses, when the smack E. & C. was captured by a German submarine forty miles from the land and sunk by a bomb. On the same day, but ten miles farther out, the Boy Horace was destroyed in a similar manner. A third smack, the Economy, was sunk on June 4. So the losses of Lowestoft ketches went on till the end of September, only to begin again the following January.

It was to counteract these attacks on the fishing fleet that in August 1915 four Lowestoft smacks were commissioned as decoys, each armed with a concealed three-

On March 23, 1916, the armed smack Telesia was about thirty-

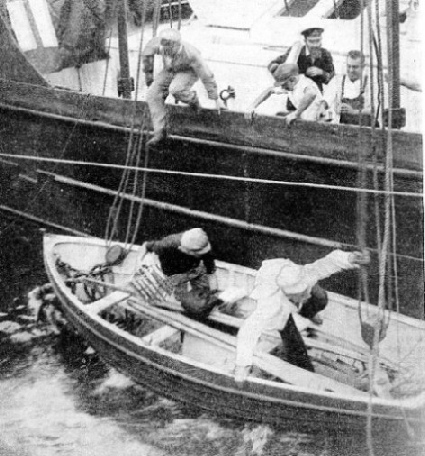

THE PANIC PARTY was one of the most important factors contributing to the success of the larger Q-

Nothing further happened till 1.30 p.m., when the visitor approached the Telesia, made a careful preliminary scrutiny, satisfied herself that here was a ready victim and got within fifty yards of the smack’s starboard bow. She. then submerged, but kept her periscope just visible. Evidently the commanding officer was still undecided and nervous, for he presently went away, came back an hour later to have another look and disappeared once more. But at 4.30 p.m. he returned from the north-

If he feared the risk of going alongside, capturing and then destroying the Telesia with the usual bomb, at least he could have opened fire with his gun while on the surface. But the strange visitor preferred to remain almost invisible some 300 yards away and fire a torpedo. Such a missile costs hundreds of pounds, and to use this weapon against a 50-

We can well imagine the feelings of the Telesia’s people as they saw this steel fish rushing towards their wooden hull. Skipper Wharton at once threw off all disguise, brought his three-

This time the German approached from the starboard quarter, and fired a second torpedo which seemed as if surely destined to hit. Luckily this also missed, passing forty feet astern. At a distance of only seventy-

These were enough for the German, for the third shot would have been fatal. Preferring to break off the engagement, the enemy made a crash dive — so hurriedly that the vessel went down steeply by the bows and revealed her propeller — and thought it wiser to make across the North Sea for Flanders.

This engagement was not without its lesson to the Lowestoft naval base. The fickle wind died away, and the Telesia’s sails flapped idly in the swell. She would have been immobile had the enemy returned. It was now decided that these decoy smacks should be fitted with internal combustion motors, to give them at least a sporting chance. But Skipper Wharton, with his crew of three fishermen and four active service men (a naval chief petty officer, a leading seaman, an A.B. and a marine) had done so well that Wharton was awarded a D.S.C. and two of his shipmates were given the D.S.M.

A month later, on April 23, the Telesia again had come out of Lowestoft decoying; but on this occasion she had changed her name to Hobbyhawk and was commanded by Lieut. H. W. Harvey, R.N.V.R. With her now operated a similar smack named the Cheero, commanded by Lieut. W. F. Scott, R.N.R. An ingenious idea was to be attempted. Instead of towing the genuine trawl, either vessel was to drag through the water 600 yards of special nets attached to mines that would explode as soon as the nets became fouled by an object. Experiments had proved that, even with this length astern, a smack could still make progress at 3 knots and she would appear exactly as if she were trawling.

Caught in the Nets

The scene off the East Anglian coast that afternoon was some ten miles north-

For some months past clever scientific minds on the Firth of Forth had been making a series of trials, to evolve some instrument which could be lowered into the sea as a listening device. If the elusive submarine could not be seen, perhaps she might be located by sounds through a hydrophone. The screw revolutions of a submarine under electric or oil motor power make noises characteristically different from the “thump-

