© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Thames to Tahiti

A first-

GREAT VOYAGES IN LITTLE SHIPS -

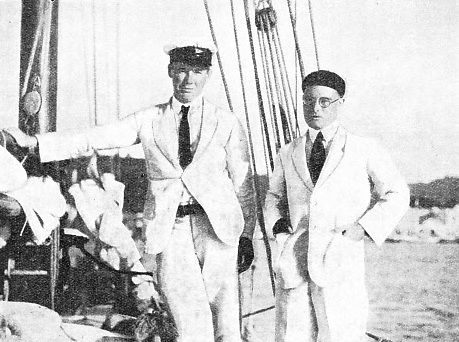

THE AUTHOR, Sidney Howard, at Tahiti, at the end of his 12,000-

ON July 7, 1931, the 38-

Panama! What magic there is in the name -

I always felt sorry for Pacific Moon in those days. She had been considerably altered before I joined her, and when I arrived, instead of being ready for sea, she looked a shabby, neglected hulk. There seemed to be something wrong with almost everything I touched, and I always felt resentful of her name. She was originally Nama, and was built to the order of a well-

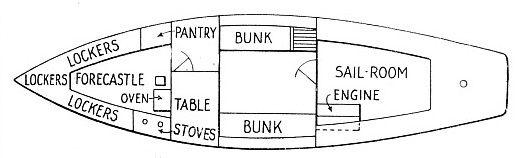

ACCOMMODATION PLAN of the 38-

She was 38 feet overall, 33 feet on the water-

I knew that Pacific Moon would be a dirty boat at windward work, but the shape of her stern was right, and I knew she would run steadily before the trade winds without yawing or inviting a wave to break over her stern.

The low free-

horse-

Almost a year after I had gone to the East Coast to be a sort of cook-

His local name was “Mad Jack”, because he sailed his 15-

Now that I was sole owner, and in full charge of my property, I felt a new man, able to give Pacific Moon her chance. I had a second-

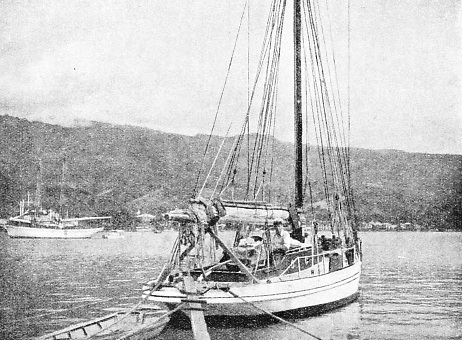

FITTING OUT at Oulton Broad, near Lowestoft, Suffolk, in 1930. The author is on a boatswain’s chair up the mast, which he is sandpapering in preparation for repainting.

We took the yacht to the Camber, which is the former submarine basin in Dover Harbour, cleared a lot of rubbish out of her, and did a little sailing. We started in the early hours of a Friday, but found no wind, so we went along under power to Boulogne. Fog kept us there for a day or so, and then we went out of Boulogne under power, bound for Cowes, where I intended to buy a barometer. I had a five-

All night we ghosted along towards the Isle of Wight. At 10.30 on Sunday morning I switched on the radio and had a comforting weather forecast from Daventry to the effect that the light airs from the south and south-

Reefing was a nasty job, because the rags of the sail fouled the jib halliards, and John had to go out on the end of the bowsprit and fight the tangle as the bowsprit dipped him under the waves.

