© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

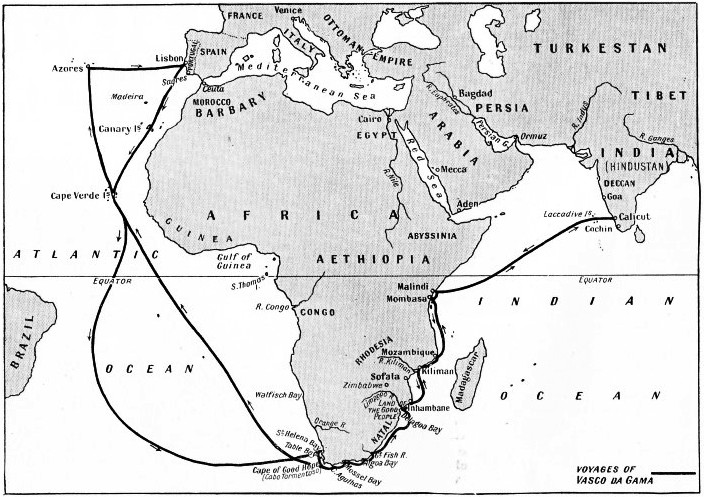

Voyages of Vasco da Gama

Six years after Christopher Columbus had sailed across the unknown Atlantic, Vasco da Gama, another great navigator, discovered the sea route to India by way of the Cape of Good Hope

SUPREME FEATS OF NAVIGATION -

AN ANCIENT PORTUGUESE FORT at Mombasa on the east coast of Africa. This fort, now known as Fort Jesus, is on the spot reached by Vasco da Gama on Palm Sunday, 1498, under the guidance of two Arab pilots.

AFTER he had sailed from Portugal with four ships in July 1497, Vasco da Gama discovered the sea route to India by way of the Cape of Good Hope. He was one of the greatest navigators of the fifteenth century -

Portugal did not build up her overseas empire by supporting a man obsessed with one idea, as Spain had supported Columbus. Portugal’s empire was the fruit of the study and enterprise of Prince Henry the Navigator. Born in 1394, nearly a hundred years before Columbus discovered America, Prince Henry was the younger son of King John I of Portugal, whom he helped in freeing Portugal from the Moors.

It is not known whether Prince Henry’s ambition was to find a way by sea into the heart of Africa to reach the fabled land of Prester John and gain his aid in breaking the power of the Mohammedans, or whether he intended to discover a way round Africa to reach India. In those days the Mohammedans controlled the overland route to India, and their galleys and pirate vessels harried all commerce in the Mediterranean. Prince Henry founded a school of navigation at Sagres, near Cape St. Vincent in Portugal, and sent out numerous ships south along the coast of Africa, braving the “Green Sea of Darkness” and its terrors.

Prince Henry died in 1460, but his work went on, and every Christian who was interested in discovery, astronomy, or map-

About eleven years after the prince’s death the equator was passed. The River Congo was found by Diego Cam, who later sailed almost to Walvis Bay, on the south-

Other explorers had been sent overland to Africa and India, and one of them, Pedro de Covilhao, a Jew, reached Aden by way of Egypt and the Red Sea, and took ship from Aden to Calicut and Goa, south of Bombay, in an Arab vessel. He went back to Africa and journeyed down the east coast. He heard rumours of Madagascar, and in his reports home he stated that ships sailing down the west coast of Africa could be sure of reaching the extremity of the continent.

Piecing together various similar reports, King John II confidently altered the name of the stormy cape to “Cape of Good Hope”.

When Diaz returned in 1488, progress was delayed by the war with Spain and the subsequent death of King John II. King Manoel, who came to the throne in 1495, determined to complete the search, in the hope that he could divert the trade in spices which had enriched Venice and other cities of Italy. In those days spices were used to preserve and to make food palatable when the flavour needed disguising. King Manoel appointed Vasco da Gama to command the new expedition.

