Building ships’ models is a fine art reaching back to long-past ages - an international art that will never lose its appeal while men love ships and the sea

DURING the last fifteen years the interest in ships’ models of all sorts, and especially those which represent sailing vessels, has developed significantly. The reason is not hard to appreciate.

There has always been a sentimental regard for sailing ships, and for thousands of years human hands have delighted to reproduce them in miniature. But the shortage of food during the war of 1914-18 suddenly reminded us that we were a seafaring and island nation, to whom shipping was the very means of existence. From that period an entirely fresh enthusiasm for maritime matters was born, and it has continued through the post-war generation. Nor is that the whole story.

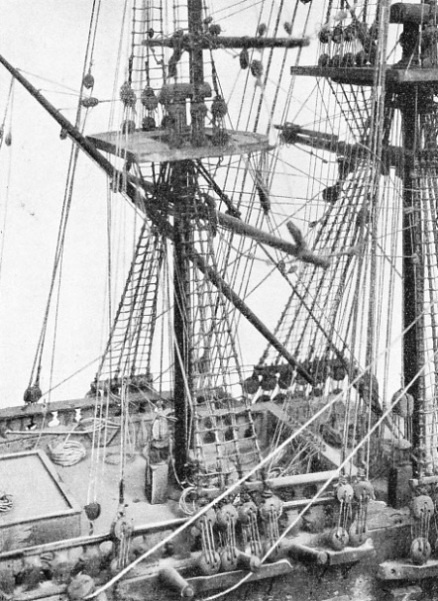

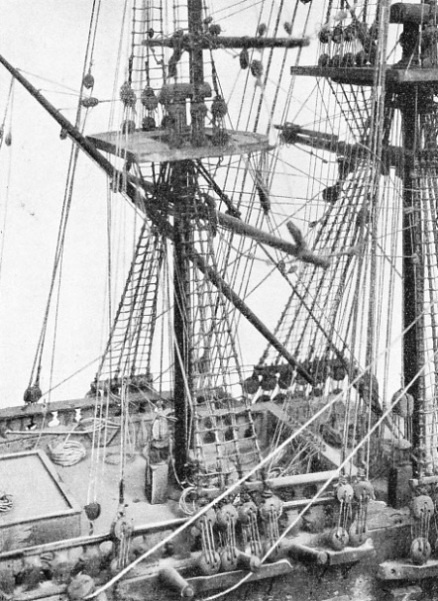

VOTIVE OFFERINGS in the form of model ships were placed in the churches of Catholic maritime countries in early times. In some ports votive models are still to be found. This photograph shows the rigging of a Danish votive ship formerly in a church near Gothenburg, and now in the Maritime Museum of that city.

The 1914-18 period witnessed the last days of the grand old sailing ships that already were finding it hard to live against the opposition of steam. Torpedoes, shells and mines wiped out (with few exceptions) a tradition of centuries. It seemed sad that this should be, and many a ship-lover determined to employ his spare time reproducing as accurately as possible some of those famous vessels belonging to the bygone era. Thus, in recent years there have sprung up in Great Britain and in America enthusiastic ship model societies, whose members are doing splendid work while pursuing a pleasant hobby.

To fashion the hull of a model ship with accuracy; to set up rigging and sails and lead halyards or sheets in a proper seamanlike manner; to produce a finished article that will not offend the sailor’s eyes - this is no simple matter. The task demands not merely immense patience and manual ability, but also technical knowledge and some acquaintance with nautical archaeology. Many of the late nineteenth-century models representing non-contemporary ships are most inaccurate, because they are based on incomplete knowledge. Even twenty-five years ago the number of marine antiquaries was few, museum catalogues contained many an error, and genuine old hulls had been incorrectly re-rigged. To-day, however, the influence of nautical research societies, and the spread of knowledge by means of modern books written in accordance with discovered facts and not with fancy, have enabled model-makers to re-create on small scale a caravel, a galleon, a Caroline merchantman, an East Indiaman, or a clipper ship, without a block or stay being out of place; without, indeed, a single blemish from truck to keel. Some of the modern craftsmen are now producing work which for delicacy and correct detail could not have been excelled by the ablest model makers of the seventeenth century.

Human knowledge, exploration, colonization, commerce, prosperity and invention are all based on travel - on movement from place to place. Life is not static, but progressive, and through the ages it is the sailing ship which has ever been the bearer of new ideas, the means for exchanging wealth. If we rule out of the world’s story the evolution of marine transport, there is little to relate; if we follow the development from skin-boat to ocean carrier, we have the framework of man’s progress.

It is impossible to understand fully the Crusades, the voyages of Columbus, the planting of America, or the Anglo-Dutch or Anglo-French naval wars, unless we know how the ships looked, how they were rigged, what accommodation they afforded, and how they carried their armament. Many of the inaccurate eighteenth and nineteenth century prints completely fog the mind. Even to-day some artists (though fewer than hitherto) make the most absurd sea pictures with ships that are meaningless. But one glance at an accurate ship model shows that sails and ropes have their special purposes, that there is a scheme in those masts and yards, and that a line-bowed clipper ship could do things that Drake’s Golden Hind was prevented from achieving. The model of a ship permits of no faking, no cleverly disguised insincerity, no vagueness or artistic licence. Either it is perfect down to the smallest detail, or it is a wasted effort. Few results are more ludicrous than a badly-expressed portrait of a ship.

