© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Captain Bligh, the Navigator

Cast adrift in a small open boat after the mutiny in 1789 of the Bounty’s crew, Captain Bligh and seventeen out of eighteen men spent forty-

GREAT VOYAGES IN LITTLE SHIPS -

CAPTAIN WILLIAM BLIGH was born in 1754. At the age of sixteen he entered the Royal Navy as an able seaman and won his commission without influence, by ability alone. He became a distinguished navigator and surveyor, and was Master of Cook’s Resolution in Cook's third voyage of exploration. Bligh was Governor of New South Wales in 1805-

IN modern times long boat voyages are made only as a last resource — as the sole plan which offers even a slender chance of saving lives. Such voyages make thrilling reading, for they represent an amount of labour and suffering such as few men have ever been called upon to endure. Of all such tales one stands, and will always stand, head and shoulders above the rest — the story of the famous voyage made by the Bounty’s launch in 1789 from Tofua to Timor, a distance of over 4,000 miles.

The famous Bounty was a small ship (215 tons only) which had been bought by the Navy Board in 1787 for a particular and peculiar service. The famous botanist Sir Joseph Banks had long been urging that an attempt should be made to transplant the Tahitian “breadfruit tree” to the West Indies.

The Bounty was specially fitted to accommodate the breadfruit plants, and carried a crew of forty-

Many hard things have been said, and some of them with truth, about William Bligh, afterwards Vice-

A man who had served with Cook learned, first and foremost, to watch over his men’s health — and everything that is known of Bligh goes to show that he put that lesson into practice. Moreover, he was a fine fighting seaman. His conduct at Copenhagen led Nelson to summon him to the flagship and congratulate him personally. For all this, however, Bligh had several defects which showed themselves plainly as soon as he got his first independent command. He had little control of his temper, and still less of his tongue. He would brook no opposition or remonstrance — and he had an uncanny knack of bringing out the worst side of everyone with whom he came officially in contact.

The Bounty sailed from Spithead on December 23, 1787. Having spent a month in a vain effort to round the Horn, Bligh wore round and made for Tahiti by way of the Cape and Tasmania. Having reached Tahiti in October 1788, he stayed there for six months. The cause of this delay is not clear. Bligh probably wished to make sure of settled weather and fair winds during the homeward voyage. Whatever his reason, he soon had good cause to regret that he had tarried so long. Tahiti then was the sailor's paradise. Its luxuries and its women formed a lure that few could resist or willingly relinquish. Three men had deserted during the ship’s stay, and had been recaptured only with difficulty.

Bligh, who was not on good terms with anyone, had fallen particularly foul, during the six months at Tahiti, of Fletcher Christian, one of the mates. He, finding his life on board unbearable, determined on the evening of April 27, 1789 — the ship being then off Tofua, in the Friendly Islands — to escape ashore on an improvised raft. While taking the morning watch (4 a.m. to 8 a.m.) he hinted at his plan to one or two sympathizers. He formed the audacious project of seizing the ship there and then, by force. Arms were procured and sentries were posted over the sleeping officers. An armed party, headed by Christian, burst into Bligh’s cabin and before the astounded captain of the Bounty was fully aware of what was happening he was pinioned and dragged on deck, in his shirt, to find his ship taken from him.

The largest boat — the launch — was hoisted out, and Christian gave all hands the option of going in her or remaining on board. Eighteen of the men elected for the launch, and were supplied

with a scanty stock of provisions and four cutlasses — but no firearms. Bligh, protesting volubly to the last, was pushed into the boat, still bound, and the tow-

Even in these unprecedented circumstances, Bligh kept his head and what was left of his authority. The Bounty’s launch, 23 feet long by 6 ft. 9 in. beam, was fitted with sail and oars, and was designed to accommodate thirteen men. With the nineteen now in her, she floated so low that her gunwale amidships was no more than 8 in. above the water. On the other hand she was new, well-

At the Mercy of the Natives

Bligh had with him eight officers. In addition, there were Nelson the botanist, Bligh’s clerk Samuel and eight of the hands. As food for these nineteen souls, there were 150 lb. of ship’s biscuits and 32 lb. of salt pork (about enough for five days at normal rations), in addition to 11 gallons of rum, six bottles of wine, 28 gallons of water and four empty kegs. For navigational instruments Bligh had a sextant and John Fryer (Master) an old quadrant. There were no charts, but by a lucky chance a midshipman had brought with him Hamilton Moore’s Navigation and the Requisite Tables, which contained lists giving the positions, by latitude and longitude, of well-

As the mutineers probably intended when keeping the boat so short of food and water, Bligh determined to make first for the nearest island, Tofua, to obtain water and breadfruit, and afterwards to proceed to Tongatabu, the principal island. He was well known to its king, for he had been there with Cook, and could speak the language.