The same squall capsized a French excursion steamer on the other side of the Channel and drowned 400 people, and then screamed over England, doing damage as far inland as Birmingham. We reefed, hove-

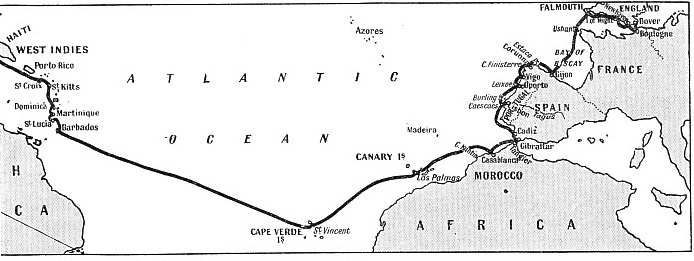

I went by road to Shoreham, where I ordered a new sail to be sent to Falmouth, and when the weather moderated Pacific Moon plodded along under trysail and engine, and reached Falmouth after various calls. Here John decided to carry on with me for the whole voyage. We collected the new sail, loaded up with stores, and set off for Spain in haste, because a north-

I was too exhausted to worry more about navigation. I knew my own position; a seasick yachtsman in the Bay of Biscay, and I was not interested in the exact spot occupied by the yacht. The constant procession of ships on the steamer lane between Ushant and Finisterre gave us the correct course. At the end of thirty-

I decided to give up beating to and fro across the shipping lane and to steer south as long as the yacht would lay that course, putting in at a Spanish port on the north coast to await a favourable wind.

A day later the wind had dropped, and the yacht rolled in the long swell of the Bay. We took a few sights with the sextant, and I prepared to devote the night to the study of navigation, as the yacht was becalmed. In Southampton I had bought a book which gave various methods, including the old-

We left Gijon for Corunna, about 150 miles away on the corner of Spain, and had some more wet work to windward getting past Estaca Point, the most northerly point in Spain. Directly the Pacific Moon put her nose outside Corunna to go round Cape Finisterre to Vigo, up came a head-

Anxious Moments

On the way we were befogged, and were drifting all night among fishing vessels which were so close that we could hear the fishermen talking. We were unable to get out of their way, as the engine, which developed a “temperament” directly we left England, was out of action. Off the Burlings a gale started to spring up from the north, and we sped into the Tagus at a great pace one sunset, bringing up off Cascaes, a seaside resort of Lisbon, as darkness was falling and during a gale. In the morning the gale increased in shrieking fury, and a trawler dragged her anchor, crashed down on to another fishing vessel and caused her to drag, so that both vessels’ anchors fouled our anchor chain. The strong ground tackle of the Pacific Moon hell, but the two vessels threatened to swing inwards and crack the little ship between their cumbersome hulls. The trawler paid out more cable and dropped clear astern, but the other vessel, a schooner, touched our starboard bow. John scrambled aboard this vessel and helped the men to fish up the trawler’s anchor -

Lisbon marked a long struggle with the engine, which, however, refused to function. So we sailed for Gibraltar, putting in at Cadiz. The engine was taken out and overhauled at Gibraltar and the yacht was hauled out, painted, and tuned up for the Atlantic passage. The next stop was Tangier, after which we made for Casablanca. This is a desolate part of the African coast; rollers form a good way out, and on one occasion we had an anxious time. We were approaching the shore with a commanding breeze to look for a shore mark mentioned in the pilot book, when the breeze failed and we were in the influence of the rollers. The engine, despite its recent overhaul, was already out of action, but we were saved by a light breeze which enabled us to claw off shore.

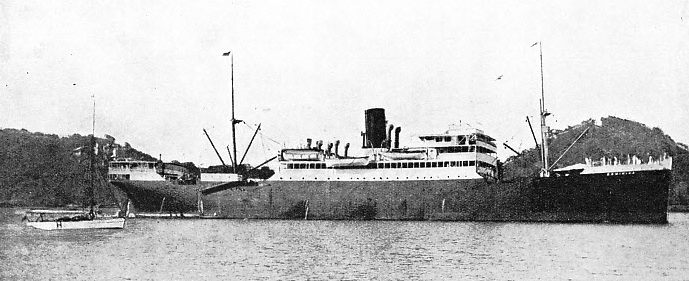

IN THE WEST INDIES. The Pacific Moon (left) near the SS Dominica, in the harbour of Port Castries, St. Lucia. The Dominica (4,856 gross registered tonnage) formerly belonged to the Bermuda and West Indies S.S. Co, Ltd., and was built in 1913. The Crown Colony of St. Lucia is the largest and the most attractive of the Windward Islands.

