© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Transatlantic Adventures

The story of three remarkable voyages across the Atlantic Ocean and back by Ahto Walter, a young Estonian, in a sailing boat under thirty feet long

GREAT VOYAGES IN LITTLE SHIPS -

FROM ESTONIA TO AMERICA in a small yacht is a voyage so dangerous that few men would attempt it. Ahto Walter did so on three separate occasions. The first Ahto, as he named his boats, he bought for the equivalent of £15 and reconditioned. She was 29 feet long, with a beam of 9 feet and a draught of 5 ft. 6 in. Ahto’s companion on two of his voyages was Tom Olsen, a young American.

ALTHOUGH the number of men sailing the Seven Seas in small craft grows with every succeeding year, every venture is different, as every sailor varies in Ms methods and his boat. Among the younger generation the personality of an Estonian, Ahto Walter, stands out. His first name is that of the Finnish god of the seas. He likes to get off the beaten track, but when he is on it he welcomes an ocean race with a friendly rival. He does not sail single-

Sometimes he meets bad weather and his sailing companions have to endure much misery, but the boat reaches harbour safely. It is not possible for an ocean-

The story of Ahto Walter’s sea exploits is thus a story of youth, and when we hear the old grumble that youth is soft and that the days of sail are past, it should be remembered that this young man sails small yachts across the Western Ocean in all winds, weathers and seasons. Further, Ahto is a sail-

The father of the Walter family was at one time captain of a Russian steamship that sailed from St. Petersburg -

Outlay Only £15

Ahto Walter read a book by Alain Gerbault in which the French single-

At first he planned to sail single-

This hulk -

Kou, Ahto’s eldest brother, wanted to accompany him. At first this annoyed Ahto and he sailed off with some friends for a week in the rejuvenated boat. When he returned he agreed to ship his brother. They tried to get the Estonian Government interested in the venture, but the President told Ahto he would rather give him a gun so that the boy could shoot himself in his own country and enable his parents to bury him. The Estonian Yacht Club refused to allow them to fly the club burgee, not wishing to encourage “voluntary suicides”, and the harbour authorities at Tallinn refused to issue a certificate that the boat was seaworthy.

Ahto Walter’s high spirits refused to be dampened by salt water, and Kou was as full of pranks as his brother. The first joke was against them. They were boarded at their first port by the smuggler who had sold the boat to Ahto, and he became annoyed when he found they had no drink to sell him. They offered him methylated spirit, which he drank. To their surprise he appeared to enjoy the drink and thanked them for it.

The Ahto I, as the owner called his first boat, was 29 feet long, 9 feet beam and 5 ft. 6 in. draught; she was twenty-

The first storm stove in two panes of the skylight on top of the cabin. Every sea that came aboard sent water into the cabin and soaked everything below: therefore the skylight had to be boarded up. As with most men who go to sea in small boats, the Walter brothers soon discovered that a leak on deck is in some ways as troublesome as a leaky hull. In its progress to the bilge, the sea water spoils everything it touches and thus destroys all comfort in a small cabin.

The first storm stove in two panes of the skylight on top of the cabin. Every sea that came aboard sent water into the cabin and soaked everything below: therefore the skylight had to be boarded up. As with most men who go to sea in small boats, the Walter brothers soon discovered that a leak on deck is in some ways as troublesome as a leaky hull. In its progress to the bilge, the sea water spoils everything it touches and thus destroys all comfort in a small cabin.

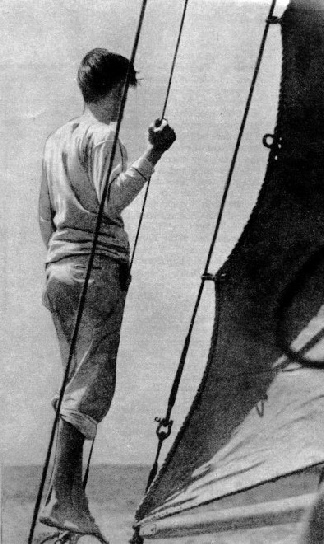

TAKING A SIGHT during Ahto Walter’s long Atlantic crossing. From his earliest years Ahto had been acquiring considerable experience of the sea in the difficult conditions of the Baltic. To him the navigation of a small yacht over thousands of miles of open sea presented no difficulties in good weather.

Their way of solving the dinghy problem, always acute in a small yacht, was to carry a collapsible boat. This was assembled outside Copenhagen. Ahto rowed ashore to buy stores, but as the shops were shut that day, returned with nothing. As the yacht was passing through the Skagerrak to enter the North Sea a storm blew the mainsail away, and the storm-

Off the coast of Holland disaster nearly came in another way. They were becalmed for four days, and at night they slept after having lashed a lantern in the rigging. One night a steamer passed so close that they were rolled out of their bunks by her wash. They put in at Ramsgate (Kent), and the next stage of the cruise was pleasant yachting, for they made friends at every harbour that they entered on the south coast of England. The last port was Torquay (Devonshire), where a leak in the bow was repaired with a canvas patch. The repair was effected when the yacht was beached for scraping and painting the bottom.

