© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

The Voyages of Captain Cook

This great navigator’s fame rests on his achievements in exploring and charting lands already found rather than on the discovery of new countries. The accuracy and speed with which he carried out his work won for him immediate and world-

SUPREME FEATS OF NAVIGATION -

CAPTAIN JAMES COOK was the supreme navigator-

CAPTAIN JAMES COOK was the supreme navigator-

CAPTAIN JAMES COOK, from the painting by N. Dance, R.A., which is now in the Naval Gallery, Greenwich Hospital. Cook received his commission as post-

His strict attention to detail was extraordinary, and his vision never failed however great the pressure of immediate circumstances may have been. His rectitude and courage inspired the men who sailed with him, and they gave him affection as well as obedience.

Cook did not discover Australia, New Zealand, nor even Tahiti. His work lay in exploring and charting with an accuracy, speed and authenticity that amazed the world and won universal respect for his genius. The French and Spanish Governments, when they were at war with Great Britain, and the rebelling Colonists of North America decided that Captain Cook was to be left unmolested, for all nations benefited by his work.

Cook was born on October 27, 1728, at Marton-

The story that he stole a shilling out of the till and ran away to sea is not true. He did take a South Sea shilling out of the till, but he replaced it with an English shilling, keeping the unusual coin for himself. The grocer, Saunderson, missed the South Sea shilling and questioned Cook, but was convinced that he was not a pilferer. Realizing that the boy was bent on going to sea, the grocer introduced Cook, with his father’s permission, to John Walker, a member of a Whitby collier-

For nearly nine years Cook remained with this firm, rising from apprentice to mate. He was offered command of one of its vessels, but took the surprising step of volunteering for the Royal Navy as a seaman.

According to the pay-

Throughout his career he retained the faith and friendship of those under whom he served. The captain of H.M.S. Eagle was superseded by Captain Hugh Palliser, afterwards Sir Hugh Palliser, Governor of Newfoundland and Controller of the Navy. Palliser became Cook’s patron in later years. Cook experienced some fighting in H.M.S. Eagle, and when he left her after two years was given the rank of master. This rank, now obsolete, was that of a warrant officer. The master was then the navigator.

Cook served in the fleet that was sent to the St. Lawrence River to co-

He returned to England for a short spell and was married to a girl thirteen years his junior, at St. Margaret’s Church, Barking. He was later appointed to survey the Newfoundland coast. During this appointment he carefully observed an eclipse of the sun, and sent his observations to Dr. John Bevis, a famous astronomer who was also a Fellow of the Royal Society. This observation was no part of Cook’s duties; his love of science had prompted him. His report had an important effect on his career, for it attracted the attention of the Royal Society.

Of the three great oceans, the Pacific was then the least known. Distances in that mighty ocean were so vast, and provisioning was so faulty, that the Pacific remained practically unknown for hundreds of years. Except for a few daring Spaniards and Dutchmen, such as Mendana, Quiros, Torres and Abel Tasman, navigators kept to the track first made by the intrepid Magellan. Some men believed in the existence of a vast southern continent suitable for colonization. Among them was Alexander Dalrymple, who had spent many years in the service of the East India Company. Dalrymple had commanded ships and was a surveyor, an astronomer and a Fellow of the Royal Society.

About this time astronomers and navigators were struggling with the problem of longitude. Astronomers were occupied also in measuring the distance of the earth from the sun. The transit of Venus was due on June 3, 1769, and it was calculated that the most suitable observation post would be a point in the South Pacific Ocean that might prove to be on the supposed Great Southern Continent.

As this continent -

Choice of the Right Ship

Cook’s knowledge proved invaluable in the selection of a suitable ship. He urged the Admiralty to reject two vessels that had been suggested and to buy the Endeavour, built at Whitby for the coal-

While she was being fitting out, Wallis arrived back from a voyage of exploration in the Pacific in H.M.S. Dolphin. After his report Tahiti was selected as the site for the observation. Then the Royal Society asked the Admiralty to include Joseph Banks, afterwards Sir Joseph Banks, and his suite, in the Endeavour’s company. Banks brought nine persons with him. He was a young

bachelor who had taken up botany and entomology. He proved a good shipmate, and he and his assistants did valuable work.

