© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

The Battle of Salamis

Under the leadership of King Xerxes, an immense Persian army, supported by a fleet of unexampled size, invaded Greece in 480 B.C. Undaunted by this menace, the allied Greeks met the Persian fleet in the strait between the island of Salamis and the Greek mainland, and totally defeated the invader.

DECISIVE NAVAL ACTIONS - 1

SALAMIS TO-

IT IS because human nature through the ages differs so slightly that the story of Salamis will always remain so fascinating. Moreover, while ships of one century may have an appearance, a size and even a means of propulsion different from anything hitherto adopted, yet the main principles of naval warfare continue unaltered.

The campaign that culminated in the historic sea-

Almost five centuries before the Christian era, Darius I, who had founded the Persian Empire, was succeeded by his son Xerxes in 485 B.C. Xerxes resolved to invade Greece on an immense scale with the twofold idea of controlling the European coast of the Aegean (since he was secure on its Asiatic coast), and of adding the entire Balkan peninsula to his already expansive territory. He was an ambitious man longing for new triumphs, and the question was whether the ancient hostility between East and West would end by Persia imposing its civilization over European progress.

The grandeur of Xerxes’ idea, the gigantic preparations that he made between the year 485 and the spring of 480 B.C., overwhelm the imagination. For gathering men and material he had the whole area from the Danube to the borders of India on which to draw. He proposed to invade Hellas (Greece) with a great army and a great fleet. The army was to march all the way from Asia, crossing the water at its narrowest point in the Dardanelles, thence skirting the northern end of the Aegean, and advancing south through Macedonia and Thessaly on to Athens. The fleet, so far as geographically practicable, was to hug the coast and keep in close touch with the army.

From the maritime resources of Egypt, Phoenicia, Cyprus, the coasts of Asia Minor, the Sea of Marmara and the Black Sea, Xerxes managed to accumulate 1,200 triremes crewed by 276,000 men, of whom 36,000 were marines. Later he added another 120 European triremes and 24,900 men, as well as the transports and victuallers necessary for feeding his army. A fleet of 1,320 fighting ships carrying 300,000 men would seem immense in any age, but how much more wonderful were these figures at a period when the known world was less populated.

In the autumn and winter of 481 B.C. the concentration of ships and men from so many harbours in Asia Minor was being made up the Dardanelles at Abydos, a little north of Chanak. Here centuries later British battleships and aeroplanes were to hurl shells and bombs against Turko-

Xerxes' army marched towards Abydos. Here the width was under two miles and the current was strong. The Persian soldiers were sent across to the European side at Sestos on a bridge built from boats whose bows pointed upstream.

Now began that twin advance of the army by land and the fleet by sea. The reader will immediately perceive the essential weakness of Xerxes’ plan. For the men’s food and the forage for horses the Persian army depended on the big-

Sail at a Disadvantage

One great advantage in ancient days was that a fleet could be brought into being quickly. To-

It was largely used also for the round, big-

For manoeuvring ability, shallow draught and light construction were requisite, and these galleys contained room for little else than their crews. At night such craft were generally hauled ashore, and the men bivouacked and cooked their food on the beach. It must have been a marvellous spectacle when Xerxes’ fleet was favoured with a fair wind, and the vessels set their square sails, which were made of canvas or cloth and frequently coloured. To have seen this multi-