The number of early drawings and paintings dealing with seafaring is comparatively few, for the reason that until after the sixteenth century travel by ship was regarded with nervousness and even with horror. Artists did not care to set down subjects that aroused unpleasant memories, except for some special purpose, as, for instance, commemorating the deliverance from shipwreck after a storm. Occasionally a medieval artist’s subject shows a contemporary vessel in the foreground, though more frequently it is placed inconspicuously in the background. Not, perhaps, till the Van de Veldes of the seventeenth century, and the confidence begotten of reliable ocean-going and well-found vessels, does marine painting properly begin. No longer are pictures of ships mere caricatures, but genuine portraits, accurate as to rigging, set of sails, running gear and details of ornamentation.

A drawing or painting does not however, completely satisfy; at the best it is flat and only partly realistic. We cannot see the hull below water, nor touch the planking, nor set the yards according to the wind. We must needs accept what the artist has seen fit to offer, and no more. On the other hand, a ship-model is full of life and rich in character. It can be moved about at will, examined from every angle, so that we can look down upon its decks or with the finger follow its underwater lines. We can see bow and stern, broadside and topsides; in imagination we can go aboard and take her to sea. With such a model confronting us we read of voyages and sea-fights almost as if we were members of the ship’s company, so that a new living spirit breathes through the past and all mustiness is banished from history, It is not surprising, therefore, that many eager persons to-day spend every spare moment studying models in the public collections, carving models for themselves, displaying them at annual exhibitions and competing for prizes.

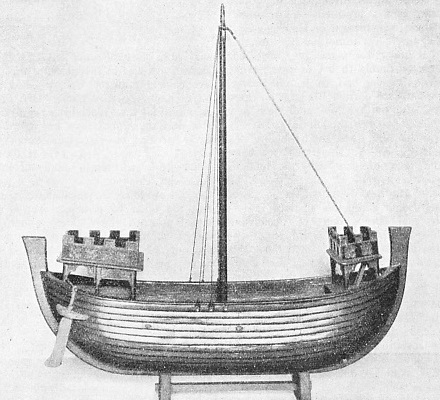

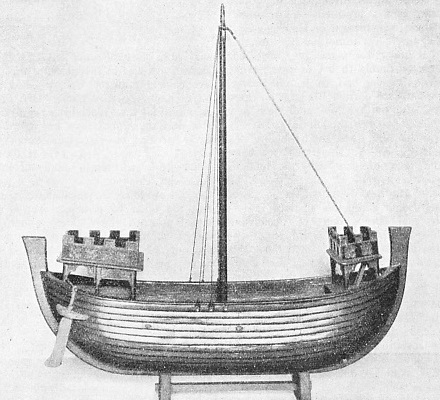

A MODEL OF A LATE THIRTEENTH-CENTURY VESSEL used to transport English crusaders to the Holy Land. This model was made by Mr. G. F. Campbell, and the reconstruction was aided by the study of the Winchelsea and Sandwich Seals. The original ship would have measured 73 feet long, 19½ feet beam, with a depth of 9 ft 7-in. The mast would have risen 58 feet above the deck and set one large square sail.

National and municipal nautical museums have been completely overhauled and rearranged, and others have come into being. Not merely in London, but also in Liverpool, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Hull, and other parts of the British Isles; also in Paris, Dunkirk, Amsterdam, Rotterdam and Madrid; and in various towns of Germany and Scandinavia, such collections are now given proper care and attention. From lumber-rooms of private houses and dusty attics many a long-forgotten and disordered little model has been taken, treated with reverence, repaired, re-rigged in accordance with unquestionable data, and restored once more to life.

Not many years ago such faithful restoration would have been impossible. Most of the genuinely old hulls had been re-rigged and re-sparred during the eighteenth, nineteenth and early twentieth centuries not in accordance with the appropriate period, but with the rigger’s own personal seagoing experience. Thus Stuart models, after much neglect, were altered to resemble early Victorian East Indiamen as far as insincerity could permit.

We may divide all ship-model s into three classes: (a) those which are old and represent the vessels of their period; (b) modern representations of old ships; (c) contemporary models of the shipping of to-day. These last two sections may be subdivided. They may belong to the “show-case” category - that is, perfect examples of beauty and instruction and never taken out of their glass case. Or they can be made practicable - possessing the virtue of sailing on the water - while not forfeiting their claim to technical accuracy. By way of introduction to the study of this fascinating subject, it has been decided to include illustrations of each division, and with these we shall presently deal more precisely.

In the whole story of our subject there is a line of demarcation which occurs about the mid-sixteenth century. With few exceptions, all ship-models from early Egyptian times down to the Reformation, that is, a period of approximately 6,000 years, were chiefly made with some religious motive.

But after the mid-sixteenth century the stream divides. In such areas as Spain, Brittany and other Catholic maritime countries, we find model boats and ships placed in churches as votive offerings; even the receptacles for incense are shaped in the form of a boat and are given the name of a boat or naveta. There exists, for example, in the Madrid Naval Museum a fourteenth-century naveta with rounded bows and square stern similar to those of a contemporary medieval ship. Tourists who visit Burgos will find a still more elaborate specimen in the Capilla del Condestable. So, also, in many a French port from the north coast to the Mediterranean will be found - sometimes hanging from the roof, sometimes mounted in glass cases - models of modern fishing craft and coasters, placed there as some votive offering after anxious crews have come through gales of wind.

