© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

From Tudor to Victorian Times

A survey of life at sea in British ships from the close of the Middle Ages to the accession of Queen Victoria. During this period seamanship gradually improved and the men-

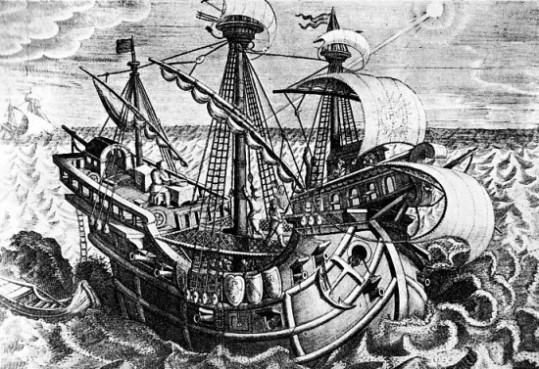

LIFE IN AN EARLY SHIP is illustrated by this sixteenth-

IT was Henry VII (1457-

His navy list comprised a dozen royal warships, including the four-

The invention of gunpowder, which had been coming into use ever since the mid-

The use of these guns was tactically quite different from twentieth-

All those superstructures of poop, poop royal, forecastle and summercastle so overburdened the ship that she was difficult to handle and made considerable leeway. The nearest such ships would sail to a wind was seven points, and the only way to do anything with them was to keep them ramping full with fair wind and tide. Most naval stores had to be fetched from Genoa, Italy, though canvas was beginning to be made in England.

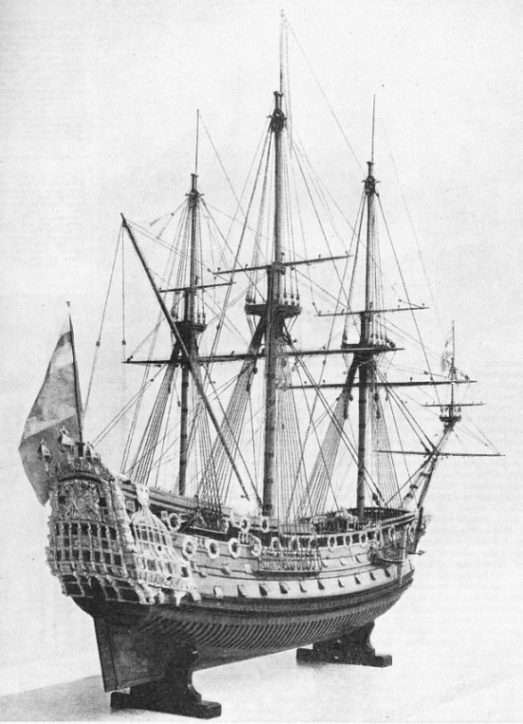

LAUNCHED AT CHATHAM in 1670, the Prince was a first-

The cut of Tudor sails provided mere windbags, and the Dutch were the best sailmakers down to the time of Charles II. Thus it is not surprising that ships used to get ashore among the Thames Estuary shoals when making for the River Medway or bound for the English Channel. Going to sea was exceptional and not normal. From mid-

The increase of tonnage added to the difficulty of manning. Although the Sovereign had no hard task in finding 400 soldiers, she could not easily obtain her forty gunners and 260 sailors. The sailors were needed for handling sheets and braces, for going aloft, making sail, steering and so on. Their pay was 1s. 3d. a week with victuals. The cost of food worked out at 1s. to 1s. 2d. a man weekly. The contract was allotted to some person whom the King wished to reward, and

there were many opportunities for selfenrichment at the crew’s disadvantage. Bread, biscuits, beer, barrels of herring, oxen, salt for powdering the beef, peas, wood for the galley fire, and candles for the dim illumination were the main domestic items of perishable stores.

Hammocks had not yet been introduced among English sailors. They lay down and slept as best they could — on deck in fine weather and below when it was wet. Only the Captain and the Master had cabins, and they messed apart until later in the Tudor period when they ate together in the Captain’s “great cabin”. Regular uniform was unknown, but the King usually gave the men their coats.

