© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Privateering

Once a legalized form of sea-

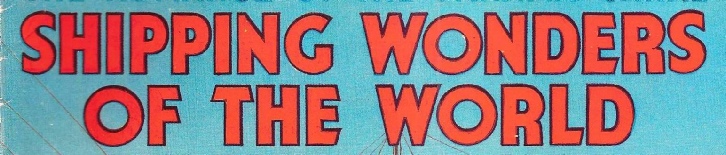

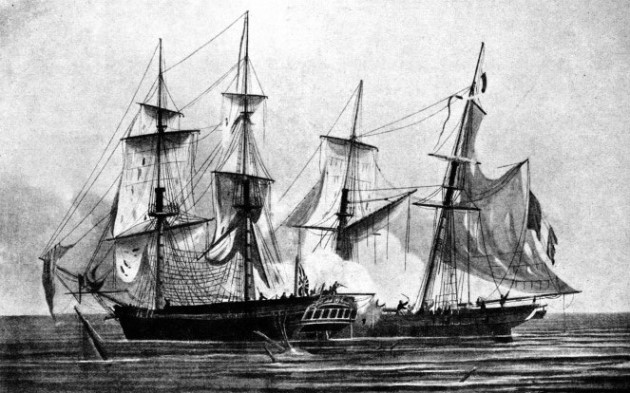

FRENCH AND BRITISH SHIPS IN ACTION. This illustration shows the capture of the Marquise d’Antin and the Louis Erasme by the famous privateers Prince Frederick and Duke in 1745. These two British vessels formed part of the privateering fleet raised by a syndicate of London merchants and commanded by George Walker.

WITH its splendid outlet for ambitious sea adventure, privateering exercised no small influence on British manhood through century after century. By the Declaration of Paris made in 1856 privateering was, however, rendered illegal, and thus passed away a unique form of activity that had afforded considerable profit to individuals and to the State.

Whereas a pirate or corsair is in the same category as a thief or a bandit, a privateer is one who has been authorized and commissioned to rove the seas subject to certain conditions. When Edward VI issued privateering licences, wealthy Devonshire gentlemen within a few years began to build ocean-

One of the most amazing privateering expeditions was in 1592, partly subsidized by Queen Elizabeth personally. It was remarkable for the vast profits which accrued and for the size of the ship captured. The captured vessel was named the Madre de Dios, which had sailed from India on January 12, bound for Spain with a valuable cargo of precious stones, elephant tusks, quilts, Oriental carpets, spices and other commodities. This big carrack was made a prize one night during that summer in the Atlantic by an English privateering squadron, and in September she was brought safely to Dartmouth, where she created a sensation. Of 1,600 tons and carrying over 600 men, she measured 165 feet from beak-

The value of her cargo, reckoned in modern money, amounted to over £2,500,000, but the pilfering which soon began prevented the privateering syndicate from receiving anything approaching this sum. Rough, hearty, poor Devonshire mariners, whose greatest wealth had never been more than a few shillings, helped themselves to necklaces of Oriental pearls, chains of gold, single pearls of exceptional size, forks and spoons of crystal set with gold and stones, bracelets, diamonds by the hundred and other valuable articles.

Never again could privateering be expected to yield such remuneration, yet it still attracted adventurous characters. During the earlier part of the seventeenth century much vexation was caused by the delay in paying the crews’ wages in ships of the Navy. Many a fine sailor, therefore, preferred going to sea in a privateer, where the men could count on receiving one-

During the time of Pepys those privateers who belonged to the port of Dunkirk used to be a source of no little anxiety to British merchant ships. Such privateers were fast vessels, not over-

The eighteenth century became the golden age for privateers of more than one nationality, because the political conditions of that time favoured such activities. As the French Navy during that century declined, so much the more did French privateers prosper, with the encouragement of the Government. Even at the close of the seventeenth century they used to cruise along the Gulf of Mexico, past the coasts of England’s new colonies — Virginia, Carolina and New England. The French ports of St. Malo, Dunkirk, Bayonne, St. Jean de Luz, Rochefort and Bordeaux developed into notorious nests for these adventurous fleets, which were financed by joint-

The Dunkirkers were such a scourge in the English Channel that vessels homeward-

45 Privateers from Two Ports

The men were hand -

GEORGE WALKER’S FLAGSHIP in October 1747 was the King George, a 32-

Eighteenth-

One Bordeaux private ship, called La Gironde, armed with sixteen guns and manned by a crew of 126, made two long Atlantic cruises between Christmas 1797 and the following November. During that period she captured no fewer than fifty brigs, as well as other vessels. Then there was Le Vaillant, of 700 tons, having twenty guns, with 105 men. She sailed across the Atlantic in 1801, and in seventy -

