© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

The Battle of Lepanto

In the sixteenth century the continuous assaults of the Moslem corsairs on Mediterranean trade routes aroused the Catholic nations of Southern Europe to action. On October 7, 1571, an Allied fleet routed the Turks off Lepanto (Navpaktos) in the Gulf of Corinth

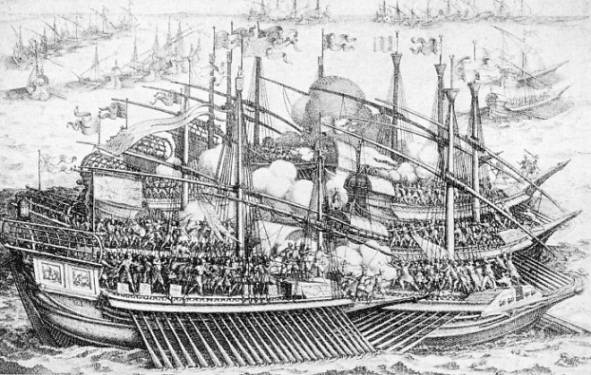

GALLEYS OF SPAIN, VENICE AND THE PAPAL STATES in action against the Turkish fleet. The Moslems had 333 vessels, of which 230 were galleys, the rest being either galleasses or small craft. The Allied fleet numbered 271. Don John of Austria, the Allied Commander-

WHEN we think of warship development, in Europe and elsewhere, since the battle of Salamis, which was fought in 480 B.C., it is strange that Mediterranean sailors should have remained so conservative as to rely on oared galleys as their fighting ships as late as the sixteenth century of our era.

A thousand years had come and gone, battles had been won and lost, but southern fleets-

While Drake and his fellow’ Elizabethans held the Mediterranean galleys in supreme contempt when there was any wind at all, the Mediterranean, from one end to the other, still continued faithful to an old tradition and made few serious attempts at improvements. Only with the adoption of the triangular sail, in place of the squaresail which Greek and Roman galleys had used when going to or from battle, was any real modification introduced. This sail became so characteristic of the Mediterranean that European mariners called it the “lateen”, or the “sail of the Latin peoples”. To-

When the Arabs introduced to the Mediterranean mariners this triangular-

Objection to the gun was partly based on prejudice and ignorance, though by the mid-

In the eighth century A.D. this Oriental rig was more generally used as the spread of Moslem power advanced in Europe. Spain came under Moorish rule. Southern France was overrun by the Moslems, who threatened to dominate western Europe. The whole of North Africa from the Atlantic to the Nile was under the infidel’s sway, till at last in 1492 the conquest of Granada by the Spaniards weakened the domination of the Moslems. Nor did this mixed race of Arabs and other elements remain inactive. They were pioneers in mathematics, able architects, scientists and first-

Of great daring, gifted intellectually, full of bitterness that after seven hundred years they had been expelled, these avaricious and bloodthirsty rovers stopped at nothing. They neither expected mercy nor granted it, so that the mere mention of the Moors was enough to strike terror into women and children. Every trader from England, Genoa, Spain or Venice well knew what might be expected if the wind fell light and a well-

The Corsairs Triumphant

By the sixteenth century the Catholic countries of southern Europe hated the Moslems with a remarkable vehemence, inspired not only by the assaults made against trade routes, but also by the recollection that their enemy was in possession of the Holy Land. The daring and independence of the Moors and Turks roused Christian rulers to frenzy, but a series of expeditions directed against the corsairs had achieved no lasting success. Matters reached a crisis in 1538 and a battle was fought at the south-

In 1570 Philip II (who had married Mary Tudor of England) was King of Spain, Pius V was Pope and Selim II was Sultan of Turkey. Deputies from Spain, Venice and Rome met with a view to co-

It was an ambitious plan, backed by strong influence, fed with general enthusiasm, and supported by unlimited funds and resources. Every man took a personal interest; many of them belonged to families which had already suffered at the enemy’s hands. Don John of Austria was to be Commanderin-

Another man of birth and position, but one year younger, was Cervantes, whom we remember as the novelist who wrote Don Quixote. Cervantes was to serve as a private soldier in the forthcoming battle on board the galley Marquesa, and to receive permanent injury to his left hand.