The Endeavour sailed to Plymouth for the final preparations, with Cook, now a lieutenant, in command. She sailed from Plymouth on August 25, 1768. with ninety-

At Rio de Janeiro the Portuguese Viceroy proved troublesome. He could not understand the purpose of the voyage and suspected Cook of being a pirate. Cook, however, managed to buy provisions at Rio, which was the last civilized port he touched at on his way round Cape Horn into the Pacific. The Endeavour anchored in Success Bay, at the extreme south-

The scourge of scurvy has been allayed by modern canning, refrigeration and the speed of steamships, but until Cook’s time it was a great menace. Cook insisted on personal cleanliness, and the vessel was kept aired below decks by fires. The anti-

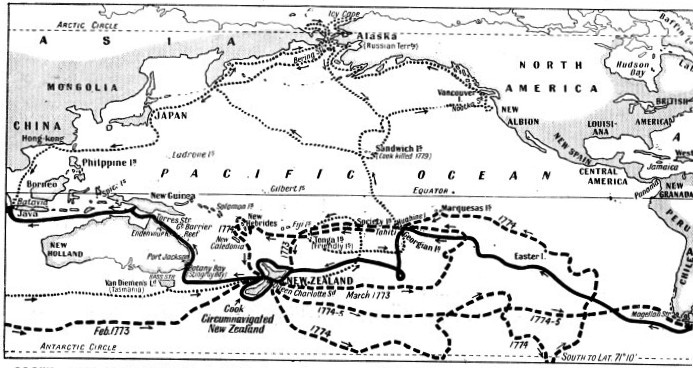

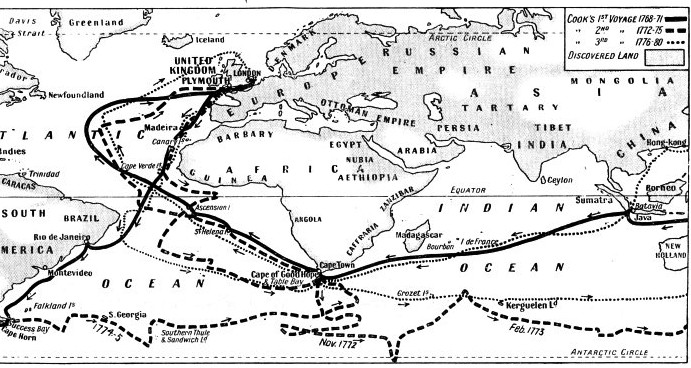

COOK’S THREE GREAT VOYAGES. In 1768 Cook was given command of the Endeavour, which the Royal Society was sending to the Pacific to observe the transit of Venus. On June 3, 1759, this was observed from Tahiti. Cook circumnavigated New Zealand on the return voyage and accurately charted it for the first time. He reached England on June 12, 1771. In the following year Cook was put in command of an expedition to seek for the hypothetical Great Southern Continent, south of the Antarctic Circle. Sailing in the Resolution and accompanied by the Adventure, he explored the Antarctic waters and re-

He used less direct methods to tempt them to the more unusual dishes. The sauerkraut was served to all the officers, and the men were left to decide whether they would eat it or not. Having seen the officers eating it, the men followed suit.

By the time the Endeavour had rounded Cape Horn, crawled slowly across the ocean and anchored, months later, in Matavai Bay, Tahiti, there was scurvy on board.

Matavai Bay, Tahiti, is east of the present harbour and town of Papeete, the capital. Cook knew the temptations the island held for his long-

Venus Point, the northern extremity of Tahiti, where the transit was observed, now has a lighthouse. The point became one of the best determined positions of the Western Hemisphere. Cook surveyed the coast and then sailed to neighbouring islands. He gave the name of the Georgian Islands to the group that includes Tahiti, and named the group to the north-

Cook then began the search for the Great Southern Continent. He sailed over the position where part of it was supposed to exist, and found nothing.

New Zealand Circumnavigated

Cook embarked at Tahiti a Tahitian named Tupia and his servant, and Tupia served as interpreter in the islands. When the Endeavour arrived at New Zealand, Tupia found, to everybody’s delight, that the Maoris could understand his language. Cook, however, found the Maoris different from the Tahitians. They were warlike, and at several places would not talk to the visitors until blood had been shed. When they realized that Cook never tried to take advantage of his superiority in weapons, they became friendly and no treachery was attempted.

Tasman, in 1642, had called the island New Zealand when he had discovered its eastern coast. New Zealand was believed to be part of the Great Southern Continent. Cook circumnavigated and charted the coast in rather more than six months, thus proving that the theorists were wrong.

The Endeavour was prepared for the homeward voyage, and Cook discussed the route with his officers. If he sailed east and round Cape Horn he could make sure that there was no part of the elusive continent in the way; but, because of the time of the year and the condition of the vessel, the wiser plan was to return by way of the Cape of Good Hope. Cook resolved to make for the coast of New Holland, as Australia was then called, and to follow the coast northwards, exploring it on the way.

The northern, western and part of the southern coasts of Australia had been explored by the Dutch, but so little was known of the east coast that Tasmania was thought to be part of Australia. Although Torres in 1606 had sailed through the strait that bears his name, the Spaniards kept the fact a secret until the log of the voyage was found at Manila after the bombardment in 1762. The Dutch believed that New Guinea was part of Australia.