Getting into Casablanca Harbour at night caused anxiety. There was only a breath of wind, and we were worried because a light did not show the colours recorded on the chart. The wind dropped, and the current swept the yacht towards the harbour breakwater; but John dropped the dinghy over the side, and managed to pull the head of the yacht round while I steered. We nursed her out of the shadow of the breakwater and anchored till the morning brought a faint air enabling us to sail into the harbour. I doctored the engine in Casablanca Harbour, and thus we were able to leave under power one afternoon until, picking up a nice breeze off shore, the engine was stopped. That night we had a typical tornado. This is not the type of hurricane known under the name of tornado in America, but is a storm peculiar to that part of the African coast. It is accompanied by thunder and lightning, and is remarkable for a peculiar lull during which rain falls in torrents. This tornado was a mild affair, but it was wonderful to see the lightning play over the hills of Africa. Then came a pause and rain, followed by the wind, which arrived with a bang from the opposite point of the compass.

Taking our departure from Cape Kantin, we set a course for Las Palmas, Canary Islands. The wind increased to gale-

We left Las Palmas and intended to sail non-

In twenty days the Pacific Moon blew before the trade wind to Barbados, covering some 2,100 miles. Sailing before the trade wind is a delightful experience. The light clouds, the sun, the moon, the stars and the vessel all seem to be caught by the great urge westward and the whole universe is in harmony. For nearly three weeks we had the sea to ourselves, sighting the lights of only one steamer when we were nearing Barbados. Being so close to the sea that we could touch it by putting a hand over the side enabled us to obtain a close view of the wonders of the ocean. I never knew before that fish are so playful. I have seen a school of them pitch-

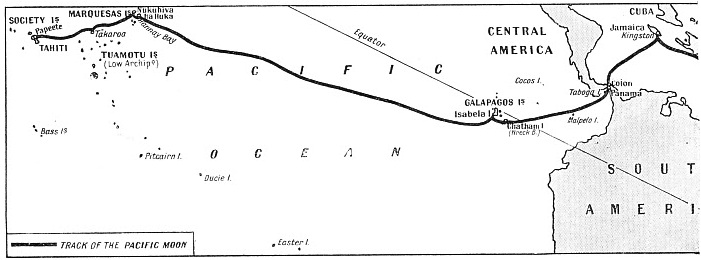

TWO OF THE WORLD’S GREAT OCEANS, the Atlantic and the Pacific, were crossed in the Pacific Moon by Sidney Howard and his companion, John W. Johnstone. The Pacific Moon was 10 ft 6 in beam, and drew 6 feet. Her net registered tonnage was eight, and her Thames measurement fourteen tons. She set sail from Dover on Friday, June 12, and from Falmouth on July 7, 1931, crossing the Bay of Biscay to Gijon, in northern Spain. After having called at various ports in the Iberian Peninsula, the Pacific Moon was overhauled at Gibraltar for the Atlantic voyage. Casablanca was the next port of call; then the route was via the Canary Islands and Cape Verde Islands to Barbados, in the West Indies. After the passage of the Panama Canal, the intrepid yachtsmen sailed via the Galapagos Islands across the Pacific to the Marquesas. Tahiti was reached on July 12, 1932, after a voyage of 12,000 miles.

We kept four-

I was navigator, cook, and engineer in my spare time, while John was marline-

We were both keen oil getting the best out of the yacht. Possibly we should have had an easier time had we been less particular, but we should not have gone so fast nor so far without stranding or other mishap due to slackness. The first storm in the Channel had convinced me of my luck; in finding John I had lighted upon a born sailor and a great-

THE END OF THE VOYAGE. The Pacific Moon moored in Papeete Harbour, Tahiti, after a voyage lasting a year and five days. Here the yacht was sold to a young Argentine. Sidney Howard, after spending some time in the South Seas, went by steamer to New Zealand and Australia, and then returned to England. Johnstone returned from Tahiti to Europe in a French vessel.