In such countries as Great Britain, Sweden and Holland, the Reformation generally banished these model craft so ruthlessly that most of them were destroyed. With them passed some of the most priceless ship records, though it is interesting to note that a reversion of that policy has taken place within recent years. In Southwold (Suffolk) parish church new sailing models are now hanging from the roof, and a Southampton church contains a beautiful model of a liner.

Queen Elizabeth had not died before Phineas Pett, member of that illustrious family which for generations did more than any other for English ship-building, was making the earliest official ship-models ever produced in this country. From then onwards we have a not quite continuous practice which persisted also in Holland as well as in France and the Baltic states. Sometimes the motive was to provide a guide for the builders themselves, sometimes to excite the monarch’s enthusiasm. On other occasions the reason was to let the potential owners obtain an adequate idea of the full-sized vessel. There were also times when all this careful work was carried out as a present for some distinguished personage.

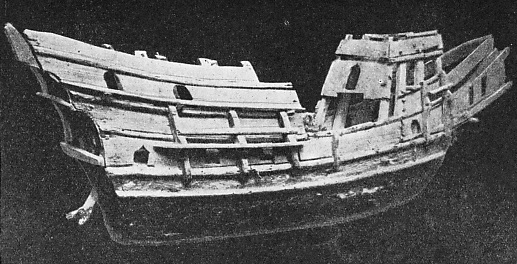

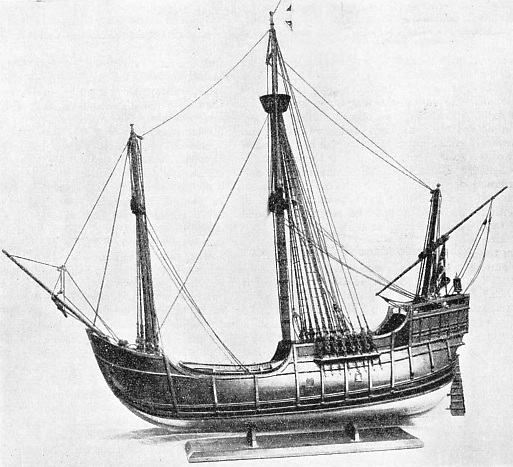

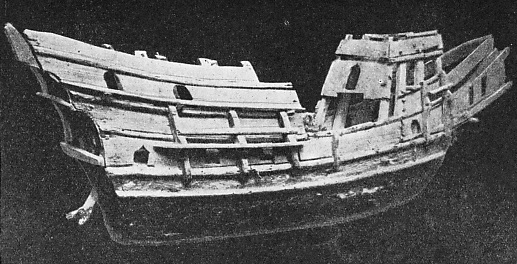

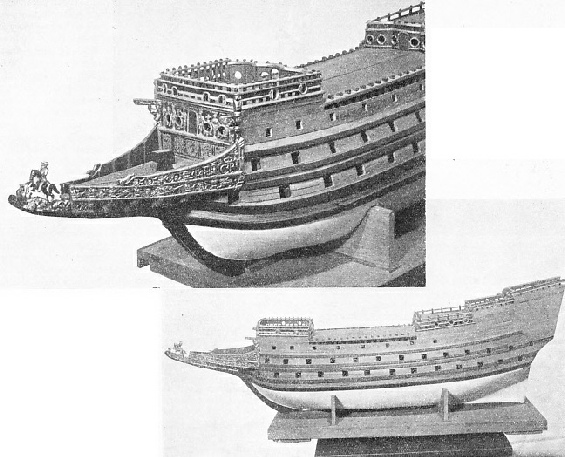

Spain possesses two of the oldest and most interesting models that survive from the sixteenth century. And first, let us call attention to the hull of a Spanish galleon dated 1540, or nearly fifty years before the Armada. (See illustration below). Some readers may not see much beauty in this votive model, which in the course of centuries has come down to us without masts or yards. Yet the details of the stern and forecastle, the short waist, the long halfdeck, the wales and rubbing strakes - exaggerated though they may be - will be valued by many a ship-lover. To examine this illustration alongside those of galleons seen in sixteenth-century maps and prints is to provide artists, students and model-makers with genuine facts. It gives a true picture that differs vastly from some of those fantastic sketches in school-books purporting to illustrate Tudor history.

DATED 1540. Spain possesses two of the oldest models that survive from the sixteenth century. This is the model hull of a Spanish galleon of 1540 which gives the ship-lover some authentic details of the vessel of that period. This valuable antique is now in the Madrid Naval Museum.

DATED 1540. Spain possesses two of the oldest models that survive from the sixteenth century. This is the model hull of a Spanish galleon of 1540 which gives the ship-lover some authentic details of the vessel of that period. This valuable antique is now in the Madrid Naval Museum.

