© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

The Mississippi - “Father of Waters”

The romance of the Mississippi steamboats and show boats is not perhaps as great as it was, but hundreds of squat and elaborately decorated paddle steamers still ply on the muddy waters of the mighty river

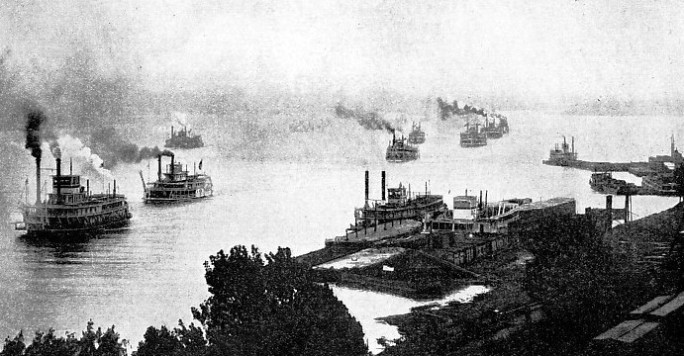

MISSISSIPPI STEAMERS serve one of the world’s greatest waterways. Although they have some characteristics common to most river steamers, the Mississippi boats have developed along lines of their own. Many are stern wheelers, some have screws working in tunnels, and nearly all have two slender funnels, often fitted with spark arresters, arranged forward.

READERS of the works of Mark Twain will need little introduction to the old-

To this day the white, swan-

The Mississippi is no ordinary river. It is not ordinary even by the standards of giant rivers, for it has a length of 1,192 miles from its source to where it joins the Missouri. In addition there are the 2,908 miles of the River Missouri above the confluence of the two rivers at Alton, Illinois, near St. Louis. Thus the combined length from the sources to the great delta in the Gulf of Mexico is more than 4,000 miles.

For a distance of roughly 1,150 miles the Mississippi meanders through a vast, flat, alluvial valley, in the northern part of which it is joined by the great River Ohio at Cairo. In this alluvial plain, floods are relatively frequent, for, although the river is banked by “levees” or earthen dykes, its

level is constantly rising, because of the silting up of the bed, and the bursting of the levee ensues almost as a matter of course. Below Cairo the maximum flood volume may be no less than 1,400,000 cubic feet of water a second, and it has been reckoned that in a year the amount of silt carried down to the delta below New Orleans would form a solid block of mud a mile square and 260 feet high.

It is not surprising, therefore, that such a monster as this performs prodigies at times. A tiny cut made in the levee at a point where the stream makes a broad sweep will change the whole course of the river in that neighbourhood within a few hours. Thus will be formed a large island surrounded on three sides by the old river bed and on the fourth by the new cut. On many occasions the river has in this way abruptly shortened itself by thirty miles or more.

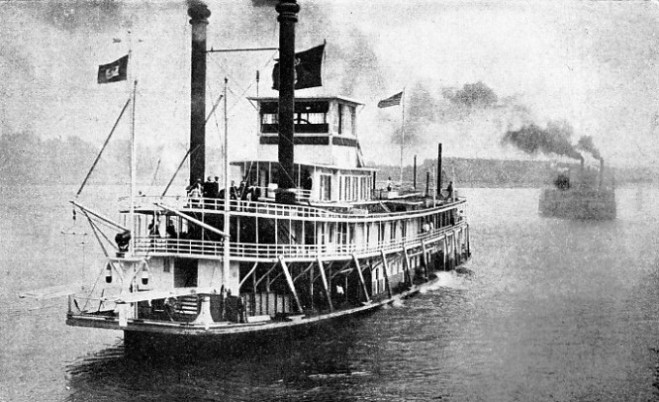

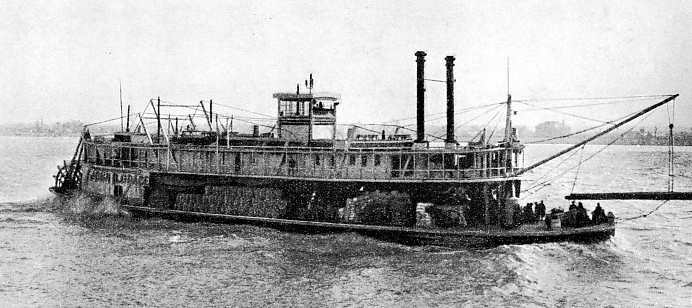

A RIVER STERN-

A classical example of this took place at Vicksburg, between New Orleans and Memphis. Vicksburg was originally situated on the river bank. The river suddenly changed its course, and now Vicksburg is up a navigable backwater. A far worse fate overtook the township of Napoleon many years ago. The town stood at the confluence of the Rivers Mississippi and Arkansas. The Arkansas undermined the town and within a short time swept the whole of it, with the exception of one small house, into the middle of the Mississippi.