A calm means that there is no wind, yet the ocean is never still. Idle sails flap-

We picked up Barbados on the end of the bowsprit, and anchored. A long period of refitting began, during which we enjoyed ourselves ashore. When the yacht was refitted we went from island to island in the West Indies, finishing at Kingston, Jamaica, where we had to consider fresh plans. John proved amenable to my idea of going to the South Seas, but protested that we had no chronometer. To satisfy him, I bought a second-

The canal looms large in the thoughts of every yachtsman bound for the Pacific. At sea we had room and were in nobody’s way, but I was haunted by the fear of engine trouble in the middle of the canal, through which the authorities do not allow vessels to sail. After various opinions had been given on the failure of the engine, and the magneto had been examined and blowlamps had been applied to the cylinders, John discovered the cause of the trouble. One of the two water-

Eighty-

One afternoon the pilot came aboard and we motored up to the Gatun Locks. There are three series of twin lock chambers here, each chamber being 1,000 feet long and 110 feet wide, and vessels are raised a total of 85 feet above the Atlantic. We tucked in behind a steamer in the first chamber, and the great gate closed silently behind us. To my surprise the attendants did not arrange to have warps from either side so that the yacht could be kept in the middle of the chamber clear of the sides. When I questioned the pilot he said they always locked yachts through with one set of warps on one side; everything was going to be all right, and as long as I saw that the engine was running he would look after the boat. Each chamber uses about 3,000,000 cubic feet of water at a filling, the total capacity being double this amount. Flooding began, and mad eddies and boiling currents gripped the yacht, tossing her about as if she were a match. There was little purchase from the almost vertical warps, and when I let in the clutch, in response to the pilot’s order, the propeller had no effect in the turmoil of water that shot into the chamber with terrific force. The port quarter of the yacht was pinned against the side of the lock as the yacht began to rise towards a projection. Silence is the order of the Panama Canal, but John let out a yell of warning that shocked the pilot and scared the negro attendant, who was sitting on the cabin top. Frantically we tried to shove off. Then another eddy swung the stem clear, but shot the bowsprit against the wall. I jabbed at the wall with a deck-

By the time the first chamber was full and we moved into the second, the pilot realized that the propeller had no effect when the water was boiling in. But the attendant was now wide awake and therefore taking greater care, so that we had better luck in the second chamber, and again in the third. We were ordered to moor for the night in Gatun Lake. The pilot left us, but the negro had to stay for the whole transit. Next morning a new pilot arrived at dawn, and we started. The pilot said he owned a sailing boat, so we set the mainsail and this helped the engine. Unfortunately the pilot let the sail gybe and carried away the socket for the flagstaff on the stern, so that the Pacific Moon finished the transit without showing the Red Ensign.

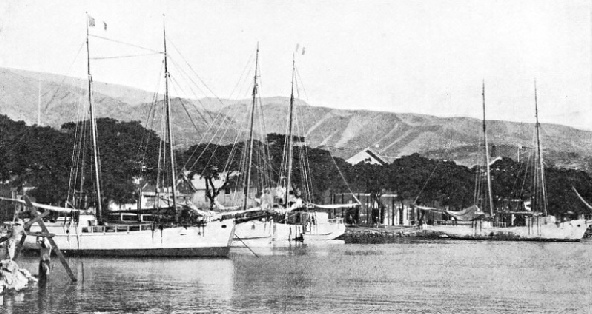

THE HARBOUR OF PAPEETE, Tahiti. South Sea Island schooners are moored at the wharf. These schooners have auxiliary power and are manned by the Islanders who are expert seamen, at home in all weathers. They are familiar with all the intricacies of the coral reefs of the South Sea Islands.

