© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Ship Types and Deck Arrangement

From the general appearance of a merchant ship and from the number and arrangement of decks, it is often possible to tell the nature of the trade on which she is employed or for which she was built. Thus deck arrangement forms a suitable key for the classification of merchant ships

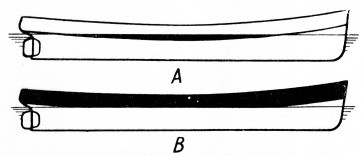

THE TWO PARENT TYPES from which the majority of merchant ship types are derived. The upper figure, A shows a two-

THE number, disposition and arrangement of decks and superstructures of a vessel are governed by the particular trade upon which the ship is destined to operate, the ports and their equipment at which she will normally call, and the character of the goods to be conveyed. However efficient the vessel may be when used for the purpose for which she was designed, she may be a total failure if called upon to do other work.

A vessel built to carry cargoes of light specific gravity needs the maximum cubic capacity of hold space available, and all structural details are arranged with that end in view. A vessel carrying, say, coal or ore in bulk requires only a normal cubic capacity, but as an offset large easy trimming hatches are necessitated. A vessel, therefore, designed as a collier will be totally unfitted for the transport of light cargoes.

Since the majority of shipowners have their craft built to meet their particular needs, it follows that an inspection of vessels in a dock or alongside a wharf will generally disclose craft of all shapes and sizes, some low down in the water, some riding high; some with the minimum of deck erections, masts, derricks and the like, as against others with whole batteries of masts and booms.

The average onlooker may view with bewilderment the variety of craft he sees, but one who is used to ships and shipping will appreciate that virtually all vessels conform to one of two basic types. It is interesting to follow the evolution of modern ships from these two parent forms.

Consider the vessel having single flush deck without erections. The single flush deck type would carry cargo safely, but with the coming of the steam engine it became apparent that something more than a casing was needed to protect the machinery department, funnel, ventilators and the like. A short bridge was therefore evolved, which afforded an elevated position for the steering and controlling of the vessel.

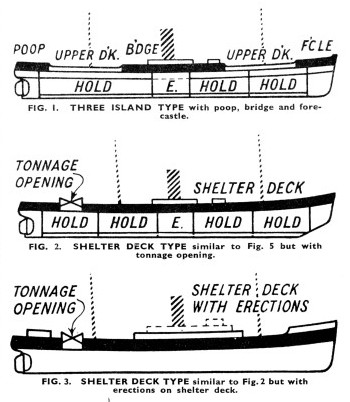

The effect of heavy seas breaking over the bows and stern led to the introduction of a poop and forecastle. These superstructures, with the bridge, not only added to seaworthiness, but also provided a reserve of buoyancy which, by increasing the permissible draught, also augmented the vessel’s carrying capacity.

We thus arrive at a vessel with a single deck surmounted by a poop, bridge deck and forecastle with two wells between these detached superstructures. As vessels grew in size it became necessary to fit one or more complete or partial decks below the upper deck to take best advantage of the available hold capacity when carrying mixed cargoes.

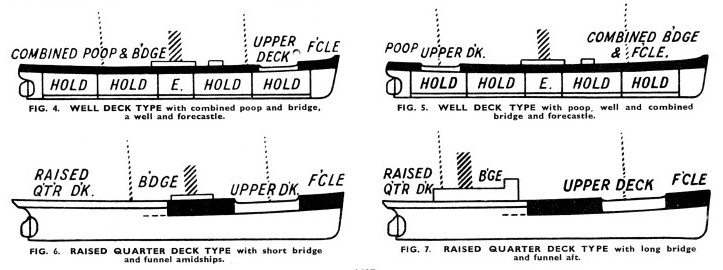

With the machinery situated amidships, particularly in smaller vessels, it was evident that a proportion of the space available for cargo was lost, due to the shaft tunnel. To make good this deficiency at minimum cost, the raised quarter deck was introduced. This, in effect, is obtained by lifting the upper deck by three to four feet aft of the machinery space, the structure of the vessel being duly compensated for the loss of longitudinal strength at the break or step in deck levels. As vessels became more specialized it was found convenient to move the machinery to the after end of the vessel, and craft of this type are largely found engaged upon coastal trades. All modern tankers are of this type with machinery aft.

One effect of this transference, especially with coasters carrying dry cargoes, was the difficulty experienced in trimming the vessel on an even keel, with a homogeneous cargo. Here again the raised quarter deck became of service as the added cubic capacity available between amidships and the forward end of the machinery space enabled the cargo to be stowed to ensure an even keel, in a laden condition.

Modern coasting vessels appear, therefore, with a raised quarter deck, usually with casings over (but occasionally with a poop), a relatively short bridge deck at the break in the main deck and a forecastle. Vessels of this class are known as the three island type (see Fig. 1) because of the three “islands” (poop, bridge and forecastle) which rise from the main deck level in outline.

Coasting vessels, which have to ply under bridges with restricted headroom to reach their destinations, are found with possibly a raised quarter deck, no independent bridge deck, and with a monkey forecastle — a forecastle sunk partly through the main deck.

With the experience obtained as the years went by, the bridge deck of the three island type of vessel grew longer, with consequent shortening of the wells, until ultimately these superstructures became merged into one and the shelter deck vessel was evolved (see Fig. 2). A shelter deck vessel is virtually a two-

With the experience obtained as the years went by, the bridge deck of the three island type of vessel grew longer, with consequent shortening of the wells, until ultimately these superstructures became merged into one and the shelter deck vessel was evolved (see Fig. 2). A shelter deck vessel is virtually a two-

In a full scantling vessel with two decks — and looking externally akin to a shelter deck vessel —the top deck is the strength deck and with the free-

Every vessel afloat conforms in principle to one of the two parent types, and the addition of lower decks, awning deck or superstructures, the disposition of the machinery, and the arrangement of the hatches are simply variants to suit the trade of the vessel. Bound up with the evolution of ships are also the efforts of builders and owners to ensure that their vessels will not be unduly penalized for tonnage, port dues and the like. Hence we find structures on deck purposely left open, and tonnage hatches fitted to shelter decks to reduce as far as possible the net register tonnage.

It is often a condition of a contract that the shipbuilder must design the vessel so that the tonnage measurement will be the minimum compatible with the dimensions.

The illustrations are representative of some of the types described. Figure A (at the top of this page) shows a two-

Cargo and Passenger Liners

The raised quarter deck type is popular for coasting vessels, and in particular for collier work. The old steamer is being rivalled severely in this class of work by the small motorship which, because of her modest dimensions, can navigate far up rivers and discharge at wharves which normally would be inaccessible to the bigger ship. Most of these motor coasters are single-

The shelter-

Many large passenger liners to-

The well-

All the types mentioned above have been built up on technical grounds after years of experience and evolution. They are governed to a certain extent by tonnage measurement regulations. If these should be revised for reasons of the small space which modern machinery takes up, then ship structures will be altered with them.

You can read more on “Building a Liner”, “How the Modern Ship is Tested” and “Merchant Ship Types” on this website.