Divided Responsibility

The ship’s organization was still — as it had been in Greek or Roman triremes — military rather than naval. Thus the commanding officer was a soldier — a Captain who knew a good deal about fighting and was expected to be a disciplinarian accustomed to handling men or leading an expedition. His technical knowledge of seafaring generally was ml. Under him was the Master, who received 3s. 4d. a week and served as the officer in charge of boatswain, purser, gunner, quartermaster, steward, cook and sailors. The Master was responsible for the ship as a means of transport, but the navigation belonged to the pilot and the Captain looked after the soldiers. It is scarcely surprising that for generations there existed much friction between the unseamanlike Captains and the unmilitary Masters.

The Tudor ships had their seams caulked with oakum, flax and hair, mixed with pitch and tar. When voyages of discovery began to be made to the tropical seas of West Africa, the West Indies, or Brazil, where the shipworm did untold damage, it was customary to sheathe the underwater portion of a ship’s hull. Half-

These vessels looked picturesque with their pavises on poop and in the waist. The pavises were made of poplar wood, painted with coats of arms and heraldic devices, many-

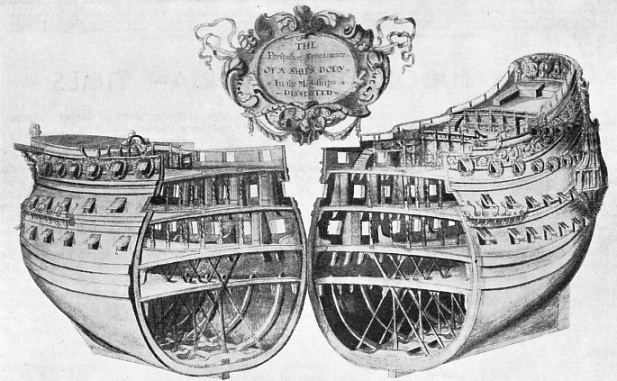

A SECTIONAL DRAWING, or, as the draughtsman notes, “The Perspective Appearance of a Ship’s Body In The Mid-

The royal bounty on the building of new merchant ships was a far-

A series of good catches off the southwest English coasts enabled the smallboat men to build a few larger craft and go out to the Newfoundland Banks, bringing back wealth and experience to Plymouth. Grandsons of men brought up to haul a few lobster-

To men of imagination the sea has always signified wealth. Was not Amsterdam said to have been erected on the bones of herrings? When once inshore fishing gave way to deep-

From peaceful green creeks and picturesque cottages of the Rivers Dart and Tamar, young men of vigour and burning optimism went off with fathers and uncles to bring home those very commodities which would banish their prevailing penury most thoroughly.

Gradually famous naval families were being founded, whose members would rise to become admirals and win unending renown in the clash of battle.

John Hawkins, who was born at Plymouth in 1532, is typical of one who never had the smell of the sea out of his nostrils or the sight of a ship beyond his gaze. Between the ages of twenty and thirty he. had already made a number of voyages down to the Canaries. His father before him had amassed wealth by trading to Brazil and Guinea. The reprehensible carrying of African slaves was regarded in much the same manner as the transport of cargoes of linen and wool taken outwards or hides, pearls, gold and silver which were brought homewards. When such enormous profits were available from the smallest capital, a good crew and sound ship, not all the threats of Spain

Could keep these enterprising mariners from venturing across the ocean.

EARLY EIGHTEENTHCENTURY WARSHIP. An interesting rigged model of H.M.S. Tartar. The ship was built in 1734 at Deptford, on the River Thames. This model, which is one of the few rigged models of the period, is in the valuable collection of the training ship Mercury. The Mercury lies in the River Hamble, Hampshire,not far from Southampton, and is under the control of Commander C. B. Fry.

