© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Navy Week

Every year since 1928 the Royal Navy has admitted the public into the dockyards at Portsmouth, Plymouth and Chatham during Navy Week. Thousands of people are thus enabled to see the Navy at work

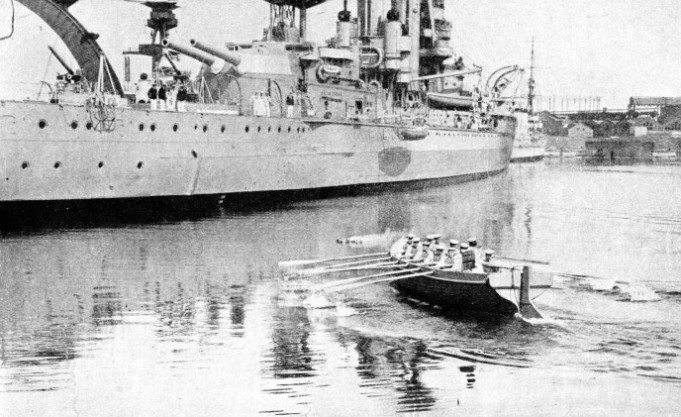

AT PORTSMOUTH. A ship’s boat is seen in this photograph near H.M.S. Iron Duke during Navy Week. H.M.S. Iron Duke, formerly a battleship, is now a gunnery training ship. Her present displacement is 21,250 tons and she is 580 feet long. She has a beam of 90 feet and a depth of 32 feet.

THERE are few Englishmen who have not heard of Navy Week -

Navy Week had its origin in the “Trafalgar Orphan Fund Pageants”. These so-

These processions collected about £1,300 annually for the fund. The money was urgently required, but it was felt that such methods were scarcely in keeping with the traditions of the Service. Moreover there were other naval charities which required financial assistance. Early in 1927, therefore, a proposal was put forward, and approved by the Admiralty, to hold a voluntarily organized naval pageant in Portsmouth dockyard during the workmen’s holiday in August.

The object of this first pageant week was to raise funds for naval charities, as did the Aldershot Tattoo for the Army and Hendon Air Display for the Royal Air Force. Despite bad weather the pageant week was such a success that Their Lordships authorized the holding of a “Naval Week” for 1928 This was held in the dockyards at Plymouth and Chatham as well as at Portsmouth. Since then this “Navy Week”, as it is now called, has been held annually at all three ports in August Bank Holiday week and the attendance of the public has grown from 198,258 in 1928 to 333,007 in 1935. There are two fundamental differences between Navy Week and the corresponding displays of the sister Services at Aldershot, Tidworth and Hendon.

In the first place, Navy Week is a far more democratic institution in that it caters for everybody on an equal basis. The poorest man in the street is on exactly the same footing as the millionaire. The admission charge of only one shilling (sixpence for children under fourteen) includes everything except luncheons, teas and refreshments, which are obtainable at popular prices. The only exception to this rule is the innovation in 1936 of admitting soldiers and airmen in uniform at half price with a view to stimulating that necessary comradeship and co-

The second point of difference is that for the Army’s tattoos and for the Royal Air Force displays many months are spent in training the performers, whereas no rehearsals for Navy Week are possible. A day or so before Navy Week begins, however, there is one afternoon’s rehearsal of certain events for the benefit of the Press.

The “arena” for Navy Week is the busy naval dockyard at each Home Port and for this reason it has always to take place during the first week of August, so as to coincide with the dock-

Until the very end of July, moreover, the ships and most of the personnel taking part in the various displays are at sea with the Fleet engaged upon their “lawful occasions”. Despite the lack of rehearsals, Navy Week is produced with that customary swing which the landsman expects of his Navy. The secret of this lies in the fact that Navy Week depends chiefly for its popularity upon the representation of the everyday life and work of the Navy, rather than on a specially staged and rehearsed spectacular display.

The chief object of Navy Week was originally to raise funds for naval charities, and still, every year, after the bare expenses of production have been paid, all the profits are allocated to these charities. The scope of Navy Week has now, however, been widened. It serves, in addition, to show the taxpayer that he is getting good value for his money and to educate the public to a realization of their dependence on the Royal Navy -

In contrast to the Army and the Royal Air Force, naval personnel includes representatives of almost every trade and calling to be found on shore. Naval men welcome all visitors on board during Navy Week, explain the mysteries of their wonderful ships and tell them how they live and work. The prospective recruit is much impressed by the cleanliness of the living quarters and by the standard of food. He is still more impressed by the fact that the Navy affords a certain career. Every man can serve for twelve years; the greater majority earn a good life pension after twenty-

Until 1932 Navy Week was organized and produced entirely on a voluntary basis; there was no permanent staff not even a paid secretary. All the work was done by officers and men in their spare time, when they would otherwise have been on leave. In 1932, for the first time, the attendance numbers showed a decline. The reason was that nearly everyone in the vicinity of the three Home Ports had already been to one of the five preceding Navy Weeks, and the existing temporary organization did not encompass people who lived farther afield.

Everything used in Navy Week, even the loan of Government stores and dockyard services, has to be paid for out of the admission fees, so that no expense in connexion with Navy Week ever falls on the taxpayer. It was found that the financial work entailed, with the allocation of profits to the many different naval charities, was becoming a fulltime business. In 1932, therefore, a retired officer of the Accountant Branch was given the salaried post of Secretary to the Navy Week Committee, and a publicity agent was employed at Portsmouth to advertise Navy Week.

Everything used in Navy Week, even the loan of Government stores and dockyard services, has to be paid for out of the admission fees, so that no expense in connexion with Navy Week ever falls on the taxpayer. It was found that the financial work entailed, with the allocation of profits to the many different naval charities, was becoming a fulltime business. In 1932, therefore, a retired officer of the Accountant Branch was given the salaried post of Secretary to the Navy Week Committee, and a publicity agent was employed at Portsmouth to advertise Navy Week.