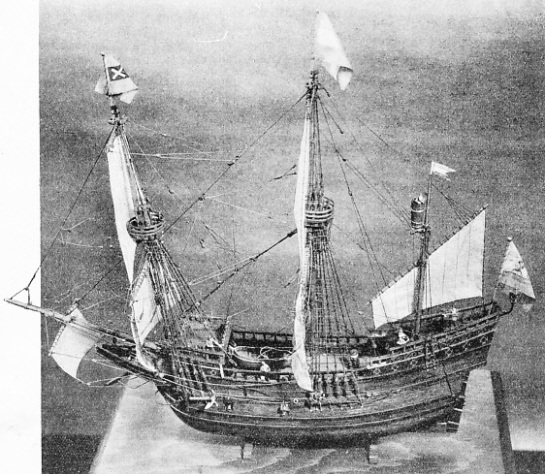

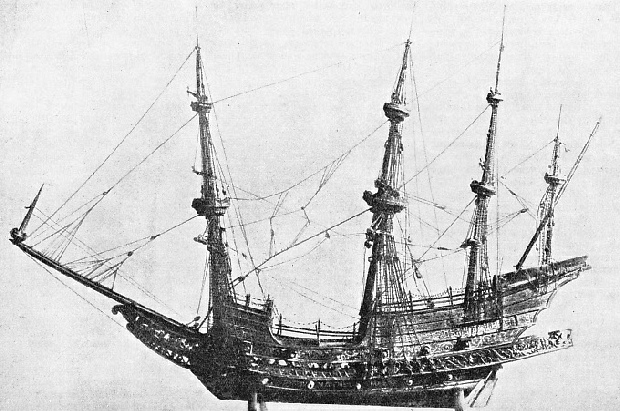

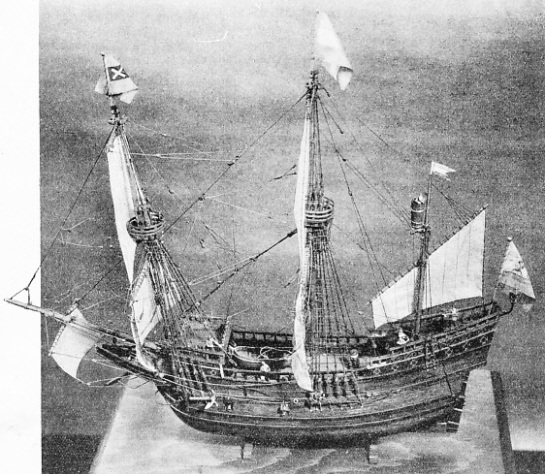

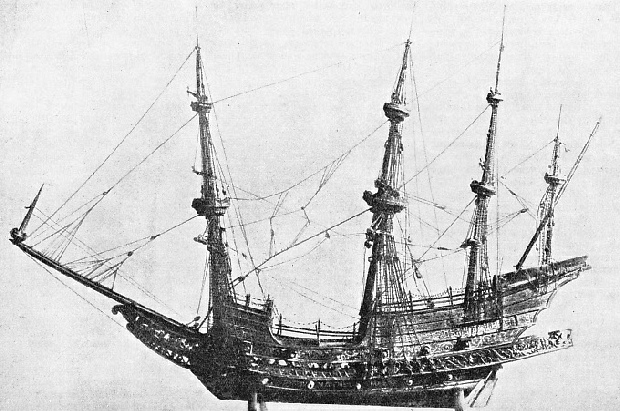

This early model, which is in the Madrid Naval Museum, may be a rough job, but at least it is the creation of a seafarer and not of a landsman. But the finest contemporary model of a four-masted galleon, such as sailed between Spain and Flanders, is also preserved in the above collection and here reproduced below. Dating from 1592, when Queen Elizabeth still sat on the English throne, this Flemish man-of-war is one of the most interesting ship specimens extant. The hull in its general features finds confirmation if we compare it with the prints of that date. But all the wealth of detail, and the actuality, belong to the model rather than to the picture. Here is a splendid opportunity for our amateur ship-model societies. It should be a joy to copy the galleon’s hull, and at the same time to take advantage of modern research. For the raking of the masts is not unauthentic, and such characteristics as the position of the foremast, the forecastle, the long projecting beak, the “tops” on the masts, the lengthy half-deck and short waist are all above criticism; yet the rigging needs considerable revision. Patience, skill and technical knowledge derived from sound sources could combine to produce an enviably improved replica.

SIXTEENTH-CENTURY FLEMISH GALLEON. This wonderful model, dated 1592, is to be seen in the Madrid Naval Museum. Its wealth of accurate detail makes it of special interest.

There survive a few old hanging ship-models in northern Europe, of which some are still suspended from the church roof, as in the Dutch waterside church at Haarlem. Others are to be found in German and Swedish museums. Of the latter we could desire no more illuminative specimen than that (illustrated below) from the Maritime Museum, Gothenburg. This indicates the rigging of main and mizen masts of a Danish votive model that used to hang in a Swedish church near Gothenburg in the early eighteenth century. It would be difficult to find more thorough information concerning the deadeyes, tops, blocks, halyards, rigging, lateen yard, lead of the main-braces and so forth.

If these three photographs be accepted as showing what can be learned from old and contemporary patterns, we can next proceed to the replicas of bygone vessels, as the present generation views them. Apart from stained glass windows, and the seals of such ports as Dover, La Rochelle, Hastings, Winchelsea, Sandwich and a few other sources, pictorial data of medieval ships are somewhat scant. Illustrated on this page is a model of a late thirteenth century English crusader, made recently by an amateur craftsman, Mr. G. F. Campbell. This modern reconstruction was rendered possible after much research, and by relying largely on the Winchelsea and Sandwich seals. Although here seen only partly finished, we have a clinker-built vessel that would have measured 73 feet long, 19½ feet beam, with a depth of 9 ft 7-in, for carrying to the Holy Land both horses and men. The mast would have risen 58 feet above deck, and set one large square sail. The bulwarks would have measured 3 ft 9-in high, the castles (used as fighting platforms) at bow and stern having been decorated in red and yellow. The hull itself remained oak-coloured, but black-pitched below the waterline. Built to the scale of ¼-inch to one foot, this model well shows the Viking influence, even to the rudder at the stjornbordi or starboard side.

