The firing of a salvo from a modern warship is an unforgettable experience, overpowering in its effect on the senses and on the imagination. Modern gunnery is so technically perfect that hits can be registered on targets invisible to the naked eye

THE NAVY GOES TO WORK - 12

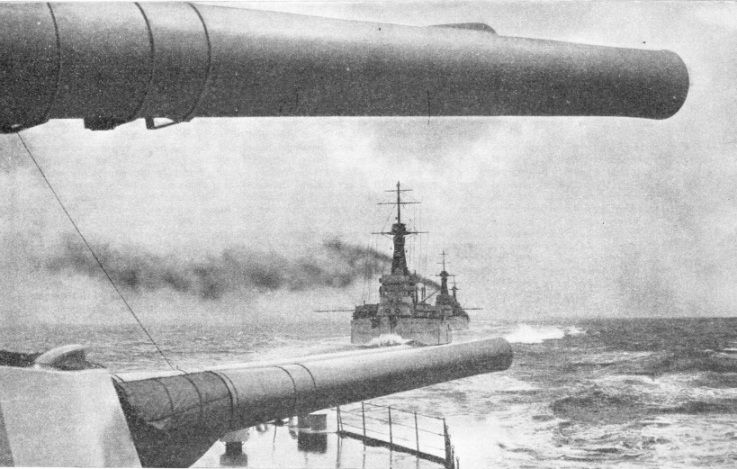

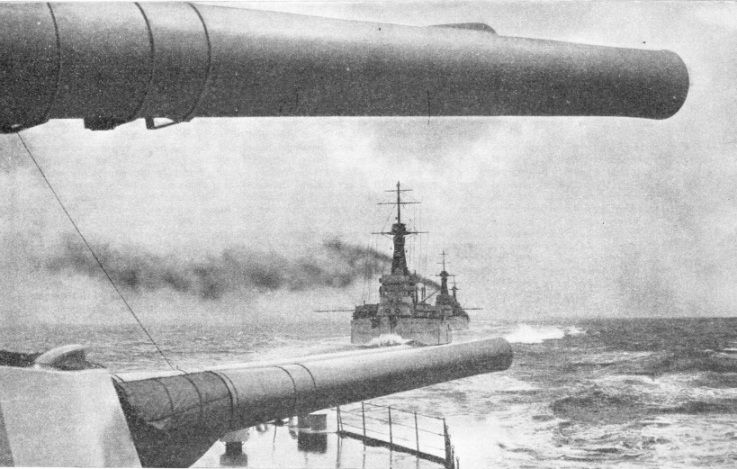

THE GRAND FLEET IN THE NORTH SEA during the war of 1914-18. Framed by the mighty guns of the Queen Elizabeth are the Orion and her consorts astern of their flagship. The Queen Elizabeth, of 31,100 tons displacement, is armed with eight 15-in. 42 calibre and twelve 6-in. 50 calibre guns, in addition to twenty-five smaller pieces and two 21-in. torpedo tubes.

IN every type of man-of-war except the destroyer and the submarine the gun is the principal weapon. It is even debatable whether the gun does not take precedence over the torpedo in the modern destroyer. In contrast to the multiplicity of types and calibres found in the pre-war Navy, the artillery of the present-day fleet comprises only a limited number of types. The heavyweights are the 16-in. and 15-in. guns. The 16-in. type is mounted only in the Nelson and the Rodney, while the 15-in. constitutes the main armaments of all the other thirteen capital ships of the Navy. The ex-battleship Iron Duke, now a gunnery training vessel, carries six 13.5-in. guns.

By the end of 1936 the only intermediate gun was the 8-in., mounted in the thirteen “County” cruisers, the York and the Exeter. The four Hawkins type cruisers are to be rearmed with 6-in. guns, in place of the 7.5-in. model, in accordance with treaty regulations. The 6-in. gun forms the main armament of some thirty-five cruisers and the secondary battery of most of the capital ships. Certain ships also carry 5.5-in. and 5.2 in guns.

The 4.7-in. gun is the standard gun in all post-war destroyers. Older destroyers and many submarines mount the 4-in. gun. Finally, there are the 3-in. piece and several smaller guns of automatic or semi-automatic type. A number of medium and light guns, from 4.7-in. downwards, have been developed as anti-aircraft weapons on mountings which allow for an elevation up to 90 degrees.

