© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

The Famous “Ariel”

One of the finest ships of her type, the clipper “Ariel” is still remembered for her achievement in the exciting race from China to London in 1866

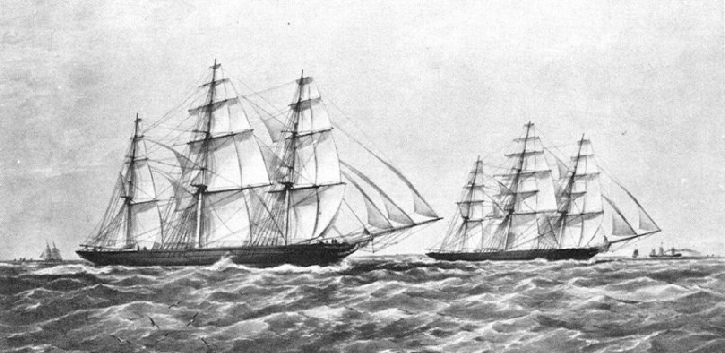

RACING UP THE CHANNEL. A print of two of the most celebrated clippers of the ‘sixties, the Taeping (left) and the Ariel (right). The Ariel, built in 1865, was one of the best known and most extreme of the clippers constructed for the China tea trade. She had a fine reputation while she lasted, but after seven years’ service she vanished with all hands on a voyage to Australia.

THE Ariel was one of the best known of the famous China tea clippers, which were among the most interesting and romantic of all sailing-

The Ariel was built in 1865, a “vintage” year for clippers, by R. Steele and Sons, of Greenock, who had long specialized in the design and building of fast ships. In competition with the original clipper yards at Aberdeen, Steele had fined down the lines until the ships carried so little cargo that they could not pay on any trade except one such as the carriage of tea at high freights. The Ariel was sister, as far as sister ships were possible in sail, to the Sir Lancelot, also built by Steele, the great rivals of her year being the Ada, built by Hall, of Aberdeen, and the Taitsing, built by Connell, of Glasgow.

The first sea-

The British East India Company finally lost its monopoly of the China trade in 1832. There were already many “interlopers”, however, who had to conduct their business under the eyes of the company’s cruisers. Their ships had, therefore, been built for a higher speed than the Indiamen. The private ships which followed the opening of the trade generally had a better speed, but for years the improvement was slight and, charters with intermediate cargo being scarce, few considered more than the single voyage a year. British tea ships, therefore, sheltered as they were by the protection of the Navigation Acts, still merited the description “tea wagons” often applied to them in the ‘thirties and ‘forties. Occasionally the faster American ships visited the China coast, where they attracted attention from the shippers. As these ships were prohibited from carrying tea to England and as the American demand was small, it was not until the Navigation Acts had been repealed that they had an opportunity to influence the trade. This repeal was almost contemporary with the discovery of gold in California and with the birth of the great intercoastal trade, from the Eastern States via Cape Horn. That trade gave the big American clipper its opportunity. Westward to California there was plenty of business and little limit to the prices to be obtained. Going back, however, there was none, and the owners were glad to take their ships across the Pacific in ballast and load them in China with a tea cargo for Britain.

The first American ship to engage in this practice was the Oriental, which appeared on the service in 1850, to the satisfaction of the tea shippers, who were willing to pay double freight to have their tea carried by her. She was soon followed by others that revolutionized the trade; but at the same time another vessel had been built in Britain which had an influence almost equal to that of the tall Yankees.

In 1850 Jardine Matheson built the Stornaway, a smart little vessel of 506 tons. Her design was a compromise between that of the coasting vessels that had really begun the clipper type and that of the opium ships, which had to rely largely on speed for their safety. Principally because of a desire to evade the British system of measurement for tonnage, the Stornaway was much longer, narrower and deeper than her American rivals. Although later modified, this tendency in British design existed for many years.

There was no doubt of the value of speed having been realized. The original Aberdeen design was developed to a high pitch, American ideas being studied carefully and incorporated in it. In her final form, therefore, the China clipper was a compromise reached after much experiment and many expensive failures. She suited perfectly the tea trade, the requirements of which were strict. Size was limited, and there was a strong bias against iron hulls, which, it was believed, spoiled the flavour of the tea, however much dunnage was employed to keep the cases away from the iron sides. Liable to encounter typhoons in China seas, the China clipper possessed seaworthiness of a high order, and, although the weight aloft was limited, everything was of the finest quality and tested to stand a great strain. As freight rates depended on the ship’s reputation for speed and safe delivery, and rose as high as £8 a ton, every precaution was taken.