DURING NAVY WEEK the general public may visit ships of the Royal Navy and watch the ratings at gun drill and other forms of training. This photograph shows the crew of a 6-

By 1934 the attendance figures were again rising. This was due to a wider distribution of publicity and to the establishment of contacts with the Press, the railways and commercial enterprises and ex-

At the end of 1934, as a result of this report, it was decided to form a permanent, salaried, administrative staff consisting of the following retired naval officers:

Admiralty Navy Week Liaison Officer (“A.N.W.L.O.”), with an office at the Admiralty -

Chatham: Navy Week Secretary, Lieut.-

Plymouth: Navy Week Secretary, Lieut.-

Portsmouth: Paymaster Captain H. C. F. Pinsent, the former Navy Week Secretary, to become General Secretary, with an office and an Assistant Secretary, at the Royal Naval Barracks, Portsmouth.

Commander Poland retired in March 1936, on selection for the post of City Marshal of London, and was relieved as Navy Week Secretary, Chatham, by Commander H. R. Bennett.

The Admiralty Navy Week Liaison Officer and the General Secretary at Portsmouth work for Navy Week as a whole. The Admiralty Navy Week Liaison Officer is charged with all publicity and acts as a, link with the Press, the B.B.C. and the civilian world generally. The General Secretary is in charge of the financial and secretarial work.

The Staff and Its Work

The General Secretary and his assistant -

Each Port Committee has as its chairman the Commodore in command of the Royal Naval Barracks. Each Committee consists of some twenty to thirty naval officers serving in ships or establishments of the Port command, with a representative of the Royal Marines and from the Home Fleet ships based on that port. They volunteer their services annually and, despite the strenuous duties of their Service appointments, undertake all the executive work of producing Navy Week in their spare time. At each port also hundreds of petty officers and men volunteer their spare-

The Director of Personal Services at the Admiralty -

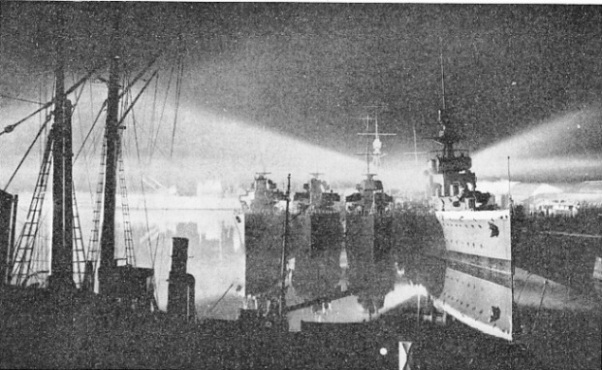

A SEARCHLIGHT DISPLAY in the naval dockyard at Chatham. There is nothing more impressive than the sight of warships silhouetted or illuminated by powerful searchlights. This occasion, in August 1935, was the first time that the public had been admitted to Chatham Dockyard after dark during Navy Week.

Few people realize the amount of work entailed by the organization and production of Navy Week. In its early days little was done beyond throwing open to the public the ships then lying in the port for their summer leave period. The few displays and demonstrations were those which required a minimum of preliminary organization. It is now necessary that Navy Week publicity should extend still more widely, so that those living in the Midlands, and even as far north as Scotland, may be enabled to see something of their Navy. Further, entirely new demonstrations have to be organized, so that those who have already been to Navy Week may come again and see more. Now, therefore, not only do the permanent staff have to start organizing next year’s Navy Week as soon as the last one is over, but also the volunteer committees are selected, and begin their work, in January, though the event does not take place until August.

If Navy Week were organized on a commercial basis with advance bookings and reserved seats at, say, 10s. 6d. a head, and extra charges for the many separate displays and demonstrations, its production would be a comparatively simple task. But this is not the object. It is the wish and intention of the Committee to keep it equally accessible to every one regardless of his income.

Hence every shilling spent on publicity, administration and production has to be most carefully considered.

Navy Week is therefore largely dependent for publicity and support upon the patriotic efforts of private individuals and commercial and public undertakings all over the country. These range from the retired naval officer and country parson living in out-

Navy Week is being held in 1936 -

At Portsmouth there will be also a series of most interesting tableaux, by naval men in the uniform of the period, of famous naval landing parties -

In a “theatre” at each port lucid and interesting demonstrations will be staged, with the help of moving models, accompanied by a running commentary and cinema projection, of four famous sea fights of the war of 1914-

Navy Week is a typically British institution. That its objects, ideals and administration are admired all over the world will be realized when it is recalled that in 1934 six German naval officers, and in 1935 two Japanese naval officers, were especially sent to Great Britain to study British methods and see their results. Germany then produced her first Marine-

Some of the British Dominions and Colonies, whose people realize their dependence on the Navy more than is done in Great Britain, now have their own Navy Weeks.

N avy Week is generally regarded as the best shilling’s worth of popular and instructive entertainment in the world. It appeals to the hearts of British subjects as does no other similar event. No matter what his status or calling, the visitor knows he will be welcomed; in-

avy Week is generally regarded as the best shilling’s worth of popular and instructive entertainment in the world. It appeals to the hearts of British subjects as does no other similar event. No matter what his status or calling, the visitor knows he will be welcomed; in-

AN INTERESTING DISPLAY given to some children during Navy Week at Chatham. A diver descends from a boat and the methods employed and the diving apparatus used are fully explained to the onlookers.

You can read more on “In the Royal Navy”, “The Navy Goes to Work” and

“The Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve” on this website.