Unless and until some other weapon demonstrates its supremacy, the Navy will continue to regard the gun as the decisive arm. It is the principal factor deciding the tonnage of battleships and cruisers, for both categories are essentially floating gun platforms. Monster guns breed monster ships. It was the rise in gun calibre from 12 in. to 15 in. and 16 in. that doubled the size of battleships in little more than fifteen years.

During the war of 1914-18 a gun with a calibre of 18 in. was produced; and Lord Fisher’s “ideal battleship”, to be armed with 20-in. guns, would have approached the 60,000-tons mark. This artificial and futile inflation of calibres, however, was arrested.

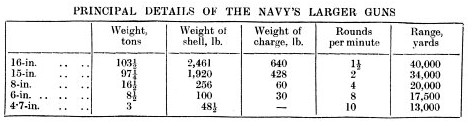

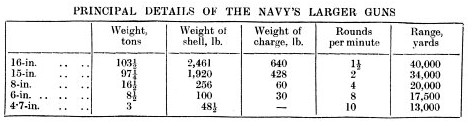

In the table below the principal details of the Navy’s more important guns are set forth.

Guns down to and including the 6-in. are usually twin-mounted in turrets, but the 16-in. guns of the Nelson class and the 6-in. of the Southampton class cruisers are on triple mountings. All the heavy guns, and in certain ships the 6-in. as well, are power-worked. Ammunition is brought up from shell room and magazine, loaded into the gun and rammed home by hydraulic machinery, which also elevates the guns and trains the turret. A modern big-gun turret is a maze of machinery which tends to become ever more complex as new devices for speeding up the rate of fire and improving the control system are introduced.

To obtain the greatest possible muzzle velocity, and therefore the maximum range, accuracy and penetrative power, the modern naval gun is built of remarkable length, this being stated in terms of calibre. Thus, the 16-in. 45 calibre piece is 16 in. by 45 long, or 60 feet, this being the length of the bore excluding the breech-block. The longest gun relative to calibre now mounted in the British Navy is the 8-in. 55 calibre, which has a length of 36 ft. 8 in.

Most British naval guns belong to the “wire-wound” type. Miles of steel wire are wound round the steel chase and the whole length of the gun to give additional strength and localize the effects of a possible burst. Guns of this type are extraordinarily safe but have the drawback of being unduly heavy. In recent years all-steel guns of medium and light calibre have been introduced. They are built up on the auto-frettage system of shrinking an outer jacket over the “A” or inner tube. These new guns are much lighter than those of' the wire-wound type, and appear to give every satisfaction.

When Nelson was approached by an inventor who wished to enlist his interest in a new gun sight which would enable accurate fire to be opened at a range of half a mile, the-great Admiral replied that he hoped always to get so close to the enemy that his gunners could not miss. Completely different are conditions to-day, when target practice is conducted at ranges beyond the vision of the naked eye, and the gunners are trained to hit a swiftly-moving target which may be out of sight over the curve of the horizon. Modern naval gunnery is largely a matter of applied mathematics. It is a highly-developed science with its own corps of specialists, who speak a strange language and spend their days in making abstruse calculations, all connected with the problem of how to hit, and keep on hitting, the target immediately it comes within range. The longer the range at which effective fire can be opened, the better pleased are the gunnery “Jacks”.

Nowadays the guns of practically all ships, down to and including destroyers, are “director controlled”. This means that the guns are laid and discharged by an officer working the director from a central position high up on the foremast or from a lofty tower abaft the bridge. When the director itself is trained on the target its movements are automatically transmitted to pointers on the elevation and deflection dials in the gun turrets. Accordingly, the gunlayer has only to “follow the pointer”, that is, to keep the dial in step with the movements of the pointer, and if that is done efficiently the gun will be kept steadily bearing on the target. As soon as he receives a report that all guns are loaded, the director officer satisfies himself that his sights are correctly adjusted for range and deflection, and then presses a button that closes the firing circuit. In a ship with four twin turrets it is customary to fire four-gun salvos, the right-hand guns in each turret being discharged simultaneously, the left-hand guns following after an interval which depends on the rate at which firing is to be maintained.

IN H.M.S. DREADNOUGHT ten 12-in. guns comprised the most powerful armament in any vessel of her time. She was launched on February 10, 1906, at Portsmouth. A battleship of 17,900 tons load displacement, she had a length of 490 feet, a beam of 82 feet and a mean draught of 26 ft. 6 in. Steam turbines driving four screws gave her a speed of more than 21 knots. The estimated cost of her guns was £113,200.