The noting of the performance of every ship grew into the regular race home with the new season’s tea -

“Dainty Lady of the Sea”

Ships built for speed and driven through any weather were extremely uncomfortable for all on board. There was little passenger trade to modify the speed, as there was on the Australian run. Hands had to live in water for weeks on end, and they received little consideration, the safety of the cargo being the owners’ sole concern. The tea was carried in chests, packed closely with wood and matting dunnage over carefully washed shingle ballast. A tight ship, however, was needed to get it home without damage, and the planking of these small clippers, which were mercilessly driven, generally became soaked and began to leak badly after a few years service. They were then of no further use on the trade. Nearly every season one or more of the ships disappeared without a trace.

The China clipper became the “Dainty Lady of the Sea”, just as the old East Indiaman was the “Aristocrat”. By the ‘sixties of last century the clipper type had attained a high standard, although it was doomed to be driven out of business by the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869. It was at its best in light winds and moderate weather -

The chief responsibility for the design of the Ariel, built two years later, rested with William Steele, Robert Steele’s brother. But as Captain Maxton, who was an experienced China shipmaster, was connected with the owners, he probably insisted on his views being respected.

The firm of Steele had long been known for the fine lines of its clippers, especially in the run aft. In the Ariel this principle was extended farther, so that she was the finest-

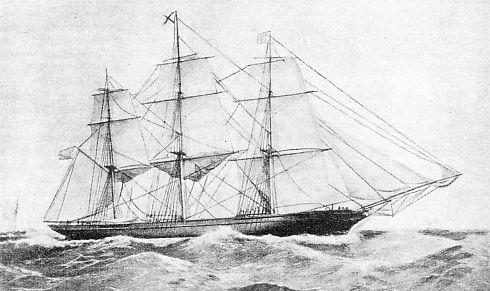

HOVE TO FOR HER PILOT. The Norman Court was generally considered to be the Ariel's nearest rival in appearance, although she was not so extreme in her lines, and she was a safer ship to handle before the wind.

For a tea clipper she was quite a large ship, having a gross tonnage of 1,058 on dimensions 195 feet by 33·9 feet by 21 feet depth of hold. Her carrying capacity was chiefly a matter of stowage, but she was capable of lifting over 1,400 tons on a draught which had to suit Chinese rivers. She was commanded by Captain Keay, a well-

Captain Keay went slowly on the voyage out to China and made a thorough study of his ship. This was important with tender vessels such as clippers, which were often spoiled by wrong handling. The Ariel was particularly difficult to understand, and she had the usual number of early mishaps, mostly aloft, due to minor mistakes or skimped work. But her captain was careful to have them rectified before he had to show his ship’s paces to a critical audience of Eastern merchants. They examined thoroughly all new ships that arrived at Foochow, where £7 a ton was being paid as a freight home, with the customary bonus for a first cargo landed. The Ariel, despite her excessively fine lines and pinched stern, met with general approval.

Captain Keay, who was well experienced, took advantage of the loading facilities. In a short time he had 1,230,900 lb of tea stowed on board the ship, which was the first of the fleet ready to leave, although she had the biggest cargo. At five o’clock on the afternoon of May 28, 1866, the Ariel was towed down to the mouth of the Min River, where she anchored for the night. Early next morning the Fiery Cross, Taeping and Serica also got under way, with the Taitsing only a day behind them. The Ariel’s tug was a poor one, and the Fiery Cross passed her before she bad cleared the river and made a good start. Fog caused more delay, but the time was usefully occupied in moving weights to trim the ship better. It was a popular belief that Captain Keay even filled his cabin with tea chests from the forward end of the hold.

The Race Begins

It was not until just before noon on May 30 that, off the mouth of the river, the Ariel dropped her pilot, having meanwhile been caught up by the Taeping and Serica. A series of minor misfortunes really made the Ariel’s reputation, for the three ships started with less than half an hour dividing them. With such a start, all three captains ran some risk through carrying canvas in weather that scarcely justified it. Within a few hours of leaving the river they had lost sight of one another in rain squalls and mist, although the Ariel was already showing her quality, and by nightfall had considerably lessened the others’ start. The captains knew that the Taitsing would not be far behind, but none of the other ships was sufficiently advanced in her loading to be a dangerous competitor, and from that point onwards each master had to work almost in ignorance.