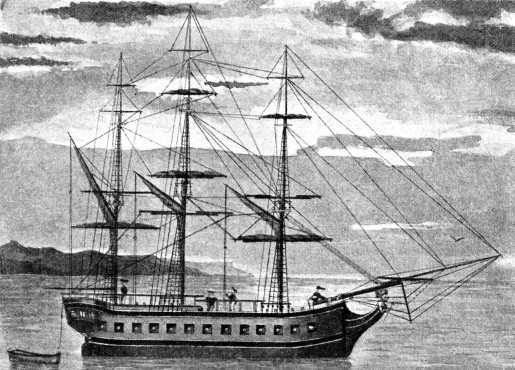

THE RESOLUTION was the three-

Cook sighted the Australian coast at a point north of the strait between it and Tasmania. This strait was afterwards discovered by Bass and bears his name. The first landing was made in a bay at first called Stingray Bay, and later Botany Bay. Banks afterwards recommended Botany Bay as a site for colonization, and Captain Phillip arrived there in 1788 to found the settlement. Phillip moved a little north to Port Jackson, where the great city of Sydney now stands.

Cook landed at various places along the coast in search of a beach where he could clean the ship; but he failed to find a suitable beach. Then the Endeavour stranded on a coral reef. She was holed, but was lightened and refloated. She was beached at the mouth of what is now the Endeavour River, at Cooktown, in Queensland. In a month’s time the repairs were finished.

Having sailed out to what he thought was the open sea, Cook discovered the Great Barrier Reef. It was nightmare navigation and several times the ship was within a few feet of disaster. Cook returned to the mainland and he landed to claim the coast for Great Britain, he sailed through Torres and on to Batavia, where he stopped for repairs and supplies. He sent a copy of his journal and charts to England. He reported to the Admiralty that he had not lost one man through scurvy. Scarcely had he written this report than the malarial climate began its work. Dysentery took a terrible toll. Green, the astronomer, Tupia and his servant, and many officers and men died. Banks barely recovered. After having sailed to the Cape of Good Hope, where a landing was made, the Endeavour anchored in the Downs on July 12, 1771.

Cook was received in London by George III, who made him commander. The Admiralty soon decided to send him out again to prove or disprove the existence of the Southern Continent. Two ships, both built at Whitby, as was the Endeavour, were bought and fitted out. They were the Resolution and the Adventure, of 462 tons and 336 tons respectively. Cook was to sail in the Resolution with Banks; but the accommodation required by Banks and his staff and gear was so great that it hampered the sailing and safety of the vessel. The accommodation was therefore altered. Banks, however, objected to this and with his staff left the vessel.

A German naturalist, John Reinold Forster, who brought his son as secretary and assistant, was appointed in Banks’s place. Forster and his son fell foul of everybody during the voyage; they were full of grievances and complaints and were detested by all. After the voyage, the elder Forster, who engaged a Mr. Sparrman at Capetown to do the work Forster had undertaken, complained that the £4,000 granted to him was inadequate. He said he had been promised the task of writing the history of the voyage, the profits of publication and a post for life, but the Admiralty denied this and forbade his writing anything. Forster evaded this by publishing an account under his son’s name. Part of Cook’s manuscript was used for this account.

The Adventure was in charge of Commander Tobias Furneaux. The two ships left Plymouth on July 13, 1772, and sailed to the Cape of Good Hope. They set out again in November and sailed south to the Antarctic, searching for the continent among the ice. In February 1773 the ships lost one another in gale and fog, but this contingency had been provided for and a rendezvous arranged at Queen Charlotte Sound, New Zealand. Furneaux arrived first and made preparations for wintering, but Cook arrived and ordered him to prepare for sea. Of Cook’s crew only one man had scurvy; but Furneaux’s methods were not as thorough as Cook’s and he had a number of men suffering severely from the disease. Cook’s first task was to secure scurvy grass for the sick men of the Adventure.