When “rapid fire” is ordered, as it would be immediately the target is “straddled” (when some projectiles of the previous salvo have pitched over, and others short of, the target), right and left salvos are discharged as quickly as the gunners can load their pieces. The ship’s armament is brought to bear on a moving target at long range by a rather complicated system. The heart of the system is the “transmitting station”, a room situated below the water-line out of the way of possible hits from enemy shells. This room contains the fire-control “table”, an ingenious calculating machine which produces a moving chart, or graph, of the gunnery situation, showing the speed and course of target and firing ship.

Every report which affects gunnery control, such as own ship movements and direction of wind, is at once applied to the table, which modifies its diagram accordingly. As the transmitting station is in constant communication with the director tower, the officer working the director is kept supplied from moment to moment with the data necessary for keeping his sights on the target.

In addition to the fire-control table, the transmitting station contains other instruments, including one which calculates the projectile’s time of flight from gun to target and sets in motion a buzzer at the exact moment when the ship’s own salvos are due to fall. Other instruments indicate when every gun is loaded and ready to fire. The “fall of shot” clock is invaluable when several ships are firing at the same target, for unless each ship were able to identify the splashes of her own salvos effective control would be rendered impossible.

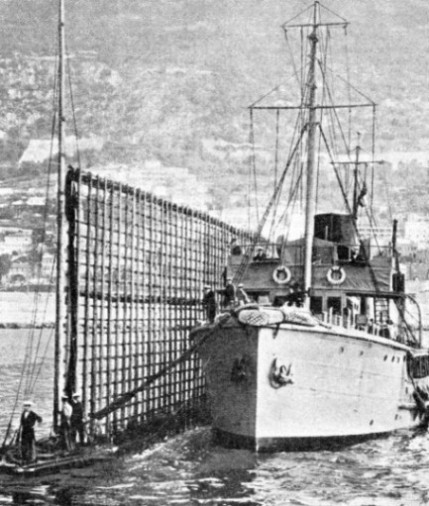

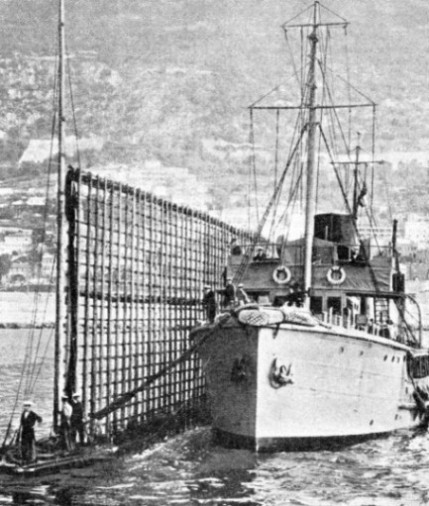

When a battleship is about to engage in long-range battle practice, her decks are deserted, for the guns’ crews are at their posts in turret and battery. The rest of the ship’s company is distributed at action stations and, as far as possible, under cover. A blue flag is bent on to the signal halliards to denote that fire is about to be opened. Far away to starboard a sloop, a fleet tug or a target- towing vessel labours in the swell. Some hundreds of yards astern of her is an object which looks about the size of a playing card. That is the target, a raft supporting a lattice structure covered with canvas.

FIRING A BROADSIDE of nine 16-in. guns from H.M.S. Rodney. The 16-in. guns of the Rodney, as of the Nelson, are on triple mountings and are the heaviest guns used by the Royal Navy The guns have an elevation of 40 deg and a range of 35,000 yards, or about 20 miles. The Rodney, completed in 1927, has a displacement of 33,900 tons, and in addition to her nine 16-in. guns, is armed with twelve 6-in., six 4.7-in. anti-aircraft and twenty-nine smaller guns. She has also two 24.5-in. torpedo tubes.

Immediately below the bridge are the two bow turrets, A and B, trained on the starboard beam, their huge 15-in. guns raised menacingly. Aft, the muzzles of the guns in the stern turrets, X and Y, point in the same direction. Through loudspeakers come the voices of the range-takers, announcing that the target is 19,500 yards distant. At any moment now the permissive order, “Shoot”, may come from the flagship immediately ahead.

Let us presume we are on the bridge. Being in an exposed position, we insert little wads of cotton-wool in our ears as a precaution against gun blast. We are steaming at 16 knots, our signal flags stand out stiffly in the breeze, and away on the horizon we can see through our glasses the target

wallowing and plunging in the wake of the towing vessel. Indistinguishable with the naked eye, the target stands out clearly through high-powered binoculars. The experienced observer always lowers his glasses before a salvo, the concussion of which is liable to drive them against the eyes with painful and possibly serious results.