This sort of venture had its risks and even its reverses. No one but a genuinely courageous fellow would embark on such voyages. One day a French privateer sloop working the English Channel came upon a small hoy from Poole. The fight went on with great determination, and with bravery on either side, but the English skipper, William Thomson, with only one man, a boy, and two small guns, was eventually so successful as to wound half the French crew and then to capture the privateer, with eight prisoners. For this brilliant bit of work the Admiralty presented Thomson with

a gold medal and chain valued at £50. Certainly in those days there was plenty of excitement in voyaging. During the autumn of 1702 the Bristol galley Charles, 100 tons, mounting ten guns, and with a crew of fourteen, set out from Bristol bound for the West Indies.

Most of the galleys of the eighteenth century were built either on the Thames or at Bristol, being ship-

The Value of Speed

London merchants at that time imported many a cargo by galleys to Bristol to avoid the English Channel privateers. The galleys unloaded their goods at Gloucester, whence the commodities travelled by land to Lechlade, Gloucestershire, after which they were transported by barge down the Thames to London in safety. The reverse process was adopted when the galley voyaged outward-

The Charles sheltered a while in Cork Harbour and then set out to cross the Atlantic, but within six hours was being chased by a French privateer which was waiting off the Old Head of Kinsale. The Frenchman, on closing the Charles, met with such a furious reception for an hour that she sheered off and preferred attack on a brigantine named Logwood. Night came on, the Charles escaped, and sailed south to the Azores. Here she was again surprised. This time the privateer hung on to her for three days, when the galley’s superior speed allowed evasion and, steering a westerly course, the Bristol vessel made the best of fair trade winds till some thirty miles short of Barbados.

Then came another unpleasant surprise. At seven in the morning up sailed a French privateer, armed with six guns and seventy-

The French vessel was driven off, but little did she know that the Charles had expended all her shot save three, having been even compelled to cut up her bolts, besides collecting all the spike-

slow sailer, again fell into the enemy’s hands, though her crew got away and was brought by the Charles into Barbados.

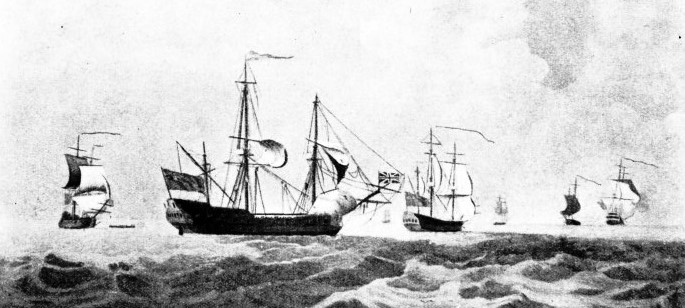

AN AMERICAN PRIVATEER IN ACTION off Halifax Harbour, Nova Scotia, on May 29, 1782. The illustration shows the engagement between H.M. brig Observer (left) and the American privateer Jack. The Americans were among the most successful of all privateers. They were particularly successful in intercepting British supplies.

Such incidents emphasized the great value of speed. For this reason privateers and merchant skippers used all sorts of dodges for getting the best out of their ships, making them sail closer to the wind. They would paint the underwater portion of the hull with a mixture of tallow, resin and sulphur to prevent fouling from the tepid waters. The stately East Indiaman of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, if not in convoy, was always a most tempting bait for any powerful French privateer. On the other hand the East Indiaman used to keep a smart look out and suspect any strange vessel on the horizon. Not infrequently the East Indiaman so impressed the privateer as to make her decide to clear off.

Legally there was no difference between a “letter of marque ship” and “privateer”, and “privateer” came to be used for both. Originally a letter of marque, mart, or reprisal, was a licence authorizing subjects to make reprisals for certain losses sustained at sea against the enemy. That is to say, the injured merchantmen were allowed to recoup themselves and to state the amount before the Admiralty Court, though after about the middle of the seventeenth century letters of marque were given to vessels not for particular, but for “general” reprisals. During the following century we find this distinction — a letter of marque ship was a vessel engaged on a trading voyage, with permission to make prizes if chance should offer, but a privateer was a private merchantman fitted out by her owners as a temporary man-

Need of Extra Hands

The privateer needed these extra hands not merely for the guns and close fighting, but also for sending into harbour any captured prize. Either of these licences was much to be desired, for two additional reasons. First, it exempted the cargo vessel from convoy. Thus, if she were a fast sailer and her captain one who delighted in risks, he could avoid much delay and arrive home long before other vessels. Secondly, this document nominally exempted the crew from being impressed. During

the war with France and. Spain (1625-

A HAND-

An English privateer of the mid-

“The Caesar privateer. A prime sailor and built for that purpose, with the best accommodation, Ezekiel Nash, Commander. Burthen 360 tons, 20 nine-

Nash can have had slight difficulty in finding a crew, for before the month was out the Caesar put to sea with the London privateers Defiance and Boscawen. On April 12, 1757, the Caesar was cruising about the Bay of Biscay, forty-

The French privateer was nearly twice her opponent’s size, being of 700 tons, with twenty-

For two hours and forty minutes the fierce engagement continued, but the Caesar herself had suffered such damage that she was compelled to bear up before the wind and stop some of her leaks. Already the ship had 7 or 8 feet of water in her hold, her masts were injured and part of her rigging had been shot away.

