© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Man’s Conquest of the Depths

Attempts to overcome the dangers of diving have been made from the earliest times, and there have been many primitive types of diving suit, but it is only in the last hundred years that developments have enabled men to work in safety at great depths

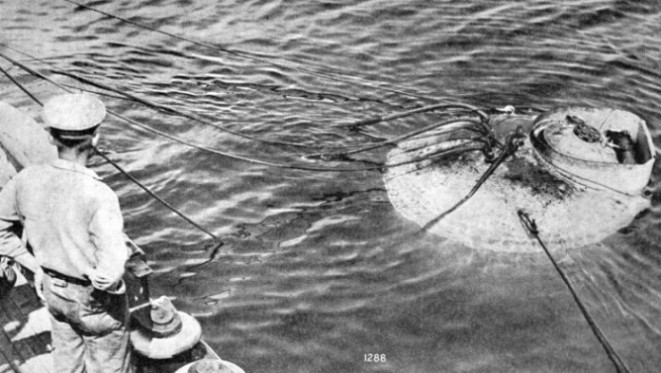

PREPARING FOR DIVING OPERATIONS from the United States salvage vessel Falcon, of about 1,250 tons, during work on the sunken submarine S 51. The Falcon once had an unusual task off the New Jersey coast when attempting to locate the United States Navy dirigible Akron, which had crashed into the sea. The modern diving dress, as universally used today, is based on the principle invented by Augustus Siebe in 1837.

SUCH wonders of salvage as the raising of sunken battleships or the recovery of gold from liners many fathoms below the surface of the sea are epic stories of the achievements of science. The science of salvage is comparatively new, although its origin lies in the mists of antiquity, for diving in some form or other has been carried on for as long as history records.

Modern diving has reached such a pitch of perfection that hundreds of men every day work under the water in safety. Other modern wonders such as radio, television and air-

The modern harbour works that are among the greatest of all engineering achievements, as, for instance, the great quays at Southampton where the ocean greyhounds berth, owe much to the diver who works on the underwater portions. The walls of the quays and docks have to be cleaned and repaired by divers, and new timbers have to be fitted to piers and lock gates. In Liverpool, for example, a diver inspects the underwater portions of the dock walls every day.

In many other directions the assistance of a diver is invaluable. Divers examine the piers of bridges and report on the condition of river walls. They have, for example, assisted in the building of a sewer extension at Whitley Bay, Northumberland, and in the laying of an electric cable across the River Tay at Abernethy, Perthshire. Similar work is always in progress all over the world.

This everyday work of diving is as important to ordinary life as the raising of any wreck, although it may not be as spectacular as the work of the divers who have rescued men trapped in sunken submarines.

The present advanced state of the science of salvage and diving has come about only by the slow development of the diving dress through the ages. The modern diver has the use of inventions and accessories that were never dreamed of by the diver of old. Among such up-

Even the comfort of the diver has been studied to a marked degree. It is now possible to supply him with warmed air, a wonderful aid when working in freezing water.

The warm air is supplied through torpedo-

Another recent addition to diving equipment is the tightly fitting telephone disk, worn over the ears inside the woollen skull caps. Leg fittings are now more tightly laced to prevent the accumulation of cold air. and the diver’s gloves are cased in armoured rubber. Perhaps the most welcome addition of all is the steel chamber, fitted with an air lock, in which the diver can descend to the bed of the sea and from this retreat emerge into the open to do his work. This chamber is fitted with a telephone and is electrically lit and heated.

Electrical appliances of many kinds are now used by divers as a matter of course. It is no novelty for them to ride on the ocean bed in an electrically driven submarine tractor weighing 18 tons and moving on caterpillar trucks. The diver can blast rocks in the depths as easily as is done on dry land, and use a pneumatic drill as effectively as the labourer working in the roadway. The diver can cut a hole through steel with a hydro-

Yet without these modern appliances and inventions, diving has been an important trade from time immemorial. The existence of mother-

In Greek times, however, diving was a science. Some sort of apparatus must have been used, for the divers were almost an adjunct of the Athenian Navy.

When the Athenians besieged Syracuse in 414 B.C. it was their divers who smashed the harbour defences, and the length of time they needed to stay under water to do their work is ample proof that they wore some sort of respirator.