Vasco da Gama was then aged about thirty-

4,500 Miles in Four Months

Over and above their pay of about twelve shillings a week, da Gama gave an extra five shillings a week to those who learned to be rope-

The sailing of the ships in July 1497 was a great occasion. Da Gama and his captains kept vigil all night in the chapel of Belem, which Prince Henry had built for his mariners near Lisbon. On July 8 the ships set sail, accompanied at first by a caravel commanded by Diaz, who was bound elsewhere. They made south to the Cape Verde Islands, where they took in more

provisions and water and sailed again on August 3.

It was after he had left the Cape Verde Islands that da Gama proved his seamanship. Instead of crawling along the coast into the Gulf of Guinea with its baffling winds and calms, he kept south, pushing into the unknown. At one time he must have been within a few hundred miles of the coast of Brazil. In later days ships often went within sight of Brazil to pick up a good wind to take them round the Cape of Good Hope.

Not until November was the South African coast sighted. Every vessel flew her bunting, and the crews put on their best clothes and fired guns to celebrate. On November 7, when the vessels anchored in St. Helena Bay, north of what is now Capetown, they had been at sea over four months and had sailed 4,500 miles. Columbus had only sailed 2,600 miles between the Canaries and the West Indies.

THE DIRECT SEA-

Da Gama sailed round the Cape of Good Hope, punching into a head wind, and brought up in Mossel Bay, where he transferred all stores from the storeship and broke her up. He traded bells and red caps with the Hottentot natives for ivory armlets and an ox, and relations were so amiable that the Hottentots played reed pipes and danced. A squabble, however, followed, and guns were fired until the natives fled. Continuing his voyage, da Gama passed the farthest landmark Diaz had seen, and had to battle with head winds and the strong adverse current which sometimes set the ships back. On Christmas Day they were in sight of land, which da Gama called Natal in honour of the day. In the hope that he would be able to get out of the Agulhas current, da Gama headed away from the shore, but he ran short of water and had to return to land, anchoring in the estuary of the Limpopo River.

So friendly were the Bantu tribesmen that da Gama called the country the “Land of the Good People”. The “Good People” were armed with longbows and arrows, iron-

Da Gama noticed that the natives wore copper ornaments, and for this reason he called the Limpopo the “River of Copper”. Centuries later millions of pounds were spent and great railways were built to get that copper out of the heart of Africa. On January 16, 1498, Da Gama set sail again. His next anchorage was in the estuary of the Kiliman River, which he named the “River of Good Tokens”, because he found signs of civilization there.

More than a month passed here, and a broken mast in Paolo’s ship was repaired. The crew, meanwhile, had a chance of recovering from the scurvy that had attacked all three ships. This is the first recorded instance in history of ships’ crews suffering from scurvy. The disease is attributed to an excess of salted food, and no remedy was found until the days of Captain Cook, whose voyages are described in the chapter “The Voyages of Captain Cook”.

Wealth of India

When the men had recovered, da Gama set sail and reached Mozambique on March 2. There he learnt that the four ocean-

With two Arab pilots on board, the ships reached Mombasa on Palm Sunday. The next port of call was Malindi, a little further north, but the Christians were now in Mohammedan country, and da Gama decided to leave the coast He set sail for India, with an Indian to act as pilot.

With the south-

Wary of venturing into the port where he would be at the mercy of the Hindu ruler, the Zamorin, or Raja, da Gama berthed outside the port. The monsoon was at its height and made their position uncomfortable. The Zamorin sent a pilot to take the ships to a safe anchorage some miles away, and granted da Gama’s request for an audience. The Zamorin was in a difficult position. He was a Hindu ruler of a city of Hindu merchants and traders, but the maritime trade was in the hands of the Moplas, who were Mohammedans descended from Arabs.

Although the Zamorin was anxious not to offend them by favouring the strangers, he had to maintain Calicut as a free port. Da Gama landed with thirteen comrades and started for the Zamorin’s palace outside the city.