The wind had again fallen light, and the Cheero was heading away to the south-

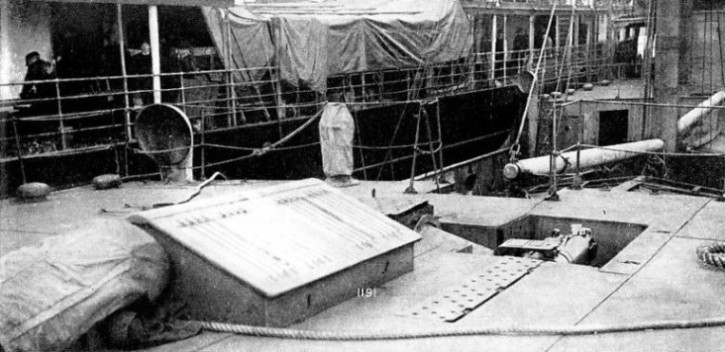

COMMISSIONED AS A DECOY in August 1915, the Lowestoft smack Telesia was armed with a concealed three-

They waited and watched, eyes fixed on the wire towing the nets. It was bearing a tremendous strain just now; then it eased up, as if relieved of heavy weight. Next it became suddenly tight again, followed by a terrific explosion in the nets, the water being thrown twenty feet into the air. A slight pause, and a second upheaval came out of the sea, followed by oil. Every man on board the Cheero remained at action stations, prepared for the next development, but it was obvious what had happened.

The hydrophone confirmed what eyes had witnessed, for the sound of this visitor’s motors had ceased, never to be heard again. Another brief interlude, and the hands were ordered to haul nets, but this was no easy operation. Ordinarily the job could be done by two men, but such was the dead weight this evening that it needed half-

Fragments of steel were seen in the nets, and one piece was brought on board. The men went on pulling, but as the third net came along another surprise occurred. Heaviness vanished and all strain had gone. Everyone noticed a strong smell of oil. Further examination revealed that one of the net-

On reaching Lowestoft Harbour these nets were subjected to further examination, when more bits of steel — some of quite large size — fell out. These fragments were all that remained of UC-

The first explosion was followed by UC-

These boats from Flanders used to carry a dozen mines each trip, so that they always were a menace to themselves until the last black, horned “egg” had been deposited. But the contest between these submarines and fishing craft went on till the end, with alternate victories and losses. Two days after the Cheero incident the unarmed smack Alfred was captured and sunk twenty-

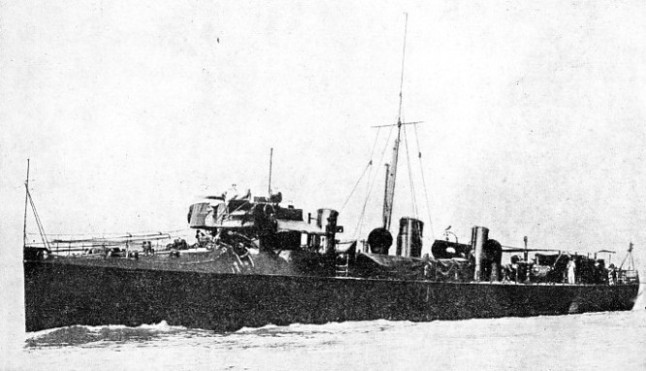

AN EARLY DESTROYER of the “A” class, H.M.S Lightning was destroyed by a mine near the Kentish Knock Lightship, north of the Thames estuary, in 1915. She was a vessel of about 300 tons displacement with a speed of 27 knots Four UC-

On that afternoon the steam drifter Gleaner of the Sea, which had been taken up by the Admiralty and commissioned, was lying at anchor off the Thornton Ridge, which is a shoal abreast of Zeebrugge. She and some other drifters had been placed there with their nets out to catch the Flanders submarines which used to come in and out of that harbour. The enemy's base at

Bruges was reached through the canal which is entered at the Zeebrugge lock. About 2 p.m. the watch on deck heard an unusual sound against the Gleaner of the Sea’s wire cable which led down to the anchor.

Having walked forward, the man was thrilled to see UB-

The Last of UB-

A second bomb was dropped where the sea boiled, and the skipper signalled another drifter, which came up and threw more bombs. Then the Gleaner of the Sea fetched a destroyer, which fired additional explosives. Oil and air bubbles continued to reach the surface, and that was the end of UB-

For their patriotism, zeal and total disregard of danger, these fishermen crews were beyond all praise. It was my privilege to command one of the steam drifters during part of the war

and after having lived with such splendid men through all the seasons and every kind of weather, I could never forget their rugged outlook on life, their simple philosophy, their loyal affection, their promptness in emergency. They had come straight from their North Sea fishing into the midst of a great and terrible war.

