© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Novelties in Ship Design

Inventors with revolutionary ideas in naval architecture were responsible, particularly in the nineteenth century, for the construction of many strange and remarkable types of ships, but the ambitions of the designers were seldom realized

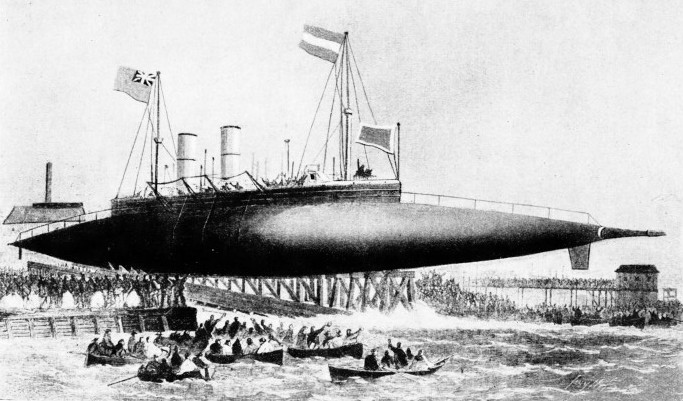

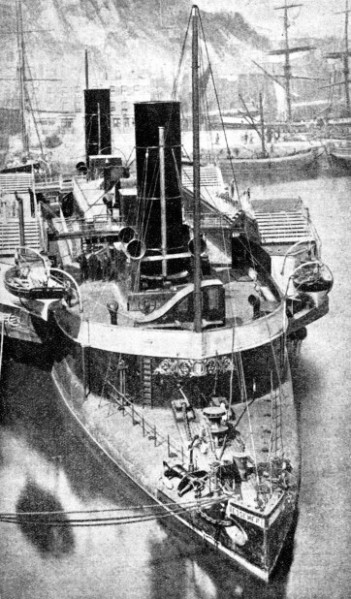

THE FAMOUS ‘'CIGAR” SHIP, built in 1866 by T. & W. L. Wynans in London, was named the Ross Wynans. This vessel had an overall length of 256 feet, with a maximum beam of 16 feet. Her engines worked at a pressure of 200 lb. to the square inch and were designed to give a speed of 22 knots. Despite the failure of her trials, a sister ship was built, the Walter Scott Wynans.

ALL through the history of shipping there has been a succession of freak designs in naval architecture. They represent attempts to produce a revolutionary ship that will overcome all the difficulties of the shipping industry and put its inventor in the way of a huge fortune. When the object is to eliminate certain excessive costs or other handicaps to trade, the inventor is often successful enough until the circumstances change. When, however, the inventor has attempted to evolve a hull form that will cope more successfully with the resistance of the water or with the effect of waves, he has never been entirely successful, because it is only the slow and studied development of existing features that proves of any avail.

Such freaks of naval architecture have existed from the earliest times, but large numbers of them have gone unrecorded or else are nothing more than a legend. Many of the pioneer steamers, for instance, might justly be described as freaks, for until the basic principles of steamship design were appreciated everybody had to work from entirely original ideas. The nineteenth century produced the-

One of the most interesting freak sailing ships dates from the beginning of the nineteenth century. The Transit was built in 1800 by Captain Richard Gower of the East India Company’s service. The war with France had shown that the ordinary lumbering merchant ship was handicapped through not being able to sail as close to the wind as the fine-