Now a low buzzing noise is heard. This is the “salvo gong” that sounds a few seconds before the guns fire. Out thunders the first broadside in a sheet of orange flame and tawny smoke. The great ship reels under the tremendous concussion. There is a blast of hot air, as though from a suddenly opened furnace door. The steel casing of the funnel ripples as if it were brown paper, and clouds of dust rise everywhere. From somewhere below comes the tinkle of breaking glass, for every object that is not secured is likely to be flung to the deck.

Meanwhile, the ponderous 15-in. projectiles are speeding on their way, and just as the “fall of shot” indicator emits a warning buzz, four tall, silvery fountains leap out of the sea close to the target and seem to hang motionless for the space of seconds. An instant later the correction, whether “over” or “short”, has been passed to the transmitting station and put on the fire-control table, which automatically makes the requisite adjustment. Thus, before the next salvo is fired the director officer has made the necessary adjustment for range or deflection, which is simultaneously registered on the dials in the gun turrets.

A BATTLE PRACTICE TARGET at Gibraltar. The target is a lattice structure mounted on a raft. Targets are generally towed by a fleet tug of the Saint class. These tugs were built in 1918-19 and have a displacement of 820 tons with a speed of 12 knots. They have a length of 135 feet, a beam of 30 feet and a maximum draught of 14 ft. 6 in.

This time the four left-hand guns roar in unison, and again, after an interval of some forty seconds, the telltale fountains rise about the target, so close as to obscure it in a cloud of spray. From the bridge it looks as if at least one direct hit has been scored, but the spotting officer on the mast reports a “straddle”. This denotes that the exact range and deflection have been found, and the order is given for rapid fire.

Pandemonium follows. Every thirty-five seconds a four-gun salvo crashes out, and before the senses can become attuned to the devastating effects of the noise and concussion of one broadside, the turrets erupt again in flames and cordite smoke. To the novice a full-calibre shoot is a trying experience, but intensely thrilling for all that, and never likely to be forgotten. Frequently, after a few salvos, comes the report, “Direct hit: two projectiles through the target”. Then, when the spray has cleared, our glasses disclose yawning gaps in that canvas structure bobbing in the sea well over ten miles from the ship.

All this time firing ship and target have been moving at high speed on a continually changing course, and the guns have been pointed not at the target itself but at the place where, according to the calculations in the transmitting station, it was likely to be nearly three-quarters of a minute later.

Odd as it may seem, one of the quietest places in the ship during a shoot is inside a turret. As the muzzles of the guns are forty feet outside and a thick armoured shield is interposed between the turret interior and the outer air, the noise of the discharge is muted to a dull thud, and but for the fact that the massive breech recoils two or three feet on its slide one would hardly know that the gun had been fired. On the other hand, a good deal of noise is made by the loading cages which bring shell and powder charges up from below, and by the chain rammer which thrusts them into the breech of the gun.

Immediately after a gun has tired one hears a loud hissing sound. This is caused by a jet of air which is sent through the bore at high pressure to expel the cordite gases and any smouldering fragments from the cartridge bags that may remain in the gun. Otherwise the turret would be filled with noxious fumes and, possibly, scraps of burning silk as soon as the breech was opened.

The most spectacular “shoots” are those in which the target is represented by the radio-controlled battleship Centurion. As she is too valuable to be exposed to the fire of the heaviest guns (15-in. and 16-in.), which would be liable to sink her outright in spite of her massive armour protection, she is reserved as a mark for guns of 8-in. calibre and less.

The Centurion figured in a particularly interesting shoot by the First Cruiser Squadron — four 10,000-tons ships each mounting eight 8-in. guns — on the day after the Silver Jubilee Review of 1935. Having been abandoned by her crew and brought under radio control by her satellite destroyer, the Shikari, the Centurion was sighted at about 16,000 yards steering a zigzag course.

Visibility was fairly good, but there was just enough swell to impart a certain liveliness to the motions of the London, Devonshire, Shropshire and Australia as they steamed in line ahead at 18 to 20 knots. The firing of the whole squadron was controlled from the flagship London. At the appointed time her sides rippled with flame, and a few seconds later came livid flashes from the

three ships astern. Sixteen 8-in. shells were speeding towards the mark, and soon the Centurion was steaming through a forest of flashes.

Salvo after salvo thundered over the sea, and so accurate was the shooting that the battleship appeared to be continually straddled. Every now and then a cloud of dust would shoot up from her decks or topworks, indicating a direct hit, for the shells used for practice are loaded with sand instead of with high explosive.