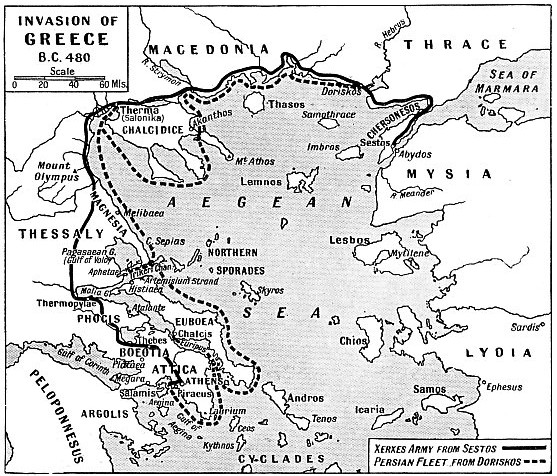

ROUTE OF THE INVADER. In the autumn and winter of 481 B.C. ships and men were concentrated at Abydos, on the Asiatic shore of the Hellespont (now the Dardanelles) at its narrowest point. The Persian host crossed over to Europe on a bridge of boats, and marched through Thrace, Macedonia, Thessaly, Phocis and Boeotia into Attica. As far as geographically practicable, the fleet, of 1,320 sail, followed the army. To avoid the stormy promontory of Mount Athos, Xerxes cut a canal for his ships across the peninsula. An attempt to annihilate the Greek fleet in the Trikeri Channel, to the north of the island of Euboea, was frustrated by a gale, which destroyed 600 of the Persian ships. After an indecisive action off Artemisium, the Persian fleet was lured into the strait between Salamis and the mainland.

The scouts ahead had sails and gear dyed the colour of the sea for purposes of camouflage. Two kinds of sails and two kinds of masts were carried. Just before battle the larger kinds were put ashore as encumbrances, but the smaller ones were stowed away lest they should be needed for escape at the last minute. The generic term for smaller mast, sail and gear was akation, so that the expression “hoisting the akation” came to mean “running away from the enemy”. The yard was hoisted up, the mast reefed and brailed, by means of ropes made either of twisted oxhide or of the fibres of the papyrus plant.

Steered by an oar-

Thus, instead of being gun platforms, these ancient warships were mobile surfaces for fighting hand-

The chief weaknesses of this ancient warfare may be summed up under two heads: the extreme vulnerability of hulls, and the reliance on human physical endurance. Although — except among the free Greeks — slaves were used as rowers, driven to the last limit of their strength, and almost beyond, the range of a fleet’s action was restricted to that of a few hours. On the other hand, these ships, with their standardized design, could be built quickly and in large numbers from the local timber.

Xerxes’ army marched on through Thrace, from Doriskos to Akanthos, and the fleet kept abreast between the island of Thasos and the mainland. No little anxiety was felt as the ships approached the mountainous peninsula of Athos, where it projects from south Macedonia and rises 6,000 feet out of the Aegean. Ancient mariners always dreaded rounding this promontory, and here in 492 B.C. a Persian fleet had been wrecked completely; but Xerxes, with the grand gesture of a mighty ruler, defied such geographical difficulties. The king who by triremes, stout ropes and windlasses had bridged the Dardanelles, had also foreseen the Athos risk and the possibility of losing his fleet. Therefore he had caused a canal to be dug right across into the gulf at the other side of Athos, and the ships passed through in safety. Traces of this canal, after more than 2,400 years, are visible to this day.

Xerxes had now accomplished a large portion of the first stage of his expedition. His army marched across to Therma, better known to us by the name Salonika. By fine staff work, excellent preparation, making roads, building bridges, levelling ground and erecting depots, the army of Xerxes had reached thus far, and prepared to march southward.

The army started from Therma eleven days ahead of the fleet and crossed the passes into Thessaly. Then the fleet, preceded by scouts, moved out under four admirals, probably organized in three divisions. They made their first contact with the enemy by capturing a few light vessels placed on the look-

In about July 480, the Greek fleet had occupied Trikeri Channel, which separates the island of Euboea on the north from the mainland. At the western end of this channel, in the Gulf of Malia, lies the pass of Thermopylae, and if only the Persian army could force the pass, Attica would be overrun. Athens was fewer than a hundred miles away. Obviously an important clash would take place in or about Thermopylae, by sea no less than on land.

Disastrous Prelude

Although for some time the Greeks had been slow to appreciate the impending threat, necessity had at length enlivened them to energy, thanks largely to that fine Athenian statesman Themistocles, who caused a fleet to be built. Instead of distributing the surplus profits from the silver mines at Laurium, in Attica, the money was spent on building ships. Each trireme cost about one talent, or the equivalent of £225 by the standard of values as reckoned in 1914. Never was money more suitably spent.