Thucydides, the Greek historian, in his description of the siege, says, “There was some skirmishing in the harbour about the palisades which the Syracusans had fixed in the sea in front of their old dock-

“The Athenians brought up a ship, of about 250 tons burden, and bulwarks, and from their boats they tied cords to the stakes and wrenched and tore them up, or dived and sawed them through underneath the water. Meanwhile the Syracusans kept up a shower of missiles from the dock-

The earliest diver to be mentioned by name would appear to be a Greek called Scyllis, who was employed by Xerxes in 481 B.C. to recover treasure from some wrecked Persian vessels. In A.D. 77 the Rhodians were doing such a thriving business recovering valuables from sunken ships that it was considered a sufficiently important matter to require a law to establish the rights of the respective parties. The law enacted that divers must be guaranteed a share of all they brought up from the sea, the share varying according to the depth of the dive. This much and no more were they permitted to claim from the owners. A similar law exists to-

An Arab diver of the twelfth century, according to Bohaddin, the Arabian writer, used an appliance for breathing under water which he called a “bellows”. The only other record of bellows appearing among diving equipment relates to Drieberg’s comical outfit which he called “The Triton”. He offered it to a ridiculing public in 1808. It was never used because it was so monstrously absurd. The main feature was a pair of bellows, carried on the back and worked by the diver jerking his head backwards and forwards. It was hardly a serious contribution to the solution of a serious problem.

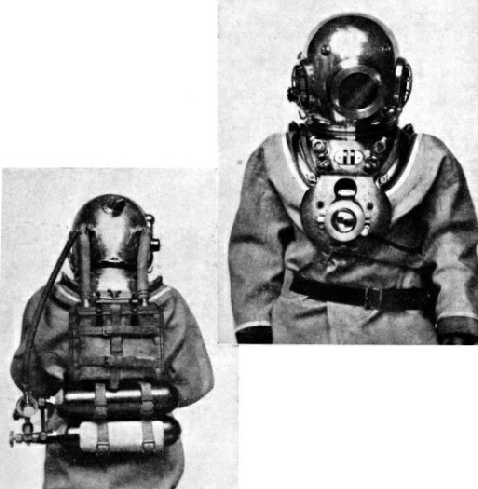

MODERN DIVING SUITS are equipped with many accessories that were undreamed of until a few years ago. For instance, in the front weight of the diver (shown in the right hand photograph) is a compact electric lamp which is supplied with current from a battery. The photograph on the left shows two cylinders containing oxygen and air, and the metal chamber, strapped on the back, which contains a special carbon dioxide absorbent. The diver breathes the mixture of air and oxygen and his exhaled breath passes through two tubes into the absorbent chamber.

In the year 1405 a German inventor introduced what he described as “a dress for working under water”. The dress consisted of a leather jacket and a metal helmet with two glass windows. A feature of this equipment was that jacket and helmet were lined with sponge, which was supposed to retain air. A leather pipe sprouted from the top of the helmet and this pipe was connected up to an air bag which was arranged to float on the surface of the water. Many of the designs which accompanied Leonardo da Vinci’s notes, published about 1510, were designs for diving appliances, but there is no evidence that they were created in wearable material. One drawing shows a diver with his head in a helmet from which sprouted spikes, facetiously said to be there to protect him against fish. Sandbagged boots appear on another figure — forerunners, in artistry or reality, of the modern lead-

The next practical advance in the conquest of the deep came somewhere about 1538. The invention was really the first apparatus with sufficient scientific detail in its construction to warrant its claim to the appellation of the first diving bell. Sir Francis Bacon provides the description of another bell in the sixteenth century. He wrote, “A hollow vessel made of metal was let down equal to the surface of the water and thus carried with it to the bottom of the sea the whole of the air which it contained. It stood upon three feet — like a tripod — which were in length something less than the height of a man, so that the diver, when he was no longer able to contain his breath, could put his head into the vessel and, having filled his lungs, return to his work.”

Considerably more than 100 years passed without any substantial improvement in diving bells. It would seem that in the meantime the general line of research had veered back to the diving suit. Along this line investigators in several parts of the world were making experiments which seem somewhat fantastic to us but were, nevertheless all steps leading to the ultimate perfection.

First Helmeted Dress

In 1783, a Frenchman named Forfait produced a helmeted dress. The dress was remarkable because it was the first-

The first reliable evidence of a practical diving bell is of the one which Dr. Edmund Halley, the astronomer, designed in 1717. It was a chamber, made of wood, large enough to accommodate five men. In the shape of a huge church bell, it could be operated 50 to 60 feet deep, and was known as Halley’s Diving Bell.