Fired with the news of the League’s preparations, the Sultan likewise began to collect from among his fellow Mediterranean Moslems and from his imperial resources a large and powerful fleet, over which he placed his brother-

In Portugal and Spain the maritime arts had long prospered, and shipbuilding, if crude, was one of the oldest skilled trades. For this undertaking ninety royal galleys and over seventy other ships were ordered to be built. During the first week of June Don John travelled from Madrid

to Barcelona, whence he proceeded with thirty galleys to Genoa, which was reached the same month. Having sailed on to Naples, Don John there found awaiting him, ready for sea, the squadron of the Marquess of Santa Cruz. That was in August, and after a halt of ten days he moved on to Messina, in Sicily, where the combined squadrons saluted Don John as their Admiralissimo.

Galleys Armed with Guns

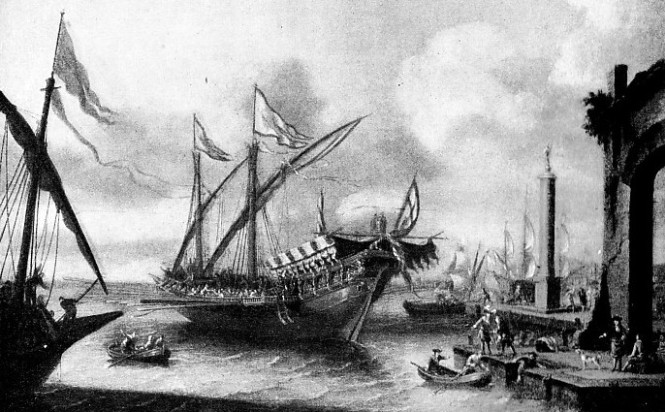

Such an assembly of shipping had never been known since the days of Imperial Rome, and certainly not since the dawn of Christianity. Every day brought additional galleys and brigantines, which were quite different from the two-

Resplendent in Messina’s spacious harbour, over 300 galleys, brigantines and smaller units assembled in brave array under the brilliant sunshine. The galleys were richly carved and expensively gilded. From masthead, ensign staff and peak there flew many coloured streamers and flags. Don John’s flagship, the galley Real, had a stern ornate with historical emblems, and her deck-

The Spanish contingent numbered ninety royal galleys, twenty-

Those who rowed the galleys were known in different parts of Europe as forcats, forsados or forsathes and received no wages, generally being convicted criminals or prisoners of war who sat chained to the thwarts. Cristofolo da Canale, a Venetian officer of that time, wrote: “Galleys manned by condemned men surpass those rowed by freemen, but magistrates should send only healthy men to the galleys”. For, whereas the freemen were few, these volunteers needed bounties as well as increased pay to tempt them afloat; moreover, they could not be denied shore leave.

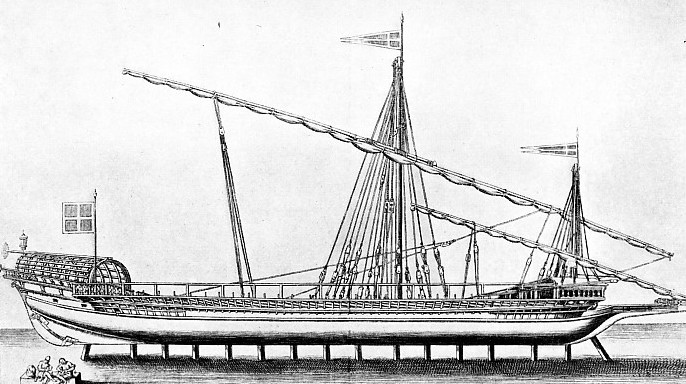

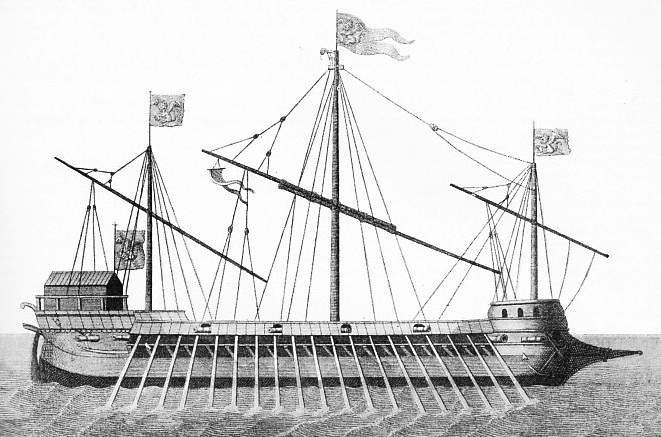

SIXTEENTH-

In a sixteenth-

The great length of the yards (to which the lateen sails were stowed), the relic of the ancient ram projecting from the bows, the framework aft (over which an awning was spread for the protection of the commanding officer), and the extreme shallowness of the hull were noticeable features.