Scarcely one of them had ever fired a gun in his life, yet these clear-

So, in almost every kind of fishing craft the anti-

So also on the Yorkshire coast two of the local craft known as cobles were commissioned. A coble is an unusual kind of boat peculiar to such places as Bridlington. Filey, Scarborough and Whitby. These two were the Thalia and the Blessing, and they were fitted with auxiliary motors. They received 300 yards of mine-

Communication by Pigeon

Thus it was with ships as with human beings; some seem destined for adventure, others jog-

The Lowestoft smack G. & E., which had been in action with a UB-

On August 15, 1917, the two armed smacks Nelson and Ethel and Millie were fishing off the east coast. This was the year when the U-

There was now no need to waste an expensive torpedo. A few shells would suffice: for the German submarines frequently attacked while on the surface, using a 4.1-

Thus, with the advance of months, mystery smacks became a little old-

Thus, with the advance of months, mystery smacks became a little old-

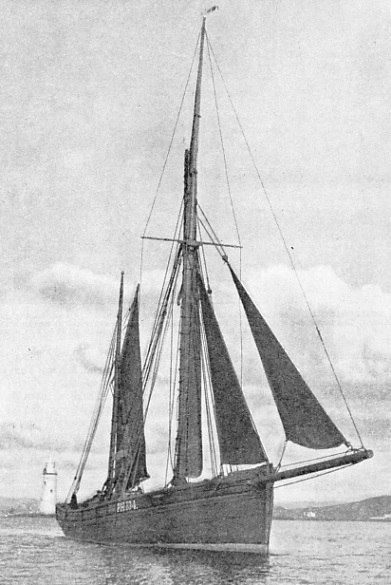

NOW A PLYMOUTH TRAWLER, the Treminster was formerly a Brixham, Devonshire, vessel. During the war of 1914-

The attack this summer’s afternoon began about 2.45 without warning. Everything had seemed quite peaceful. The Nelson was under way sailing on the port tack, the trawl had been shot, and one hand remained on deck looking after the steering and cleaning fish for the next day’s breakfast. Skipper Crisp was below packing the fish, but he presently came on deck, took a glance round the horizon — as every mariner by time-

“Clear for action!” shouted Crisp, and the men jumped to their thirteen-

This was serious misfortune, but every man remained perfectly cool, and the skipper in an endeavour to keep her from sinking put his ship about on the other tack. Two more shells followed. Now came the devastating seventh, which struck the skipper, penetrated the ship’s deck and the ship’s side, and fell into the North Sea. In poured the salt water, and the Nelson began to sink. The smack’s gun-

Terribly anxious minutes ensued. Only five rounds of ammunition remained on board, the ship could not float much longer, and the enemy continued to outrange with his superior gun. In spite of his sufferings, this great-

“Abandon Ship!”

His son went up to him and heard this next command: “Abandon ship. Throw the books overboard.” So the smack’s rowing boat was lowered, and they prepared to leave the foundering vessel.

That was the most painful situation of all. How could they go away and forsake the old man?

But the skipper was thinking of their lives, rather than of his own. “Tom,” he called to his son, “I’m done. Throw me overboard.”

That they certainly could not do, even in this awful crisis; yet the Nelson would not float many moments longer, and it seemed likely that her death would synchronize with that of her captain. Perceiving that he was too ill to be moved, they left him alone to his ship and his dying thoughts. Tom and the others got in the boat and rowed a few strokes. In less than a quarter of an hour Skipper Crisp and the Nelson sank simultaneously below the waves. The North Sea broke over them. Life had gone.

In bitter sorrow the survivors began an uncertain boat voyage. Their mates in the Ethel and Millie were a little better off. Robbed of their ship, they had been taken prisoner and were last seen on the submarine’s deck as she motored away. And now dark night covered the sea, as Tom Crisp’s party pulled wearily at their heavy oars. There would be little hope of seeing a ship before daylight. Towards morning the wind got up and blew them off their course, and it seemed they would be dead of starvation long before reaching Denmark or Norway.

To attract the attention of any passing ship — perhaps the Harwich cruisers might be coming home from a sweep into Heligoland Bight — a pair of trousers and a large piece of oilskin were secured to a pair of oars. Once a vessel was sighted, but she never saw the boat. Then a group of British minesweepers was seen, but they were too far away and passed by unsuspecting. So the long day faded into a second night, the weather improved, and the rowers pulled steadily on.