These galleys rowed or sailed round from the south between the mainland and Euboea, under the leadership of Eurybiades and Themistocles. This ninety-

It was a sound bit of strategy, but one of those three-

THE CRESCENT-

THE CRESCENT-

The loss of 600 fighting units, with the disorganization of his plans, was a serious blow to the Persian King. In addition, the rest of his fleet had been prevented from feeding his army. As the gale moderated, his naval force shifted from Cape Sepias to Aphetae, at the entrance to the Pagasaean Gulf, known to-

Artemisium lay about thirty miles from Thermopylae. The straits across from Artemisium to Aphetae were some seventeen miles wide. Not until the late afternoon did twenty-

Up to now the Persian fleet had been out of touch with Xerxes for seventeen days. It had done nothing to assist his army, and the king sent urgent orders that the straits must be forced. Therefore on the third day after the gale the Persian fleet came out from Aphetae about noon, forming their line crescent-

There arrived, however, this evening at Artemisium in his fifty-

After a council of war it was decided that the Greek fleet should retire at once and go south. The cloak of night had to be used to cover retreat, and while the specks of Greek sailors’ camp fires were left to flicker and make the Persians unsuspecting when their light craft investigated from a distance, Greek galleys cautiously stole round the west of Euboea through sheltered waters.

It was all done with the utmost speed but in perfect order. Themistocles, with a fast division, formed the rearguard. When a man in a boat from Histiaea came along to tell the Persians that the Greeks had departed he was not believed till the sun rose. Having shifted their base across to Artemisium, the Persians also left (at noon) for Histiaea. Now they could regain close touch with Xerxes and send him supplies; yet, being so tethered to the army, they were unable to pursue the Greeks and deal a smashing blow. This was another mistake for which the Persian king had to pay heavily.

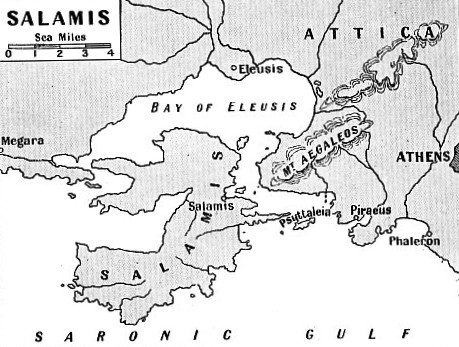

Meanwhile the Greek fleet, still intact, still full of fighting spirit, went south. It covered the distance from Artemisium to Salamis (160 sea miles) in a night, two whole days and another night. A halt had been made opposite Chalcis by the Plataean contingent to remove refugees, who were taken to the island of Aegina in the Saronic Gulf. Here also Athenian families were transferred, as well as to the island of Salamis. Salamis lies about half a dozen miles from Athens, and has an area of thirty-

It was Themistocles with his high moral courage who, amid clamorous panic and despair, persuaded the Greeks to hold fast at Salamis and fight a final battle in this strait, where the geographical confinement entirely favoured a small number of ships and hindered a bigger fleet from free manoeuvre. To contend in the open sea would be all to the advantage of numbers, whereas the encircling land would in itself be a protection to the weaker fleet. It seems curious, therefore, that Xerxes should so easily have suffered himself to be trapped. After his victory at Thermopylae he had marched south by way of Thebes and reached Athens, which he found virtually evacuated. His fleet came south, too, and could have blockaded the Greeks in the strait and ruined their morale. It could have kept Eurybiades and Themistocles inactive while the Persian troops made their deadly raids throughout the Peloponnesus. In short, a universal victory was fully ripe. Xerxes, however, sought advice from his admirals, and they offered unfortunate counsel.

A Well-

The Persian fleet had remained at the northern end of Euboea until three days after the army had departed from Thermopylae. In another three days the ships arrived at Phaleron Bay, which was then the port of Athens. When Xerxes went down to his ships, all the subordinate rulers and admirals were questioned individually as to whether he should attack the Greek fleet. The only person who opposed the idea was Artemisia, Queen of Halicarnassus, who, as a vassal of Xerxes, had come with her squadron in the great adventure.

Thus we come to the climax and quick ending of this drama. On September 19, 480 B.C., the day dawned in an extraordinary manner, foretelling a startling result. At sunrise an earthquake shook land and sea, and undermined the people’s faith. The Persian fleet in Phaleron Bay numbered about 700 ships, with 120,000 rowers and hoplites preparing for battle. A few miles away the Greeks were ashore ready to put their 80,000 men aboard the 370 ships at short notice. The Persians had nearly twice the numbers of the Greeks.