Down the galley’s centre, along a corsia, or gangway, walked two men who lashed or smote the unfortunate rowers to make them do their best. Such a vessel measured 169 feet from beak to stern, the extreme beam being about 20 feet. Before the vessel went into action sails were stowed and the oars were used exclusively. It was not unusual for 324 men — six men to each oar — to be pulling at twenty-

In bad weather these galleys received a slight protection from having a foredeck, but they were exceedingly wet as they butted into a head sea. Fortunately we know from the Bishop of Mondonedo, who had been to sea with Don John’s father, how unpleasant life in one of these vessels could be.

Life in the Galleys

Mondonedo wrote, “The passenger in a galley must be humble . . . for in going on board he sacrifices his liberty . . . You find neither a bench to lie on, window to look out from, table to eat on, nor seat to sit on”, though sometimes you might be allowed to repose on the gangway. You ate on the deck, as the sailors did, “or on your knees, like women. Be careful not to throw water on the deck of the poop ; still more not to spit there, for fear of being rudely called to account by the captain and fined. Sailors spit in our churches, but redden with anger when we do as much in their ships. When going to sleep, you do not remove shoes or socks or coat; passengers and sailors lying down pele-

Privacy was impossible, good, clear drinking-

The only food which the oarsmen were supposed to require consisted of water, wine and vermicelli. Even if they were not rowing and the Venetian galley proceeded under sail, the heavy yards made her bury her rail so that the men at the lee side were washed down by the seas. These craft normally had only twenty inches of freeboard when on an even keel, though the Turkish galleys carried their deck half a foot higher. The Turks used sails made of a light cotton instead of hemp, which were half the weight of the Venetian sails; thus the Moslems could always sail the faster.

With this detailed description we shall be able readily to picture the battle and appreciate the limitations of sixteenth-

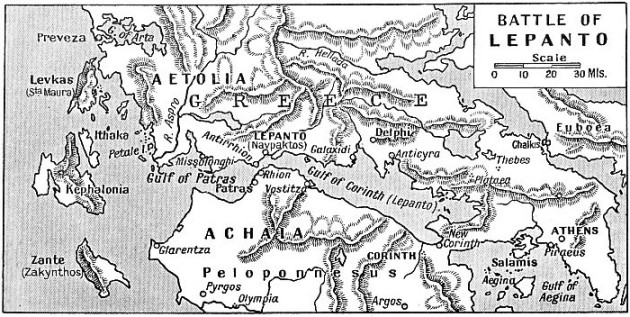

IN AN ARM OF THE IONIAN SEA, the position of Lepanto is clearly indicated on the above map. Four of the Ionian Islands — Levkas or Santa Maura, Kephalonia, Ithaka and Zante or Zakynthos — guard the entrance to the Gulf of Patras. Corfu, the best-

The Gulf of Lepanto, better known as the Gulf of Corinth, almost separates the Morea, as the Peloponnesus was called in the Middle Ages, from the northern part of Greece. It is approached from the Ionian Sea through the Gulf of Patras. Off the west coast of Greece are the four Ionian islands of Levkas (or Santa Maura), Ithaka, Kephalonia and Zante (or Zakynthos). Lepanto, now called Navpaktos, lies on the northern shore of the Gulf of Lepanto, near its western end, in the Bay of Lepanto.

Having consulted with his officers, many of whom were old enough to be his father, while the grey-

Under the shadow of mountainous peaks covered with olive plantations and woods, away from interference of the outer world, Corfu was an ideal spot for Don John. Here, while waiting for his laggard transports, he formulated his plans. Here, too, he reviewed and drilled his fleet. On October 3, unable to waste further time, he sailed down the coast without the missing transports, past the scene of that other historic battle of Actium, working his way past islands that one day were to be the hunting grounds of German U-

“No Paradise for Poltroons”

Having reached the east side of Kephalonia, Don John was held up for two days by head winds; but on October 7, with unsettled weather and the wind falling lighter, the massed squadrons set sail two hours before dawn. Between Kephalonia and the mouth of the Gulf of Patras there is open sea for about twenty miles. At that time of the year the prevailing winds are usually light and variable from west or north-