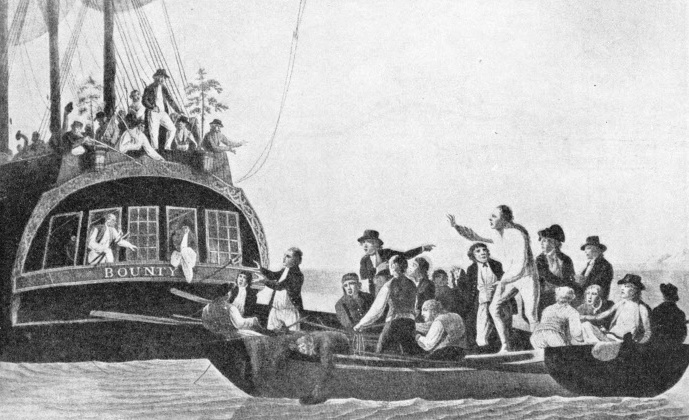

DESTINED TO TRAVEL 4,000 MILES, Captain Bligh and eighteen of the crew of the Bounty were driven by the mutineers into the ship’s largest boat. One of the eighteen men was killed by natives. Designed to accommodate only thirteen men, this launch was 23 feet long, had a beam of 6 ft. 9 in., and was equipped with sail and oars. She was new, well built and a good sea-

Four days spent in collecting a few coconuts and breadfruit on Tofua showed unmistakably that a serious choice of evils confronted them. They had no firearms and the natives were not slow to realize that without firearms the once-

There was no safety for them in any of the Friendly Islands — and it was reasonable to expect that if they landed in any other of the inhabited groups to obtain supplies, their want of firearms would again expose them to the gravest risk of plunder, capture and death. If, on the other hand, they were to abandon any attempt at obtaining further supplies, and to make straight for the nearest civilized settlements — the Dutch East Indies — then, in addition to the grave risk of being shipwrecked, or of foundering in mid-

Bligh divided his crew into watches, and did what he could to get the overloaded boat shipshape. Useless lumber (some ends of rope and a few articles of clothing) was thrown overboard. The carpenter’s chest and tool chest were cleared and used as stowage for the precious stock of biscuit, some of which had already been damaged by salt water. The tools were carefully stowed in the bottom of the boat.

By this time the wind had blown up into a gale, and a high sea was running. On the crests of long ocean rollers the tiny craft was in danger of being blown bodily over, and in the intervening troughs she lay almost becalmed, with her little sail flapping idly. It was only by the exercise of constant vigilance and consummate seamanship that she was kept running before the wind. One slip on the helmsman’s part, and she would either have been “pooped” or have broached to.

On May 4, when they had run something over 100 miles westward from Tofua, an island came into sight ahead, and soon afterwards others.

Discovery of the Fiji Islands

Tasman, in 1643, had sighted a small island on the north-

In the ensuing four days he ran northwestward through the centre of the group — passing, on one occasion, right over a most dangerous sunken reef, with only 4 feet of water covering it. Harassed by trials such as scarcely any navigator before or since has had to endure, Bligh succeeded in producing a chart of his discovery. Considering that it was chiefly made by eye from a small boat with a freeboard of no more than a few inches, the chart is most marvellously accurate. By the evening of May 8, Bligh had cleared the north-

By now they had come to the end of the coconuts and breadfruit obtained at Tofua, and were down to their microscopic rations of biscuits and water. Bligh extemporized a pair of scales out of two coconut shells, and solemnly weighed out each man’s share with a loose pistol-

On May 24 Bligh found himself compelled to reduce the rations still further. Having examined his stores, he found he had enough left, at the present rate of consumption, for twenty-

They were desperately in need of rest. For a fortnight they had been running before a constant succession of fresh gales, being drenched with spray and rain, and constantly obliged to bail for their lives. Cramped and bruised with the constant jerking, soaked through and unable to sleep except in snatches, half-

The one factor telling in their favour, paradoxical though it seemed, was the boisterous, cloudy weather. Had they lain becalmed for a few days under a tropical sun, all on board must have died in agonies of thirst. As it was, they were making good headway westward — 100 miles and more a day. The heavy rain gave their dry throats some relief, and more was obtained by occasionally stripping and soaking their clothes in the sea. Occasionally, too, when the hands seemed more exhausted than usual, Bligh would have recourse to his slender store of spirit, and issue a small tot of rum.

Two more birds were caught and eaten on May 27. At 1 a.m. next morning, breakers being seen close under their lee, Bligh hauled to the northward and waited for daylight. He then ran back towards the reefs, and was up with them by nine o’clock. They formed, as he had conjectured, part of the Great Barrier Reef, discovered by Cook in 1770. A wide and deep channel was sighted, and the boat headed through this to smooth water. Evening saw the men encamped on the shore of an uninhabited island about a mile off the coast of what is now Queensland.