We know from sixteenth-

Steering was done by a whipstaff attached to the tiller vertically, so that the helmsman could see just above the quarterdeck and note from the sails whether he was going too near the wind. The tiller itself was below his feet, the stern of a ship by this date having become much higher than the rudder head. Except for the fulcrum obtained by a whipstaff or tackle, and in the absence of the steering-

“Make Fast and Belay!”

Had we been on board, we should have heard the tramp of mariners at the capstan until the anchor was clear of the water. Then, as the ship began to gather way, “Haul, aft the aforesail sheet! Haul out the bowline!” for the ship’s head to pay off and sail on a wind. “God send fair weather! Make fast and belay!” the Master would remark. The hoisting would be done with “One long pull. One long pull — more strength to it! More strength!”

In Elizabeth’s reign the crew had already got “netting” (hammocks) in which to sleep. Drums and fifes, hautboys and cornets made music. There were also hobby horses and other “Maylike conceits” for the sailors’ amusement. They messed in fours, fives or sixes, every man and boy being allowed daily 1 lb. of bread and a gallon of beer. On flesh-

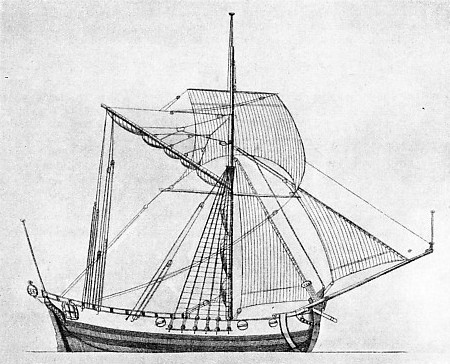

AN ENGLISH HOY OF 1717, from a contemporary drawing published in Sutherland's Shipbuilding Unveiled. Hoys were small cargo-

A cook was carried who had charge of the cans, platters, spoons and lanterns. The swabbers were responsible for washing and keeping the ship clean; but the first man found telling a lie was indicted of the offence every Monday at the mainmast and placed under the swabber to keep the latrines clean. Spanish ships were kept disgracefully — as one contemporary seafarer remarks, “like hogstyes and sheep-

On board the Elizabethan ships the Captain made his inspections twice a day to ensure their being kept sweet and clean against sickness; yet Tudor standards of cleanliness were considerably lower than those of to-

By the end of the sixteenth century the position was this: while Spain already owned rich colonies, England, although nationally poor, had shown by adventuring and tough fights that in her seamanhood, no less than in her ships, she could not be excelled by any other European Power. The English investors needed only someone to fire their enthusiasm for overseas trade and to fit out ships for long ocean voyages, to find markets which could consume English goods, such as iron, lead, tin and especially the thirteen different kinds of coloured cloth which were essentially national products. Now that the secret of a sea-

By the end of the sixteenth century the position was this: while Spain already owned rich colonies, England, although nationally poor, had shown by adventuring and tough fights that in her seamanhood, no less than in her ships, she could not be excelled by any other European Power. The English investors needed only someone to fire their enthusiasm for overseas trade and to fit out ships for long ocean voyages, to find markets which could consume English goods, such as iron, lead, tin and especially the thirteen different kinds of coloured cloth which were essentially national products. Now that the secret of a sea-

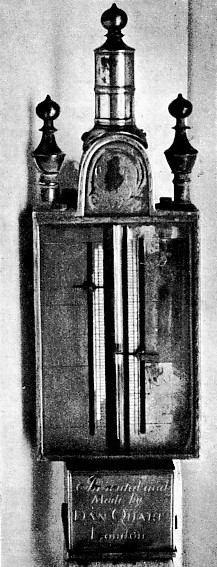

AN EARLY FORM OF BAROMETER. The instrument illustrated was used by Earl Howe in 1794, and was included in the “Admiral’s All” Exhibition at the Royal United Service Museum, Whitehall. Engraved on the barometer are the words “Invented and Made by Dan Quare, London”.