The ruler received da Gama courteously, and the Portuguese were impressed by a golden spittoon and a huge golden bowl that contained the betel nut the ruler chewed. Next day when two officers of his court inspected the presents the King of Portugal had sent to their royal master, they did not conceal their disdain. The gifts were wash-

Da Gama landed some of his goods but failed to find buyers at Pandarani, where he was lying. The Moslem traders laughed at his merchandise and called it rubbish. He complained to the ruler, who first sent an agent to help him and then had the goods sent to Calicut, where they were stored in charge of a party of Portuguese sailors. Having decided to sail home, da Gama sent a gift to the Zamorin and asked for some spices for King Manoel. The reply was a request from the Zamorin’s factor for payment of customs duty on the goods that had been landed, and a guard was set over the Portuguese sailors. Da Gama promptly seized a number of Hindus and sailed to Calicut, where he anchored. Negotiations were opened and the Portuguese hostages and some of the goods were restored, while da Gama released all his captives except five.

On August 29 the vessels sailed for home. The passage to Portugal was an ordeal. Scurvy was again prevalent and when the three ships arrived at Malindi, on January 7, 1499, only about half a dozen men were fit to work each ship. After having left Malindi, where more men died in harbour, da Gama decided on the drastic step of taking the men off the Sao Raphael and burning her. This gave the survivors a better chance, and the two remaining vessels passed the Cape of Good Hope.

The long voyage in the Atlantic was misery, with the ships hampered by sick men. The two vessels parted. The Berrio arrived at Lisbon in July, while the Sao Gabriel put in at the Azores, where da Gama’s brother Paolo died of consumption. After he had buried his brother da Gama reached Lisbon in September, after a voyage of more than two years. Only fifty-

Fierce Reprisals

Six months later, in March 1500, thirteen ships sailed from the River Tagus under Pedro Alvares Cabral, who was accompanied by Bartholomew Diaz. The vessels stood right out into the Atlantic as da Gama’s had done, and discovered Brazil. Near the Cape of Good Hope a tornado sank four vessels with all hands. Bartholomew Diaz was drowned, but Cabral reached Calicut in September and founded a factory there. This caused trouble with the Moslems, who stormed the place and killed all the occupants. Cabral bombarded Calicut, and sailed to Cochin, farther south along the coast. There he successfully founded another factory. He returned to Lisbon in July 1501 with a cargo of pepper which yielded a handsome profit. Vasco da Gama set sail from Lisbon on his second voyage in February 1502 with a large fleet. He arrived at Calicut in October.

When the Zamorin saw the fleet he hastened to send offers of peace, remembering the damage the town had received from Cabral. Da Gama was no longer a weather-

After his return in September 1503, da Gama settled down to enjoy his rewards. Twenty-

As early as 1505 King Manoel had decided that to maintain order in his Indian possessions it would be necessary to establish the office of Viceroy. He sent out Don Francisco de Almeida as the first Viceroy in that year. The most famous of the Viceroys was Alfonso de Albuquerque. After a turbulent term of office Albuquerque died at Goa in 1524.

Vasco de Gama was chosen as his successor. The position was not an enviable one. A condition of constant warfare existed in the Indian possessions and the dangers of contracting disease were great. Stern measures were necessary to maintain order in the hard-

Although da Gama was then sixty-

His term of office was brief, however, for he fell ill and died on Christmas Eve, 1524.

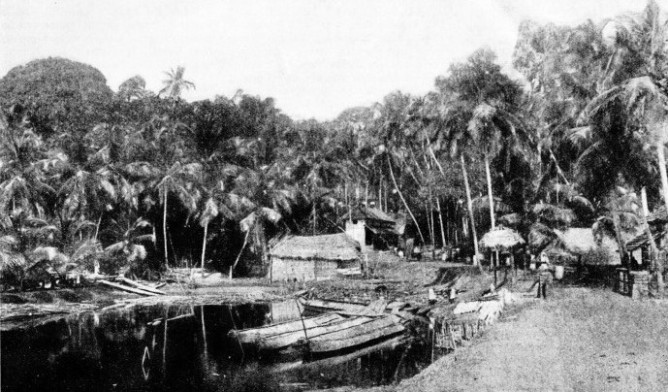

THE LANDING-

You can read more on “The Discovery of America”, “Instruments of Navigation” and

“The Voyages of Captain Cook” on this website.