By the middle of October all was ready for the first struggle with the Atlantic. In spite of a favourable weather report, local fishermen told them to defer sailing as bad weather was on the way, but the brothers laughed at the warning and sailed for Madeira. They avoided the Bay of Biscay by standing well away, but in the evening of the third day they met the storm that had been foretold.

As the storm increased they shortened sail, until they were reduced to the storm-

The worst of the storm lasted for five days, but two more days passed before the sea subsided sufficiently to enable Kou to mend the rudder. Kou could not swim, but went overboard with a lifeline, while his younger brother stood guard with a knife lashed to a boathook to ward off sharks that were near the boat.

The brothers had no more bad weather except for a squall that knocked the Ahto I on her beam-

Short Rations

After having put in at Madeira, the yacht went to Las Palmas, in the Canaries, where the brothers bought stores for the passage to Miami, Florida. They carried three fifty-

When the discovery was made it was too late to return against the trade wind to Las Palmas, and even if they had done so it is doubtful whether they would have been compensated by the shopkeeper who had sold the provisions.

The Ahto I made a fast passage across the Atlantic for a yacht of her small size, and the brothers sighted the West Indian island of Haiti when they were eighteen days out from Las Palmas. Their luck and the wind then failed. For fifteen days the yacht was becalmed off the north coast of Haiti, sometimes drifting so close to the shore that the brothers could see people working in the fields. There was no harbour, the swell was heavy and the presence of sharks prevented them from trying to land in the flimsy dinghy, which had only a few inches freeboard. During this tedious fortnight they had to halve their rations of a tin of corned beef and half a pound of ship’s biscuit.

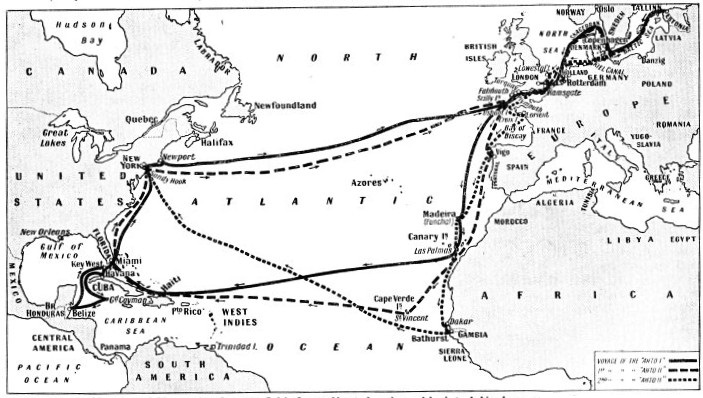

THE THREE VOYAGES of Ahto Walter from the Baltic Sea to North America and back took him by way of the Canary Islands. On the first voyage the Ahto I stood well out of the Bay of Biscay to avoid unnecessary risks, a policy that her owner did not always adopt. The crossings from the Canaries and Cape Verde Islands to the West Indies took advantage of the trade wind.

When the wind arrived it came suddenly out of the north and all but drove the yacht ashore, but they clawed off and reached Miami, Florida, forty-

The four adventurers left Miami on New Year’s Day, 1931, and accepted the offer of a tow out of harbour from an excursion boat, but the tow-

The adventurers had some new experiences in Havana, Cuba. They arrived without clearance papers and disregarded a signal from the quarantine station to stop. The yacht was put under arrest. The British consul intervened, and they were allowed to go ashore, where they had more trouble.

Tragedy Averted

They thought they were being cheated at a cafe, and paid part of the bill in Estonian money, an action that caused a disturbance. The next misadventure was more serious. Ahto Walter and Tom Olsen hired a taxicab and argued about the fare. Ahto struck the driver a blow, and ultimately found himself in a police-

A “norther”, which lasted for five days, damaged the yacht. A sea threw her on her beam ends and another sea filled the mainsail as the boat was lying over and broke the boom, besides carrying away the hatch cover. The yacht had to lie to a sea-

Olsen left the yacht at Grand Cayman (an island south of Cuba), and the three remaining yachtsmen sailed to Belize, capital of British Honduras. Thence they went to Key West and up to New York, where Kou decided to stay. Ahto wanted to enter for the transatlantic yacht race from Newport (Rhode Island) to Plymouth (Devonshire), but his yacht was too small to be accepted. He decided that he would race, nevertheless, to see what she would do.