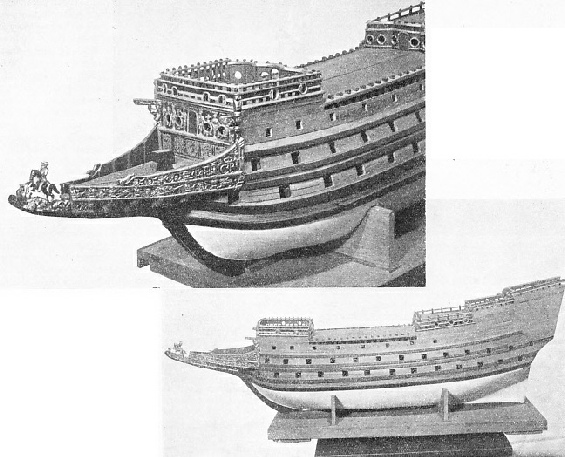

One of the famous sailing warships was the Soveraigne of the Seas, built by Pett on the Thames-side in 1637. Peter Mundy, who lived in London at that time, has left us a delightful account of how he travelled down in a 7-tons sailing craft one winter’s morning from Billingsgate to Woolwich. Here he landed to behold “the great shipp now on the Stocks a building in Woolwich Docke, where Mr. Pett the younger, Cheife Carpenter or Artist, shewed and related what hee desired to see.” After having looked at this 1,522-tons vessel, Mundy was taken into Pett’s house “where we sawe the Modell or Molde of the said shipp, which was shewne unto his Majestie before hee began her. The said Modell was of exquisite and admirable Workemanshipp, curiouslye painted and guilte with azur and gold, soe contrived that every tymber in her might bee seene, left open and unplancked for that purpose, verye neate and delightsome. There were also the Modells of divers other shipps lately built, but nothinge comparable to the former.”

Now the Soveraigne of the Seas has in recent years inspired the ablest modellers both in England and America, because of her impressive beauty and decoration. Mundy called her “the greatest and fairest that ever was water borne of English built.” Measuring 145 feet along the keel, she was more impressive than useful, and a source of great anxiety to her officers. Blake, in reporting the battle of the Kentish Knock, mentioned the narrow escape the vessel suffered through getting ashore during that engagement. She “began to stick, but, blessed be God, . . . got off again.” The abnormal high weights of her upper works and guns made her so crank (liable to list or upset) that eventually she had to be cut down. Originally she carried 102 guns on three tiers, and on her fore and main flew royals above her topgallant sails.

THE SOVERAIGNE OF THE SEAS a 1,522-tons vessel built in 1637 on the Thames-side was one of the most famous warships of her day. The pictures here illustrate a fine though unfinished model of this ship. The upper picture shows the beak ending with a figure of King Edgar (A.D. 944-75) riding down his foe, also the remarkable amount of decorative work typical of Stuart ship-building. The ship measured 145 feet along the keel and originally carried 102 guns in three tiers.

In the unfinished model before us, made by Mr. V. H. Green, we have some idea of how ably a modern representation of an old ship can be done The beak ends with a figure of King Edgar riding his enemies underfoot, and the amount of decorative work - so loved by Stuart shipbuilders - here means for the modeller considerable toil spread during odd hours over several years. Even as we examine the bare, planked hull, without even masts or yards, we can well appreciate Peter Mundy’s cause for admiration; we can understand why during the late seventeenth century the practice of building a model, to show the future owner what he was about to possess, became well-established.

The Navy Board again emphasized this rule in the year 1716. It is partly because of such regulations that so many contemporary ship models still survive in our public and private collections. So also in seventeenth-century France the minister Colbert used to have exact dockyard models of a warship built for the French king’s scrutiny. Nor were these mere toys, but as much as 30 feet long, full-rigged and canvased, so that they were sailed on the water at Versailles with a crew of seamen aboard. Although this somewhat extravagant method of aiding the royal imagination may be open to criticism, the little vessel afforded the builders a perfect design, showing the exact shape and position of timbers, arrangement of decks, masts, rigging and balance of sails.

After all, this detailed effort does not in principle differ so much from the making of those paraffin-wax models used to-day in experimental tanks when a large liner is being designed. The science of naval architecture now is infinitely more wonderful than anything that the Pett family could have conceived. Nowadays the experimental tank enables the designer to improve a ship’s underbody lines by movement through the water, and to continue testing until the hull-shape cannot be bettered. Reference may be made to the chapter “How the Modern Ship is Tested” (see page 27). Even the Round Pond in Kensington Gardens, with its weekly sailing matches of model yachts, has afforded some valuable data applicable for cutters that race in Cowes week.