A China clipper’s master had open to him several minor choices that might make a great difference to her passage, especially in June, when the wind was liable to be uncertain. The passage taken between the islands until Anjer Point (Java) was passed and the open Indian Ocean entered was determined largely by a captain’s local knowledge. Each had his own theories about the channels to be taken and the way in which he should handle his ship. It was as important to be a weather prophet as to be a first-

In 1866 conditions down the China Seas and through the islands were particularly difficult. The first four ships in the race were repeatedly catching glimpses of one another, with the early lead of the Fiery Cross being steadily reduced. This ship, the Ariel and the Taeping passed Anjer Point, the great place for timing, twenty-

Then came the run across the Indian Ocean with the south-

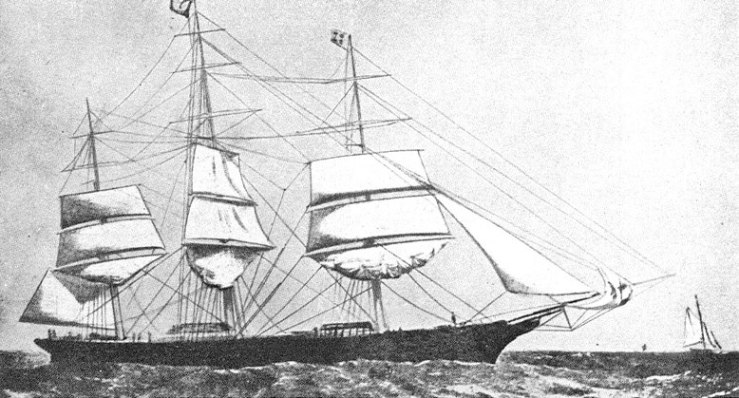

ANOTHER FAMOUS TEA CLIPPER, the Lahloo, This vessel was designed and built by Steele, who was responsible also for the Ariel. The two ships were rivals in the tea trade. The Lahloo was constructed in 1867, two years after the Ariel, but had the older type single topsails.

A number of the reports from various points had already reached home, and as the racing ships began to approach the end of their voyage excitement was intense. They seldom saw one another to exchange signals and sporting greetings, but each hailed every ship that she met for news of the others. At the Cape Verde Islands the Ariel had taken the lead, and on August 12 made her numbers (hoisted her signal flags for the purpose of identification). Next day the Taeping, Fiery Cross and Serica all passed, the last-

At half-

As this race between sailing ships was unique, the subsequent career of the Ariel must seem to be almost an anticlimax. Never-

The opening of the Suez Canal in that year brought an immediate decline in the tea freights, and in 1870 the Ariel was too late for the British market, as she had been detained in Yokohama, for repairs after severe weather damage. In 1871 her time from Shanghai to London was 114 days against the Titania’s ninety-

her out to Australia. The Ariel failed to arrive and her fate is a mystery. What happened to her on that voyage will never be known, though many conjectures have been made. As the year 1872 was a bad season for Antarctic ice, one suggestion is that she hit an iceberg and foundered. On the other hand, there was her proved inability to run before a strong wind with her fine after-

The life of the Ariel was thus only seven years, but during those seven years she made sailing-

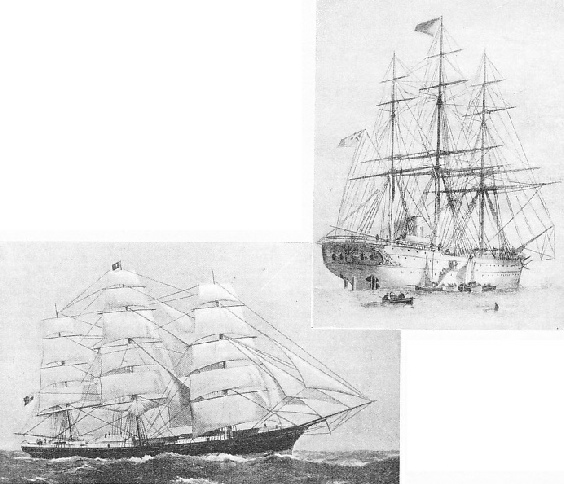

AN EXPERIMENTAL AUXILIARY STEAMER, the Far East was built for the tea trade in the ’sixties, with a full spread of canvas and sufficient steam power to take her through a calm. When under sail, to prevent the screws from impeding the progress of the ship they were lifted into recesses in either quarter of the ship. As with most auxiliary ships of that time, she did not prove a great success.

Another print of the famous but ill-

This colour plate of the Ariel was included with part 1. The artist is not identified, but the plate appears to be taken from “Ariel and the Taeping Tea Race 1866” by Jack Spurling (1926).

THE ARIEL of 1865 was one of the most extreme of the clippers built for the China Tea Trade. She had a length of 195 feet, a beam of 33·9 feet, a depth of 21 feet, and a gross tonnage of 1,058. The vessel was unusually fast in some conditions, but to get this speed her after lines were made so fine that it was dangerous to let her run before the wind in heavy weather. This probably accounted for her disappearance without trace in 1872.

You can read more on “Romance of the Racing Clippers”, “Thermopylae and Cutty Sark” and

“Two Great Racing Rivals” on this website.