With Peter Barber as shipmate, he sailed for Plymouth, driving the boat hard. A tragedy was narrowly avoided. Barber, who had not put on his life-

As soon as he had returned to Tallinn, Ahto began looking for another boat. He found one 27 feet overall, 8 ft. 2 in. beam and 6 feet draught. He called her Ahto II, and she proved a drier sea-

As soon as he had returned to Tallinn, Ahto began looking for another boat. He found one 27 feet overall, 8 ft. 2 in. beam and 6 feet draught. He called her Ahto II, and she proved a drier sea-

With his elder brother Uku as crew, Ahto sailed from Tallinn on November 1, 1931, and met a young man at Copenhagen who wanted to join him. The new member of the ship’s company did not stay. He left the yacht at Rotterdam, and his place was taken by Jay, another brother of Ahto. They arrived at Cowes (Isle of Wight) in December, where they met Peter Barber. Barber had bought a cutter called the Enterprise, and was fitting her out for an ocean cruise with two friends. The yachts met a few weeks later at Falmouth (Cornwall), where Uku Walter transferred from the Ahto II to the Enterprise.

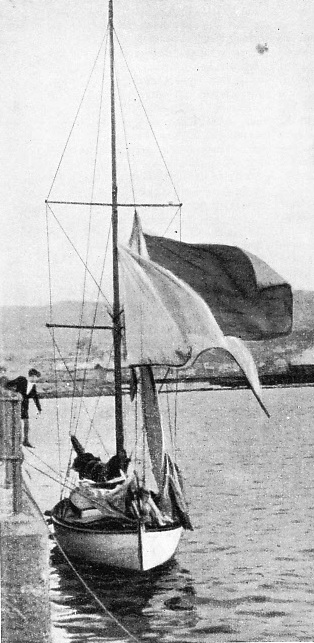

LAND AHEAD. After having sailed for eighteen days across nearly 3,000 miles of open sea from Las Palmas in the Canary Islands, Ahto Walter and his shipmates kept an anxious lookout for the first sight of Haiti in the West Indies. When Haiti was sighted the wind fell and the Ahto I was becalmed for fifteen days within sight of land.

The Ahto II sailed from Falmouth in the middle of January, with a fair wind. Ahto had been told by the Cornish fishermen that bad weather was coming, and before he had gone far he found that they were right. He shortened sail, but did not heave-

They stopped at Vigo in north-

From Miami the yacht cruised to New York, where an Estonian, Verner Sooman, joined them for the passage back to Europe. They sailed in July 1932 and crossed to the Scillies in twenty days from New York, but it took them seventeen more days to reach London. They made the New York to London run without stopping until they moored off Billingsgate. Not liking the smell of fish, they decided to go above Westminster Bridge. They were told that the yacht would clear the bridge but, by the time they reached it, the tide had risen and it was too late to stop. The mast was broken near the top; so they shortened it by six feet and altered the mainsail and the rigging. Despite this jury rig, the yacht sailed the thousand miles to Tallinn in eight days, taking the Kiel Canal route.

Ahto’s brother and the other young Estonian joined the Estonian Navy, and Ahto prepared for yet another voyage. The shortened mast was replaced by one 40 feet high, which was four feet more than the original mast. With Jay’s help, Ahto cut down a young spruce tree on his grandfather’s estate and made the mast. The work pleased him, as he had been asked to pay £30 for a new mast in London. Then he installed a five horse-

Ahto’s brother and the other young Estonian joined the Estonian Navy, and Ahto prepared for yet another voyage. The shortened mast was replaced by one 40 feet high, which was four feet more than the original mast. With Jay’s help, Ahto cut down a young spruce tree on his grandfather’s estate and made the mast. The work pleased him, as he had been asked to pay £30 for a new mast in London. Then he installed a five horse-

Two young journalists asked to sail on the next voyage, and Ahto Walter came to an arrangement with them. He had to wait for Tom Olsen, who sailed in a steamer from the United States, to join him. Olsen arrived, and the yacht sailed towards the end of November in bitterly cold weather, putting in at several places for shelter.

DRYING THE SAILS of the Ahto I alongside a jetty after a wet passage. The sails, on which so much depends, must be stored dry to prevent the formation of mildew. In comparison with the length of the yacht and her low freeboard, the mast is exceptionally high. Ahto Walter prefers to carry extra sail to give the vessel a faster speed when more orthodox yachtsmen would reef.

At Kiel the arms and ammunition in the yacht, intended for use during a hunting trip in Africa, aroused the suspicions of the German authorities. When the four men went ashore they entered, by mistake, a Communist club, where the members thought they were Russians sailing round the world on a propaganda mission. Ahto therefore decided to leave Kiel before matters became complicated. They found the Kiel Canal colder than the Baltic, but at last they reached the North Sea where they had to beat against wind, rain and snow to reach Lowestoft (Suffolk). They spent Christmas Day, 1932, anchored in a fog in the Thames Estuary, and managed to creep up to the Pool on Boxing Day. In the New Year they sailed to the Solent to prepare their little vessel for the difficult passage across the Bay of Biscay.