After all, this detailed effort does not in principle differ so much from the making of those paraffin-wax models used to-day in experimental tanks when a large liner is being designed. The science of naval architecture now is infinitely more wonderful than anything that the Pett family could have conceived. Nowadays the experimental tank enables the designer to improve a ship’s underbody lines by movement through the water, and to continue testing until the hull-shape cannot be bettered. Reference may be made to the chapter “How the Modern Ship is Tested” (see page 27). Even the Round Pond in Kensington Gardens, with its weekly sailing matches of model yachts, has afforded some valuable data applicable for cutters that race in Cowes week.

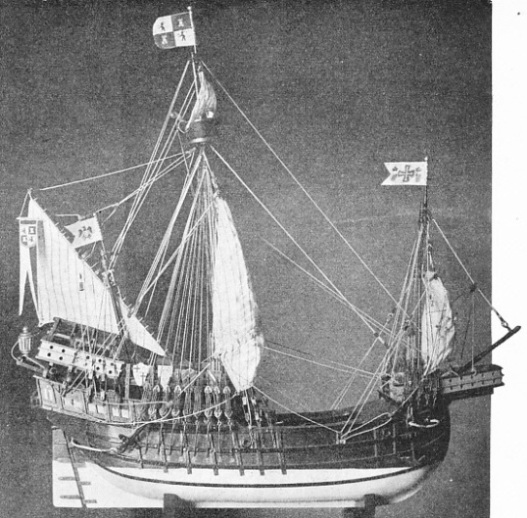

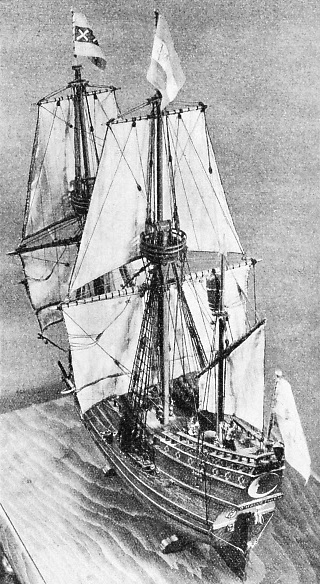

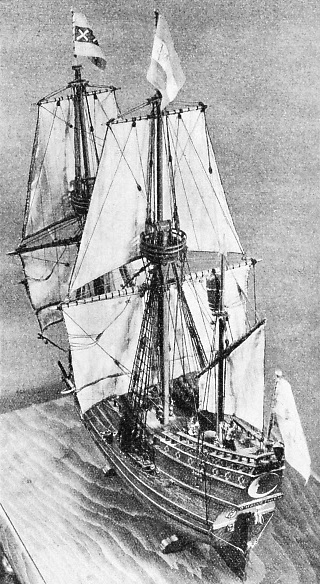

AN HISTORIC VESSEL—the D’Halve Maen. A model of Henry Hudson’s ship which sailed from Holland in 1607 to search for the North-East Passage to the Indies for the United Dutch East India Company. The perfect model shown above of the three-master was completed in 1930 by Mr. G. E. Crone of Amsterdam, a recognized authority on Dutch shipping of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. It is now in the possession of the Phillips Academy, Andover, Mass., U.S.A.

But the finest instance of profound and accurate historical knowledge being combined with reproduction belongs to Hudson’s Half Moon, a vessel that is only slightly less memorable than Columbus’s Santa Maria and Drake’s Golden Hind. The Half Moon is worthy of mention in the same category as the pilgrim ship Mayflower, one of her contemporaries.

The sequence of our story is unusually interesting, and begins in the year 1606, when a number of English people started off down the Thames, arriving a few months later on the North American continent. There they made a plantation in Virginia. Among them was that great character, Captain John Smith, one of the outstanding names in colonization. In 1609 a ship called the Mary Margaret brought home in duplicate from Virginia a “Mappe of the Bay and Rivers”. This survey had been made by Smith for the London merchants who financed the expedition, but the duplicate was for that other English discoverer, Henry Hudson, and the present had an important result.

The Dutch East India Company at that time was anxious to find the North-East Passage to the Indies, and entered into a contract with Hudson to that end. A three-masted 80-tons ship named D’Halve Maen (or Half Moon) was fitted out, and left Holland. But, after reaching a point beyond the North Cape - in the north of Norway - Hudson decided to go no farther north-east in his quest. Despite his employers’ orders that should he give up the attempt he was to return immediately to Amsterdam, Hudson could not resist the temptation which America held out. Surely Smith’s “mappe” suggested that the Passage would be found rather in the north-west than the north-east?

Hudson turned west and sailed past the Faeroes, Newfoundland and Nova Scotia. Early in September he was exploring the river that still bears his name, and landed on the spot where a few years later the first Dutch settlers were to found New Amsterdam - later New York. If Hudson failed to discover the Passage that for centuries was to attract so many plucky explorers, he certainly won fame by this pioneer voyage both for himself and for the Half Moon. In November the Half Moon crossed the Atlantic again and sailed into Dartmouth - no small achievement for so small a ship during the boisterous autumn ocean gales. From the Devonshire port the Half Moon reached Holland, whence two years later she sailed out to India. There she ended her days by fire in 1618. It was but two years afterwards - in 1620 - that the Mayflower left Plymouth with her Pilgrim Fathers, passengers for New England.

In 1909, when the United States were having their Hudson-Fulton celebrations, the Dutch city of Amsterdam presented to the people of New York a full-size replica of the Half Moon; but, as we have already emphasized, that was a period when naval archaeology was still lacking many enthusiasts, and the gift unfortunately contained anachronisms. But in 1921, Mr. G. E. Crone, of Amsterdam, now universally recognized as one of the greatest authorities on Dutch shipping of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, began to use his vast and detailed knowledge in the making of a new model.