That afternoon, to lure Xerxes into this well-

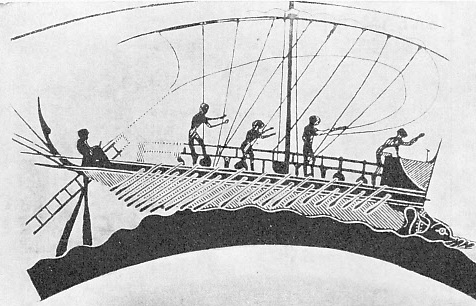

GREEK GALLEY of about 500 B.C., with two banks of oars. Later examples had three, four, five or more banks. This type of warship relied on the ram for attacking enemy vessels. A fighting galley was, in effect, a spear. The ram was its point, the hull its staff, and the oarsmen the arm that hurled the spear. The sail was useful only for making long passages, or to give the oarsmen a rest. Down to the fifth century B.C. the crews of Greek war vessels were freemen and not galley slaves, as was the practice among Oriental nations. Despite their small radius of action — due to the fact that they carried no reliefs — the galleys were remarkably fast. One of them is recorded as having covered 168 miles in twenty-

Thereupon Xerxes ordered his vessels to leave after nightfall. They were to be formed in three lines, guarding the eastern exit from the strait. Likewise they were to cut off the Greek retreat at the western end, where the channel contracts abreast of Megara. As it might be possible that Greeks, no less than battered Persians, would in the course of battle be driven ashore on Psyttaleia, Xerxes ordered that island to be occupied with Persian troops. At night, therefore, the first movement began. By dawn on September 20 Xerxes’ three lines of galleys were stationed just to the southward of Psyttaleia, thereby blocking the two eastern channels. The western end of Salamis was covered off Megara by a detached force of 200 Egyptian craft. From the first, then, the Greeks had by their choice of position forced their enemy to divide ; and now, with only 500 opposing 370, the situation was not too unfavourable, although scarcely promising, since the Euboean plan might this time succeed in squeezing the Greeks into destruction For the Persians this separation of strength was inevitable, since the chosen locality was thoroughly unsuitable for a large fleet.

The Persians did manage, however, to spring a surprise. These extensive night preparations were carried out in strict silence and without any man taking sleep. The Greeks seem to have been singularly unwatchful, for, despite the few intervening miles, they had no idea that their enemy had taken up a new position, nor even that the fleet had left Phaleron. Part of the night was spent in discussion by the Greek officers.

Tidings burst in on them that the Persians were approaching, but that report was dismissed as untrue. Not until the arrival of a trireme which had deserted from the enemy did this news gain acceptance. The time for discussion suddenly ended and the great day was at hand. As the sun rose the admirals summoned the sailors, whom Themistocles addressed in an eloquent speech. He then sent them aboard the anchored ships of the allied Greeks.

Dense and extensive as a jungle were those lines of wooden galleys, needing every yard of the available space, for they were each 150 feet long and 18 feet in beam, and the length of their oars measured 20 to 30 feet. Confusion of one galley’s oars getting foul of another craft would be all too easy, even with careful steering. Thus there could not have been more than fifteen lines abreast, every line consisting of about twenty-

Momentous Onslaught

As the strait north of the Dog’s Tail was under 2,000 yards wide, the twenty-

Against the browns and brilliant reds of the Salamis hills, and the green pinewoods of Mount Aegaleos on the Attic shore, thousands of oars gilded by the rising sun splashed into the blue water furiously as the Greeks and Persians moved towards one another. The sight of 870 craft in view simultaneously, with another 200 only seventeen miles to the westward, was one of the most magnificent spectacles ever seen.

Naval history can provide no parallel to the battle of Salamis for numbers and momentous import. The sun would not set before two rivals had settled the command of the Mediterranean, the future of Europe, the destiny of the western world.