Though efforts have been made to confine and canalize the vast river, it continues to choose its own course and to change its mind periodically. Of the town of Napoleon, Mark Twain said: “It was an astonishing thing to see the Mississippi rolling between unpeopled shores and straight over the spot where I used to see a good big self-

The site of Napoleon, however, has had its great days. For it was here, at the mouth of Arkansas, that the “Father of Waters” was first seen by the eyes of a white man, when the Spanish explorer de Soto stood at the confluence and watched the mighty coffee-

That was in 1542, when Henry VIII was still on the English throne and English colonization in America was a thing yet to come. Considerably more than a century elapsed before any further exploration took place. Then La Salle conceived the idea of rediscovering the reputed giant river. About the same time, Joliet and Marquette set off independently of La Salle, who had received a special commission from Louis XIV of France.

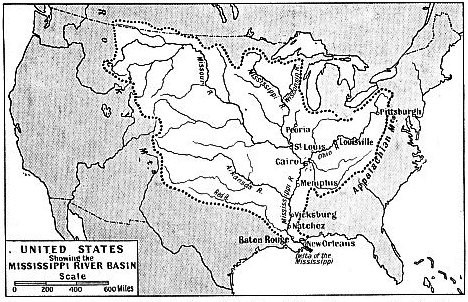

FROM SOURCE TO DELTA the Rivers Mississippi and Missouri have a combined length of more than 4,000 miles. The confluence of the two rivers is at Alton, Illinois, above St. Louis. The Ohio River runs into the Mississippi at Cairo. The Mississippi river system drains in all an area of about 1,250,000 square miles. The width of the river varies between St. Louis and Cairo from 650 feet to 4,000 feet at low water. From Cairo to the delta, the navigable channel has a minimum width of 250 feet and a minimum depth of 9 feet, although a depth of 35 feet is frequent.

Joliet and Marquette departed down the Wisconsin River in canoes, and reached the Mississippi on June 17, 1673. They had with them only five other men, but fortunately the native red men proved friendly after a few initial and rather alarming demonstrations. The object of this expedition was to find a new passage to China, the idea being that the Mississippi might possibly discharge its waters into the Gulf of California, and so afford a short cut to the Pacific.

The brave Frenchmen drifted down the river in the canoes, sleeping in them at night. Racked by hardship and tortured by clouds of mosquitoes, they persevered, and at last reached the confluence, where de Soto had stood more than 130 years before. For the second time the site of Napoleon became historic. The great inland voyage was completed without accident, and the explorers returned safely and triumphantly to Canada.

La Salle’s expedition did not get under way until the winter of 1681-

Once again the native tribes received the intruders with friendly demonstrations, and in the southern part of the valley there were found advanced Indian tribes living in brick-

“Fulton's Folly”

Nearly three-

Keelboat transport continued into the first part of the nineteenth century, and overlapped early steam navigation. The first steamboats at once monopolized the upstream traffic, but the keelboats continued to carry cheap freight downstream for approximately twenty years. The keelboatmen, having come down the river, would sell their craft in New Orleans, and return to the North as deck passengers in the steamers.

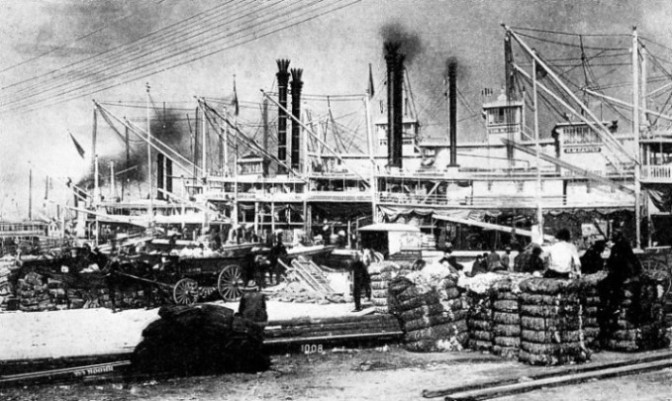

WHEN COTTON WAS LOADED a forest of derricks and smoke-

In the beginning of steam navigation on the Mississippi, Robert Fulton’s famous Clermont was apparently destined for those waters, for on August 17, 1807, the following quaintly phrased announcement appeared in the pages of the American Citizen: “Mr. Fulton’s ingenious Steamboat, invented with a View to the Navigation of the Mississippi from New Orleans upwards, Sails to-

Her maiden voyage, from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to New Orleans Was completed in fourteen days. In 1814 she made the run from New Orleans to Natchez, a distance of 268 miles, in the then astonishing time of six days six hours and forty minutes. Before the year was out, another steamboat, the Comet, covered the distance in five days and ten hours. That was the record for 1814. By 1870 the time for the passage had been reduced to a little over seventeen hours.