PRINTS, PICTURES AND DOCUMENTS of Hudson’s period were carefully examined before Mr. G. E. Crone made this wonderful model of the Half Moon. The painted decoration of the lower part of the upper planking is light or dark blue, the upper part green on red. The counter is light blue bearing the arms of Amsterdam, three white St. Andrew crosses on black, with red on either side. The arms are also on the stern flag with their supporting lions; on the foremast are the same municipal colours. At the main is the red-white-blue Dutch flag with the monogram of the United East India Company.

With one assistant he set to work and, after twelve months’ delicate painstaking, produced the Half Moon - a fine achievement. Not entirely satisfied with its accuracy, Mr. Crone, again with scrupulous care, addressed himself to the same subject, and in 1930 completed the Half Moon model illustrated on this page. It is now in the possession of the Phillips Academy. Andover (Massachusetts). If Henry Hudson could come back to life the discoverer would be the first to acknowledge the extraordinary correctness of every tiny item. Reliable prints, pictures, and documents of Hudson’s period were all carefully examined for precise data, even to the costumes of the crew. The prototype measured about 63 feet between stem and sternpost. The painted decoration of the lower part of the upper planking is light blue or dark blue, the upper part being green on red, and the stern decoration shows a half-moon with (below) the words “D’Halve Maen”. The counter is light blue and bears the arms of Amsterdam, consisting of three white St. Andrew crosses on black, with red on either sides. The same arms with their supporting lions appear in the red-white-blue flag at the stern. Flying from the foremast are the same municipal colours, and the red-white-blue Dutch flag is at the main, with the monogram “V.O.C.”, meaning in English “United East India Company”.

The six sails are absolutely correct, and even the five men are excellent bits of characterization. High up on the mizenmast in the crow’s-nest is the look-out man ready to hail the deck. On the poop will be seen the pilot with his cross-staff for observing the ship’s latitude; on the half-deck stands Hudson himself. Those readers who may wish to begin a study of ship models, or to collect illustrations of undeniable accuracy before trying to conjure up the vessels which made history, might well spend some time examining a multitude of items here presented. In the rigging and lead of the ropes - the stays, braces, ratlines, crow’s-feet and other technical nautical details - are displayed more delving and constructive toil than will be recognized except by model-makers themselves.

Not unnaturally numerous models purporting to represent Columbus’s Santa Maria have been made by all sorts of people in recent years, and with varying success.

The “Santa Maria's” Measurements

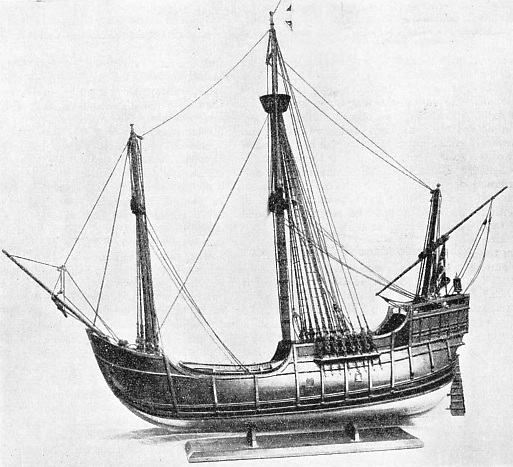

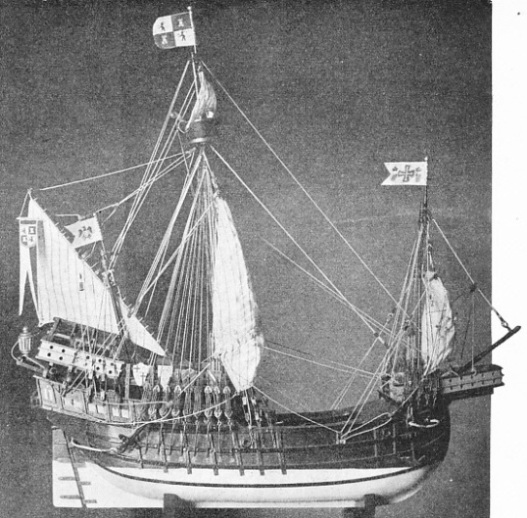

In the world-famous Science Museum, South Kensington, there is preserved a singularly beautiful piece of craftsmanship that was given to the British by the Spanish Government in 1923, copied from a model of the Santa Maria, made during 1892, in the Madrid Naval Museum. This model, in turn, had been constructed from information found in contemporary documents. Unfortunately a number of inaccuracies have been allowed to creep in, such as those relating to the ratlines, the bob-stay and the mainstay. In the year 1927 Captain Julio F. Guillen, Director of the Madrid Naval Museum, constructed a fresh model with a round stern, no bobstay, and the mizen yard quite rightly composed of two parts lashed together, as had been the seafaring custom for centuries. It is by Captain Guillen’s courtesy that this interpretation of the Santa Maria is illustrated on this page.