It was at this moment that the right inspiration was available. Richard Hakluyt became the expert adviser and great support, the tonic to drooping spirits, Jhe mental stimulant of the time; yet he was not a mariner in any sense of the word, but an intellectual cleric who could see far beyond the horizon of his contemporaries.

As a boy Hakluyt once visited the chambers of his cousin in the Middle Temple, and there was shown “an universall Mappe”, with certain books on cosmography. When his relative “pointed with his wand” to all the known seas, gulfs, straits, capes, rivers and territories, relating their respective trades, the lad resolved that if ever he should enter a university, he would pursue that geographical knowledge. Eventually he went up to Christ Church, Oxford, made a special study of voyages and discoveries, and later — in 1598 — published his famous collection which still makes most fascinating reading.

In 1599 a number of London merchants petitioned Elizabeth for permission to send four well-

An All-

Sir Thomas Smith became the first Governor (or Chairman) of the first English East India Company that, with variations and reconstructions, prospered right down to early Victorian days. To Hakluyt’s well of knowledge, filled from many sources, the original corporation went time after time to quench its thirst.

In spite of disappointments and set-

It was inevitable that, since jealousy is at the root of many squabbles, there should in the flow of time come the Anglo-

Only by a knowledge of the ships of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries can we realize the dangers and difficulties of the sea service. The English fleet which opposed the Armada had consisted of 197 vessels; thirty-

This list is fairly representative of England’s floating strength at the time when Spain’s 130 ships started out for the invasion. The two Elizabethan warships, Ark Royal (800 tons) and Triumph (over 1,000 tons), were representative of the builders’ largest effort, just as the famous Sovereign of the Seas (1,683 tons) was launched as the highest achievement for size during Charles I’s period.

MODEL OF AN EIGHTEENTH-

Nothing better illustrates the rapid development which had been made in less than a century and a half since the Middle Ages. From 1637 till the death of Nelson the progress in shipbuilding was comparatively slight, the differences being of detail rather rhan of principle. The reason is twofold. The Tudor period during its brief brilliance was full of mental vigour and adventurous originality, but the next centuries became conservative and imaginative until the nadir virtually coincided with Queen Victoria’s accession.

With the seventeenth century there certainly did come a widening of sea interest for personal careers. The nobility and “sons of gentlemen” were now being urged not “to think scorn” of entering this domain. There existed a prejudice, a snobbishness, against having a “tarpaulin” or merchant skipper in command of a royal warship, yet he might have made ten voyages to India and back and be much more of a sailor than the average captain in His Majesty’s service. On the other hand, the “tarpaulin” might have been pirate or privateer, and he might know nothing of fleet tactics; but neither officer, during that age of inferior moral standards, was normally untainted by dishonesty.

Perhaps the Pursers were at once the most tempted and the most guilty. For instance, their duties included receiving the ship’s food from the Victualler of the Navy and supplying the Treasurer of the Navy with the names of crews and dates of their admission, after which the men’s pay would be sent for distribution. A favourite falsification was for the Pursers to send up faked lists, so that in one particular year about £3,000 on board seven ships became converted. Thus names would be given of men who were not serving, had not yet joined up, or had been discharged. Even the name of the Captain’s dog would be written down as one entitled to draw pay. Another trick was for the Purser to charge a man for clothes which he had never so much as seen.

The average “common mariner” certainly hated serving in the Navy of the Caroline period, because he was generally there against his wishes: either he had no money or he had been impressed by the press-

Impressed Men's Grievances

The same opportunity occurred for merchant sailors when they used to man the ships that went out to Virginia. There the planters were only too eager for some brisk trading. But a serious grievance was found in regard to discipline. A sailor might join a privateer ship, where restrictions scarcely existed, and count on receiving, with his shipmates, one third of a captured vessel’s value, and enjoy a long riotous leave ashore. The impressed men, however, were brought to Chatham, Kent, never saw their families for long periods, and for perhaps three months at a time would never be allowed out of their ship, although she kept swinging round her anchors at the same spot in the Medway surrounded by the same monotonous scenery.