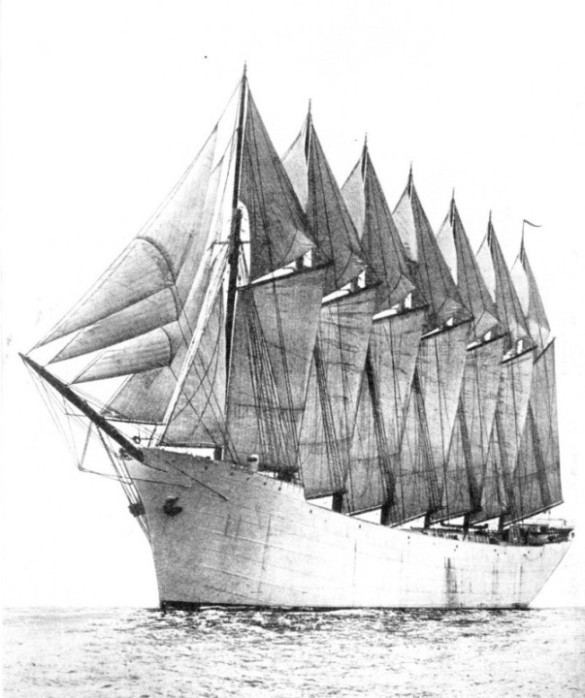

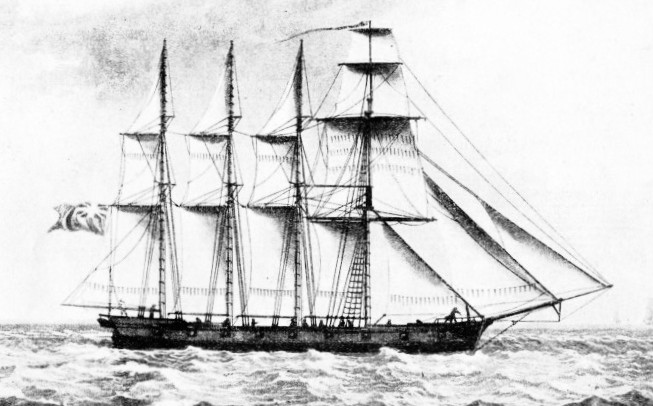

THE ONLY SEVEN-

In 1814 William Doncaster patented what was described as “the first hydrostatic ship which has ever appeared upon the habitable globe”. This vessel had five torpedo-

In the early nineteenth century there was a heavy tax on timber imported into Great Britain, even from the Canadian colonies, but ships built of timber were exempt from the tax. To evade this tax, John and Charles Wood, the shipbuilders who were responsible for the early Cunarders and for many other noteworthy vessels, had the idea of building a “solid” ship in British North America, so that she could be broken up on arrival in Great Britain, when her timbers would be undamaged and saleable.

The Columbus was built near Quebec in 1824. She was a ship of 3,690 tons, with a length of 301 feet, a beam of 50 ft. 6 in. and a height of 22 ft. 6 in. She crossed the Atlantic with difficulty and reached Blackwall on the Thames after many adventures. There her owners, against the Woods’s advice, attempted to send the empty shell back to Canada for another cargo. Disaster soon followed. In the meantime the Baron of Renfrew, 304 feet long, with a 61 feet beam and a height of 34 feet, was built in similar fashion and rigged as a four-

A similar scheme attracted attention at the end of the war of 1914-

The ’forties and ’fifties of the nineteenth century produced a great crop of freak inventions. The gold rushes to California and Australia had worked up a huge volume of passenger trade and the steadily improving economy of steam machinery allowed steamers to take part in trades which had been regarded as possible for sail only. In the Caloric of 1852 John Ericsson tried to dispense with steam and used heated air instead. The cylinders were to be suspended over the furnace fires. Large sums of money were spent without achieving the speed intended. The unconventional engines were finally replaced by ordinary ones. In 1854 Frederick Sang attempted to float a raft on a series of cylinders whose sides were fringed with narrow paddle floats. As the cylinders revolved the ship would be propelled forward with the minimum of resistance. It was an ingenious idea, but it proved to be a failure.