But still more modern is the recently finished Santa Maria by Mr. E. V. Michael, which is a beautiful piece of work and constructed to scale. It will be noticed that no mistake of ratlines has here been made. But it is doubtful if a quite correct Santa Maria, of unquestioned accuracy in all her details, could nowadays be fashioned. We know that she was a trading carrack, but her length of hull (between stem and stern-post) has been variously estimated from 74 to as much as 86½ feet, and her supposed beam was anything from 25 to 27½ feet. Her displacement was fewer than 250 tons. According to information which has been sent to me recently from Spain, she drew about 10 feet.

RECENTLY FINISHED. A beautiful model of Columbus’s ship the Santa Maria, made by Mr. E. V. Michael. This model has been constructed to scale, and the details of her rigging and other features are as near perfect as possible.

As to what a medieval carrack did look like, we are thrown back for trustworthy information on such details as are found in Carpaccio’s well-known painting, “The Departure of St. Ursula”, and the famous print by that Flemish master who signed himself “W. A.”, supplemented by a few other details. So it will be seen that he who devotes his spare time to making bygone ships come to life has chosen one of the most fascinating hobbies - not a temporary indulgence in mere amusement, but the provision of something that has permanent value.

It will be found in practice advisable to select one special period of seafaring, or one particular vessel, rather than to begin with the oldest and then work down to modern times. If, for example, the Santa Maria be chosen, then a great delight will be taken in reading the contemporary accounts of Columbus’s voyages and his own diary. From these we obtain all sorts of illuminating items concerning the life on board. We can see the crew bringing their salt meat, bacon, live lambs, calves heifers, biscuit, corn and wine for the long voyaging , we can learn that in a favourable wind the speed of these late-fifteenth century ships was about 100 miles a day, and that the distance from the Canaries to the West Indies, when the Trade Winds were used, could be covered in about a fortnight.

But those enthusiasts who are fortunate enough to live within easy distance of some lake, reservoir, or sheltered still water may prefer to concentrate on making practicable models of full-rigged ships, barques, modern topsail schooners or Brixham or Lowestoft ketches, and trying them out afloat. One busy amateur spends the winter making these models to scale, and in such a manner that they can be unrigged, packed up, taken to the nearest sheet of water, rigged, and then sailed. For years he has had any amount of amusement during the summer, working a rowing boat towards the model, photographing it under reefed canvas in conditions that proportionately would mean heavy weather for a real ship. The photographs are amazingly lifelike. There could scarcely be a happier combination of indoor recreation and outdoor sport. And the cost need not be anything but modest.

A model of the three-masted full-rigged Ightenhill, the work of Mr. W. Lewis, sails in the most lifelike manner. This little vessel is a working model measuring 4 ft 3-in overall. She is fitted with the maker’s own patent winch for operating all the braces and allowing quick adjustments when racing. Such ingenious craftsmen can create much out of little, as do clever chefs. Thus, geared steering can be obtained by using old watch wheels, and pumps and windlasses are made of other odd bits and pieces; and deck-houses can be made of discarded rubbish.

One of the most convincing working models - and perhaps the largest of recent years, reminiscent of the previously-quoted Colbert tradition - was that which was built up, rigged and sailed not long ago by Admiral Sir T. Spencer Lyne when he was commanding officer of the Impregnable Training Establishment at Devonport. This model of the old wooden H.M.S. Impregnable was made out of a 40-ft naval sailing pinnace, on which the hull had to be built up. For this purpose scantling and canvas were used. Ballasted with capstan-bars stowed under the thwarts and capable of adjustment, the Impregnable was handled in proper seamanlike manner and caused a sensation in Plymouth Sound. Her crew generally consisted of Admiral (then Captain) Lyne, twelve boys and boatswain. She could carry full sail in a fresh breeze, and would reach to windward, lying about five point-from the wind. During a moderate breeze she rarely missed stays and gave much pleasure during the summer months, as well as providing nautical education. She used to visit all the local regattas near Plymouth.

Flying the White Ensign, she slipped along with marvellous similarity to a big ship. “I got a bit anxious on one occasion outside Plymouth Breakwater,” Admiral Lyne has said, “when a bit of a squall caught us.” He relates the following anecdote. “We carried two saluting guns and were very generous with them to departing guests. On first meeting with the Commander-in-Chief under way, in accordance with time-honoured custom, we dipped the royals and gave him seventeen guns. The Commander-in-Chief stopped engines and remained uncovered, much impressed!” If one generation has the responsibility of handing on its inheritance, it is surely a pleasant task to leave behind authentic, detailed models of modern types which for a little while seem ordinary but presently will be regarded with curiosity and awe.

THE SANTA MARIA, a model of Christopher Columbus’s famous ship. Numerous models have been constructed of this vessel, but the exact dimensions of the original ship are not known. Her length of hull has been variously estimated from 74 feet to as much as 86½ feet, and her supposed beam was anything from 25 to 27½ feet. Her displacement was under 250 tons.

You can read more on “At Sea in the Middle Ages”, “Marine Models”, “Ships in Postage Stamps” and “The Sovereign of the Seas” on this website.

DATED 1540. Spain possesses two of the oldest models that survive from the sixteenth century. This is the model hull of a Spanish galleon of 1540 which gives the ship-

DATED 1540. Spain possesses two of the oldest models that survive from the sixteenth century. This is the model hull of a Spanish galleon of 1540 which gives the ship-

After all, this detailed effort does not in principle differ so much from the making of those paraffin-

After all, this detailed effort does not in principle differ so much from the making of those paraffin-