© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Vanishing Coastal Craft

Round the shores of Great Britain there are no fewer than 200 distinct types of coastal craft which are rapidly disappearing before the advent of the modern motor vessels

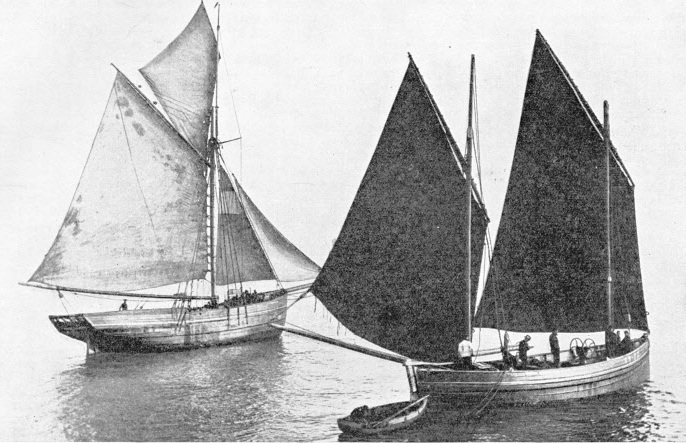

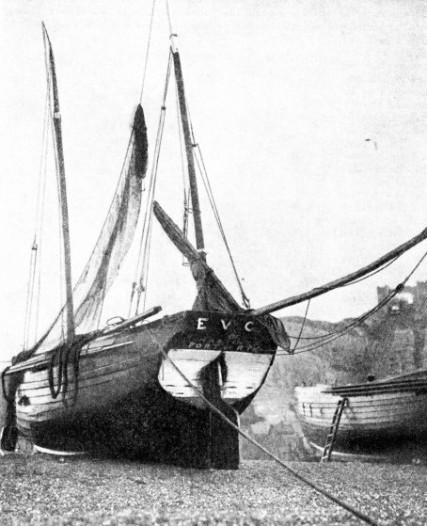

THE MOUNT’S BAY LUGGER, with her characteristic pointed stern, no longer depends on her sails, for all surviving luggers of this type are fitted with engines. Above are shown a lugger at the end of the nineteenth century (right) and an old West-

IN the twentieth century we live in the Age of Power, and we have become accustomed to the rapid advance of modern inventions making sweeping changes in old familiar things. Nowhere, however, have the changes been more devastating or more complete than in the small coastal craft of the British Isles. This has been due, almost entirely, to the invention and development of the marine motor. Whereas a few years ago British coastal waters were alive with the sails of the little fishing boats and coasters, to-

It must be recognized that the days of sail and oar round the coasts of Great Britain are over, as far as commercial craft are concerned. Now that the old types, which have behind them a thousand years and more of seafaring history, are disappearing so rapidly, they are inspiring an interest far greater than they ever did in the days of their prosperity.

On July 22, 1936, an exhibition was opened at the Science Museum, South Kensington, devoted entirely to the old types of British fishing boats. A few years hence, most, if not all, of the craft displayed there will have disappeared.

It is not generally realized that in the British Isles alone there are no fewer than 200 distinct types of coastal craft. Among them are many whose fascinating history can be traced right back to Viking times.

Whatever may be the advantages of the marine motor — and that they are great no man will deny — its introduction has meant the extinction of the older boats. These have either been driven ofi the seas altogether by the new competition or, with cut down sail plans, are being shaken to pieces by thumping engines for which they were never designed. Modern motor craft, with the improvement of communications, have tended to become standardized. The little old-

The old forms of hull, which had been evolved through the centuries by the experience of generation on generation of hardy coastwise mariners, were peculiarly suited to their particular work, and to the beaches or harbours from which they put to sea. But they were not suitable, in most instances, for motor propulsion, where the shape of the boat is governed by other

considerations than those which apply when her movements are controlled by sail and oar. We see to-

In 1934 the Society for Nautical Research, realizing that the fishing and cargo craft were vanishing, appointed a sub-

Big ships were built from plans, which have been preserved. The vessels were commanded by men of education, their log books were written and full records of them were kept by the firms to which they belonged. The position of the coastal craft was different. Built by eye, sometimes from rough wooden models, by men who could do anything with a saw or an adze, but were baffled by a pen, rigged and manned by horny-

The Viking influence is seen most strongly marked all along the east coast of England, and in parts of the English Channel as far west as Portland (Dorset). It is also apparent in the Orkneys and the Shetlands, round the north and west coasts of Scotland, and some way down the Irish Coast, on the east and on the west. Its general characteristic is a double-

Viking or Breton Hulls

The other influence is that of the Breton craft. This extends up the English Channel and into the estuary of the Thames, overlapping the Viking model for some distance. It extends also round into the Bristol Channel, up the west coast of Wales and northwest England, to the Isle of Man and to all coasts of Southern Ireland. Its characteristics are carvel-