The Ahto II began the passage well equipped. She had a wireless set, an engine, a lighting set and four strong young men. She was crowded, however, and the weight of the stores made her sluggish. On the first night in the Channel she shipped water over her stern.

Ewald, one of the journalists, suffered from sea-

When the wind became favourable, the Ahto II returned to the Bay of Biscay and more bad weather. Rudy, the other journalist, was not an experienced helmsman, and twice the little yacht broached-

The next ports were Funchal, Madeira, and then Las Palmas, where Ahto intended to replenish stores. Remembering his previous experience with bad food, he took particular care to inspect the goods before he bought them.

Instead of sailing across the Atlantic to America, Ahto turned southwards to the African coast and visited various ports, meeting Peter Barber in his cutter, Enterprise, at Dakar (West Africa). They met again at Bathurst (Gambia), where Rudy found an Estonian steamer in which he sailed for home. Barber enlisted one of this steamship’s crew as a hand to help him sail to America, for he and Ahto intended to race to New York in the two yachts. Before the race they made a hunting trip up the Gambia River in the Ahto II, Bill, the young Estonian seaman, proving an asset.

The race across the Atlantic started from Bathurst, with Sandy Hook as the finishing line. Ahto and Tom, in the Ahto II, reached Sandy Hook in fifty days, four days before Barber and Biil arrived in the Enterprise. During the race the contestants had their share of adventures.

The two yachts left Bathurst, capital of Gambia Colony, on May 17, 1933, on a tropical afternoon, with no one but a few natives to see them off. The heat was almost overpowering as the yachts ran down the Gambia River with the tide. They were glad to leave the river mouth and reach the open sea.

At first the Enterprise took the lead, and at sunset Ahto saw his rival a quarter of a mile off his starboard bow. At noon the following day both vessels hove-

While these repairs were being effected the two yachts exchanged long-

Six days out of Bathurst they ran into a calm, which lasted for two and a half days. The calm was broken by a capricious breeze.

After a final consultation, during which the rivals compared positions and exchanged information, they decided to start the race in real earnest.

The Enterprise went ahead, but she was quickly overhauled by the Ahto II. By nightfall the Estonian yacht was a mile ahead of her adversary. The next morning the Ahto II had left the Enterprise below the horizon.

The Enterprise went ahead, but she was quickly overhauled by the Ahto II. By nightfall the Estonian yacht was a mile ahead of her adversary. The next morning the Ahto II had left the Enterprise below the horizon.

In the ensuing calm both Ahto Walter and Tom Olsen were ill. In addition, Ahto was suffering from a severe toothache. He persuaded Tom to extract the offending tooth with a pair of pliers. The operation took the best part of an hour.

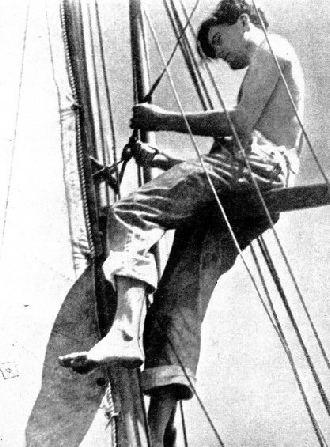

SITTING ASTRIDE THE CROSSTREES, Ahto Walter attends to gear aloft while the yacht is sailing. The helmsman must take especial care to keep his vessel steady or she will gybe. The sail would then swing over and throw the man aloft from his position astride the crosstrees. The success of an Atlantic crossing largely depends upon the yacht’s gear being kept in constant good repair.

Despite the relief afforded by the tooth extraction, Ahto was still feeling poorly, and he found that both Tom and himself had developed high temperatures. They drifted inert during the five days of the calm, and had favourable winds afterwards. It was weeks before they had fully recovered.

In an attempt to discover the cause of their illness, Ahto remembered that he had replenished one of his water-

Squalls and calms alternated. The rain squalls were welcome, as they provided Ahto and Tom with an opportunity of taking shower-

As stated in the chapter ”The Menace of the Derelict”, the Sargasso Sea, besides being a tract of seaweed, is the final resting place of many derelict sailing ships, which have remained there because there is no current to take them out again.

During their enforced idleness, the voyagers at first made up for lost sleep. Then they did various odd jobs in the yacht. Tom Olsen took the radio to pieces and reassembled it, to good effect.

When they entered the Gulf Stream they had to exercise especial care. To take full advantage of the stream’s northward flow, it was necessary to stay in the faster currents. But there was constant danger of squalls, which threatened to carry away the mast.

After forty-

You can read more on “Gerbault and the Firecrest”, “Great Voyages in Little Ships” and

“Supreme Feats of Navigation” on this website.