It was ringed about at the bottom with lead. This was to cause it to sink and also to keep it upright on the bottom. Air was fed into the bell from barrels connected with the bell by leather tubes. These air-

THE MODERN DIVING CHAMBER was originally patented in London in 1917 by Sir Robert Davis. Diving chambers on the same principle are widely used abroad. This photograph was taken when the U.S. experimental submarine S4 was submerged to a depth of 60 feet off Rhode Island, U.S.A. Two men in the submarine were brought to the surface in this special diving chamber lowered from the Falcon.

The coverings in the suit included a helmet, a jacket, a belt and breeches. The greater part of the arms was left free and uncovered, also part of the legs. Watertight connexions were made between the four parts of the suit, and air was obtained by means of a twin breathing pipe leading into the helmet opposite the mouth This pipe was sup ported on the surface by a float. There was a touch of unimaginative antiquity in the shape of the helmet. It was a colossal affair which ended somewhere near the waist-

Augustus Siebe in 1829 designed the open helmet diving dress, so called because the canvas jacket was left open at the bottom to allow vitiated air to escape. The chief drawback of this dress was that the diver had to work in water up to his chin. This drawback compelled him to exercise care to remain rigidly upright and limited his effectiveness as a workman. Siebe realized the defects of the open helmet type of dress and experimented continuously in search of an adequate substitute.

After ten years he found it, and in 1839 there came into being the first strong tanned twill dress, fitted with tight-

Condensation on the front glass due to the diver exhaling had been one of the minor problems unsolved by earlier investigators, and it is not difficult to imagine the plight of a diver trying to see through glass fogged by the mist of his own breath. And although it was so near, he could do nothing to remedy the nuisance because the mist was on the inside. Siebe removed the trouble by putting three channels along the top of his helmet and arranging the inlet and outlet valves so that there was a continuous flow of air along the top channels. For the first time it became possible for a diver to inhale and exhale without “blinding” himself.

TELEPHONE APPARATUS FOR DIVERS was originated in the 1890s by Siebe, Gorman and Co., and has been supplied to the Royal Navy ever since. Here, a German naval officer is seen giving instructions to the diver below, while another diver prepares to descend.

There were other details about this suit which show what a remarkably serviceable suit Augustus Siebe brought out almost a century ago. There were the heavy breastplate, the shoulder weights, the lead-

The dress was in itself as nearly perfect as it could be. Minor improvements in rubbering the tanned twill were made, but in general form the dress could not be bettered. All later improvements were in the disposition of the valves and in types of valves. At first it was an inset valve, placed somewhat inconveniently near the back of the helmet on the left side. Then it was brought forward and the controlling wheel was made to jut out from the helmet. Finally this wheel was given a milled or fluted edge, thus enabling the diver to manipulate it easily when his fingers were cramped by cold.

The modern diving outfit, excluding the air pump, consists of six parts, every one of which was found in the original design of Augustus Siebe. The suit consists of a non-

One of these special types owes its existence in part to the firm of Siebe, Gorman and Co., the joint inventors with H. A. Fleuss of the “independent suit”. This is a suit, weighing only 26 lb.— as against the 170-

The “Independent Suit”

In a cylinder strapped to the back is compressed oxygen. Beneath this is a tank filled with caustic soda. This absorbs the carbonic acid gas exhaled by the diver, and thus he is able to maintain a constant supply of nitrogen inside his dress. He can, so equipped, remain under water indefinitely. This dress was patented in 1880, and two years later proved invaluable in the disastrous flood which poured into the Severn Tunnel.

One of Siebe, Gorman and Co.’s divers, wearing an “independent suit”, was able to make his way a quarter of a mile into the tunnel and close the iron door and sluice through which the water was pouring. No diver dependent upon an air supply through pipes could have negotiated the rushing water and swirling debris. There has been no change of any importance in this design and it is still used for dives which cannot be undertaken with the ordinary suit.

Another suit adapted to special occasions, such as abnormally deep dives in efforts to locate sunken submarines, is the all-

The diver in the ordinary suit sinks by his own weight, guides himself down by what is called a shot rope and controls the speed of his descent by manipulation of the air valves. The less air he allows to escape through the outlet valve the more buoyant he becomes, and therefore the slower is his descent. The armoured diver has to be lowered into the water and is suspended by chains.

The most important recent invention in connexion with diving operations — the submersible decompression chamber, invented by Sir Robert Davis — is referred to in the chapter “Diving Adventures”. To-

AFTER A COLLISION in the Thames estuary. The British steamship City of Lancaster, 3,049 tons gross, had been in collision with the oil tanker San Gerardo, 12,915 tons gross. The City of Lancaster suffered considerable damage, her engine-

You can read more on “Diving Adventures”, “Diving for £1,000,000” and “Dramas of Salvage” on this website.