Although one or other of these influences may be traced in most coastal craft of the British Isles, that is not to say that the same form of hull or of rig is to be found in every place within the area of the Viking or the Breton type. The essential thing to remember, when studying the developments of British fishing craft, is that the original form of hull was modified by two important considerations. Of these the first was the purpose for which the boat was required. Was she to carry cargo, to fish — and if to fish, then with drift-

Two of the finest, but now extinct, types of beach boats were used for salvage work. In the old days of sailing ships the two greatest roadsteads, where ships lay at anchor, were Yarmouth Roads, and the Downs, off Deal. It is no exaggeration to say that several hundred ships might be seen at anchor at one time waiting for a wind, in either of those places.

If, while they were there, an on-

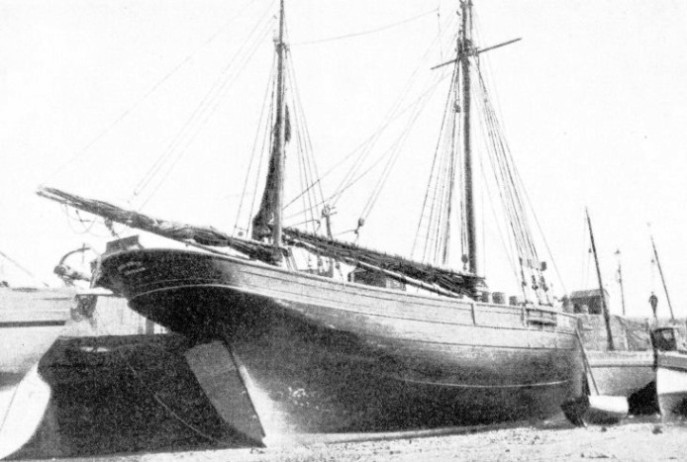

THE BRIXHAM TRAWLER is one of the best-

The boats used for this service on the Norfolk and Suffolk coasts were known as beach yawls. They were the direct descendants of the Viking longships, and were themselves long and narrow craft, adapted for rowing and for sailing. This was because the beach shelved down into shallow water, and the boats were run down and rowed off through the surf, straight out to sea until they were clear of the breakers, when sail would be set.

These craft reached an overall length of no fewer than 60 feet, and with three lug sails, in later years reduced to two, they are said to have attained a speed of 16 knots with the wind abeam. They were the fastest open boats in the world.

The Deal luggers, on the other hand, were boats of much heavier displacement, much more rounded, deeper, of greater beam but shorter, and having a transom stern. They were, however, clinker-

The beach at Deal is extremely steep and the luggers lay on top of it, with their bows pointing downwards towards the sea. If a ship should part her cables and make signals of distress in an on-

The Yorkshire Coble

The master of the lugger watched the sea breaking on the beach, until he saw a “smooth”, which would give him a chance to launch. He then shouted “Let go!”. The chain was slipped, and the lugger, with all the weight of crew and ballast and cables on board, slid with increasing speed down the beach. She took the sea with a mighty crash, but the impetus of her launch sent her out through the first line of breakers, and as she went the sails were hoisted. If things had been timed properly she was already sailing and clawing off shore before the next big sea hit her. If the launch had been badly timed she was thrown back on the beach to be smashed and pounded by the sea, and probably was doomed to lose half her crew by drowning. Yet so powerful were these craft that the weather was never too bad for a lugger, when properly timed, to get off the beach, even in an on-

There were also smaller types called “cats” and first-

Another distinctive type of beach boat, still surviving, fortunately in considerable numbers, is the Yorkshire coble. Although the fact might not be readily recognizable, this boat is a descendant from Viking days. Her shape is unlike that of any other boat in the world. Her bow is high and bold, finished with a knife-

ALONGSIDE THE WHARF AT LOW TIDE. This photograph of the Brixham trawler Vigilance provides an interesting comparison with that of the Revive. The details of the Vigilance’s carvel-

She has no keel proper, but is built upon a ram plank which serves the same purpose. This is similar in shape to a knife on edge at the forward end, and gets broader and flatter farther aft, until it resembles a thick plank laid flat. She is clinker-

When returning to the shore the coble is brought in stern first. When the flat stern lands on the beach, the heavy ram plank takes the shock of beaching. There is no keel to dig into the sand, but the coble slides up, stern first, in the same way as a sledge. To give a grip of the water aft when sailing, the rudder is long and narrow, and projects down underneath the boat similarly to the blade of a partly open penknife. Properly handled, the coble is an exceptionally able sea boat. But the art of coble sailing is so difficult and so unlike anything else that one must be brought up to it from childhood.