One hit tore away half the forward funnel casing, others punched holes in the side above the thick armour belt and gashed the decks. Had the shells been “live” the ship would have suffered terrible punishment, for she was hit repeatedly and was at times entirely hidden by splashes. Even as it was the old battleship presented a sorry sight when the firing was over.

For reasons of economy, the expenditure of ammunition in naval gunnery practice is strictly rationed, and no ship is allowed to shoot until her gunnery department has worked up to a high standard of efficiency. This is understandable when it is realized that a three-gun salvo from the Nelson, armed with nine 16-in. guns, costs about £700, and a broadside from a County class cruiser, armed with eight 8-in. guns, costs £408. To save money a great deal of gunnery practice is of the sub-calibre variety.

Novel Gunnery Devices

A tube with a bore of 1 in. or thereabouts is inserted in the big gun and loaded with a miniature projectile and a small charge of cordite. Firing is then conducted exactly as it would be in a full-calibre shoot except that the range is shorter. This “piffing”, as the Navy calls it, affords excellent training for the entire gunnery personnel, and a ship which has done well in sub-calibre firing nearly always distinguishes herself at full battle practice. The chief school of naval gunnery is H.M.S. Excellent, the shore establishment at Whale Island, Portsmouth, where officers and ratings receive a thorough training in every branch of ship’s artillery.

One of the outstanding features of this establishment is a miniature range where young officers are taught to control a big gun shoot just as it would be held at sea. The targets are model ships and the splash of a salvo is most realistically reproduced by a mechanical device. Similar ranges are installed in the gunnery schools at Chatham and Devonport.

At all these schools there are novel methods of instructing rangetakers (ratings who work the big telemeters or rangefinders) and gunlayers. A rangefinder is mounted on a stand which by an ingenious arrangement of cams is made to perform all the motions of a ship rolling and pitching in a seaway. In this way the rangetaker learns to keep his cross-wires bearing on the target in spite of the “heaving deck” beneath his feet.

The development of anti-aircraft gunnery has introduced many new problems into fire control, and this branch of shooting is now receiving close attention in the Navy.

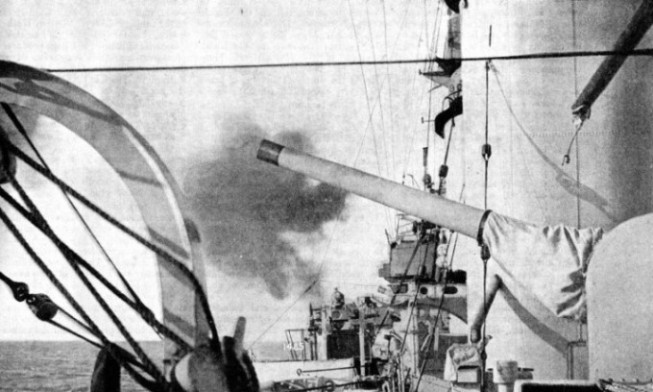

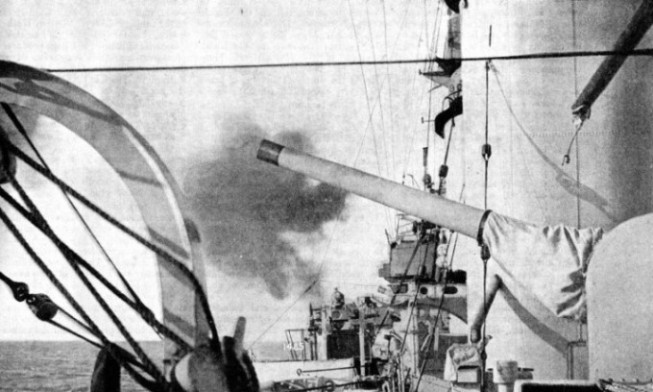

GUNNERY PRACTICE BY THE NEW ZEALAND DIVISION in the Hauraki Gulf, North Island, N.Z. This photograph shows H.M.S. Diomede firing one of her six 6-in. guns. The Diomede is armed with three 4-in. anti-aircraft, sixteen smaller guns and twelve torpedo tubes in addition to her six 6-in. guns. She has an overall length of 472 ft. 6 in., a beam of 46 ft. 6 in. and a mean draught of 14 ft. 3 in.

You can read more on “Battleships and Cruisers”, “Navies of the Dominions” and

“The Ship and the Gun” on this website.