Similar to Sang’s ship was the Ocean Palace, the invention of an Australian named Wilcox. This vessel had a double cigar-

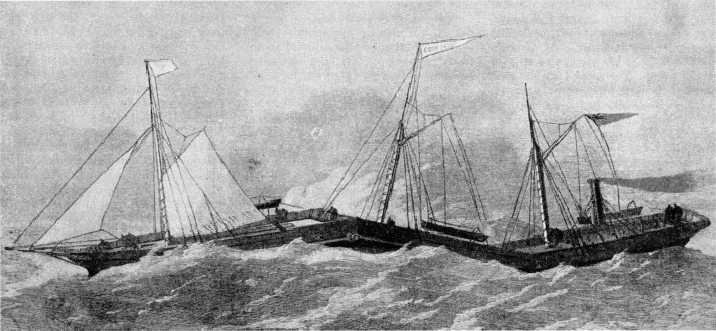

The advent of steam in the coal trade during the 1850s led to the building of many freaks in the following decade. The best remembered is perhaps the Connector, a ship built in three sections loosely joined together with hinges after the fashion of a toy snake. She was designed to ride comfortably in the roughest weather, undulating over the waves as if she were a sea serpent. On arrival at port with her cargo of coal she was to be divided into three sections for rapid discharge. The ship was built, but she was not a success.

THE THREE SECTIONS of the Connector were loosely hinged together to enable the ship to ride comfortably through heavy seas, with an undulating motion. The Connector was built about 1850. The three sections were designed with the intention of separating them, when the ship was in port, to facilitate the loading and discharge of cargo at different wharves.

In the same period the Civil War in America and the introduction of ironclads saw many abnormal fighting ships. The Confederates especially found it difficult to obtain materials for men-

Apart from these warships the most interesting sea-

Engines of novel design, working at a pressure of 200 lb. to the square inch, were estimated to give her a speed of 22 knots. She was a failure, however, although she aroused much attention and interest at the time. Undeterred by the failure of her trials, the brothers Wynans built a second ship, the Walter Scott Wynans. As soon as their owners died, these vessels were scrapped.

Chief among the freaks of the ’seventies were the circular ships or “ popoffkas,” and the weird ships built for the Dover-

An Imperial Failure

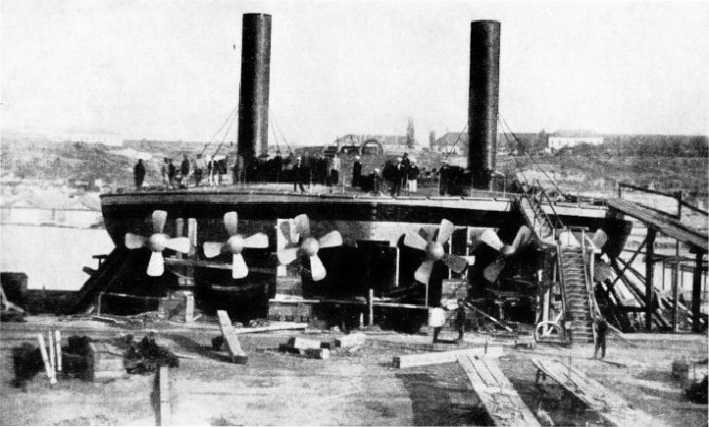

Popoff’s idea was to build a circular ship to provide an absolutely stable gun platform. The first of the type to be built, the Novgorod, was almost circular. She had a displacement of 2,490 tons. Her extreme diameter was 101 feet, and her draught was uniform at 13 ft. 2 in. Her sides were well protected and she mounted two big breechloaders. She was provided with six compound steam engines, each driving its own screw. The total indicated horse-

A CIRCULAR SHIP. The Vice-

The freak Channel steamers were even more interesting than the warships. The Paris Exhibition of 1867 had greatly increased the volume of cross-

Captain Dicey, formerly of the Indian Navy, had been impressed by the catamarans in Eastern waters. These craft were able to sail in heavy seas because of their double hulls. Dicey designed the Castalia to be a double-

THE BESSEMER, 1974 tons, had a saloon which weighed 130 tons. It was not fixed to the hull but was allowed to swing free. The intention was that it should counteract the rolling motion of the vessel in heavy seas.