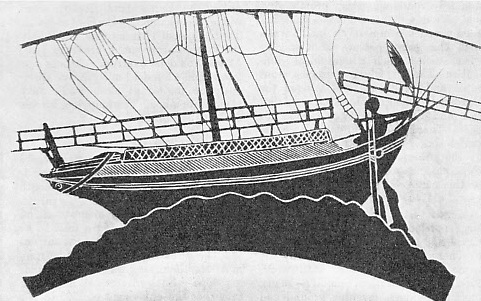

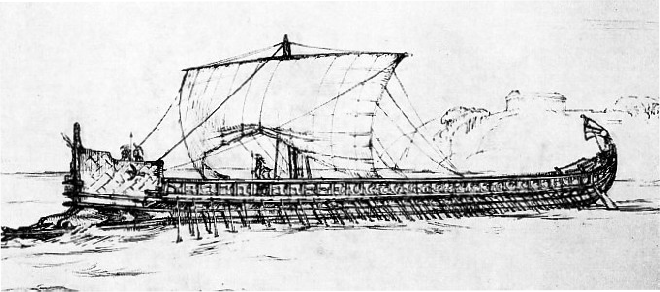

MERCHANT SHIP of about the same period as the galley illustrated above. For transporting foodstuffs and other commodities in bulk the war galley, with its banks of oars and its rowers, was totally unsuitable. To give the necessary cargo space, therefore, a vessel was evolved which relied exclusively on sail. In the example shown, there is one mast stepped vertically amidships; the squaresail is brailed up by means of vertical buntlines. Two steering oars are provided. Additional freeboard is given by the fitting of matting screens. The exact purpose of the ladder-

The approach to the site of this battle immediately indicated the essential difficulties. The passage on the eastern side of Psyttaleia was not more than 1,000 yards wide, and it was impossible for the Persians to compress their enormous fleet through it. They were therefore forced to reduce their front and turn to port through about four points of the compass. This led to great confusion, ships falling foul of one another as they reached the narrows. Against this tangled front the Greeks in good order, though their right wing was the more advanced, came charging with their beaks and caught the enemy struggling in a bottle-

From this stage the engagement, devoid of all tactical skill, developed into a fierce and prolonged hammering. Ships kept ramming one another and Greek and Persian soldiers slashed hand to hand. The Greek soldiers were superior to the Persians because they had weightier weapons. The fight resolved itself into one long wearing down of Xerxes’ men. It is rare for a naval engagement of such importance to be witnessed by so many spectators. The crowds that assembled suggested that some Greek games were being held rather than the tremendous contention for the supremacy of nations. On the island of Salamis the terrified refugees, driven from their homes, fearful of their own future, watched nervously the swaying phases. If the Greeks lost — all was lost, and freedom disappeared for ever.

Across the water, on the opposite shore, a golden throne had been erected on the slopes of Mount Aegaleos. Here sat Xerxes, his eyes intently following his massed ships. For the future chronicle of this notable battle, many of his scribes stood near, writing down the incidents.

They saw at the outset the wisdom of Themistocles. He would not allow his triremes into line-

The same fresh breeze caught the high-

The Final Triumph

One ship, for instance, came rushing past her opponent’s side, crumpling up her oars and leaving her unmanageable; then she turned and rammed her enemy’s unprotected hull. While the Persian fleet remained in a state of confusion a Greek galley chased Queen Artemisia’s vessel, but in front of her were other Persian ships that hindered her escape. Artemisia’s ship tried another outlet so unskilfully as to commit the unpardonable offence of ramming and sinking one of her own fleet. Xerxes from the hill observed the episode with satisfaction, for he was under the delusion that she had rammed a Greek galley.

The telescoping of the Persians’ front ranks, the pressure from their own rear and from the Greek van, made the initial confusion worse than ever. Some of the ships in the Persian rear, being unable to get through to aid those in the front line, retreated to the south of Psyttaleia; but while the centre stoutly fought and resisted every onslaught, late afternoon brought to the Greeks a well-

Xerxes’ brother, Ariamnes, Commander-

The most surprising feature, however, is that the Greek fleet did not turn victory into annihilation. They never pursued the enemy beyond Psyttaleia. There still remained the Persian detachment on Psyttaleia, but soldiers from Salamis were carried across in boats and slew this isolated force.

When command of the sea was lost, the very size of Xerxes’ army became no longer an asset but a serious peril. Greece was too barren a country to provide food for all his men, and his victualling ships were at the Greek fleet’s mercy. Within a few days the disappointed army began its homeward march, and the dejected surviving portion of the fleet scurried across the Aegean independently. The Persians had little desire for further fighting.

THREE BANKS OF OARS are seen in this representation of a Greek galley of the fourth century B.C. A galley with three banks of oars is called a trieres or, more usually, a trireme (from the Latin tri-

You can read more on “At Sea in the Middle Ages”, “The Battle of Lepanto” and “Ships in Miniature” on this website.