The real prototypes of the steamboats of later days were the Etna and the Vesuvius, which appeared in 1817. They were large vessels for the period, of 450 tons burden, with hold space for 280 tons of merchandise in addition to 700 bales of cotton. Cotton was one of the staple articles in Mississippi freights then and afterwards.

The Etna and the Vesuvius each had accommodation for a hundred passengers. Though the employment of steam began on the Mississippi only a few years after its first appearance on the Hudson River, marked differences between the Hudson and the Mississippi steamers were necessary from the first. In the total absence of other forms of passenger and freight transport (in the ’thirties, the only railway in the lower valley was a tiny feeder to the steamboats at Natchez), the Mississippi, Missouri and Ohio steamers had to be of large size with plenty of cargo space. At the same time, they had to draw the minimum of water.

Shallow Draught Essential

The river steamer that was evolved might be uncharitably described as a giant self-

The early steamers suffered badly from hogging and sagging under the strains imposed by the turbulent, muddy current, and, therefore, a system of stump masts, struts and iron ties was introduced by Colonel Stevens and applied to all vessels of this type built after the pioneer years.

Despite the American Civil War, the great days of the Mississippi steamers were during the 1850-

Imagine a great, flat-

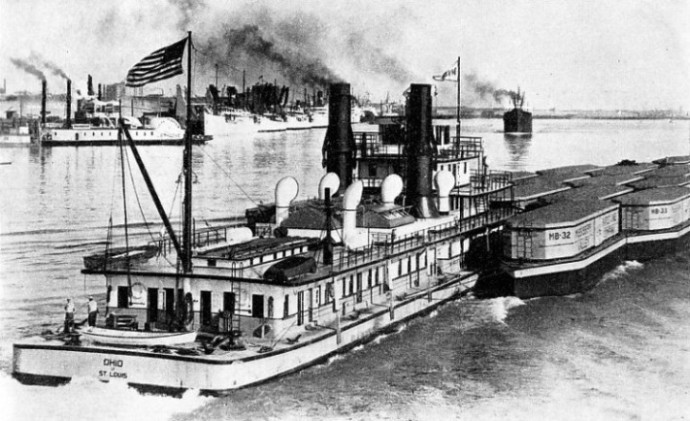

A MODERN RIVERBOAT pushing a new type of barge on the Mississippi at New Orleans. The Ohio, of St. Louis, belongs to the Mississippi Valley Barge Line Company, and has a steel hull, shallow draught and powerful engines. The barges are specially shaped at bow and stern to enable them to be packed together as closely as possible. Fitted into a mosaic pattern, they form one mass rather than a series of units. In the left-

Her upper works glisten with new white paint. The tops of her chimneys or smoke-

Extravagant decoration is one of her main features. If her paddlebox is not covered with complicated gilding and scrollwork, surrounding her name, it may be adorned with a huge coloured picture.

On board, oil paintings, executed perhaps with more colour-

The written word may suggest a merely barbaric note, and the black-

A great deal has been written at various times about the fast runs and hazardous races which took place on the Mississippi and its tributary streams in days gone by. Responsible writers have even gone to the length of blaming the racing fever for certain disastrous boiler explosions which took place now and then, ascribing these accidents to reckless engineers, who are alleged to have played dishonest and dangerous tricks with the safety-

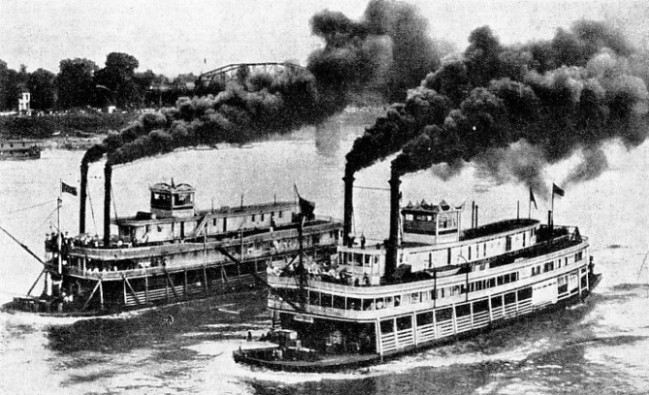

RACING ON THE MISSISSIPPI was once the subject of keen rivalries and great enthusiasm. Many famous races took place between Natchez and New Orleans, a distance of nearly 270 miles. The Sultana made this distance in nineteen hours forty-