The regulation had been intended to prevent desertion, but in truth the more daring of these mariners used to wait for the various local rowing boats to come alongside after nightfall, lower themselves down, be landed on the beach, get drunk and wake up to find all their money gone. Having become sobered, they dared not go back on board, so they preferred to forfeit three months’ pay and be numbered among the deserters. At least they would not have to eat bad salt beef — scanty though the ration might be — or drink “infectious” water.

In the biggest of the seventeenth century warships were carried a chirurgeon (surgeon) and a minister of religion; but if the surgeon was incompetent, the chaplain too often was more interested in feasting and drinking of healths than in anything else. When in December 1606 the expedition of three ships left the Thames at Blackwall for the historical colonization of Virginia, most of the London tradesmen supplied the necessary stores at good prices; but “such juggling there was betwixt them” that they were able to palm off much trash.

DUTCH SEVENTEENTH-

It cost about £20 in seventeenthcentury money (about £200 to-

The ships used to drop down the Thames with the tide, anchor in the Downs for perhaps six weeks waiting for a fair wind, whence they made for the Canary Islands, where they replenished with fresh water. Using the north-

The royal men-

In the seventeenth century man-

Beneath the lowest deck, in the hold, was the Steward’s Room, with its stores of butter and cheese, the Bread Room and the Powder Room, with its barrels. The hogsheads of wine and butts of beer rested on the ballast.

Middle-

In the forecastle was the cook’s room, because this was a more convenient place than deep down in the ship, for the risk of fire and ruination of victuals by heat caused anxiety. The “jeer” capstan was situated between mainmast and foremast for hoisting the lower yards. The main capstan was farther aft, and was used for weighing the anchor.

If the vessel was overtaken by storm she would reduce to mainsail only; or run before the storm —“spoon” it was called — under bare poles. During flat calms and heavy swell, the Master was wont to take all canvas off her, so as to avoid damage to gear. When the wind blew just strong enough for her to carry topsails hoisted as high as possible, this was called a loom gale. When it blew so hard that some of the upper canvas had to be stowed, this was either a fresh gale or a strong gale. But when she could carry no sail at all it was blowing a tempest.

Even in the time of Charles I ships were well accustomed to using a logline (sometimes called a minute-

Seventeenth-

George II established a Naval Academy at Portsmouth for the improvement of young officers’ education, but it was an exclusive institution and languished in neglect until in 1806 it was raised to the dignity of a Royal Naval College. But the eighteenthcentury midshipman of the Royal Navy was often a man of low social standing, whose age might be as much as forty-

The ablest seamen for smart shiphandling undoubtedly were serving on board the collier and coasting brigs. Until well into Victorian times these seamen were veritable artists in working through narrow and difficult channels — such as threading their way between North Sea sandbanks or tacking up the Thames to London Bridge in spite of the traffic. These vessels could sail within six points of the wind.

Such crews could almost smell their way over the North Sea sands. They had a good deal of anchoring to do, and for this reason held the record of all ships afloat for windlass work. It was always found that whenever an ex-

But the ugly steam collier oi the nineteenth century gradually ousted these old brigs and fine seamen. So the era of genuine sailors was preserved in the clippers and full-

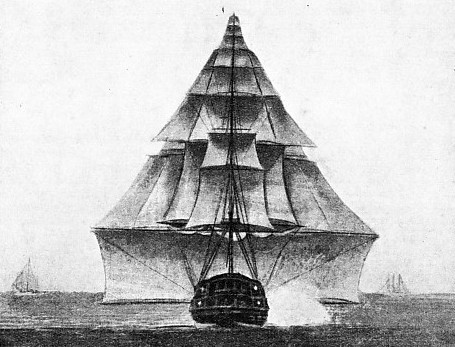

A RECORD SAIL-

You can read more on “At Sea in the Middle Ages”, “Life in the East Indiamen” and

“The Sovereign of the Seas” on this website.