Next morning, refreshed by their first sound sleep in weeks, all hands turned to, half of the party being sent to look for supplies, while the others overhauled the boat. Examination showed that the constant succession of heavy stern-

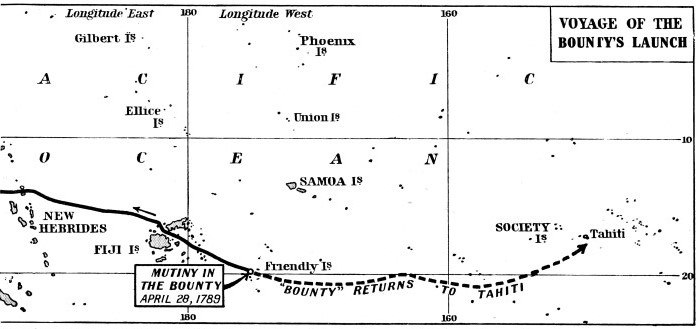

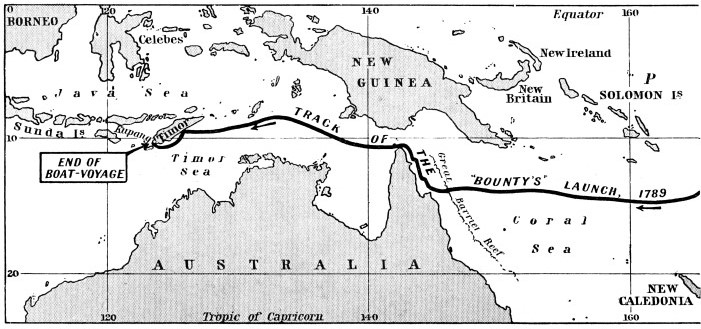

FROM THE FRIENDLY ISLANDS TO TIMOR, a distance of over 4,000 miles, Captain Bligh navigated the

ship's launch after the mutiny in the Bounty in 1789. He made first for Tofua, the nearest island, in the hope of obtaining further supplies, after which he intended to proceed to Tongatabu, the principal island of the group. He discovered, however, that there was no safety for unarmed white men in the Friendly Islands, and eventually decided that his only course was to make for Timor, in the East Indies. He sailed through the Fiji group and was the first man to survey these islands. Bligh was, after Luis Vaez de Torres, the first white man to go through the Torres Strait.

The weather was fine and calm. The island proved able to afford them oysters and fresh water, but nothing else. Bligh had a magnifying glass, and further search of the boat yielded a piece of brimstone and a tinderbox, as well as a copper pot. So all hands dined sumptuously on a hot stew of oysters, biscuit and pork. The island was named, appropriately, Restoration Island, as the day, May 29, 1789, was the anniversary of King Charles II’s return to London.

Bligh gave his men two days’ rest here, and sailed northward on the afternoon of May 30. As he coasted northward, another off-

Eking out her scanty stores with oysters and wild beans whenever possible, but avoiding all contact with the natives, the launch made her way slowly northward along the coast. Most of the party were on the mend except for minor complaints; but Nelson, the botanist, showed symptoms of severe overstrain and sunstroke, and Bligh nursed him carefully, feeding him on an extra allowance of biscuit soaked in wine.

In the afternoon of June 3 they left the Australian coast without regret and headed across the Timor Sea. Bligh had intended to pass, as Cook had done with the Endeavour in 1770, through Endeavour Strait, between Cape York and Prince of Wales Island; but, standing farther northward to clear some off-

The little company of adventurers were back once more to the days of incessant hardship and semi-

The trade wind blew strongly from east-

June 8 was rendered remarkable by the capture of a small dolphin, the first fish which, in spite of constant efforts, they had succeeded in catching. It furnished an additional 3 oz. of fresh food per man, and was worth many times its weight in biscuit — for traces of scurvy were beginning to appear. Moreover, many of the men were “all in” — almost asleep on their feet, and so weak as to be incapable of even the slightest extra exertion. Human nature could endure no more. As even the indomitable Bligh was forced to recognize, their incredible effort was drawing swiftly to its close. The long voyage was almost ended, whether the end were to come in harbour or out on the high seas.

At 3 a.m. on the morning of June 12 new life was suddenly put into the weary little band by the cry of “Land ho!”. Timor was in sight, looming dimly off the port bow. Bligh hauled off until daylight and then, remembering that the Dutch settlement was situated at the south-

In the afternoon of June 13 they rounded the south-

But they were not to fetch Kupang that night. The wind died away at sunset, and although the castaways so far and took to their oars, they made little headway. At 10 p.m. they anchored.

Early next morning they crept slowly into Kupang roadstead under sail and oars and with their colours displayed.

The natives clustering on the beach to scan the new arrival saw the little boat disembark, one by one, what seemed to be a troop of corpses come back from the grave. Their eyes gleamed ravenously out of faces so haggard and drawn that these resembled skulls.

The population of Kupang, high and low, vied with one another in tending and sheltering the men who had come so gallantly. By the afternoon Bligh and his party had been fed, clothed and lodged in a house hired and furnished for them.

So ended the most extraordinary boat voyage ever made. It had lasted forty-

Meanwhile, Fletcher Christian, with the Bounty, had made his way back to Tahiti and sailed thence with eight companions and some natives for an unknown destination — discovered in 1808 to have been Pitcairn Island (25° 03' S„ 130° 06' W.), where the little colony established by the mutineers still survives.

It was Bligh’s misfortune, later in life, when he was Governor of New South Wales (1805-

You can read more on “Instruments of Navigation”, “Supreme Feats of Navigation” and “The Voyages of Captain Cook” on this website.