Contemporary with the Castalia was the Bessemer, built at Hull from the ideas of the steel magnate Sir Henry Bessemer and of Mr. E. J. Reed, the naval constructor. Her dimensions were 349 feet by 40 feet, and she had a gross tonnage of 1,974. Her seaboard was low at either end, and amidships the superstructure rose to a considerable height. She was given two pairs of paddles for a speed of 20 knots, but in practice the after pair raced round in water that was already rushing astern, and 13½ knots was the most that she ever attained on service.

The most original feature of her design was due to Bessemer’s theory that the hull might be allowed to roll freely provided that the passenger accommodation was kept stable.

The “Calais-

With this idea in mind, a large saloon, 70 feet long, 35 feet wide and 20 feet high, weighing 130 tons, was built separate from the hull and set on gimbals in the same way as an old-

Soon afterwards the Express was laid down on much the same lines as the Castalia. The Express had a gross tonnage of 1,924 and engines of 3,600 indicated horse-

Numbers of freak underwater craft were built during the second half of the nineteenth century. Simon Lake built his Argonauts to run along the sea bed on huge wheels and discharge divers to examine sunken wrecks. Several other inventors worked on similar lines.

After the ram’s success in the American Civil War, the Polyphemus was projected for the British Navy in 1873, laid down in 1878 and launched in 1881. She was designed as a “torpedo ram” and was the first vessel to which a submerged torpedo tube was fitted. Apart from that, her only armament was a few light quickfirers to defend herself against torpedo craft. The upper part of the hull was built in the shape of a whale, and the exposed section was protected with armour so thick that most shells would glance off. She was the only vessel of her type to be built for the British Navy.

The Polyphemus was an uncomfortable ship, and spent most of her life in the Mediterranean. It was soon realized that she was far too slow to be used for ramming. Soon afterwards the Americans built a somewhat similar vessel, named the Katahdin, but she also was too slow for her purpose and was later used as a target.

In the early ’eighties, Robert Fryer completed twelve years’ experimental work by building his roller ship, Alice. In this ship a triangular deck rested on three huge wheels. These supplied the buoyancy, and had a series of buckets round their sides to act as paddle floats when revolved by the steam engines on deck. The edges of these circular floats were of heavy iron, so that when the ship reached land they would serve as wheels. The idea failed in practice. Following a similar scheme, a French inventor built the roller ship Ernest Bazin in the 'nineties with high hopes of revolutionizing naval architecture, but she lasted only for a few years.

In the ’nineties the whaleback steamer was evolved on the Great Lakes of America. She was a particularly ugly ship, and looked as if she really were a whale as she lifted her almost cylindrical hull, with its blunt snout bow, out of the water. It was claimed that this hull would save forty per cent in first cost and sixty per cent in fuel, but at sea it was a failure and was scarcely more successful on the Great Lakes.

Seven-

One of the last attempts to build a sailing ship that could compete satisfactorily with steam was made in North America at the beginning of this century. In 1902, at Quincy, in the state of Massachusetts, U.S.A., the Thomas W. Lawson was built by the Fore River Shipbuilding Company. She was a huge schooner of 5,218 tons gross, and she had seven masts. At the time there was a craze in America for many-

Many more ships of revolutionary design have been planned during the last hundred years, but have never been built. In his book, From Sail to Steam, for instance, Admiral Fitzgerald mentions a design by a distinguished naval architect for a novel warship. For the sake of economy, it was suggested that the vessel’s size should be limited to about 5,000 tons. She was to be low in the water, and her whole armament, her searchlights, signal mast, boats and navigating bridge were to be embodied in a single turret amidships, with the funnel running through the centre of this turret.

In recent years some ships of revolutionary design have been built and put into service. Among these is the successful “Arcform” ship, whose outstanding feature is a hull semicircular in section, with riveted instead of welded plates.

Another successful recent design is the “Maierform” ship, one salient characteristic of which is the yacht-

A FOUR-

You can read more on “The Biggest Sailing Ship of Her Time”, “The Famous Great Eastern” and “Rotor Ships” on this website.