Racing steamers, however, were kept in the finest possible trim, and boiler explosions were more frequently caused by the inattention of unhurried and lazy engineers, who let the water-

The first bad accident of this kind took place in the steamer Moselle in April 1838, during an exhibition run on the Ohio. The boat had gone a little way upstream from Cincinnati to create a suitably grand effect by ploughing back past the quays at full speed. Without any warning, the boilers exploded, blowing the entire vessel to fragments and killing more than a hundred people on board. Some estimates placed the death-

of the boilers, still more or less whole, shot up vertically to a great height, and came down as if it were a meteorite in one of the streets of Cincinnati, making an enormous hole in the road surface.

It is surprising what some of the steamboat boilers stood in the way of neglect and incompetent management without blowing up. We have firsthand evidence about one of the old Fulton steamers in which a boiler became not only completely empty of water but also red-

Although explosions were more the result of neglect than of excessive zeal during races, there is no doubt that acts of great recklessness took place in the early days of racing. About the same time as the disastrous explosion in the Moselle, a keen race took place on the Mississippi between the steamboats Pioneer and Ontario. During the race the Ontario purposely rammed the Pioneer. The amount of damage inflicted was slight, but the Pioneer was forced to drop back behind her rival.

Shortly afterwards, the Pioneer returned the Ontario’s unpleasant compliment. This time a passenger was killed by the crash, several were injured, and a great deal of material damage was done. Racing was forbidden for a while after this untoward incident, but it was impossible to stamp out the old enthusiasm for long.

A famous racing ground was the stretch from New Orleans to Natchez. The length varied round about 268 miles, according to the vagaries of the river. In 1844 the Sultana made this distance in nineteen hours forty-

In a great race between the Natchez and the Eclipse the tall smoke-

The American Civil War put an end to racing during the middle ’sixties, and to a great extent suspended all but the barest emergency traffic on the river. Steamers were commandeered as gunboats, and battles by land and by water raged along the banks of the river. At Vicksburg (Miss.) there is a monument to 16,000 men who fell in the fighting.

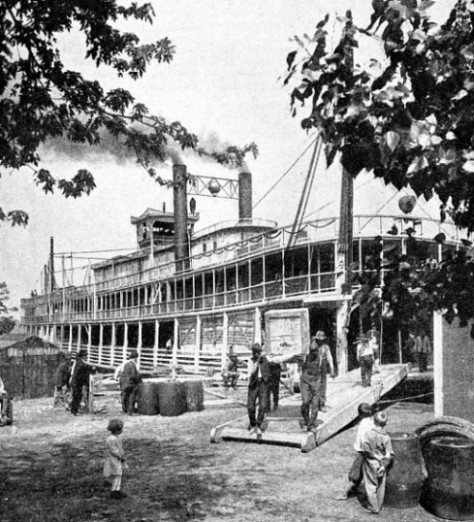

UNLOADING FREIGHT on the picturesque Illinois river-

A less sombre story of the war is told by Mark Twain, who recalled that a pilot once hid in his exposed pilot house while his colleague went ashore to “see the fight.” The steamer came under fire, and the unhappy pilot gave himself up for lost, hiding behind the pilot-

In 1870 the racing enthusiasm broke out again, and it was in that year that the historic run of the Natchez and the famous Robert E. Lee took place. The Robert E. Lee was the winner. She ran from New Orleans to Baton Rouge (Louisiana) in eight hours twenty-

The Robert E. Lee reached Vicksburg in twenty-

A chapter on old-

Riverside Entertainments

Thus there were born the famous “Show Boats”, which plied up and down the river and gave performances at outlying towns and overgrown villages on the banks. The coming of the cinema dealt an insidious blow at the show boats, as it has done at music halls and other places of entertainment elsewhere, but at least one show boat, the Mo, has survived into the nineteen-

Though most institutions suffer an eclipse after a period of greatness, they do not necessarily die out. Nothing really worth while dies out. The Mississippi steamboat of to-

a rival steamer over 1,200 miles of muddy water.

For the handling of freight in bulk, the river steamer on the Mississippi or its tributary streams is still an important factor. A big stern-

After the war of 1914-

On March 30, 1924, a huge self-

AT NEW ORLEANS, the John D. Grace has her gang-

Click here to see the photogravure supplement to this article.

You can read more on “American Shipping”, “The Great Lakes” and “The United States Navy” on this website.