Don John’s officers knew the coast and weather well enough to give him sound advice, which as a soldier he wisely accepted. Everything turned out well. The fleet got across in two hours at 10 knots — no difficult accomplishment for these easily driven, light displacement craft. But the breeze was not normal to-

When once inside the two horns of the Gulf of Patras, the Allied fleet would be in comparatively sheltered waters, although Lepanto Bay, another thirty miles farther on, was not a particularly safe anchorage during south-

The risen sun now revealed the Moslem fleet. It numbered 333 vessels, of which 230 were galleys, the rest being either galleasses or small craft. These figures are given by de Romegas, who was present, and show a preponderance over Don John’s 271. The Christian fleet was no ordinary expedition but rather in the nature of a Crusade, with a deeply religious purpose. Victory or defeat would mean so much to Europe. The civilized world was hoping that Don John would do all that it expected him to perform. Rarely has a young man borne such responsibility on his shoulders.

The sighting of the enemy came at a dramatic moment. The climax could not be long delayed. During the final approach, by orders of the Commander-

With dramatic and significant gesture the League’s standard, which had been solemnly blessed at Naples, was now unfurled on board Don John’s flagship Real just forward of the poop. Each galley captain had already received written instructions as to how the battle-

MEDITERRANEAN CONSERVATISM was demonstrated in the galley, the war vessel which had undergone few modifications in two thousand years. By the sixteenth century Western Europe had developed the ocean-

Don John’s fleet was arranged in three columns, himself in the centre with sixty-

We can picture the 271 vessels being rowed towards Lepanto Bay led by the Real, with Don John’s pennon flying at the mizen peak and the Holy League’s standard fluttering over the poop. The sun at first favoured the Ottomans and shone in the Christians’ eyes, but as the day advanced this position was reversed.

The Impending Clash

The easterly wind had now faded into calm, which made matters easier for Don John’s oarsmen. The approach became still more rapid when the breeze had gone round to the west. This, in turn, made it harder work for the Turks pulling to windward. Don John’s thousands of convict rowers, who had been toiling at their oars from long before dawn, must have already experienced fatigue before the more strenuous work was demanded of them.

When the enemy came forth in line-

In the Ottoman line, at the centre, advanced Ali Pasha, Commander-

The brilliant sun lit up jewelled turbans, and scimitars flashed everywhere. Here was a majestic display of ships and of men inured by countless raids and sea-

It may well be asked whether the snipe-

When the two fleets were approaching each other the commanding officers of the wings on either side naturally tried to take every advantage of the north and south shores so as to get all possible flank protection. The idea was overdone, and the wings became too much separated from the centres.

A Bad Start

Ahead of the main Christian fleet were its six galleasses, but the first gun was fired by Ali Pasha —evidently to try the range. Don John replied, each rival fired again and silence intervened.

When at last they were within range, the foremost Ottoman ships opened consistent fire as the wild Turkish cries rent the warm air, and the sound of the Real’s trumpet call to action was carried down wind into the ears of the Christian slaves.

From their position half a mile ahead, Don John’s galleasses, with their heavy armament — the Mediterranean precursors of the battleship — were able to make such execution that the Turks’ advancing galley line had to open out and pass this special squadron on either side without engaging. While the Christian left wing under Barberigo was hugging the coast, the Venetian admiral, not having as much local knowledge as Sirocco, feared to get ashore on the banks. Thus a small space was left between the Venetian squadron and the north shore. Quick to perceive so much, Sirocco drove his galleys at great speed, wedged his squadron between shore and landmost enemy ship, and thus made a flank attack which sank eight Christian galleys and captured others. Barberigo received an arrow in his eye which wounded him mortally.