Antarctic Ice

The ships sailed next to the lovely island of Tahiti, where Cook renewed former friendships. After the sick men had recuperated, the ships sailed to the Tonga, or Friendly Islands, and thence to New Zealand. They were parted in a storm. After a short stay in New Zealand for provisions, Cook sailed south. Furneaux arrived after Cook had gone, and the two ships did not meet for the rest of the voyage. Cook went as far south as latitude 71 degrees 10 minutes in longitude 106 degrees 54 minutes west, and believed that the ice he saw was the boundary of the Antarctic continent. He was ill for some days, but revived after a diet of fresh meat that was provided by killing a dog belonging to Forster. Cook continued the search for the missing continent, reaching Easter Island and then going north to the Marquesas. These islands had not been visited by white men for nearly 200 years. Having returned to Tahiti to rest the crew, Cook sailed eastwards and re-

This second voyage is considered the greatest of the three, and some hold that is the greatest voyage ever made. No man died of scurvy. Only four men were lost, three by accident and one from disease. The Resolution anchored at Spithead on July 30, 1775, after a voyage of just over three years. The following August, George III sent for Cook and handed him his commission as post-

The third and last voyage was undertaken to verify rumours that a navigable passage connected Hudson Bay with the Pacific Ocean. Cook commanded the Resolution again. Her consort was the Discovery, 229 tons, commanded by Charles Clerke, who had been with Cook on the two previous voyages. At the last moment, when the ships were ready to sail from Plymouth, in 1776, the Discovery had to be left behind. Clerke, who had backed a bill for his brother, was in the Fleet Prison, as he could not pay. There he contracted the consumption that killed him later on the voyage. Cook sailed on July 11. Clerke dodged his creditors and reached Plymouth. The Discovery sailed at the end of the month and met the Resolution in Table Bay. They sailed into the cold south, to Kerguelen Island, to Van Diemen’s Land, now Tasmania, and on to the old anchorage in Queen Charlotte Sound, New Zealand.

Cook had with him a Tahitian, Omai, who had been brought to England by Furneaux in the Adventure. As with Tupia, the native proved of assistance as an interpreter in New Zealand, and he recruited a Maori and a boy in New Zealand to return with him to his home. Cook spent about two months in the Friendly Islands and then went on to the Society group. During this last visit to Tahiti Cook landed Omai at Huahine Island and then sailed for the distant Pacific Coast of North America. On the way he discovered and named the Sandwich Islands. It is not certain whether Cook was the first navigator to reach this Hawaiian group, but he was the first to make them known. Sailing on, he reached Nootka Sound, in Vancouver Island, where he carried out various repairs. Then the two ships sailed up the coast, and rounded the end of the peninsula of Alaska into the Bering Strait. Cook charted parts of the American and Asiatic coasts and then returned to the Hawaiian group.

Stabbed in the Back

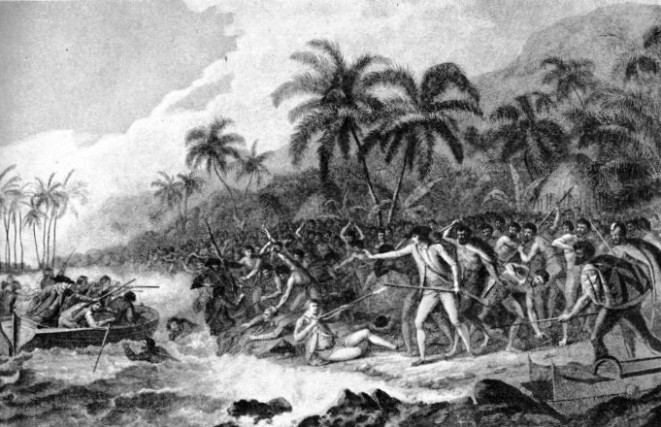

Various incidents culminated in the theft by the natives of the cutter of the Discovery. Cook decided to seize the king or one of the chiefs and to hold him as a hostage for the cutter. He landed with Phillips, the officer in charge of the marines, and with nine marines. The landing party was covered by Lieutenant John Williamson in the Resolution’s launch. Cook went to the king’s hut and was convinced that the king was not concerned in the theft of the cutter. He asked the king and his two young sons to return with him to the Resolution. They were quite willing, but the other chiefs intervened and forced the king to sit down. Cook saw that it would be wise to temporise.

Then the natives received news that men in the cordon of boats which Cook had placed across the bay had fired on some canoes that were trying to escape and had killed a chief. A man threatened Cook with a stone and an iron spike, and Cook fired one barrel of a gun loaded with small shot; but the native used a mat as a shield and was not wounded. Stones were thrown at the marines, and Phillips stunned a chief who tried to stab him. Cook fired the second barrel of his gun, loaded with ball, and killed a native. Under a shower of stones the marines fired a volley; but the natives closed with them before they could reload.

By this time Cook was at the water’s edge. While he was facing the natives they did not strike, but directly he turned he was hit on the head and stabbed in the back. As he fell into the water, natives hacked at him. Four marines were killed, besides Captain Cook, on this day, February 14, 1779.

Under Clerke’s command, the ships sailed north to the Bering Strait, but found no North-

THE DEATH OF CAPTAIN COOK in the Sandwich Islands. After an attempt to discover the North-

You can read more on “First Voyage Round the World”, “Instruments of Navigation” and

“Supreme Feats of Navigation” on this website.