Herring Luggers

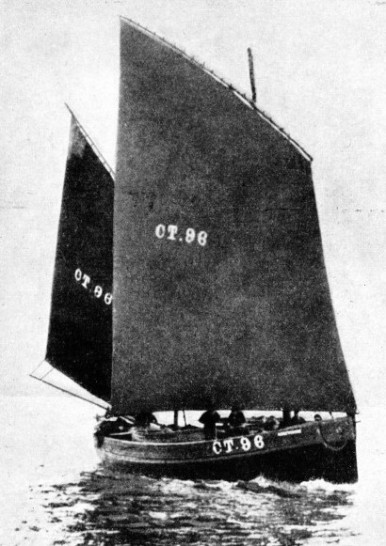

Among other beach boats there are also the fine big Hastings luggers, of which a number still survive with auxiliary motors. They are to-

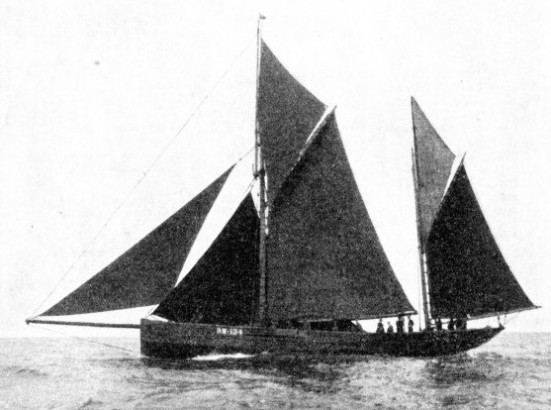

Among the fishing craft that worked from harbours were the herring luggers of Scotland and Cornwall. The Scottish luggers were of three types, all with pointed sterns. First, there were the scaffies. These were comparatively broad, shallow craft, of which the distinctive feature was that stem and stern posts raked at an angle of forty-

The third type was called the Zulu, because the first boat of this kind was launched at the time of the Zulu War (1879). She combined the straight stem of the fifie, which gave that type power and speed to windward, -

SAILING INTO NEWLYN HARBOUR, Cornwall, in a fresh breeze. The Isabella is a two-

The luggers of Cornwall are of two types, the east Cornish and the west Cornish. East of the Lizard the square transom stern is in general use. West of the Lizard the pointed stern is the common type. Both types are rigged with lug sails, a big dipping-

The reason for the sharp stern being found west of the Lizard is that the harbours there were small, artificial and drying. It was therefore necessary to fit as many craft as possible into a small space. If a tin of sardines is opened, it is clearly seen that if they had been designed with transom sterns, it would not have been possible to get as many of the fish into a tin.

Another reason is that with a pointed stern, the planks are laid edge to edge, one above the other on the stern post. When a big swell runs into the harbour as the tide falls, this form of building is less liable to suffer damage from bumping on the hard bottom than when the planks are splayed outward as in transom-

Many other types of fishing craft are rapidly disappearing. The Yarmouth sailing drifters have completely gone. Of 300 Brixham trawlers existing immediately after the war of 1914 18, fewer than a dozen first-

The Thames bawleys and the Whitstable and Colchester oyster smacks are being replaced, when they are replaced at all, by modern motor craft. The passing of the deep-

THE MANX “NICKIE” is a carvel-

The tale can be continued indefinitely. But for the efforts now being made to preserve them historically, these interesting types might vanish, leaving no trace behind them but their name. As with the beach boats and fishing craft, so with the sailing coasters, dealt with in the chapter “Romantic Sailing Coasters”. The introduction of modern small motor-

The Humber keels are the only purely square-

Viking descent, even to the name; for it was in three ceolas that Hengist and Horsa were said to have landed to found the kingdom of Kent in A.D. 449.

The keels are double-

In 1822 a vessel was discovered under the bed of the River Rother in Romney Marsh, Kent. She cannot have been dated later than 1287, when the course of that river was changed in a great storm. The shape, construction and apparent rig of this craft were exactly those of the modern Humber keel, and her dimensions coincided within a few inches in length, beam and depth.

11th Century Survival

It is often said that the Humber keel of to-

The billyboy was the more modern development of the Humber keel for sea-

The schooners and ketches are also disappearing because they cannot compete with the modern motor coaster. And even the Thames barge is slowly being driven off the sea. The days of coastwise sail are over.

The schooners and ketches are also disappearing because they cannot compete with the modern motor coaster. And even the Thames barge is slowly being driven off the sea. The days of coastwise sail are over.

THE HASTINGS LUGGER is remarkable for her peculiar old-

You can read more on

“Romantic Sailing Coasters” and “Thames Sailing Barges”

on this website.