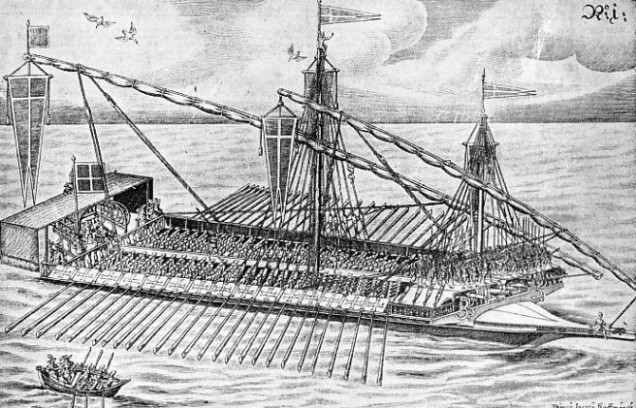

VENICE’S CONTRIBUTION to the Allied fleet comprised six great galleasses — one of which is illustrated above — 106 galleys, two nefs (transports) and twenty light craft. The galleass was larger than the galleyas she had three masts instead of two, and was more heavily armed. She was propelled both by sails and by oars. The vessel illustrated has nineteen oars on the starboard side, which shows also eight guns distributed along her length. Thus she did not suffer from the disadvantage of the galley, which could fire forward only.

This reverse was a seriously bad and disappointing beginning, but nothing so adequately indicates the valour and determination to win as the quick rally which followed. Having beaten off their adversaries, the Christians, sword in hand, boarded and captured ship after ship. In some enemy ships the galley slaves themselves broke their fetters, leapt from their benches and joined in

the fray against the Ottoman masters who had so long maltreated them. The climax at this end of the line coincided with the sinking of Sirocco's galley. Then his squadron fled before the Venetians, some of his ships escaping by running up the neighbouring shore. So much for Don John’s left wing.

His right wing was commanded by John Andrea Doria, opposed to whom was Uluch Ali, the practised corsair. Uluch tried exactly the same tactics as Sirocco, but, with all his skill, he was facing as able a tactician as himself. Doria, realizing the intention, extended his own line so close to the land as to thwart the Dey, but in so doing left a wide breach which exposed Don John’s centre. Uluch saw the gaping opportunity, rushed in as a wedge and separated some of the Christian galleys, sinking some and towing one away.

The wings of the Christian fleet withstood the onslaught. With the attack on the centre, as might be expected, there came the last and greatest trial, as between two giants. The Real flew the Holy League’s sacred standard, and Ali Pasha displayed the wide Ottoman banner, ancient and revered, decorated with golden letters from the Koran.

Ali Pasha’s bigger and loftier vessel fell upon the Real in such a manner that the Moslem’s prow reached the Spaniard’s fourth rowing bench and then rebounded.

On board the Real were 300 Spanish arquebusiers, with their portable guns resting on forked supports. Ali Pasha had a like number of Turkish infantry and 200 archers. Arrows, muskets and cannon were all directed against the Real, but the Ottoman gunnery was not good and aimed so high that the cannon balls went over Spanish heads. Moreover the Real’s hull sides were protected and the Moslem’s were not, so that at close range Don John’s ordnance deluged the enemy’s decks with terrible destruction.

Peak of the Battle

To Don John’s aid came Colonna and the seventy-

This was the peak of the whole battle, when fighting took the place of propulsion and every man would be necessary to turn the scale. Don John therefore unchained his convict oarsmen and threw them into the fray. Then came the third assault on the Ottoman flagship. A musket ball had knocked Ali down to the deck but had not killed him.

At this moment one of Don John’s unchained oarsmen, armed with a sword, saw the opportunity of a lifetime and the chance of liberty. Brandishing his weapon, he advanced towards Ali and slew him.

With the Turkish commander’s death, the capture of his galley, the lowering of the Crescent and the hoisting of the Christian flag, the turning point in the battle had been passed. The enemy’s centre collapsed, just as the wings had folded up. One hundred and thirty Moslem galleys were captured. All the rest of them were either burnt or sunk, except a few which got on the rocks and fifty which escaped under the leadership of Uluch.

The losses at Lepanto were certainly great. One authority gives those of the Christians as 15,000 and those of the Moslems as 50,000, though this may be an exaggeration. From 12,000 to 15,000 Christian slaves are said to have been released from the benches.

DOWN THE GALLEY’S CENTRE, along a gangway known as the corsia, walked two men who urged on the unfortunate oarsmen with frequent lashes of their heavy whips. Those who rowed in the galleys were generally convicts, who sat chained to the thwarts, or prisoners of war. Occasionally freemen were employed. A contemporary writer remarked: “Galleys manned by condemned men surpass those rowed by freemen, but magistrates should send only healthy men to the galleys”. The galley illustrated has twenty-

You can read more on “At Sea in the Middle Ages”, “The Battle of Salamis” and

“From Tudor to Victorian Times” on this website.