A CONCEALED GUN in the Q-

We can imagine the feelings of these men; the mingled sense of sorrow, anger, hunger, thirst, physical and soul-

But it never does to lose hope. Some of history’s sea-

Thus at last secured along the shipping route Tom Crisp and his companions were sighted during the same afternoon, rescued and taken into port. But that was not quite the end, for His Majesty King George the Fifth awarded posthumously the Victoria Cross to Skipper Crisp, and the D.S.M. to the son, who went to Buckingham Palace to receive these well-

But such is the fortune of war that within one week of Skipper Crisp’s death, the North Sea fishermen much farther up the coast were to be witnesses of a strange event which counterweighed the disaster. Three British mine-

Swift Retaliation

Having been ordered to lay mines near Dundee and Aberdeen, UC-

Having altered course to the scene of this explosion, they soon found their wire entangled, and up came a German mine. While the Thomas Young destroyed this danger, the Jacinth dropped two depth charges over the right spot, and more mines within UC-

Next day the armed trawler Sophron foundered on a mine at this spot, and yet another mine was discovered. The evidence thus pointed to the presence of some enemy submarine, though at this late stage of hostilities the Admiralty were not hurriedly convinced.

Prolonged salvage operations, however, were undertaken, and about one month after the initial explosion, a German twenty-

THE QUICK-

Late in September 1916, the Lowestoft armed smack Holkar, which had come out for the usual dual purpose of catching fish and submarines, was in the lower part of the North Sea. Her personnel consisted of Skipper Thompson (who had already won the D.S.C. for a previous episode), a mate, a petty officer lent by the Navy, a private of the Marines as gun-

At 8.15 a.m., on September 28, distant sounds of a submarine were heard on the Holkar’s hydrophone. One hour later the skipper and four others on deck were peering through the haze when they thought they saw a buoy.

Skipper Thompson, having satisfied himself that what he saw had definitely shaped itself into a submarine, kept his smack sailing about south by west, sending the motor-

Just as the enemy’s machine-

Here were noticed two interesting items — a kind of scum on the surface, with a strange smell as if from bilge water. It so chanced that the private of Marines in the Holkar had served in another of these mystery smacks at the time when a submarine, after having been shelled, had hurriedly disappeared. The man stated that both submarines left the same smell behind. Another of the smack’s crew confirmed that the “smell was horrible”.

Doubtless the Holkar’s visitor was another of the small UC class, but she was never seen by the smack again. Two pigeons were released to inform the Lowestoft Senior Naval Officer and later on the area of this engagement was swept and buoyed. It is true that an obstruction was discovered, but many wrecks abound here, so the story concludes without solution. The depth being over 120 feet, and the turbulent North Sea being thick with sand, no diver could be sent down, though nowadays modern appliances and up-

Curiously, this Holkar affair happens to be one of the few instances where the Admiralty made awards without complete evidence. Skipper Thompson was given a bar to his D.S.C., one rating received the D.S.M. and £1,000 was divided among the crew.

But what was the cause of the scum and “bilge water”? The latter rather strengthens the opinion that this boat dived voluntarily. Only after some while did the patrols learn this bit of bluff, and that (to deceive the hunters) an enemy submarine would after submergence release such things as oil and even pieces of wood. The practice became well established, and I have since received confirmation from the Master of a British steamer taken prisoner. During his captivity he noted that the submarine was forced on one occasion to use this deception with a view to feigning disaster.

Whether the Holkar did or did not destroy her rival, the submarine scarcely won a victory. This was one of the difficult instances which just failed to carry conviction. We needed only a little more proof, but the absence of confirmation left us wondering. In any event, no recompense could be too high for the smacksmen, who risked their ships and their lives every time they left port.

The biographies of these crews would make entertaining reading. I know of one smack in which the marine had already been through the Dardanelles campaign and thought this decoy work “an easy job”, and the cook had been torpedoed, shipwrecked, wounded by shrapnel and twice blown up by mines. Yet the work came as a relief after service in big ships and the uncertainty gave a spice of adventure.

TWENTY YEARS AFTER her U-

You can read more on

“Great Voyages in Little Ships” and

on this website.