THE HARBOUR OF PAPEETE, Tahiti. South Sea Island schooners are moored at the wharf. These schooners have auxiliary power and are manned by the Islanders who are expert seamen, at home in all weathers. They are familiar with all the intricacies of the coral reefs of the South Sea Islands.

We entered Pedro Miguel Lock behind a big Japanese liner and descended 30 feet. We passed through Miraflores Locks in company with the same vessel, dropping another 55 feet to the level of the Pacific Ocean. As the yacht left the lock chamber I felt a thrill, for I realized that at last the water of the Pacific was under her keel, and her name, Pacific Moon, was now justified. No one would be able to point to her and say, “She never got there!”.

We brought up opposite the Balboa Boat Club. Later we went on the blocks alongside the boathouse and got loads of barnacles off the copper of the hull. The harbour-

The Gulf of Panama, and the area outside it, is a medley of adverse currents and calms, and is a baffling place for a sailing vessel. On the afternoon of Easter Sunday, 1932, I was reading in the cabin while John sat on the sun-

This is a peculiar part of the world. We crossed the Equator, but the sky was grey and the sea the colour of lead. For several days the yacht was in the grip of varying currents; and once we saw two meeting, setting up strong ripples. One morning a gigantic swordfish shot up out of the sea and scudded along on its tail, looking at us. Fortunately, the great fish did not think the hull of the Pacific Moon worthy of its sword; I was frightened, as I feared the brute might avenge the fish I have caught in my time. The clouds shut out the sun for several days and prevented us from taking sights. We knew we had gone some miles south of the latitude of Chatham Island, one of the Galapagos, and should be near it. But visibility was bad and, although we watched, we could not see the island. One windless morning the clouds lifted and we saw a great volcano towering into the sky, and we realized that we were drifting past the whole of the group, and that the volcano was on Isabela, an island a good distance west of Chatham. We knew that there was a prospect of water at Wreck Bay, Chatham, and we tried to find some wind to work up in that direction. For two days and a half we struggled with light airs and tried to beat against the set of the current, but all the time we were swept back to the south-

12,000 Miles for £1,000

Finally, realizing that we were using stores and water -

We spent some time in this island and its neighbour, Nukuhiva, and then sailed to the coral island of Takaroa, in the Tuamotu Islands, where we met Victor Berge, the famous pearling master, who was spending a month at his pearling camp on the lagoon. Victor was bound for Tahiti in his small cutter, which was smaller than the Pacific Moon, and we sailed in company into the harbour of Papeete, Tahiti.

Here John found that he had to return home. After making arrangements for his passage in a French vessel, I tried to find a buyer for my yacht. I sold her to a young Argentine, Senor Alfred Guthmann, who did not want the engine, which was removed and installed in another yacht. One night I watched the Pacific Moon sail out of the harbour with Alfred and two shipmates. She touched a reef somewhere near the Tongas but was pulled off and repaired. The two young fellows returned to Tahiti, but Alfred found a native crew and sailed on towards Java. After spending some time in the South Seas I went by steamer to New Zealand and Australia, and then returned to England.

The voyage in the Pacific Moon was one for enjoyment only, no attempts being made at records or spectacular achievements. It was, in the widest sense of the word, a pleasure cruise.

We did the 12,000 odd miles from Dover to Tahiti merely because we were fond of the sport it offered. Many times, especially round the West Indies and Spain, we deviated from our direct course for the simple reason that we wanted to visit or were attracted by some particular port or locality. The expenses of the entire venture were relatively low; from June, 1930, when I visited Oulton Broad, to the time I returned home, over two years later, I spent £1,000.

AT PORT CASTRIES, ST. LUCIA, B.W.I. The author (left) and John W. Johnstone, a Dover yachtsman, his sole companion, after having crossed the Atlantic Ocean. They kept four-

You can read more on “Adventures of the Dream Ship”, “Captain Slocum the Pioneer” and “Gerbault and the Firecrest” on this website.