An Indecisive Contest

All hands were needed for pumping and bailing, and carpenters were slung over the side to plug the shot holes. By 5 p.m. so much progress had been made that there were now only 4½ feet of water in the hold, and the ship was ready to renew the fight.

So the Caesar then ran down under her opponent’s lee quarter, rounded under the stern, and once more fired a broadside. The Caesar once more suffered some ugly holes in her hull, having received two just above the water-

being too near a lee shore, stood out seaward. Her crew spent the dark hours stopping leaks and working the pumps. By 9 o’clock next morning, with rigging set up and everything in readiness, she sailed alongside the Frenchman and hailed the vessel to surrender.

The French ship’s name was Robuste, and she carried an exceptionally large crew of seventy-

ONE OF THE MOST FAMOUS PRIVATEERS was the 30-

Privateering at the best of times could only be a great gamble, yet it did form a service valuable to a Government at war, especially during the American War of Independence (1775-

Rogers was born somewhere about the year 1679. The son of a Poole (Dorset) mariner he felt a natural inclination to the sea. In 1708, financed by sixteen Bristol merchants, he fitted out the two ships Duke and Duchess.

These sailed from Bristol on August 2, and anchored in Cork Harbour five days later, where Rogers promptly lost forty of his men by desertion. Here also he careened, scrubbed, and tallowed the hulls of both ships, so as to be ready for a long voyage. He obtained some men from the shore to replace the deserters, and doubled the number of his officers.

As master and pilot Rogers took with him William Dampier, one of the finest seamen that England has ever reared. Born in Somerset, Dampier had already had an amazing career. Having fought against the Dutch in 1673, he got a job as overseer of a Jamaica plantation, but a few years later went buccaneering, crossed the Isthmus of Darien, and captured more than one vessel in the Pacific. Then he sailed round the world and explored the coast of Australia. He was wrecked on Ascension Island, but finally reached home.

Having left Cork Harbour on September 1, 1708, the three-

Having crossed the Atlantic, the Duke and the Duchess went south towards Cape Horn, sighting the Falklands two days before Christmas The usual fog and bad weather were experienced as they neared the Horn.

Original of Robinson Crusoe

On the last day of January 1709 the two frigates sighted the lonely island of Juan Fernandez, off the Chilean coast. A boat was lowered and returned with an abundance of crayfish, and also with a wild-

Continuing his privateering voyage, Rogers captured a small prize which he fitted out as a man-

Apart from the matter of fighting and capturing, this undertaking over uncharted oceans was invaluable to the English nation. On December 27, 1710, Rogers reached the Cape of Good Hope, remaining in Table Bay till the following April. Some of his spoil he sold to the Dutch settlers. Then he crossed the Equator for the eighth time since he had left Bristol. Finally he sailed for safety with a convoy outside Ireland, down the North Sea, and thus on October 14,1711, arrived in the Thames at Erith. With the Duke and the Duchess was the captured Spanish galleon whose name had been changed to Bachelor.

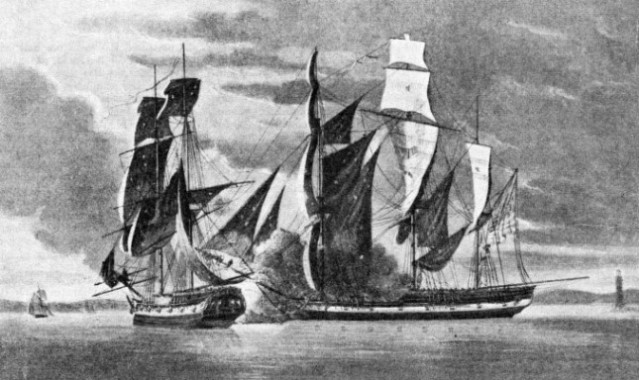

THE SINKING OF A BRITISH PRIVATEER by the St. Malo (France) privateer Vengeance in 1757. The 26-

You can read more on “Chinese Piracy”, “Handling the Sailing Ship” and “Life in the East Indiamean” on this website.